Tohono Oʼodham facts for kids

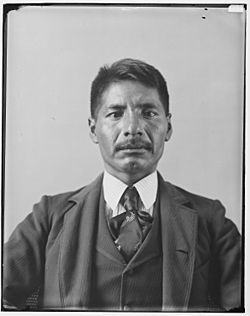

Jose Lewis, Tohono Oʼodham, 1907 or earlier, Smithsonian Institution

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Arizona) Mexico (Sonora) |

|

| Languages | |

| Oʼodham, English, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional, Catholic, Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Piman peoples |

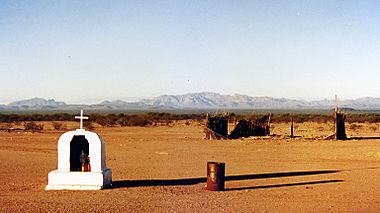

The Tohono Oʼodham are a Native American people. They live mainly in the Sonoran Desert, which is in the U.S. state of Arizona and the northern Mexican state of Sonora. The tribe is officially recognized in the United States as the Tohono Oʼodham Nation.

The Tohono Oʼodham Nation is a large reservation in southern Arizona. It covers parts of three counties: Pima, Pinal, and Maricopa. The reservation also reaches into the Mexican state of Sonora.

Contents

- What Does "Tohono Oʼodham" Mean?

- A Look at Tohono Oʼodham History

- Tohono Oʼodham Culture and Traditions

- The Tohono Oʼodham Nation Today

- Tohono Oʼodham Community Action (TOCA)

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s Visit to the Reservation

- Tohono Oʼodham Districts

- Notable Tohono Oʼodham People

- Images for kids

- See also

What Does "Tohono Oʼodham" Mean?

The Tohono Oʼodham tribal government and most of its people do not use the old name Papago. This name was given to them by European settlers. They call themselves Tohono Oʼodham, which means "desert people."

The Pima people, another tribe in the area, called them Ba꞉bawĭkoʼa. This means "eating tepary beans." Spanish settlers learned this name from the Pima and changed it to Pápago. Later, English speakers also used this term.

A Look at Tohono Oʼodham History

The Tohono Oʼodham people historically lived across a large area. This land is now southern Arizona and northern Mexico. It covers most of the Sonoran Desert. To the south, their land met the Seris and Opata peoples. To the east, they reached the San Miguel River valley. The Gila River was their northern border. To the west, their lands went to the Colorado River and the Gulf of California. They shared these borders with nearby tribes.

Living in the Sonoran Desert

Their lands have wide plains and tall mountains. Water is scarce, but it may have been more common before Europeans arrived. The people's cattle grazing and well drilling reduced stream flows. Natural springs gave water in some places. They also used tinajas, which are potholes in the mountains that collect rainwater.

Rainfall in the Sonoran Desert is very seasonal. Most rain falls in late summer monsoons. Monsoon storms are strong and cause floods. Other rain falls gently in winter. Snow is very rare, and winters have few days below freezing. The growing season is long, up to 264 days. Summer temperatures are extreme, reaching up to 49°C (120°F) for weeks.

The Tohono Oʼodham moved between summer and winter homes. They usually followed the water. They built summer homes on alluvial plains. Here, they directed summer rains onto their fields. They built some dikes and basins, like the Pima people to the north. But most streams were not steady enough for permanent canals. Winter villages were in the mountains. This gave them more reliable water and allowed men to hunt.

Early Conflicts and Encounters

Historically, the Oʼodham-speaking people were enemies of the nomadic Apache. This lasted from the late 1600s to the early 1900s. The Oʼodham were settled farmers. They knew the Apache would raid when food was scarce or hunting was bad.

As European settlers moved onto their lands, the Oʼodham and Apache found common interests. The Oʼodham word for Apache, 'enemy,' is ob. The relationship between the Oʼodham and Apache became very tense after 1871. In that year, 92 Oʼodham joined Mexicans and Anglo-Americans. They killed about 144 Apache in the Camp Grant massacre. Almost all the dead were women and children. The Oʼodham also captured 29 Apache children. They sold them into slavery in Mexico.

Not much is known about early Oʼodham history. What Europeans wrote often showed their own views. The first European exploration of Oʼodham lands was in the early 1530s. This was by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca from the Narváez expedition. Esteban the Moor, one of the four survivors, passed through these lands. He later led Fray Marcos de Niza to find the mythical Seven Cities of Gold. Esteban was killed by the Pima for disrespecting their customs. De Niza then ended his trip. De Niza wrote that the native cities were grander than Mexico City. This led to the Coronado expedition.

Some evidence suggests that before the late 1600s, the Oʼodham and Apache were friendly. They traded goods and married each other. However, Oʼodham oral history says that intermarriages happened because of raids. Women and children were often taken captive in raids and used as slaves. Often, women married into the tribe that held them captive. Both tribes brought "enemies" and their children into their cultures.

Mission San Xavier del Bac

The San Xavier District is home to Mission San Xavier del Bac. It is known as the "White Dove of the Desert." This is a popular tourist spot near Tucson. The mission was started in 1700 by Jesuit missionary and explorer Eusebio Kino. The first and current church buildings were built by Sobaipuri Oʼodham. The second building was built by Franciscan priests from 1783 to 1797. This is the oldest European building in Arizona. It is a great example of Spanish colonial design. It is one of many missions built by the Spanish in the Southwest.

Visitors sometimes think the desert people quickly accepted Catholicism. But Tohono Oʼodham villages resisted this for hundreds of years. In the 1660s and 1750s, two major rebellions happened. They were as big as the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Their armed resistance stopped the Spanish from moving further into Pimería Alta. The Spanish went back to what they called Pimería Baja. Because of this, the desert people kept their traditions mostly untouched for many generations.

Tohono Oʼodham Culture and Traditions

The Tohono Oʼodham share language and culture with the Akimel Oʼodham (People of the River). The Akimel Oʼodham were historically known as Pima. Their lands are south of Phoenix, along the lower Gila River. The Sobaipuri are ancestors to both the Tohono Oʼodham and the Akimel Oʼodham. They lived along the main rivers of southern Arizona. Ancient pictographs are on a rock wall near the Baboquivari Mountains.

Eric Winston wrote about the Oʼodham:

The Oʼodham were not a people in a political sense. Instead, their sense of belonging came from similar traditions and ways of life, language and related legends, and experiences shared in surviving in a beautiful but not entirely hospitable land.

There are debates about where the Oʼodham came from. Some believe the Hohokam, who left the Casa Grande Ruins, are their ancestors.

The Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library has materials from a Franciscan friar who worked with the Tohono Oʼodham. The Office of Ethnohistorical Research at the Arizona State Museum has translated old documents. These discuss Spanish relations with the Oʼodham in the 1600s and 1700s.

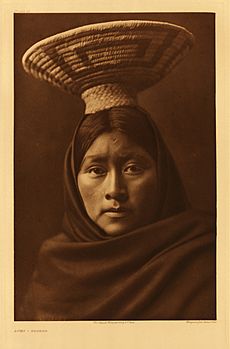

Oʼodham music and dance activities are not grand ceremonies like pow-wows. They wear muted white clay. Oʼodham songs use hard wood rasps and drumming on overturned baskets. These sounds are quiet and "swallowed by the desert floor." Dancing involves skipping and shuffling quietly in bare feet on dry dirt. The dust raised is believed to rise and help form rain clouds.

Family and Community Life

Society focused on the family, and everyone had specific jobs. Women prepared food and gathered most of it, though everyone helped. Older girls fetched water each morning. If there were no daughters, the wife did this. Women also wove baskets and made pottery, like ollas. Men did much of the farming and hunted. Older men hunted large animals like bighorn sheep. Younger men and boys hunted small animals.

Most communities had a medicine man, usually a male. Decisions were made by men together, with elders having a lot of say. Children played freely until age six. Then, they started learning their roles. Grandparents and older siblings were the main teachers, as parents were often busy.

Marriages were usually arranged by parents. If parents had died, older siblings arranged them. Villages were often closely related, so marriages were usually between different villages. Close relatives were not allowed to marry. A wife usually moved to her husband's village. But exceptions were made if the wife's village needed more help. Polygamy was allowed. Women had little choice in who they married. But they could leave a marriage if unhappy. They would then return to their village, and a new marriage would be arranged.

Society was very communal. There were few positions of authority. Hunters shared their catches with the whole village. Food and supplies were shared with those who needed them. If you were given things when you needed them, you were expected to repay the debt later.

The Oʼodham were only loosely connected across their lands. Loyalty was to the village, not the whole people. However, the Oʼodham generally got along well with neighbors. They often met with nearby villages. They even partnered with them against outside tribes during conflicts. Gatherings for races, trade, socializing, and gossip were common.

Gambling was a popular fun activity. Men played a game with sticks like dice. Women played a game tossing painted sticks. They bet small items like shells or beads, and valuables like blankets and mats. Betting also happened on races, which were the most important sport. Girls were often good runners from fetching water. Everyone needed to be able to run to escape danger. Day-long races were popular, with courses 16-24 km (10-15 mi) long. Women played a field hockey-like game called toka. It is still played and is a school sport on the modern reservation.

Different Tohono Oʼodham Groups

The Oʼodham shared a language root with the Pima. They could understand nearby tribes' languages. But these tribes were seen as distant cousins. Even within the Oʼodham, there were language and cultural differences. This meant the groups were only loosely connected. Different groups had different origin stories, language quirks, and appearances. Where a person lived was the best way to tell which group they belonged to. In the 1700s, when Europeans started to group tribes, there were probably at least six groups. The number of groups has changed depending on who wrote about them. Eric Winston's 1994 book lists seven groups:

- Himuris – They lived in modern Mexico, along the southern edge of Oʼodham lands. They were the first to meet Europeans.

- Hia C-eḍ – Divided into northern and southern groups, they lived along the western border. Their land was the hottest and driest, so they moved a lot. They were mostly hunter-gatherers.

- Hu:huhla – The oldest Oʼodham group, they lived east of the Hia C-eḍ. Other tribes called them "orphans." They lived like the Hia C-eḍ because their lands were also poor.

- Kohatk – They lived in the north and mixed with the Pima. They traded and married a lot with the Pimas.

- Koklolodi – They lived between the Himuris and Totokwan groups.

- Sobapuris – This eastern group lived between the San Pedro and Santa Cruz rivers. They were more like the Pima and lived in permanent settlements. Their lands had better water, so they could stay in one place all year. Their fertile lands were desired by European settlers, and they suffered most from colonization.

- Totokwan – Centered around Ge Aji Peak, they were the ceremonial center of the northern Oʼodham.

Diet and Food Traditions

The original Oʼodham diet included wild game, insects, and plants. They gathered many regional plants, such as: ironwood seed, honey mesquite, hog potato, and organ-pipe cactus fruit. They grew crops like white tepary beans, papago peas, and Spanish watermelons. They hunted pronghorn antelope, gathered hornworm larvae, and trapped pack rats for meat. They steamed plants in pits and roasted meat over open fires.

Saguaro cactus fruit was a very important food. The Tohono Oʼodham use long sticks to pick the fruits. They make them into jams, syrups, and a special wine for ceremonies. The seeds are also edible and were made into porridge. The harvest starts in June. Villages would travel to the saguaro stands for the harvest. A tool called a kuibit is made from two saguaro ribs, about 6 meters (20 ft) long. They boil the fresh fruit for hours to make a thick syrup, as fresh fruit spoils quickly. 4 kg (9 lb) of fruit makes about 1 liter (1 US quart) of syrup. A lot of fruit was harvested; for example, in 1929, 600 families harvested 45,000 kg (99,000 lb).

At the end of the harvest, each family gave a small amount of syrup to a shared stock. The medicine man would ferment this. This was for rainmaking celebrations. They told stories, danced a lot, and sang songs. Each man drank some of the saguaro wine. The resulting feeling was seen as holy, and any dreams it brought were important. This was the only time the Oʼodham drank alcohol during the year.

Ak cin, meaning "mouth of the wash," is a farming method. Farmers watched for storm clouds. When clouds appeared, it meant heavy rain was coming. Farmers quickly prepared their fields for planting as the rain flooded their lands. This farming was mostly used during summer monsoons.

Traditional tribal foods were a mix of wild plants and animals, and cultivated crops. From nature, they ate rabbit, sap and flour from mesquite trees (flour from crushed pods), cholla cactus, and acorns. For farming, they grew corn, squash, and tepary beans.

Traditions in Modern Times

When more Anglo-American settlers moved into Arizona, they started to pressure the people's traditional ways. Unlike many tribes, the Tohono Oʼodham never signed a treaty with the U.S. government. But they faced challenges like other Native American nations.

Under the Dawes Act of 1888, Oʼodham communal lands were divided among families. Some "extra" land was sold to non-Native Americans. Different religious groups came into the area. Presbyterian missionaries built schools and missions. They competed with Roman Catholics and Mormons to convert the Oʼodham.

Large farms started the cotton industry. Many Oʼodham worked there as farm laborers. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the U.S. government made Native American children attend Indian boarding schools. They were forced to speak English, practice Christianity, and give up their tribal cultures. The government wanted to make them part of mainstream American society.

The current tribal government was set up in the 1930s under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. It shows years of business, missionary, and government influence. The government encouraged tribes to restart their governments. But it approved models based on the U.S. election system. The goal was to make Native Americans into "real" Americans. But boarding schools usually only taught skills for low-level jobs in rural areas. "Assimilation" was the official policy, but full participation was not the goal. Boarding school students were meant to work as laborers in a segregated society, not as leaders.

The Tohono Oʼodham have kept many traditions into the 21st century. They still speak their language. However, since the late 1900s, U.S. mass culture has influenced and sometimes changed Oʼodham traditions. Their children adopt new trends in technology and other practices.

Keeping Culture Alive Today

The cultural resources of the Tohono Oʼodham are at risk, especially the language. But they are stronger than those of many other Native American groups.

Every February, the nation holds the annual Sells Rodeo and Parade in its capital. The Sells District rodeo has been an annual event since 1938. It celebrates traditional skills of riding and managing cattle.

In art, Michael Chiago and the late Leonard Chana are well-known. They created paintings and drawings of traditional Oʼodham activities and scenes. Chiago has shown his work at the Heard Museum. He has also created cover art for Arizona Highways magazine and University of Arizona Press books. Chana illustrated books by Tucson writer Byrd Baylor. He also made murals for Tohono Oʼodham Nation buildings.

In 2004, the Heard Museum gave Danny Lopez its first heritage award. This recognized his lifelong work to keep the desert people's way of life strong. At the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), the Tohono O'odham were part of the first exhibition. Lopez blessed the exhibit.

The Tucson Indian School

Tohono Oʼodham children had to attend Indian boarding schools. These schools aimed to teach them English and make them fit into mainstream European-American ways. According to historian David Leighton, Tohono Oʼodham children attended the Tucson Indian School. This boarding school started in 1886. T.C. Kirkwood, a superintendent for the Presbyterian Church, asked the Tucson Common Council for land. The Council gave the Board of Home Missions a 99-year lease for $1 a year. The Board bought 17 hectares (42 acres) of land from Sam Hughes.

The new school opened in 1888 with 54 boys and girls. At this semi-religious boarding school, boys learned trades like carpentry and farming. Girls learned sewing and other household skills. By 1890, more buildings were finished, but the school was still too small. Students had to be turned away. To raise money, the superintendent made a deal with Tucson to grade and maintain streets. The school was officially called the Tucson Indian Training School. But "any person of either sex, regardless of race or color" could be admitted if they showed "promise of development into a Christian leader or citizen."

In 1903, Jose Xavier Pablo graduated from the school. He later became a leader in the Tohono Oʼodham Nation. Three years later, the school bought the land they were leasing and sold it for a good profit. In 1907, they bought land east of the Santa Cruz River. They built a new school there, which opened in 1908. It had its own post office, called the Escuela Post Office. This name was sometimes used instead of Tucson Indian School.

By the mid-1930s, the Tucson Indian School covered 65 hectares (160 acres). It had 9 buildings and could teach 130 students. In 1940, about 18 different tribes made up the student population. As ideas about Native American education changed, the government started to support schools where children lived with their families. By August 1953, it had no grades lower than 7th grade. In 1960, the school closed. The site is now Santa Cruz Plaza, southwest of Pueblo Magnet High School.

The Tohono Oʼodham Nation Today

The Tohono Oʼodham Nation in the United States has a reservation. It covers part of their original Sonoran desert lands. It is divided into eleven districts. The land is in three counties in Arizona: Pima, Pinal, and Maricopa. The reservation is 11,534 square kilometers (4,453 sq mi). This makes it the third-largest Indian reservation in the United States. In 2000, 10,787 people lived on the reservation. The tribe's office counts 25,000 members, with 20,000 living on its Arizona reservation lands.

How the Nation is Governed

The nation is led by a tribal council and a chairperson. They are elected by adult members of the nation. Their constitution has a special system for elections. This system makes sure that the rights of small Oʼodham communities are protected. It also protects the interests of larger communities and families. The current chairman is Ned Norris Jr..

Tohono Oʼodham Lands

Like other tribes, the Tohono Oʼodham faced pressure for their land. This came from American ranchers, settlers, and railroads. Land records were poor, and many members did not leave written wills for their land. John F. Trudell, a U.S. attorney general assistant, recorded an Oʼodham man saying, "I do not know anything about a land grant. The Mexicans never had any land to give us. From the earliest times our fathers have owned land which was given to them by the Earth's prophet."

Because the Oʼodham lived on public lands or had no ownership papers, their lands were threatened by white cattle herders in the 1880s. However, they used their history of working with the government in the Apache Wars to get land rights. Today, Oʼodham lands include several reservations:

- The main reservation, Tohono Oʼodham Indian Reservation. It is 11,243 square kilometers (4,341 sq mi). In 2000, it had 8,376 people.

- The San Xavier Indian Reservation. It is 288.9 square kilometers (111.5 sq mi) and has 2,053 people. It is in Pima County, near Tucson.

- The San Lucy District. It has seven small pieces of land near Gila Bend. Its total area is 1.9 square kilometers (0.7 sq mi), with 304 people.

- The Florence Village District. It is southwest of Florence. It is one piece of land, 0.1 square kilometers (0.04 sq mi) in area, with 54 people.

Tohono Oʼodham Community Action (TOCA)

The Tohono Oʼodham Community Action (TOCA) was started in 1996. It was founded by Terrol Dew Johnson and Tristan Reader. Their goal was to bring back lost tribal traditions. TOCA is in Sells, Arizona. It began as a community garden and offered basket weaving classes. Now, TOCA has two farms, a restaurant, and an art gallery.

One reason TOCA was created was that the tribe faced many challenges. They were becoming very dependent on welfare and food stamps. The Tohono Oʼodham people had one of the lowest incomes of any Native American reservation. 65% of members lived below the poverty line, and 70% were unemployed. Crime among young people increased due to gangs, and over 50% of high school students dropped out. The homicide rate was three times the national average.

In 2009, TOCA opened its restaurant, Desert Rain Café. The cafe's goal was to bring traditional tribal foods back to the community. This helps fight the rise of Type 2 diabetes. The restaurant uses traditional ingredients in every dish. These include mesquite meal, prickly pear, or agave syrup. For crops like tepary beans or squash, the café uses its own farms. This provides fresh meals to customers. Some dishes include Mesquite Oatmeal Cookies, Short Rib Stew, Brown Tepary Bean Quesadillas, or pico de gallo. The restaurant serves over 100,000 meals each year.

Basket weaving was a very important cultural practice. It was used in rain ceremonies that lasted four days and nights. Baskets were also used daily to hold or prepare foods. When TOCA started, Johnson held weekly classes for artists. Making a basket could take up to a year. This long process is because the fibers must be harvested and prepared. Also, a design that shows the history of the Tohono Oʼodham nation must be created. Materials for baskets include native grasses like Yucca grass and devil's claw plant, an awl, and a knife.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Visit to the Reservation

On April 2, 2017, historian David Leighton wrote in the Arizona Daily Star newspaper about Martin Luther King Jr.'s first visit to an Indian reservation. This was the Tohono Oʼodham Indian Reservation.

On September 20, 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. flew to Tucson from Los Angeles. He was there to give a talk at the Sunday Evening Forum. That night, he gave a speech called "A Great Time To Be Alive" at the University of Arizona auditorium. After the talk, a reception was held for King. He met Rev. Casper Glenn, pastor of the multiracial Southside Presbyterian Church. King was very interested in this church and arranged to visit it the next day.

The next morning, Glenn picked up King in his car. He drove him to the Southside Presbyterian Church. There, Glenn showed King photos of the diverse church members. Most were part of the Tohono Oʼodham tribal group. Glenn remembered that King said he had never been on an Indian reservation. He also said he had never had a chance to get to know any Native Americans. King then asked to be driven to the nearby reservation.

The two men traveled to Sells, on what was then called the Papago Indian Reservation. When they arrived at the tribal council office, the tribal leaders were surprised and honored to see King. King was eager to talk to them. "He was fascinated by everything that they shared with him," Glenn said.

The ministers then went to the local Presbyterian church in Sells. Its members had recently built it with funds from the national Presbyterian church. King met Pastor Towsand, who was excited. On the way back to Tucson, "King expressed his appreciation of having the opportunity to meet the Indians," Glenn recalled.

Tohono Oʼodham Districts

- Gu Achi District

- Pisinemo District

- Sif Oidak District

- Sells District

- Baboquivari District

- Hickiwan District

- San Lucy District

- Gu Vo District

- Chukut Kuk District

- San Xavier District

- Schuk Toak District

Notable Tohono Oʼodham People

- Annie Antone, basket weaver

- Terrol Dew Johnson, basket weaver and food advocate

- Augustine Lopez, Tohono Oʼodham nation chairman

- Ponka-We Victors, Kansas state legislator

- Ofelia Zepeda, linguist, poet, writer

- Juan Dolores, early Tohono Oʼodham linguist

- Maria Chona, basket weaver

- Raul Mendoza, basketball coach

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo pápago para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo pápago para niños