Venezuelan independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Venezuelan Independence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish American wars of independence | |||||||

Signing of the Declaration of Independence by Juan Lovera. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

The Venezuelan independence was a big step for Venezuela to break free from the Spanish Empire. It meant that Venezuela would no longer be ruled by a king, but would become a republic with its own government.

This fight for independence led to a war called the Venezuelan War of Independence. In this war, the "Patriots" (who wanted independence) fought against the "Royalists" (who wanted to stay with Spain).

On July 5, 1811, Venezuela signed its Declaration of Independence. This day is now celebrated as Venezuela's national day. The "Patriotic Society", with leaders like Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda, played a key role in pushing for this separation from Spain.

Venezuelan historians divide the period between 1810 and 1830 into four main parts:

- First Republic (1810 -1812)

- Second Republic (1813 -1814)

- Third Republic (1817-1819)

- Gran Colombia (1819 -1830)

Contents

Why Did Venezuela Seek Independence?

Many things led to Venezuela wanting independence.

- Creole Power: The "Creoles" (people of Spanish descent born in America) had money and social status, but no real political power. They wanted more control.

- Unhappy People: Many people were unhappy with how the Spanish government was managing things. Taxes were also going up.

- New Ideas: Ideas from the Enlightenment and Encyclopedism spread, making people think about freedom and self-governance.

- Other Revolutions: The success of the Declaration of Independence of the United States, the French Revolution, and the Haitian Revolution inspired Venezuelans.

- Spanish King: The rule of Joseph I of Spain (Napoleon's brother) in Spain also caused problems and weakened Spain's control over its colonies.

Early Attempts at Freedom

Venezuela saw its first tries for independence in the late 1700s.

- Miranda's Expeditions (1806): General Francisco de Miranda tried twice in 1806 to invade Venezuela from Haiti. He brought an armed group, but his attempts failed because people didn't support him and religious leaders spoke against him.

- Mantuanos' Plot (1808): In 1808, a group called the "Mantuanos" (the most powerful social group in Caracas) tried to form their own governing board. This happened because Napoleon had invaded Spain, causing confusion about who was in charge.

The First Republic (1810-1812)

The Revolution of April 19, 1810

The First Republic began on April 19, 1810. On this day, the Supreme Junta of Caracas peacefully took over from the Spanish authorities.

The local council (called a cabildo) in Caracas forced the Spanish Captain General, Vicente Emparan, to resign. The cabildo then formed itself into the "Supreme Conservative Junta of the Rights of Ferdinand VII." This new junta wanted to keep the king's rights, but govern Venezuela themselves.

The Caracas Junta asked other provinces in Venezuela to join their movement. Many agreed, including Cumaná, Barcelona, Margarita, Barinas, Mérida, and Trujillo.

However, some provinces like Guayana, Coro, and Maracaibo stayed loyal to Spain.

Forming the Supreme Congress

The Supreme Junta of Caracas realized it couldn't just be "conservative" and needed to decide Venezuela's future. So, they called for elections to create a new Congress. This Congress would then take over power and decide what would happen next.

The elections happened in October and November 1810. Only free men over 25 (or 21 if married) who owned a certain amount of property could vote. Women, slaves, and poor people could not vote.

Forty-four deputies were elected to the Congress. Caracas had the most representatives with 24.

The Supreme Congress of Venezuela officially started on March 2, 1811. The Supreme Junta of Caracas then handed over its powers on March 5, 1811.

The Patriotic Society's Influence

A group called the "Sociedad de Agricultura y Economía" quickly became a strong voice for breaking away from Spain. Important members included José Félix Ribas, Francisco José Ribas, and Vicente Salias. They discussed many topics, from money to military matters. This group grew to 600 members in Caracas alone and had branches in other cities.

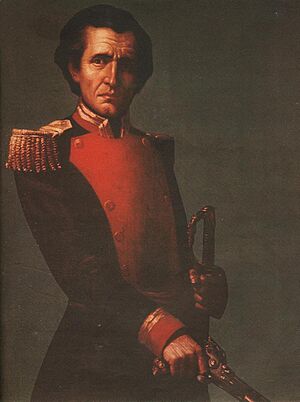

When Generalissimo Francisco de Miranda and young Simón Bolívar joined, the society became even more revolutionary. They openly criticized Spanish rule, spread ideas of independence, and pushed the Congress to declare independence.

Declaring Independence

Inside the Supreme Congress, there were two main groups:

- Separatists: Those who wanted Venezuela to be independent.

- Fidelists: Those who wanted to stay loyal to King Ferdinand VII of Spain.

As the Congress met, more and more deputies started to support independence. They gave strong speeches and used historical facts to argue their case.

On July 2, 1811, a proposal for independence was made. The debate began on July 3, and on July 5, the vote was taken. Independence was approved with 40 votes in favor! The president of the Congress, Juan Antonio Rodriguez, immediately announced that "The absolute Independence of Venezuela [was] solemnly declared."

After the vote, Francisco de Miranda and other members of the Patriotic Society led a large crowd through the streets of Caracas, cheering for independence and freedom.

The deputies decided to call the new country the "Confederación Americana de Venezuela." They also chose a committee to design a flag and write a constitution. Juan Germán Roscio and Francisco Isnardi wrote the official document, the "Act of Declaration of Independence," which was approved on July 7.

On July 13, 1811, the new flag of Venezuela was approved. It was based on a design by Francisco de Miranda from 1806. This flag was proudly raised for the first time in a public ceremony on July 14.

The Congress approved the Federal Constitution of the States of Venezuela of 1811 on December 21, 1811. Later, the Congress moved to Valencia, making it the new Federal City.

The Valencia Uprising

Just six days after the Declaration of Independence, on July 11, 1811, two uprisings happened. One in Caracas was quickly stopped. The other was a bigger rebellion in Valencia. The Mantuanos, who didn't like the Patriots, sent the Marquis del Toro to stop the Valencia uprising, but he was defeated.

Then, Francisco de Miranda, at 61 years old, was made Commander in Chief of the Army. He marched to Valencia with his troops. The fighting in the city was tough, but on July 23, the Patriots took control of Valencia.

The First Republic Falls (1812)

On March 26, 1812, a terrible earthquake hit Caracas, causing huge damage and killing about 20,000 people. This weakened the new republic.

That same year, Simón Bolívar lost control of Puerto Cabello. Then, Francisco de Miranda surrendered in San Mateo to the Royalist leader Juan Domingo de Monteverde. Miranda signed an agreement: the Patriots would give up their weapons, and the Royalists would respect people and their belongings.

However, when Miranda was about to leave from La Guaira, he was arrested by his former comrades, including young Simón Bolívar. They accused him of misusing public money and handed him over to the Royalists. Miranda was imprisoned in Puerto Cabello, then moved to Puerto Rico, and finally to a prison in Cádiz, Spain, where he died in 1816.

The Second Republic (1813-1814)

The Second Republic lasted from August 1813 to December 1814. This period is often called the "War to the Death" because of its harshness.

After the First Republic fell, many Patriot leaders went into exile. Bolívar wrote the Cartagena Manifesto in December 1812. In this important document, he explained why the First Republic failed and what the future might hold for the new countries. He pointed out several reasons for the failure:

- Weak Government: The use of a federal system was too weak for the time.

- Poor Money Management: Public money was not managed well.

- Natural Disaster: The 1812 earthquake in Caracas caused great destruction.

- No Permanent Army: It was hard to keep a strong, permanent army.

- Church Influence: The Catholic Church had a negative influence on the independence movement.

On the Royalist side, Domingo de Monteverde became too proud of his success. He refused to give power to General Fernando Mijares, who was appointed Captain General by Spain. Monteverde also broke his agreement with Miranda and began to punish the Patriots. He planned to invade the Republic of New Granada, which had declared its independence.

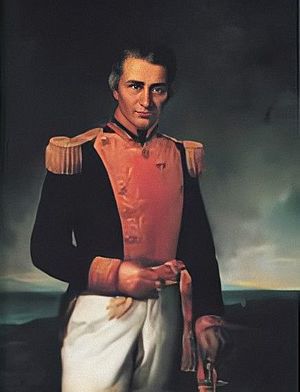

Knowing Monteverde's plans, Bolívar joined the New Granada army and got their support. This allowed him to start the military operations known as the Admirable Campaign.

The Admirable Campaign

Bolívar's forces quickly moved through New Granada. On January 8, 1813, he took the city of Ocaña. On February 16, he headed for Cúcuta, where Royalist forces were present. On February 28, the Battle of Cúcuta took place, which freed the city.

In the first half of 1813, the Royalist resistance collapsed. Monteverde was defeated and wounded. He retreated to Puerto Cabello, where his own soldiers removed him from command.

The war continued with two main campaigns:

- Eastern Campaign: Led by General Santiago Mariño in the east.

- Admirable Campaign: Led by Bolívar in the west.

Mariño liberated Cumaná on August 3, 1813. Bolívar entered Caracas on August 6.

Bolívar's return to Caracas marked the start of the Second Republic. From Caracas, Bolívar declared "War to the Death" against the Spanish. The city of Caracas gave Bolívar the title of "El Libertador" ("The Liberator") and "General in Chief of the Republican Army." The next year, he was named Supreme Chief.

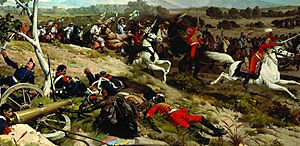

The military situation became difficult with the rise of José Tomás Boves. Boves was an Asturian who organized an army of black and mixed-race people to fight for the Royalists. Some historians believe Boves used the social anger of these groups against the Venezuelan whites who led the independence movement.

Battles in the Aragua Valleys

From February 1814, many battles took place in the Aragua Valleys, from Lake Valencia to San Mateo. In the San Mateo hacienda, owned by Simón Bolívar, there was a gunpowder storage area. Captain Antonio Ricaurte and 50 soldiers were guarding it. During a Royalist attack, Francisco Tomás Morales's forces tried to capture the gunpowder. Ricaurte, seeing the enemy about to take it, set fire to the gunpowder, blowing himself and the Royalist soldiers up on March 25, 1814. This heroic act prevented the Royalists from getting the gunpowder. Bolívar used the confusion to counterattack and retake the area.

In 1814, there were many bloody battles and attacks on civilians by both sides. The people of Caracas had to flee to the east because Boves was approaching. Historians mark the Battle of Maturín on December 11, 1814, as the end of the Second Republic.

After the Admirable Campaign, Bolívar continued fighting the Spanish. He sent troops to different areas to deal with Royalist forces. For example, he sent Tomás Montilla to the plains of Calabozo to face Boves, and Vicente Campo Elías to calm down the Valles del Tuy where a rebellion had started.

Bolívar also went to Valencia, where he gathered troops. He divided them into three groups to attack Puerto Cabello and other areas. His forces won battles in Bárbula and Trincheras, forcing Monteverde to retreat.

Bolívar learned a big lesson from the defeat of the First Republic: unity was key to winning the revolution. He wrote in his famous Cartagena Manifesto, "Our division and not the Spanish arms turned us to slavery."

He also realized that the first two republics failed because they only focused on helping rich landowners, not the slaves or poor farmers who made up most of the independence army.

The "War to the Death" Decree

Colonel Atanasio Girardot joined Simón Bolívar in the Admirable Campaign. He fought bravely and helped take the cities of Trujillo and Mérida. As Bolívar moved towards Caracas, Girardot was in charge of the rear guard. On September 30, 1813, during the Battle of Bárbula, Girardot was killed by a rifle bullet while trying to place the national flag on a captured height.

The decree of War to the Death was a declaration made by Simón Bolívar on June 15, 1813, in Trujillo. Bolívar issued this decree because Spanish soldiers had committed many crimes and massacres against Patriots after the First Republic fell. The goal was to make the Venezuelan war look like a fight between two countries (Venezuela and Spain), not just a civil war within a colony.

The decree stated that all Spanish people who did not actively support independence would be killed. However, all Americans would be pardoned, even if they had passively helped the Spanish. Both sides practiced this "War to the Death." Many people were killed by both the Spanish and the Patriots. For example, in February 1814, Spanish prisoners were executed in Caracas and La Guaira on Bolívar's orders.

This declaration lasted until November 26, 1820. On that date, the Spanish general Pablo Morillo met with Bolívar to agree that the war would be fought as a regular war between civilized nations.

The Battle of Araure

After the Admirable Campaign, the Patriots were fighting Royalists in central-western Venezuela. In one battle near Barquisimeto on November 10, the Patriots were defeated due to poor coordination. Bolívar was very upset. He ordered the remaining soldiers from three battalions ("Aragua," "Caracas," and "Agricultores") to form a single new battalion that would have no name.

By mid-1813, most of Venezuela was controlled by the Patriots, except for Guayana and Maracaibo. In September 1813, the Royalists received more soldiers from Spain, leading to more fighting across the country. The Patriots continued to win battles until the end of 1813. One important victory was the Battle of Araure, where Simón Bolívar defeated José Ceballos.

On December 3, 1813, Bolívar learned that Royalist forces (3,500 men) led by Brigadier José Ceballos had joined with José Yáñez in Araure. Bolívar ordered his forces to gather in Aguablanca. On December 5, the Patriots marched to Araure and set up camp near the town, facing the Royalists. The Royalists had strong positions, protected by woods and a small lake, and had 10 cannons.

Colonel Florencio Jiménez was put in charge of the "Batallón sin nombre" ("Battalion without a name"). To make things worse, they were given spears instead of rifles. This battalion became a joke in the Patriot army. However, they got their chance to prove themselves on December 5, 1813, in Araure. In this battle, the nameless battalion played a crucial role. Armed only with spears, they attacked the "Numancia" battalion, one of the best Spanish units, and broke their lines, forcing them to retreat.

On December 5, the battle began. Bolívar's forces attacked, and after fierce fighting, they broke through the enemy's front line, causing great confusion and leading to a Patriot victory. Bolívar himself led the pursuit of the defeated Royalists. The battle lasted about six hours. The Royalists had more soldiers than the Patriots. The Patriots captured 200 prisoners, four flags, and many cannons. Over 500 Royalist horsemen were killed.

The next day, Bolívar praised the nameless battalion, saying:

"Your courage has won yesterday on the battlefield, a name for your corps, and even in the midst of the fire, when I saw you triumphant, I proclaimed it of the Victor Battalion of Araure. You have taken from the enemy flags that at one time were victorious; the famous invincible call of Numancia has been won."

The Fall of the Second Republic

The Battle of Úrica was a key military action fought on December 5, 1814, in Anzoátegui. In this battle, the Patriot field marshal José Félix Ribas faced José Tomás Boves, who was known for his extreme cruelty. Boves led the Royalists in the Battle of Úrica, and he died in this fight. Ribas had 2,000 men, including leaders like José Tadeo Monagas and Pedro Zaraza.

Ribas's forces marched through the night to reach Úrica at dawn, facing the Royalists. Boves started the hostilities, but the Patriots managed to push back his attack. This early success allowed Ribas to line up his men and charge the Royalists. When Boves realized his column was surrounded, he rushed into the fight and was killed. However, the rest of the Royalist forces charged and surrounded the Patriot line, winning the battle. Both sides suffered many casualties.

The Third Republic (1817-1819)

The Third Republic lasted from 1817 until December 1819, when Simón Bolívar created the Gran Colombia republic. After the Second Republic fell, Patriot leaders found safety on Caribbean islands like Jamaica, Trinidad, Haiti, and Curacao. From there, with help from these countries (especially Haiti), they restarted their fight.

Bolívar returned to New Granada, hoping to repeat his Admirable Campaign, but his supporters disagreed. Feeling misunderstood, he went into exile in Jamaica on May 9, 1815. He wanted to get support from the English-speaking world for Spanish-American independence. He stayed in Kingston from May to December 1815, thinking deeply about the future of the American continent.

The Letter from Jamaica is a famous text written by Simón Bolívar on September 6, 1815, in Kingston. In it, he explained why the Second Republic failed. Although addressed to Henry Cullen, its main goal was to get Great Britain to help with American independence.

The Situation in Margarita

Around 1815, General Juan Bautista Arismendi was the temporary Governor of Margarita Island. The Spanish were harassing Patriots across the country. For months, Arismendi and his family lived under Spanish watch. In September 1815, Arismendi was ordered to be arrested, but he escaped and hid. On September 24, his pregnant wife, Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi, was taken hostage to force her husband to surrender. She was held in a dungeon in the Castillo Santa Rosa.

General Arismendi's military actions led him to capture several Spanish leaders. The Royalist chief Joaquín Urreiztieta offered to exchange these prisoners for Arismendi's wife. Arismendi refused, saying, "Tell the Spanish chief that without a country I don't want a wife." After this, Luisa's captivity became even harder.

On January 26, 1816, Luisa gave birth to a baby girl who died at birth due to the harsh conditions in the dungeon.

She was kept isolated and without news of her family. However, Patriot victories in Margarita (led by Arismendi) and in Apure (led by General José Antonio Páez) led the Spanish to decide to transfer Luisa Cáceres de Arismendi to Cadiz, Spain. She was taken to prison in La Guaira on November 24, 1816, and sailed on December 3. At sea, her ship was attacked, and she ended up on the island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Unable to return to Venezuela, Luisa finally reached Cadiz. She refused to sign a document declaring loyalty to the King of Spain and denying her husband's Patriot beliefs. She bravely stated that her husband's duty was to serve his country and fight for its freedom.

The Expedition of Los Cayos

The Expedition of Los Cayos de San Luis was a name given to two invasions by Simón Bolívar from Haiti in late 1815 and 1816. His goal was to free Venezuela from Spanish forces.

After leaving Haiti, Bolívar's fleet sailed towards Venezuela. On April 19, 1816, they reached Vieques Island near Puerto Rico. On May 2, before reaching Margarita, they fought the naval battle of Los Frailes, where Luis Brión's squadron won and captured two Spanish ships. On May 3, 1816, they landed on Margarita. On May 6, an assembly led by General Juan Bautista Arismendi confirmed Bolívar's special powers.

After this, Bolívar's forces went to Carúpano, where they landed and declared the end of slavery. They continued to Ocumare de la Costa and reached Maracay, but had to retreat due to attacks by Francisco Tomás Morales. They left some supplies and about half their soldiers, who, under McGregor, began a retreat by land through the Valles de Aragua del Este, known as the "Retreat of the Six Hundred."

Bolívar returned to Haiti, organized a new expedition, and landed in Juan Griego on December 28, 1816, and in Barcelona on December 31. He set up his headquarters there and planned to attack Caracas. However, after some problems, he changed his plan and moved to Guayana to lead operations against the Royalists there.

Despite the difficulties, the Expedition of Los Cayos was very important. It allowed Santiago Mariño, Manuel Piar, and later José Francisco Bermúdez to start freeing eastern Venezuela. It also allowed Gregor MacGregor and Carlos Soublette to enter the mainland and pave the way for the Republic's final victory.

Landing on the Coasts

The Retreat of the Six Hundred was a long journey of hundreds of kilometers through enemy territory. Patriots fought with few weapons and ammunition during the Expedition of Los Cayos in 1816. After the retreat, these 600 men joined the eastern Patriot forces under Manuel Piar with renewed confidence.

Venezuelan Patriots had landed on the coast of Aragua and moved inland to Maracay. But an attack by Francisco Tomás Morales pushed them back to the beaches. In the chaos, the Patriots quickly boarded ships, leaving most of their supplies and 600 men under Gregor MacGregor on the beach.

Later, General Santiago Mariño, with José Francisco Bermúdez, marched on Irapa, where they destroyed a Spanish garrison. They then reached Carúpano after the Royalists left the area. On September 15, Mariño established himself in Cariaco and, with support from Juan Bautista Arismendi's fleet, began operations against Cumaná.

After some successes in Maturín, and knowing about Mariño's advance on Cumaná and MacGregor's retreat, General Piar arrived at Chivacoa with 700 men. He then moved to Ortiz to threaten Cumaná and connect with Mariño and MacGregor.

After several fights, Piar moved to the province of Guayana, where General Manuel Cedeño was operating. They joined forces and advanced against the city of Angostura. Bolívar established his headquarters in Barcelona and planned an attack on Caracas. However, a defeat in the Battle of Clarines on January 9, 1817, forced Bolívar to return to Barcelona. Due to political and strategic problems, Bolívar stopped the "Barcelona Campaign" and left for Guayana to join Manuel Piar.

The Guayana Campaign

The Guayana Campaign of 1816-1817 was the second campaign by Venezuelan Patriots in the Guayana region during the War of Independence. The first campaign in 1811-1812 had failed.

This campaign was a great success for the Patriots, led by Manuel Piar. After several battles, they managed to drive all the Royalists out of the region. This gave the Patriots control of an area rich in natural resources and with good access to communication routes, which became a base for launching campaigns into other parts of the country.

The Llanos and Key Battles

With José Antonio Páez in the Llanos (plains) and Manuel Piar in Guayana, the Patriots gained strength. San Félix and Angostura were freed in 1818. This gave the Patriots a rich territory with access to the sea through the Orinoco river. José Antonio Páez met with Simón Bolívar, who came from Angostura to join the Apure army in a campaign against Guárico.

General Páez recognized Bolívar's authority. On February 12, 1818, in the Taking of Las Flecheras, the "llanero" lancers crossed the Apure River on their horses, surprising the Royalists and capturing their boats. Then, in the Battle of Calabozo, Bolívar defeated Pablo Morillo. Páez, leading the vanguard, pursued the Spanish and defeated them again in Uriosa on February 15, 1818.

The Battle of Las Queseras del Medio was an important military action on April 2. Páez's cavalry attacked their pursuers, destroying the Royalist cavalry. Las Queseras was the greatest victory of General Páez's military career. Bolívar honored him with the Order of the Liberator the next day.

After Bolívar promoted Páez to major general, they fought the Apure campaign together against Morillo's troops. Once that campaign ended with Morillo's retreat, Bolívar began the Campaign for the Liberation of New Granada. Páez was given the important task of protecting Bolívar's forces and watching Morillo's movements.

The Congress of Angostura

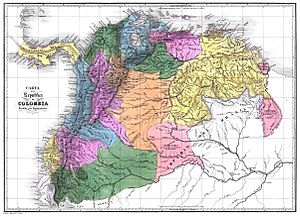

On February 15, 1819, Bolívar opened the Congress of Angostura and gave his famous Discurso de Angostura (Angostura Speech). This Congress brought together representatives from Venezuela, New Granada (now Colombia), and Quito (now Ecuador). Key decisions made were:

- New Granada was renamed Cundinamarca, and its capital, Santa Fe, was renamed Bogotá. Quito's capital would be Quito. Venezuela's capital would be Caracas. The capital of the new larger country, Gran Colombia, would be Bogotá.

- The "Republic of Colombia" was created, to be led by a President and a Vice-President. (This country is now historically known as Gran Colombia).

- The governors of the three regions would also be called vice-presidents.

- Simón Bolívar was elected President of the Republic, and Francisco de Paula Santander was elected Vice President. In August, Bolívar left to continue his liberation efforts in Ecuador and Peru, leaving Santander in charge of the presidency.

- Bolívar was given the title of "Libertador" (Liberator), and his portrait would be displayed in Congress with the motto "Bolívar, Liberator of Great Colombia and Father of the Homeland."

On December 17, 1819, Venezuela and New Granada officially united, and the Republic of Colombia was born. This marked the end of the Third Republic.

By this time, the Spanish only controlled the northern central part of Venezuela, including Caracas, Coro, Mérida, Cumaná, Barcelona, and Maracaibo.

The Armistice of Santa Ana

After six years of war, the Spanish general Pablo Morillo agreed to meet with Bolívar in 1820. After New Granada was freed and the Republic of Colombia was created, Bolívar and the Spanish general Pablo Morillo signed an Armistice and a Treaty of Regularization of the War on November 26, 1820. Marshal Antonio José de Sucre wrote this Armistice and War Regularization Treaty, which Bolívar called "the most beautiful monument of kindness applied to war."

Morillo had received orders from Spain to stop fighting with Bolívar. He told Bolívar about the Spanish army's ceasefire and invited him to discuss an agreement to make the war more humane. Representatives from both sides met, and then Bolívar and Morillo met on November 25. On that day, the Armistice between the Republic of Colombia and Spain was signed. This agreement stopped all military actions on land and sea in Venezuela and kept both armies in their current positions.

The documents written by Antonio José de Sucre were very important. They temporarily stopped the fighting between Patriots and Royalists and ended the "War to the Death" that began in 1813. The Armistice of Santa Ana gave Bolívar time to plan his strategy for the Battle of Carabobo, which would secure Venezuela's independence. This treaty was a milestone in international law because Sucre set a new standard for how defeated enemies should be treated in war. He became a pioneer of human rights.

The Armistice Treaty aimed to stop fighting to allow for peace talks. It was signed for six months and required both armies to stay in their positions. The treaty stated:

"Whereby war shall henceforth be waged between Spain and Colombia as it is waged by civilized peoples."

Pablo Morillo later shared in his memories that when he returned to Spain after meeting Bolívar and signing the Armistice, the King of Spain asked him:

"Explain to me how it is that you, who triumphed against the French, against the troops of Napoleon Bonaparte, arrive here defeated by savages."

Morillo replied:

"Your Majesty, if you give me a Paez and 100,000 plainsmen from Apure whom you call Savages, I will lay the whole of Europe at your feet."

The Battle of Carabobo

When the armistice ended on April 28, 1821, both sides began to move their forces. The Spanish had their troops spread out, hoping to defeat the Patriot groups one by one. The Patriots, led by Bolívar, needed to bring their troops together for one big, decisive battle.

The Patriot troops gathered in San Carlos. Bolívar's army, Páez's army, and Colonel Cruz Carrillo's division all met there. The army from the east, led by José Francisco Bermúdez, created a distraction by advancing on Caracas, La Guaira, and the Valles de Aragua. This forced the Spanish commander La Torre to send about 1,000 men to stop Bermúdez and protect his rear.

The Patriot army moved from San Carlos to Tinaco. On June 24, from the heights of Buenavista hill, Bolívar observed the Spanish position. He realized it was too strong to attack from the front or south. So, he ordered his divisions to move left and attack the Spanish right flank, which was unprotected. This maneuver, carried out by the divisions of José Antonio Páez and Cedeño, aimed to outflank the enemy.

The Battle of Carabobo was fought on June 24, 1821, in the Sabana de Carabobo. It was a battle between the armies of Gran Colombia, led by Simón Bolívar, and the Kingdom of Spain, led by Marshal Miguel de la Torre. The battle was a decisive victory for independence. It was crucial for freeing Caracas and the remaining Spanish-held territory. Venezuela's independence was fully secured in 1823 with the Naval Battle of Lake Maracaibo and the capture of Castillo San Felipe in Puerto Cabello. This victory allowed Bolívar to begin his Campaigns of the South while his officers finished the fight in Venezuela.

On June 29, Bolívar's troops entered Caracas. Many white inhabitants had left the city, and houses had been looted. About 24,000 people left Venezuela for the Caribbean islands, the United States, or Spain. Bolívar ordered that all possessions of those who had left, including their crops, be taken by the government.

The Naval Battle of Lake Maracaibo was a naval battle fought on July 24, 1823, in the waters of Lake Maracaibo in Zulia, Venezuela. This battle finally sealed Venezuela's independence from Spain. It was a decisive action in the naval campaigns of the Independence.

The Spanish had managed to retake the provinces of Coro and Maracaibo, giving them a significant amount of territory in western Venezuela. The Republic's authorities ordered a naval blockade of the country's coasts. Admiral Padilla forced his way into Lake Maracaibo on May 8, 1823. After several smaller actions, the main battle took place on July 24, 1823, resulting in a complete victory for the Colombians. The defeat at Lake Maracaibo made the Spanish commander Morales's position impossible, and he surrendered on August 3.

After the battle, Admiral Padilla ordered his fleet to stay in the area. Soon after, he went to the Ports of Altagracia to repair his ships. The Spanish commander Ángel Laborde went to the castle, then escaped to Puerto Cabello, and finally to Cuba. The Patriots lost 8 officers and 36 crew members killed, and 14 officers and 150 crew members wounded. The Royalists suffered even greater losses, with 69 officers and 368 soldiers and sailors taken prisoner.

In just two hours of fierce fighting, the battle was decided. This opened the way for talks with Captain General Francisco Tomás Morales. On August 3, he was forced to surrender the rest of the Royalist fleet, the city of Maracaibo, San Carlos Castle, San Felipe Castle in Puerto Cabello, and all other Spanish-held areas. On August 5, the last Spanish officer left Venezuelan territory. Venezuela was finally free.

Gran Colombia (1819-1830)

This period, from 1819 to 1830, saw Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador united as one country called Gran Colombia. However, problems leading to its breakup started almost from the beginning. Gran Colombia was created in 1819 by the Congress of Angostura and organized by the Congress of Cúcuta, following the Constitution of Cúcuta.

By 1827, the union of Gran Colombia (which Ecuador had joined in 1823) was in crisis. Bolívar and others tried to stop it from falling apart, but their efforts were not enough. In 1830, New Granada, Venezuela, and Quito separated. On December 17 of that year, Bolívar died. The Congress of Valencia, which met from May 6, 1830, chose deputies to discuss the breakup of Gran Colombia and Venezuela's separation.

What Were the Results of Independence?

Spain finally recognized Venezuela's independence on March 30, 1845. This happened through a peace and friendship treaty between the governments of Queen Isabel II of Spain and Venezuelan President Carlos Soublette.

The Federal Constitution of 1811 established that all citizens were equal before the law. Noble titles and special privileges were removed. Laws that treated "pardos" (people of mixed race) badly were repealed. The right to property and safety was also recognized. These rules have stayed in Venezuela's later constitutions. However, inequality between social groups continued, but now it was based on wealth, not ethnicity.

The Federal Constitution of 1811 also confirmed a ban, given on August 14, 1810, by the Supreme Junta of Caracas, on bringing new black slaves into the country. However, slavery itself continued until 1854, when President José Gregorio Monagas finally ended it.

Between 1821 and 1823, the Spanish were ordered to leave Venezuelan territory. Only those who had supported the independence movement and elderly people over 80 were allowed to stay.

People have different ideas about what kind of revolution Venezuelan independence was:

- Some say it was mainly a political revolution. They believe that many of its main leaders were from the local rich families who didn't want to change the social inequality too much, so they could keep their power.

- Others think it was a social revolution. They point out that many other social groups (like pardos, Indians, and blacks) initially didn't support independence. These groups wanted big changes to society and the economy to create a more equal country.

See also

In Spanish: Independencia de Venezuela para niños

In Spanish: Independencia de Venezuela para niños