African hawk-eagle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids African hawk-eagle |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| in Namibia | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Aquila

|

| Species: |

spilogaster

|

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The African hawk-eagle (Aquila spilogaster) is a large bird of prey found in tropical Sub-Saharan Africa. Like all eagles, it belongs to the Accipitridae family. This eagle has feathered legs, which means it's part of the Aquilinae group. African hawk-eagles live in different types of woodland, including savanna and hilly areas, especially dry forests. They build large stick nests, about 1 meter (3 feet) wide, in tall trees. Usually, they lay one or two eggs.

African hawk-eagles are strong hunters. They mostly catch small to medium-sized mammals and birds. Sometimes, they also eat reptiles. Their call is a sharp kluu-kluu-kluu. The African hawk-eagle is considered a stable species. The IUCN lists it as a species of Least Concern, meaning it's not currently at risk.

Contents

What is the African Hawk-Eagle?

Its Place in the Eagle Family

The African hawk-eagle is part of the Aquilinae subfamily, also known as "booted eagles." This group includes about 38 species, all known for their feathered legs. The Bonelli's eagle (Aquila fasciata) was once thought to be the same species as the African hawk-eagle. However, scientists found many differences between them. These differences include how they look, their life habits, and where they live. Now, almost everyone agrees they are separate species.

Even though they are different, the Bonelli's eagle and the African hawk-eagle look similar. They are considered "sister species." In 2014, DNA research moved both species to the genus Aquila. This is the same group as the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). Another eagle, the Cassin's hawk-eagle (Aquila africana), was also moved to this group.

How to Identify an African Hawk-Eagle

Appearance of Adults and Young Eagles

The African hawk-eagle has a small head but a long neck and a noticeable beak. It also has a long tail and strong, feathered legs with large feet. These eagles often perch low in tall trees, hidden by leaves.

Adult African hawk-eagles look mostly black and white. Their upper parts are slate black-grey, and their undersides are whitish. Up close, you can see small white spots on their back and wings. Their tail is grey with thin dark bars and a wide dark band near the tip, ending in a white tip. The underside of the adult eagle is white with small, bold black streaks.

Interestingly, male and female adults can sometimes be told apart by their markings. Females usually have more streaks on their underside than males. The thighs and lower belly of adults are whitish.

Young African hawk-eagles look very different. They are dark brown on top with some pale edges. Their head has light black streaks, and their tail is more clearly barred than adults. Their underside is a reddish-brown color. As they grow older, their upper parts get darker, and their undersides become paler and more streaked. By four years old, they look like adults. Adult hawk-eagles have bright yellow eyes, while young ones have hazel-brown eyes. Their beak and feet are yellow at all ages.

How They Look in Flight

When flying, the African hawk-eagle looks like a medium-sized raptor. It has a small but noticeable head, a longish tail, and wings that are not too long or wide. They fly with strong, shallow wing beats. When gliding or soaring, their wings are spread wide.

Adult African hawk-eagles have a pale whitish-grey area on the upper side of their wings, near the base of the main flight feathers. This area extends into dark grey patches on the secondary feathers, which have black tips. From below, their wings show black trailing edges that stand out against their greyish-white flight feathers.

Young African hawk-eagles in flight have reddish-brown underwings that match their body. Their wings have varying dusky edges. The tail is thinly barred and the primary feathers are white at the base.

Size of the African Hawk-Eagle

The African hawk-eagle is a small to medium-sized eagle. It can look surprisingly large when perched because of its long neck, long legs, and upright posture. Females are usually about 5% larger and up to 20% heavier than males. However, their feet and talons are similar in size.

These eagles are typically 55 to 68 centimeters (22 to 27 inches) long. Some large females can reach up to 74 centimeters (29 inches). Their wingspan ranges from 130 to 160 centimeters (4 feet 3 inches to 5 feet 3 inches). Males weigh between 1,250 to 1,750 grams (2.8 to 3.9 pounds). Females are heavier, weighing from 1,480 to 2,470 grams (3.3 to 5.4 pounds).

Their talons are very large for their size. For example, the main rear talon (hallux claw), which they use to kill prey, can be around 38 millimeters (1.5 inches) long. This is similar to the talon size of much heavier eagles.

How to Tell Them Apart from Other Eagles

The African hawk-eagle usually lives in different areas than its closest relative, the Bonelli's eagle. This means they rarely meet. The Bonelli's eagle is larger, has a broader head, shorter neck, longer wings, and a shorter tail. Adult Bonelli's eagles are lighter brown on top and lack the pale wing patches seen on African hawk-eagles. Their undersides are creamy with fewer strong markings.

Another similar bird is the Ayres's hawk-eagle (Hieraaetus ayresii). However, it is smaller and rounder-headed. The Ayres's hawk-eagle also lacks the pale "windows" on its upper wings and has more even streaks on its underside. Unlike the African hawk-eagle, the Ayres's hawk-eagle has white "landing lights" under its wings.

The Cassin's hawk-eagle (Aquila africana) looks quite similar in shape. But it lives in thick forests, while the African hawk-eagle prefers drier woodlands. The African hawk-eagle is larger, has shorter tail, and longer wings. It also has more markings on its underside.

Sounds They Make

The African hawk-eagle is usually quiet when it's not breeding season. Its main call is a musical, fluting klooee. This call is often heard when a pair of eagles are communicating. It can sound a bit like the call of the Wahlberg's eagle (Hieraaetus wahlbergi), but the African hawk-eagle's call is shorter and softer.

The main call can be repeated or turn into klu-klu-klu-kleeee or kluu-kluu-kluu. They use this longer call during courtship or when they are aggressive, like chasing other raptors away from their nest. Near the nest, they might make repeated kweeooo or ko-ko-kweroo sounds, especially when building or fixing the nest. A female might make a squealing skweeyra call when she wants food from the male. They also make softer "conversational" sounds. Young eaglets ask for food with a high-pitched, insistent wee-yik wee-yik, wee-yik call.

Where They Live and What They Like

Their Home Across Africa

The African hawk-eagle lives across most of Sub-Saharan Africa. You can find them as far north as eastern Eritrea and parts of Ethiopia. They are less common in West Africa, but can be found in southern Senegal, The Gambia, and other countries like Ghana and Nigeria. In central and East Africa, they live in southern Chad, South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania.

In southern Africa, their range includes Angola, Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and parts of Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. They are almost gone from Eswatini. While some reports mention them as far south as the Cape Province in South Africa, these are likely just eagles that wandered there, not a regular population.

Their Favorite Places to Live

These eagles prefer well-wooded areas. They like tropical broadleaf woodlands and the edges of woodlands within the savanna. They usually avoid very dense forests. They can also live in thorny areas like the veld, especially near riparian zones (areas along rivers), where taller trees can grow. Woodlands with Miombo and Mopane trees are very important for them in southern Africa.

African hawk-eagles generally prefer dry areas. However, they also need some moderate rainfall. They avoid very rainy places and very dry deserts. Access to water, like rivers or watering holes, is often important. These areas allow tall trees to grow in dry regions and often attract prey. Sometimes, they are seen in more open savannas and semi-desert areas. They usually stay away from evergreen forests and mountainous areas.

While they have been known to nest on cliffs in Kenya, this is rare for them. They have also been seen in farmland and sometimes nest in tree plantations. However, they typically need protected areas to breed successfully. African hawk-eagles can be found from sea level up to about 3,000 meters (9,800 feet), but they mostly live below 1,500 meters (4,900 feet).

What They Eat and How They Hunt

A Powerful Hunter

The African hawk-eagle is a very aggressive and bold hunter. They use their strong feet as their main hunting tool. They often hunt by sitting quietly on a hidden perch for a long time, scanning for prey. When they spot something, they quickly swoop down from their perch, staying low to the ground. They use trees and bushes to hide their approach until they are very close to their prey. Their flight is very quiet, so prey often doesn't hear them coming.

These eagles often wait near places where prey gather, like waterholes or clearings. They can also fly above the ground and catch any prey they surprise. While they can catch birds in the air, they usually prefer to catch them on the ground. Sometimes, they will chase prey, even on foot, into thick bushes. It's rare for them to dive from high in the sky to catch prey.

African hawk-eagles often hunt together in pairs. They seem to work as a team, with one eagle distracting the prey while the other attacks. Their sister species, the Bonelli's eagle, also hunts in pairs. One amazing story tells of a pair of African hawk-eagles using a mesh fence to trap guineafowl. Another pair regularly perched near a fruit bat colony to catch bats.

What's on the Menu?

Wild African hawk-eagles usually hunt smaller prey than what trained eagles might catch. Their typical diet includes medium to large-sized birds and small to medium-sized mammals. They sometimes eat reptiles and even insects. Birds can make up 74-86% of their diet, and mammals can be 54-70%.

Because they keep their nests very clean and often hide their perches, we don't know as much about their diet as we do for some other eagles. However, what we do know shows they are very powerful predators. They are opportunistic, meaning they will eat whatever suitable prey is available.

When they catch mammals, they usually choose ones weighing between 300 grams (10.6 ounces) and 4,000 grams (8.8 pounds). Large ground-feeding birds are a favorite. These include francolins, spurfowls, and guineafowls, as well as smaller bustards and hornbills. In Zimbabwe, helmeted guineafowl (which are similar in size to the eagle) and Swainson's spurfowl (about half the eagle's size) were common prey.

In some areas, like the Matobo Hills in Zimbabwe, hyraxes were a very important food source, making up over half of the eagles' diet by weight. They also caught scrub hares and yellow-spotted rock hyrax. In Tsavo East National Park, Kirk's dik-diks (a small antelope) were the main prey. Young dik-diks were especially targeted. Other prey in Tsavo East included red-crested korhaan and common dwarf mongoose. In Namibia, meerkats were a significant part of their diet.

They also eat various other birds, from weavers to herons. Occasionally, they might take ostrich chicks, geese, plovers, cuckoos, and different types of dove. Domestic chickens are sometimes caught near farms, but they are not thought to be a major threat to poultry. Other mammals they eat include squirrels, rats, fruit bats, and bushbabies. Larger mammals like mongooses and hares, which can be as heavy as the eagle itself, are also hunted. They have even been known to attack young antelopes like klipspringers and steenboks. The largest prey recorded was a lechwe weighing about 5,000 grams (11 pounds).

Eating reptiles is less common, but they do catch snakes (including cobras) and lizards. One amazing record shows an African hawk-eagle catching a large African rock python. They rarely eat carrion (dead animals), but one pair was seen feeding on a dead southern reedbuck for three days.

Who Else Hunts in Their Territory?

The African hawk-eagle lives in an area with many other birds of prey. They share prey and habitats with both smaller and larger raptors. In Tsavo East National Park, they shared many prey items with tawny eagles, bateleurs, and martial eagles. Tawny eagles and bateleurs are about 25% larger than the African hawk-eagle, while the martial eagle can be three times bigger.

The African hawk-eagle is unique among these four eagles in Tsavo East because it nests in woodlands, not open savannas. This helps reduce competition. All four eagles mostly hunted Kirk's dik-diks. Their nesting times were also slightly different, which helped spread out the hunting pressure on dik-diks.

In Zimbabwe, African hawk-eagles also nested in different areas than other large eagles like the crowned eagle and Verreaux's eagle. While all three hunted hyraxes, the larger eagles usually caught much bigger hyraxes than the hawk-eagles. The African hawk-eagle was found to have the most varied diet among the large raptors in that region.

African hawk-eagles are known to be aggressive towards larger raptors. They often attack crowned and Verreaux's eagles if they fly near their territory. This might be to protect their hunting grounds or just to chase them away. Adult African hawk-eagles have few known predators and are considered apex predators in their environment. They mainly focus on smaller prey than the much larger eagles they live with. They have been known to hunt barn owls and black-winged kites.

Life and Family of the African Hawk-Eagle

Living and Mating Habits

African hawk-eagles are usually solitary, but adult pairs often stay together, perhaps more than many other raptors. They establish their breeding territories with aerial displays. These displays are simpler than those of some related species. They usually involve circling together and calling. Males sometimes perform "sky dances," which are shallow up-and-down flights with little wing flapping.

During courtship, the male might dive towards the female, and she will turn to him, showing her claws. This mating ritual ends with the male bringing the female gifts of prey. This species is usually monogamous, meaning they pair for life. However, there might have been a case of one male having multiple female partners in Ethiopia.

The breeding season varies by region. North of the Equator, it's from October to April. In The Gambia, it's February to June. In East Africa, it's often April to January. In Uganda, eggs are laid from September to November. In southern Africa, the nesting season is from April to October, with most eggs laid in June. Nesting is timed to happen during the regional dry season.

Building a Home: The Nest

The nest is a very large, platform-like structure made of sticks. It's usually built in the main fork of a large tree or far out on a strong branch. Nests are typically 4 to 36 meters (13 to 118 feet) above the ground, often between 9 and 13 meters (30 and 43 feet). In southern Africa, a nest at 4.2 meters (14 feet) was considered unusually low.

Common trees used for nests include Acacia, Adansonia, Khaya, Terminalia, and even non-native Eucalyptus. Nests are often found near rivers. Rarely, nests might be built in a bush or on a cliff ledge, especially in East Africa. In southern Africa, some nests have been found on pylons (large electricity towers).

Nests usually have some shade, but some are exposed. In these cases, the female shades the young eaglet. The nest itself is usually 50 to 80 centimeters (20 to 31 inches) deep, but can be over 125 centimeters (49 inches) with repeated additions. The inside cup is about 25 to 30 centimeters (10 to 12 inches) wide, and the whole nest can be up to 100 centimeters (39 inches) across.

Eagles repair their nests by adding new layers of sticks to the rim. Building a new nest can take several months. Repairs take about 4 to 5 weeks, sometimes up to 8 weeks. The male often helps with repairs, but the female might be more active in building new nests. Females often add fresh green leaves to the nest. These eagles prefer to breed in specific areas with good nesting habitat. In one extreme case, the same group of trees near Pretoria was used by hawk-eagles from 1912 to 1978.

Eggs and Keeping Them Warm

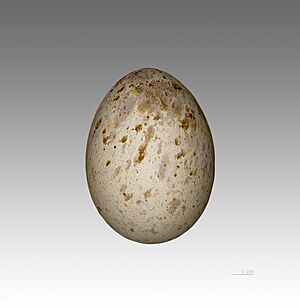

The African hawk-eagle usually lays 2 eggs. Sometimes, they lay 1 or 3 eggs. In Zambia, about half of the nests had one egg, and the rest had two. In Malawi, 80% of nests had two eggs. Only one nest in southern Africa was ever recorded with 3 eggs.

The eggs are chalky white with varied markings, from speckled with dull red to mostly plain. They measure about 59.5 to 75.2 millimeters (2.3 to 3 inches) tall and 46 to 55.7 millimeters (1.8 to 2.2 inches) wide. The average egg weighs about 87 grams (3.1 ounces).

If there are multiple eggs, they are laid about 3 or 4 days apart. Incubation (keeping the eggs warm) starts with the first egg. The female does most of the incubation, with the male bringing her food and taking short turns. Male incubation can last up to an hour, but is usually shorter. Both parents continue to add green leaves to the nest during incubation. The eggs hatch after 42-44 days.

Raising the Young Eagles

A chick takes just under 2 days to hatch. Newborn eaglets are covered in dark grey down, with whitish down on their belly and thighs. Their beak and feet are dull yellow. The first grey down is replaced by thicker, whiter down. By 2 weeks, only their head and back have grey down. At 3 weeks, their down is mostly white, and their first flight feathers start to appear. By 5 weeks, they are well-feathered on their underside. At 6 weeks, only their head, crop, and belly still have down. They are fully feathered a week later, except for their wings and tails.

At 2 days old, eaglets weigh about 80 grams (2.8 ounces). They grow quickly, reaching about 1,250 grams (2.8 pounds) by 49 days. At 5 days old, they can barely preen themselves. By 11 days, they can move slightly around the nest. Young eaglets spend most of their day sleeping, preening, and feeding. At 24 days old, they can defend the nest, stand well, and do clumsy wing exercises. However, they still can't tear meat off the food their parents provide. By 32 days, they are mainly fed by parents, stand well, and exercise their wings. At 50 days, they can feed themselves and flap their wings, showing signs of being ready to fledge. They might also preen a lot, nibble on sticks, and practice "killing" prey bones or sticks to improve their coordination.

Fledging (leaving the nest for the first time) happens between 60 and 70 days of age. After leaving the nest, young eagles stay with their parents for about 3 to 4 weeks. Some might stay with their parents for up to 2 months.

A 2008 study found that in nests with two chicks, the first-born chick almost always kills the second, smaller chick. This is common in many bird species, especially birds of prey. It ensures that at least one chick gets enough food to survive and thrive. In southern Africa, no cases of two successfully raised young were recorded. However, in Kenya, about 20% of nests produced two fledglings. The reasons for this difference are not fully understood.

Parental Care

Parental care can be divided into three stages. In the first two weeks after hatching, the female stays on the nest and keeps the chick warm. The male brings prey, but he has also been seen brooding and feeding the small eaglet. After two weeks, the chick is not brooded as closely.

In the second stage (2-4 weeks), the female spends less time on the nest but usually perches in the nest tree. The male still brings most of the prey, and the female continues to feed and shade the chick. In the third stage (from 4 weeks until fledging), parents spend much less time at the nest. The female might still sleep on the nest overnight, but possibly away from the eaglet. Only at a very late stage does the female start catching prey for the eaglet.

Nests are kept very clean. The female is known to remove pellets (undigested food) from the nest. Much of the bird prey is brought to the nest already plucked, which makes it hard for researchers to identify what they've eaten.

Parent African hawk-eagles are very aggressive in protecting their nest. They regularly dive at anything that threatens or approaches the nest. Humans are often attacked near the nest, especially if they try to climb towards it, which can result in painful injuries. This species is considered one of the most aggressive African eagles in defending its nest against humans, similar to the crowned eagle. They are much more likely to dive at humans than nesting Bonelli's eagles.

Breeding Success and Moving Around

In a 1988 study in Zimbabwe, scientists looked at 116 African hawk-eagle pairs to see how successful they were at breeding. They found that rainfall affected breeding success, when eggs were laid, and how many eggs were in a clutch. More rain meant more success, later egg-laying, and larger clutches.

The African hawk-eagle is usually a very settled raptor. It rarely leaves an area with good prey and habitat. However, one unsuccessful pair was recorded using 4 different nest sites in 9 years, which is unusual for this species.

Unlike many other African eagles, this species can usually breed every year. For example, at one nest site in Zimbabwe, there were only 2 years without breeding in 17 years. Overall, they produced about 0.82 young per nest per year. Other nests in Zimbabwe sometimes failed, and infertile eggs were a problem, leading to an average of 0.54 young per nest. In Kenya, 15 young were produced from 27 pairs over several years, averaging 0.56 young per pair per year.

The death rate for young African hawk-eagles (under 4 years old) can be very high in some places, up to 75%. This is mainly due to human activities, such as persecution and collisions with man-made objects like power lines.

Despite their reputation for staying in one place, young eagles can travel far from their birth areas. In southern Africa, young African hawk-eagles were found an average of 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) from where they were ringed as nestlings. One eagle traveled 795 kilometers (494 miles) from Limpopo in South Africa to Victoria Falls. This long journey might have been due to a long dry spell and less food.

Status of the African Hawk-Eagle

The African hawk-eagle has a very wide range and is a fairly common species. No major threats have been identified, but its population is thought to be slowly decreasing. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified its conservation status as "least concern". This means it is not currently at high risk of extinction.

BirdLife International estimated the total number of adult African hawk-eagles to be around 100,000 birds. However, they note that this data is not very strong. In the former Transvaal province of South Africa, there were thought to be about 1,600 pairs. In the whole southern African region, the estimated total was about 7,000 pairs.

A 2006 study found that African hawk-eagle numbers, along with other raptor species, have been declining quickly outside of protected areas in West Africa. Their numbers only seem to be stable within national parks. When comparing numbers from 2003-2004 to 1969-1973 in West Africa, declines were even found in protected areas. Overall, negative population trends have also been seen in southern Africa for some time.

Even though some claim declines in Malawi are due to people hunting African hawk-eagles for stealing poultry, the main reason is likely the widespread destruction of woodlands. The declines are strong enough in southern Africa that the species is thought to be extinct as a breeding bird in Eswatini.

Images for kids