British logistics in the Siegfried Line campaign facts for kids

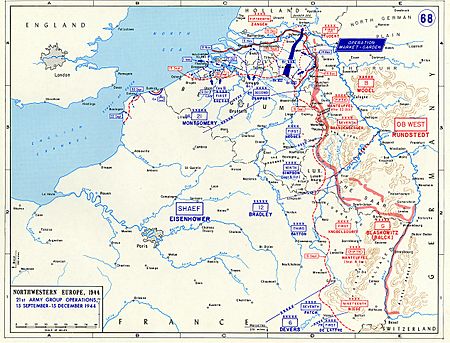

During World War II, British forces played a big part in the Siegfried Line campaign from September 1944 to January 1945. This campaign happened after the Allied armies chased the German forces out of Normandy. The Allies had landed in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944. The fighting was tough, and the British and Canadian armies moved slowly at first. But in July, they finally broke through the German defenses and advanced much faster than anyone expected.

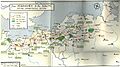

The British Second Army freed Brussels on 3 September. However, their attempt to cross the Rhine River using airborne forces in Operation Market Garden didn't work. Meanwhile, the Canadian First Army had the job of clearing the German forces from the English Channel coast. The important port of Antwerp was captured almost undamaged on 4 September. But it took a lot of fighting, known as the Battle of the Scheldt, to clear the Germans from the Scheldt estuary. This waterway was needed for ships to reach Antwerp. The port finally opened on 26 November. Antwerp was big enough to support both British and American forces, but German V-weapon attacks made it difficult to use.

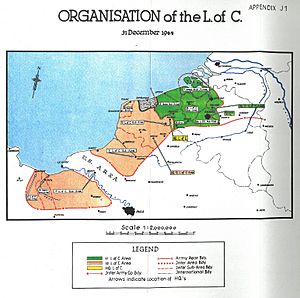

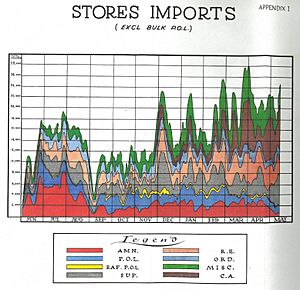

A new main supply area was set up near Brussels, with an advanced area near Antwerp. The old supply area in Normandy, which still held about 300,000 tons of supplies, was gradually closed down. This included 15 million food rations, which soldiers ate over time. Any supplies still needed by the 21st Army Group were moved to the new advanced base. The rest were sent back to the War Office. To get the railway system working again, bridges had to be rebuilt, and more trains brought in. Fuel was delivered by tankers and through the Operation Pluto pipeline. Civilian workers helped a lot at the bases. This allowed military personnel to go to the front lines. By the end of 1944, about 90,000 civilians worked for the 21st Army Group. Half of them worked in workshops, and 14,000 at the port of Antwerp.

British logistics during this campaign had huge resources. The main challenge for the supply teams wasn't if something could be done, but how quickly. They had learned a lot from earlier campaigns and kept getting better. The supply system was strong and flexible. It could support both fast attacks and slower operations.

Contents

How It Started

In the first weeks after the Allied invasion of Normandy, called Operation Overlord, the British and Canadian forces got their supplies from Gold Beach, Juno Beach, Sword Beach, and small ports like Port-en-Bessin and Courseulles. An artificial harbor called Mulberry harbour was built starting on 7 June. By 16 June, it could handle 2,000 tons of supplies daily. The Mulberry harbor handled about 12.5% of all Allied supplies in June. The port of Cherbourg and small ports handled 25%, and the beaches handled 62.5%. The Germans fought hard, and there were many casualties. The British advance was slower than planned because most German forces were fighting in their sector. By the end of July, it seemed unlikely that the Allies would capture the Seine River ports soon. So, work began to prepare the Mulberry harbor for winter, build up supplies for bad weather, and open the ports of Caen and Ouistreham.

At the same time, plans were made for a quick breakthrough of German defenses. When the American Operation Cobra succeeded on 25 July 1944, six more transport companies were sent from the United Kingdom. Plans were made to set up an advanced base near Le Havre. This was based on the idea that Germans would try to stop the Allies along the Somme River. But the Allied advance went further and faster than expected. The British Second Army's XXX Corps crossed the Seine on 25 August. The XII Corps followed two days later. Both corps crossed the Somme by 1 September.

To help the advance, transport vehicles from the VIII Corps were used. Most vehicles normally used for beaches and ports were also taken. This meant fewer supplies (from 16,000 to 7,000 tons per day) were shipped from the UK to France. The difference was made up by using supplies already stored in Normandy. These steps increased the number of transport units for the Second Army from 6 to 39 companies. Supplies were stored as far forward as possible in temporary areas called "cushions." Brussels was freed on 3 September, and Antwerp was captured almost undamaged on 4 September. But Antwerp couldn't be used as a port until the Germans were cleared from the Scheldt River, which ships needed to use.

Meanwhile, the Canadian First Army's II Corps crossed the Seine on 27 August. The British I Corps crossed three days later. At this time, there were no bridges over the Seine between Rouen and the sea. Also, no bridges upstream to Paris were intact, partly because of Royal Air Force (RAF) attacks. A strong tide made it hard to use temporary bridges and ferries. The Canadian Corps got supplies from roadheads (supply points) at Lisieux and Elbeuf. The First Canadian Army opened more roadheads near Dieppe and Abbeville on 3 September, and near Bethune on 15 September. Sometimes, temporary "kangaroo dumps" were set up in forward areas to help the advance. The Canadian roadheads didn't always have enough supplies in August and September because the Second Army had priority. But there were plenty of supplies in the main depots in Normandy, though these were now up to 300 miles (480 km) behind the front lines.

How Supplies Were Organized

On 1 September, the top Allied commander, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, took personal control of the ground forces from Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery. Eisenhower's headquarters now approved requests for things like coal and sent them to the War Office to handle. Montgomery remained the commander of the 21st Army Group, which included Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey's British Second Army and Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar's Canadian First Army. The 21st Army Group, including RAF personnel and German prisoners of war, had about 450,000 people. Montgomery was in charge of his own supplies, which was different from the American system.

Montgomery believed that managing supplies was a key part of war. He rarely started an attack until all the necessary supplies, especially ammunition, were ready. This sometimes meant he missed chances to attack quickly. American commanders were often more willing to attack even if supplies weren't perfect.

The main headquarters of the 21st Army Group moved to Brussels, finishing on 23 September. The 7th and 8th Base Sub Areas managed Antwerp and Ostend under Canadian command. The 4th Line of Communications Sub Area managed Brussels under British command. In September, these areas came under the control of the Headquarters of Lines of Communication. A new headquarters, the 16th Line of Communications Sub Area, was formed to manage bases and depots in the Somme area. In November, it moved to Belgium and took over the port of Ghent. The Headquarters of Lines of Communication, led by Major-General R. F. B. Naylor, moved to Roubaix in December to be more central. The 11th Line of Communications Area then took control of the advanced base in Belgium, while the 12th Line of Communications Area moved from Cherbourg to Amiens and took charge of bases in France.

The Canadian Army didn't have enough people to manage its own supply lines, so it shared the British ones. A Canadian administrative section was attached to the 21st Army Group headquarters. Its main job was to help the Canadian First Army with non-fighting administrative tasks.

Besides Canadians, the 21st Army Group also included soldiers from Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and France. These groups were organized and equipped like British Army units, which made supplying them easier. But language differences were still a challenge.

Construction of a new advanced supply base in Brussels began on 6 October. No. 6 Army Roadhead was set up there, and supply units started moving in. Most units needed fuel and food from the Second Army's resources. Also, managing civilian affairs in Brussels was a drain on resources. The roadhead was placed on the western side of Brussels because of the railway layout. But this meant army transport had to drive through Brussels' narrow, busy streets.

An army roadhead usually had two main supply depots, four smaller depots for issuing items, five fuel depots, and four mobile bakeries. The main depots held five days' worth of supplies for the army. The smaller depots handled supplies for local units, including RAF units. They also managed loading trucks and trains, and handling coal, fresh meat, and vegetables. The mobile bakeries could bake up to 44,000 bread rations daily. Fuel depots were managed by a special officer. About 26,000 tons of packaged fuel were kept at the roadhead.

Before the campaign, it was thought that the Second Army Troops Headquarters could manage the roadhead. But after fighting started, this headquarters was too busy managing the huge number of army troops. So, the army roadhead was controlled by the Second Army Headquarters. A special "administrative post" was created to supervise it. This post worked closely with the movement control group, which managed road and railway traffic.

Operation Market Garden

Eisenhower thought capturing industrial areas like the Ruhr was most important. Montgomery suggested a narrow attack, but Eisenhower wanted a wider one. So, Montgomery ordered the Second Army to cross the Rhine with airborne troops. The Canadian First Army was to capture Boulogne and Calais, then open Antwerp. Capturing Boulogne would help Operation Pluto, which involved laying pipelines under the English Channel to deliver fuel. It was believed that the Channel ports could support the 21st Army Group all the way to Berlin.

Montgomery planned to go around the Siegfried Line with an airborne operation called Operation Market Garden. "Market" was the airborne part, and "Garden" was the ground part. The Siegfried Line was a 2-3 mile (3-5 km) deep line of pillboxes, bunkers, trenches, and gun positions, protected by barbed wire and anti-tank obstacles called dragon's teeth. To support this, XXX Corps set up a supply point at Bourg-Leopold, which opened on 17 September. It was planned that another supply point would be set up at Arnhem after it was captured. This would support troops north of the Rhine, including the British 1st Airborne Division. Forces south of the Rhine, like the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Division, would get supplies from Bourg-Leopold. The supply units for the 1st Airborne Division followed the ground troops, carrying extra ammunition and two days' worth of supplies.

On 16 September, eight American truck companies started moving supplies between Bayeux and Brussels. They built up stocks for the two American airborne divisions. This operation was called the Red Lion. It ran until 18 October, delivering 650 tons of supplies daily. American divisions used British items like tires, but most other supplies came from American stocks. In an emergency, American troops could use British food.

Ground divisions carried six days' worth of supplies. Corps troops carried enough fuel for 150 miles (240 km), and armored divisions carried enough for 200-250 miles (320-400 km). These units carried double the usual amount of 25-pounder ammunition. The plan involved 20,000 vehicles moving along just one road. To avoid traffic jams, each division took only one workshop. Broken-down vehicles were pushed off the road. Traffic moved only one-way and only during daylight.

This plan of units carrying their own supplies worked well. By 19 September, traffic on the highway was so heavy that normal supply was impossible. No supplies could reach Arnhem because it hadn't been captured. So, efforts focused on stocking the Bourg-Leopold supply point. The American trucks arrived two days late on 20 September. They were also under strength and carried the wrong type of ammunition. The American divisions had no sea-based supply units, so they were given American trucks, and British and American troops helped issue supplies. The transport situation got worse when nearly 30 vehicles were lost in a German bombing raid on Eindhoven on the night of 20/21 September.

By 21 September, the plan to set up a supply point at Arnhem was dropped. It was decided to put it near Grave instead. But the road was cut by Germans south of Veghel. The 101st Airborne Division could get supplies from Bourg-Leopold, but the 82nd Airborne Division was cut off. Transport was ordered to wait for the road to reopen. Corps troops only had four days' rations, so they depended on the divisions. Help came when a large German supply dump was captured at Oss. It provided 120,000 rations per day for XXX Corps, though tea, sugar, and milk were missing.

The 101st Airborne Division and the Guards Armoured Division reopened the road by 3:30 PM on 23 September. But it was still under fire. The road was cut again on 24 September and didn't reopen until 26 September. By then, the whole operation had been called off, and the 1st Airborne Division had been pulled back.

Airborne Supplies

The airborne part of Operation Market began on 17 September. Troops carried 48 hours' worth of supplies. Plans for air resupply were set for four days, with an option to extend. On the second day, 18 September, only 35 Short Stirling aircraft were available to tow supply gliders. After that, there would be enough Stirlings and Dakotas. British and American equipment was different, with only a few common items like jeeps and fuel. Different equipment meant different packing needs.

The second air drop was delayed by fog on 18 September. Three gliders brought jeeps loaded with ammunition and supplies. But only two could be unloaded before German fire stopped the work. The divisional supply officer arrived and started setting up the supply area near the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek. The resupply drop that day mostly landed in German hands. But some supplies were collected and taken to the supply area using captured German vehicles.

Parachutes used for supply drops were colored to show what was inside: red for ammunition, white for medical supplies, green for rations, blue for fuel, yellow for signals equipment, and black for mail. The first big resupply drop on 19 September landed in the wrong place. 99 Stirlings and 63 Dakotas were used; 18 aircraft were lost. The next day, 2,000 rations were collected, enough for about a third of the division's needs. Also, some ammunition was collected. Fifteen aircraft were lost. On 21 September, German fighters attacked the supply planes, and 31 aircraft were lost. On the ground, only small amounts of ammunition were collected.

Some supply aircraft took off on 22 September but were sent to Brussels. The supply area was under mortar fire, and some ammunition caught fire. Another resupply attempt on 23 September brought some ammunition, but ammunition for PIATs (anti-tank weapons) and Sten guns was very low. There were only a few working jeeps to deliver supplies. The resupply drop for 24 September was canceled due to bad weather.

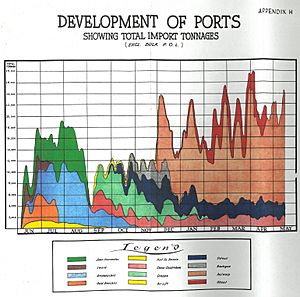

Ports

Channel Ports

By the end of August, two port groups operated the Mulberry harbor, Caen, and Ouistreham. The Canadian First Army's job was to capture the Channel ports. Rouen was captured on 30 August. Le Tréport and Dieppe were taken on 1 September. Dieppe's port was almost intact, but the approaches were heavily mined. It took several days to clear the mines. The first ship docked there on 7 September. By the end of September, Dieppe could handle 6,000-7,000 tons per day. Le Tréport was used mainly by the RAF for large items.

A big attack was needed to capture Le Havre. When the Germans surrendered on 12 September, the port was badly damaged. The Allies decided to give this port to the American forces.

Boulogne was captured on 22 September but was badly damaged. Most port equipment was destroyed, and 26 sunken ships blocked the harbor. The Royal Navy cleared a channel, and two ships could pass by 12 October. Repairs allowed five ships to dock. Boulogne handled about 2,000 tons daily until early 1945. It received 9,000 personnel, 10,000 vehicles, and 125,000 tons of supplies.

The German guns at Calais had to be silenced to help clear mines for Boulogne. So, Calais was captured on 29 September. It was also badly damaged. Repair work focused on building a railway terminal for ships that could carry trains. Calais became the main port for receiving personnel in the British sector. Supplies were not unloaded there until January, and it handled only about 350 tons daily.

Ostend was captured on 9 September. The naval team had to clear 14 sunken ships blocking the harbor. A channel was cleared by 24 September, allowing ships to enter. Some quays were destroyed, but others were repaired by the Royal Engineers. By the end of September, Ostend could handle 1,000 tons of cargo daily. This rose to 5,000 tons a day by the end of November, not counting bulk fuel. Ostend was very efficient, turning around ships faster than any other port.

In early September, the 21st Army Group had limited shipping because the captured Channel Ports couldn't handle large vessels. The ports could discharge about 10,000 tons daily. The ships had been used constantly since D-Day and needed repairs. Bad autumn weather also disrupted operations. The Mulberry harbor was damaged by a gale in early October, and fuel discharge there stopped. With Boulogne open, two deep-water berths became available. The port capacity was enough to keep the 21st Army Group supplied and build a small reserve, but not for major operations.

Antwerp

Although Antwerp was captured on 4 September, its port couldn't be used because the Scheldt estuary, which led to the port, was still controlled by Germans. A port construction company arrived on 12 September and started repairing the port.

On 15 October, Montgomery received a message that made him prioritize opening Antwerp. He ordered both the British Second Army and the Canadian First Army to focus on the Battle of the Scheldt. A new supply point, No. 9 Army Roadhead, was set up in the Termonde-Alost-Ghent area, connected by railways. It opened on 8 October.

During Operation Market Garden, the supply point at Bourg-Leopold had grown very large with many US Army supplies. The Second Army took it over as a new army roadhead, No. 8 Army Roadhead. It was a good location with roads and railways, but it lacked covered storage. So, supplies often had to be stored outside. Stocking this new roadhead began on 4 October, mostly by rail.

During Operation Infatuate, which aimed to open Antwerp, British commandos captured Flushing on 4 November. This brought both sides of the Scheldt under Allied control. Mine-clearing operations began on 4 November. Fifty mines were cleared on the first day. On 26 November, the naval officer in charge announced that mine-clearing was complete.

The port of Antwerp opened to smaller ships that day and to deep-draft ships on 28 November. The first ship to arrive was the Canadian-built SS Fort Cataraqui. The quays were cleared, and the Kruisschans Lock was repaired by December. Antwerp could now receive ships directly from the UK, the United States, and the Middle East. The first order from the US was for 18,000 tons of food. Later orders were just for flour and meat, as enough other goods were in the UK. Fresh meat from South America became available daily from 2 December 1944.

Antwerp had 26 miles (42 km) of quays, over 600 cranes, and 900 warehouses. It also had huge fuel storage tanks. There were plenty of workers, and it was well-connected by roads, railways, and canals. The Germans had removed 35 miles (56 km) of railway track and damaged marshalling yards. A special organization was set up to manage dredging the Scheldt.

The Allies decided that Antwerp would handle both American and British supplies, under British control. A special combined staff was created. Overall command of the port was given to the Royal Navy. US forces had priority for roads and railways leading southeast to Liège, while the British had those leading north and northeast. A joint organization was created to coordinate transport. The goal was to unload 40,000 tons per day. However, Antwerp was not an ideal base port because it lacked warehouse and factory space. This made it hard to clear congestion. The area around the port quickly filled with supply dumps.

Despite minor damage, Antwerp often failed to meet its tonnage targets. This was mainly due to not enough warehouse space, a shortage of railway cars, and delays in opening the Albert Canal for barges. The canal was supposed to open on 15 December but was delayed until 28 December. Temporary lighting was installed at the Antwerp quays in December to allow 24-hour work.

German V-weapons attacks, which started on 1 October, also caused problems. These attacks seriously affected the availability of civilian workers, so military workers had to be brought in. Still, the number of civilians at the port rose to over 14,000 by January 1945. US Army supplies were moved directly from the quays to depots near Liège and Namur, but these were also frequent targets of V-weapons.

By the end of 1944, 994 V-2 rocket and 5,097 V-1 flying bomb attacks had hit targets in Europe. These attacks killed 792 military personnel and 2,219 civilians in Antwerp. Four berths at the port were damaged in an attack on 24 December. Two large cargo ships and 58 smaller vessels were sunk between September 1944 and March 1945. But the damage wasn't enough to stop the port from working.

German E-boats tried to disrupt convoys to Antwerp, but Allied destroyers drove them off. RAF Bomber Command also attacked E-boat bases. Seehund midget submarines also sank some ships. Aerial mining was dangerous because one large ship sunk in the Scheldt could stop all traffic. A major German aerial mining effort happened on 23 January 1945, but it was the last one against Antwerp.

Ghent

The Allies knew it was risky to rely too much on Antwerp. So, the inland port of Ghent was developed as a backup. It could be reached via the Ghent–Terneuzen Canal and handle ships with drafts up to 24 feet (7.3 m). It could handle up to 16,000 tons per day. Ghent was operated under joint US-British control. British engineers quickly repaired the sea locks at Terneuzen, which had been badly damaged. Dutch engineers thought it would take six months, but the Royal Engineers did it in just two. Ghent had only been used by Germans for barge traffic, so it needed dredging. An American dredge helped with this. Together with the Channel ports, Ghent provided enough capacity to meet the Allied armies' minimum needs.

Transport

Roads

A Field Maintenance Centre (FMC) usually held two days' rations, one day's general maintenance, two or three days' worth of fuel (about 200,000 liters), and 3,500 tons of ammunition. Each corps had transport companies with 222 3-ton trucks, 12 10-ton trucks, and 36 dump trucks. The dump trucks were always busy with construction tasks. A corps usually needed 800-1,000 tons of supplies daily, and its transport had to carry 900 tons. The corps' transport wasn't enough, so they had to borrow trucks from armies or divisions.

Most infantry divisions in the 21st Army Group organized their transport by type of supply: one company for general supplies, one for fuel, one for artillery ammunition, and one for other ammunition. Armored divisions had a similar setup. Organizing by type of supply made transport easier and helped when trucks were needed for other tasks. The goal was to keep transport busy.

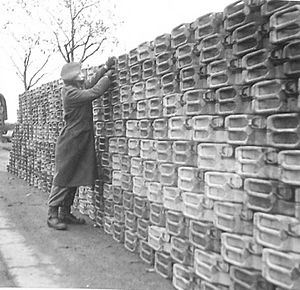

Several methods were used to increase road transport capacity. The First Canadian Army converted a tank transporter trailer into a load carrier. The Second Army was impressed and ordered more conversions. A converted tank transporter could carry 16.5 tons of supplies, 36 tons of ammunition, or 10 tons of fuel. These could carry a lot but needed careful traffic control to avoid narrow roads. More vehicles were given to transport companies, and some amphibious trucks (DUKWs) were re-equipped with regular trucks. Eight more transport platoons were formed from anti-aircraft units.

On 3 September, the 21st Army Group urgently requested more transport companies. Two were formed from the Anti-Aircraft Command and two from the War Office Airfields Transport Column, and shipped within six days. A second request on 15 September brought 12 more transport companies. Five of them arrived pre-loaded with fuel, five with supplies, and two empty.

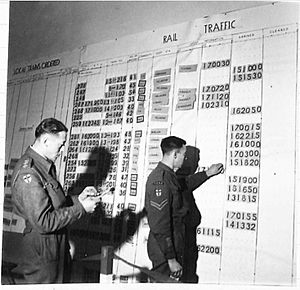

On 19 September, the 21st Army Group Headquarters took control of transport through an organization called TRANCO. Two officers were in charge of transport north of the Seine and two south. They managed road patrols and staging camps and reported on transport availability. Traffic became more routine in October, and TRANCO was ended. However, until the railway bridge at Ravenstein was repaired in December, the Second Army's operations southeast of Nijmegen still relied on roads.

To save manpower, RASC motor transport units were reorganized in October. Sixteen army transport companies became general transport companies. Fuel transport companies were also reorganized.

In November, Belgian Army units were formed into transport companies. After training in the UK, they took over the equipment of the companies loaned by the War Office. This allowed the British personnel to return to the UK for new assignments. This transport pool was directly controlled by the 21st Army Group headquarters.

To give transport companies a break, captured German horses, wagons, and saddles were used. Hired Belgian civilian animal transport also helped. In early December, 9,500 tons of supplies were moved by animal transport, mostly in the Antwerp area.

Two-way traffic on narrow roads caused a lot of damage. Vehicles driving on the road edges damaged the road. Wooden posts were driven into the ground to prevent this. Stone for road repair came from quarries, and slag from zinc works was used for pitch. In January 1945, the Royal Engineers produced 170,000 tons of stone.

Railways

It was very important to get the railway system working again quickly. The biggest problem was destroyed bridges, especially over the Seine. In northern France, the damage was less, and repairs were faster. British Army, civilian, and prisoner of war workers did this. From 10 September, supplies from Normandy started moving by rail. Trucks then took them across the Seine to the Beauvais area, where they were reloaded onto trains and sent to Brussels. A new 529-foot (161 m) railway bridge at Le Manoir was finished on 22 September, allowing trains to cross the Seine. By making a detour, trains could reach Brussels even with two bridges over the Somme down. In November and December, the Seine rose to its highest level since 1910, but the bridge at Le Manoir held.

While the US Army had its own railway units, the British forces relied on French and Belgian railway authorities to operate the Amiens-Lille-Brussels line. In return for military help in restoring the rail network, local authorities agreed that military traffic had priority. France had about 12,000 locomotives before the war, but only about 2,000 were working by September 1944. With quick repairs, this rose to 6,000. But it was still necessary to bring in British-built locomotives. Plans called for a thousand engines to be brought over. Their delivery was slow because of limited space at Cherbourg, the only port that could receive them. This changed when Dieppe opened as a railway ferry terminal on 28 September. By the end of November, 150 locomotives had been landed at Dieppe and Ostend using special ships with rails. Calais also started receiving trains on 21 November.

Having enough trains was only part of the problem. Railway operators also dealt with damaged tracks, too few staff, and broken telephone systems. Coordinating the system was the job of the Q (Movements) Branch at 21st Army Group Headquarters. Repairing the railway system in the Netherlands involved rebuilding bridges over many rivers and canals. Germans had destroyed almost all railway bridges. By 6 October, the line reached Eindhoven.

The Americans took over all rail traffic west of Liseux on 23 October. Nineteen bridges were opened in November, and work was ongoing on twenty-two more. By the end of the year, 75 railway bridges were rebuilt. Most repairs to the Antwerp marshalling yards were complete. With the bridge at 's-Hertogenbosch finished, trains ran from Antwerp to supply points near the front line.

Air

The 21st Army Group didn't use air resupply much during the Normandy campaign. But demand increased greatly when the 21st Army Group moved past the Seine. In the first week of September, 1,600 tons of fuel and 300 tons of supplies were delivered to airfields near Amiens. The next week, with German resistance growing, ammunition became the priority. 2,200 tons of ammunition, 800 tons of fuel, and 300 tons of supplies were delivered.

By this time, airfields around Brussels were repaired and became the main destination for air freight. Over the next five weeks, the RAF delivered 18,000 tons of air freight to Brussels' Evere Airport alone. Sometimes, more than a thousand aircraft arrived in a single day. This was more than could be cleared by the available road transport, so temporary dumps were set up at the airfields. A special transport unit trained in handling air freight was brought in. It took control of two supply depots and received an average of 400-500 tons of cargo daily.

Pipelines

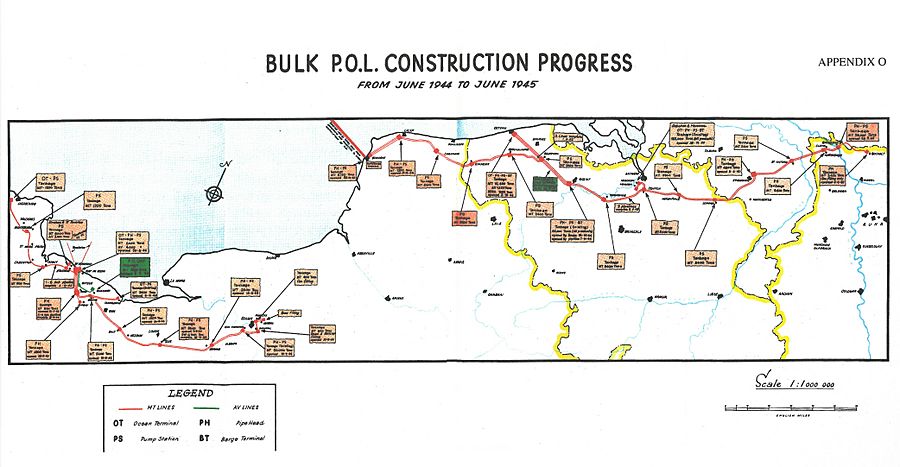

Operation Pluto was a secret project to bring bulk fuel directly from the UK using underwater pipelines laid across the English Channel. Two new types of pipe were developed. One, called Hais, was a flexible pipe like a telegraph cable. The other, Hamel, used steel pipe wound around huge floating drums called "Conundrums."

Three ships were fitted with cable-laying equipment. Special barges were used in shallow waters. Two systems were planned: "Bambi" from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg, and "Dumbo" from Dungeness in Kent to Boulogne.

The project started slowly due to delays in capturing Cherbourg, mine-clearing, bad weather, and technical problems. Pumping began on 22 September. But by then, Cherbourg harbor was open to tankers, and the 21st Army Group was in Belgium and the Netherlands. The Bambi project stopped on 4 October after 935,000 liters had been delivered.

Meanwhile, Boulogne was captured on 22 September and opened on 12 October. Work switched to the Dumbo system, which had a much shorter pipeline distance and was closer to where the 21st Army Group was operating. A Hais pipeline was laid and started pumping on 26 October. It stayed in use until the end of the war.

Boulogne had poor railway facilities, so the pipeline was connected to an overland one to Calais, where better railway connections were available. This extension was completed in November. By December, 17 pipelines were laid, and Dumbo was providing 1,300 tons of fuel per day. The overland pipeline was extended to Antwerp, then to Eindhoven in the Netherlands, and finally to Emmerich in Germany. Large storage tanks were built in Boulogne and Calais.

Fuel was also moved by barges. Floating bridges over the Seine were removed to allow barge traffic. Low bridges over canals in Belgium and the Netherlands were also removed and replaced. Repairing the canal system involved raising sunken barges, removing other blockages, and repairing damaged locks. Severe weather caused the canals to freeze in January and February 1945.

Supplies and Services

Food

Because of Allied air attacks, few large German supply dumps were captured until Brussels was reached. Large amounts of food were found there. For a time, these made up a big part of the rations given to troops. These included unusual items for British soldiers, like pork and garlic-flavored foods. This helped break the monotony of the standard field rations. To make German rations meet British standards, extra tea, sugar, and milk were added.

The advanced food supply organization around Antwerp was spread out in three locations: four depots in Antwerp, five in Ghent, and three in Brussels. Large refrigerated storage areas were provided for fresh meat and vegetables, which were now regularly given out. Some food items now arrived directly from the United States, avoiding double handling in the UK. By the end of 1944, the base had 100,000 tons of storage capacity and held 29 million rations.

There was enough cold storage in the base area for the 21st Army Group. Eighty refrigerated railway wagons were acquired. But in cold weather, frozen meat could be moved in ordinary covered wagons. For Christmas, 300 tons of frozen pork arrived at Ostend in late November. To save bakers, who were in short supply, the 21st Army Group reorganized its eight field bakeries into fourteen mobile field bakeries. This increased bread-making capacity and saved 200 bakers.

Fuel

A fuel depot opened in Brussels, supplied by railway tank cars until Antwerp opened. Antwerp had 300,000 tons of fuel storage, shared with the Americans. Ostend became the main port for fuel and was linked by pipeline to the largest British fuel installation at Ghent, which had 50,000 tons of storage. During the advance, the Canadian First and British Second Armies had mobile refueling centers. But these were transferred to the 21st Army Group's control in November. Storage areas for packaged fuel were located at Antwerp (35,000 tons), Diest-Hasselt (40,000 tons), Ghent (35,000 tons), and Brussels (20,000 tons).

During the rapid advance, soldiers sometimes didn't return jerricans (fuel cans). Discarded cans were often taken by civilians, leading to a shortage that took months to fix. Stocks in the UK ran low. To help, fuel was issued in bulk to units along the supply lines. Refueling stations were set up for road convoys. A salvage effort recovered over a million jerricans. By the end of 1944, the 21st Army Group held 245,000 tons of packaged and bulk fuel, enough for 58 days. More was held at army roadheads.

The War Office had a reserve of 30,000 tons of fuel in non-returnable 4-gallon tins. These were shipped to the 21st Army Group to help with the shortage. However, jerricans were preferred because they were better for shipping and handling, and fuel loss was minimal. With jerrican discipline restored, there were worries that using non-returnable tins might make soldiers less careful.

During the German occupation of Belgium, a company called Union Pétrolière Belge (UPB) controlled Belgian oil companies. The 21st Army Group kept their services for distributing civilian petroleum products. This was limited to essential services, and demands were met from military stocks. In return, the oil companies let the Allies use their plants and employees.

Coal

Large shipments of coal from the UK started in August 1944. They increased from 60,000 tons in September 1944 to 250,000 tons per month in early 1945. This used up a lot of shipping space. The coal sections of the Allied headquarters were combined. Some coal mines in France and Belgium started producing again in October.

A severe coal shortage developed in Belgium in December. This threatened to stop the civilian economy and military railway traffic. Coal was needed for trains and many other military uses, like power stations, hospitals, and bakeries. Units were given an allowance of 4 pounds (1.8 kg) per man per day, often supplemented with firewood. These military needs took priority over civilian uses, like electricity for heating and lighting. Luckily, both US and British armies used oil for cooking. Strict limits were placed on electricity, which also affected factories used for military purposes.

The price of coal on the black market was very high, leading to a lot of theft. Guards had to be posted at mines and on coal trains. The main problem in Belgian coal production was a shortage of wooden pit props, which came from the Ardennes. About 1 ton of pit props was needed for every 40 tons of coal. Seven of the twelve British and Canadian forestry companies were sent to the Ardennes to cut trees.

At first, the problem was the railway link between the Ardennes and the mines. A movement control group was brought from the UK to coordinate traffic. But then the German Ardennes offensive interrupted the supply, and four forestry companies had to fight as infantry. Efforts to find other sources of pit props in Belgium failed, so pit props were shipped from the UK. By the time they arrived in January, the crisis in the Ardennes had passed, and regular supply resumed. The goal of 2,000 tons of coal per day was soon met.

Other Supplies

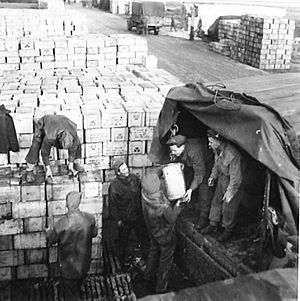

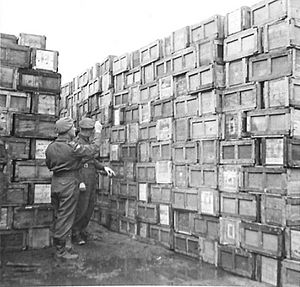

Until Antwerp opened, military stores arrived through Boulogne, Dieppe, and Ostend. Each port handled different types of stores, which made sorting easier. 58,000 tons of stores passed through these ports in the last three months of 1944. The 15th Advance Ordnance Depot (AOD) moved to Antwerp in September. It was joined by the 17th AOD. Stocking of the new depot began in November. It started issuing supplies to the Canadian First Army on 1 January 1945, and to the British Second Army ten days later. By 22 January, it served all supply lines. Until then, supplies came from the old Normandy area. The 15th/17th AOD grew to employ 14,500 people, mostly civilians, and occupied huge amounts of space. It stocked over 126,000 different items.

The 2nd Base Ammunition Depot (BAD) opened in Brussels in October 1944. Stocks there rose to 75,000 tons. The 17th BAD opened north of Antwerp later in the year, but V-weapon attacks made stocking it difficult. Even though a lot of ammunition was available, there were still shortages for field and medium artillery. In late October 1943, ammunition stocks seemed so high that production cuts were ordered. But by October 1944, the use of 25-pounder ammunition was exceeding production by 1.5 million rounds per month.

The War Office had to limit how much ammunition armies could use. This mostly affected the Eighth Army in Italy, where major operations were delayed. The 21st Army Group mostly avoided these shortages. On 7 November, the 21st Army Group limited usage to 15 rounds per gun per day for field artillery and 8 rounds per gun per day for medium artillery. But Montgomery said this only applied during quiet times, and that stocking the advanced base would continue until it had enough reserves.

The campaign caused a lot of wear and tear on vehicles. A major problem was found with the engines of 1,400 Austin K5 trucks. Early frosts and heavy military traffic created many potholes, damaging vehicle suspensions. Repair work was done in workshops in Brussels and Antwerp, which used civilian factories to increase their output. Civilian garages also helped with repairs.

So many armoured fighting vehicles broke down in September that replacement stocks were almost gone. By 27 September, no replacement tanks had arrived for three weeks. Armored units had only 70% of their equipment. Many repairable tanks were left along roadsides, waiting for recovery teams. It was arranged for 40 armored vehicles a day to be shipped to Boulogne in October. The next month, ships started arriving with tanks at Ostend. Deliveries were split between the two ports. Clearing the ports was a problem because Boulogne had no railway link, so tank transporters had to be used. By October, there were nine tank transporter companies. In December, a shortage of heavy truck tires meant four companies were taken off the road and used only in emergencies.

At Ostend, there was a rail link, but not enough railway wagons for tanks. Tank shipments used all available motor transport to forward ports. After Antwerp opened, shipments averaged 30 armored vehicles and 200-300 other vehicles per day. Two armored vehicle servicing units weren't enough, so a workshop from a disbanded armored brigade was used. In December, the ratio of tanks was changed to two Sherman Firefly tanks with the more powerful 17-pounder gun and one Sherman tank with the old 75 mm gun.

Two new armored vehicles arrived during the campaign: the American Landing Vehicle Tracked, used in the Scheldt operations, and the British Comet tank, issued in December. A return to using British tanks was prompted by a critical shortage of Sherman tanks in the US Army, which cut deliveries to the British Army. The re-equipment of the 29th Armoured Brigade was interrupted by the German Ardennes offensive. The brigade was quickly re-armed with its Shermans and sent to hold river crossings.

During the German Ardennes offensive, American depots stopped accepting shipments from Antwerp because they were threatened. But ships kept arriving. With no depots in the Antwerp area, American stores piled up on the quays. By Christmas, railway traffic had stopped. An emergency supply area was created near Lille for American traffic. The German offensive also raised fears for Brussels' water supply. The US Communications Zone requested an emergency delivery of 351 Sherman tanks. These were taken from depots, and their radios were replaced with US ones. Tank transporters moved 217 tanks, and the rest went by rail. US forces also borrowed 106 25-pounder guns, 78 artillery trailers, and 30 6-pounder anti-tank guns, along with ammunition.

Services

Civilian workers helped with many tasks, freeing military personnel for fighting. By the end of 1944, about 90,000 civilians worked for the 21st Army Group. Half of them worked for the Royal Engineers or in workshops. The Belgian government's Office of Mutual Aid (OMA) also helped. Similar agreements were made with France and the Netherlands.

| Date | France | Belgium | Netherlands | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 October 1944 | 9,322 | 9,073 | 739 | 19,134 |

| 1 November 1944 | 12,315 | 24,900 | 2,241 | 39,456 |

| 1 January 1945 | 14,477 | 64,753 | 11,489 | 90,719 |

Buying and producing items locally saved time and shipping space. Locally-produced items included 350,000 "duckbills" for tank tracks, which helped tanks move better on soft ground and snow. The OMA also set up a tire repair organization. Civilian workers were paid by their own governments. A free British Army meal was a big attraction. Giving out surplus military clothing and footwear helped overcome reluctance to work outdoors. But the biggest problem was the German V-weapons.

In addition to civilian labor, the Dutch and Belgian governments organized 24 Belgian and 12 Dutch labor units to help the Royal Pioneer Corps. The first six Belgian units joined the 21st Army Group in December. These units were equipped and clothed by the British Army.

Another source of labor was prisoners of war. By the end of December, the 21st Army Group had captured about 240,000 prisoners. Due to an agreement, prisoners were divided evenly between the US and UK. So, 100,000 prisoners were transferred to British control. However, the War Office limited the number of prisoners it would accept in the UK, leading to overcrowded prisoner of war camps in Europe.

Once it was clear that the advance into Germany would not be quick, and the 21st Army Group would stay in northern Belgium and the southern Netherlands for a while, preparations for winter began. This included warm clothing for troops, covered storage for supplies, and improving airfields for winter conditions. Huts were needed for 200,000 personnel, and 1,250,000 square feet (116,000 m²) of covered space for other purposes. Camps were set up for 100,000 refugees and prisoners of war. Large numbers of anti-aircraft units were based around Antwerp to protect the port.

No. 83 Group RAF alone needed nearly 700 huts for 12,000 personnel. Orders were placed for 1,000 Nissen huts in November and 5,000 per month after that. But coal and timber shortages made this difficult. Air bases were built and improved by the RAF. Getting them ready for winter involved repairing runways, building hangars and accommodation, and preparing hard surfaces for unloading aircraft. From December, a lot of effort went into keeping runways clear of snow and ice. The first Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation (FIDO) system outside the UK was installed at Épinoy. This used 90,000 liters of fuel each night.

Medical

It was important for hospitals not to be in tents during winter. Six general hospitals in Normandy were sent back to the UK until proper buildings could be found in the advanced base area. This was done by taking over existing civilian and German military hospitals, and converting schools and convents. Hospitals were built at Antwerp, Louvain (Leuven), Ostend, Bruges, and Dieppe. By 7 January, the 21st Army Group had 29,000 hospital beds.

Moving troops from tents to buildings led to more cases of colds and respiratory diseases. However, the rate of trench foot was low, with only 12 cases in November and 14 in December. In total, 206 cases of trench foot or frostbite were recorded among British and Canadian armies during the winter of 1944. This was much lower than in the American armies. This was because British soldiers were well-trained in foot care. The wet and cold climate of the British Isles and the experience of World War I made the British Army very aware of foot care. Soldiers were told not to stay on the front line for more than 48 hours in winter. Efforts were made to find warm and dry places for them when they were off duty. The British Battledress was warmer than the American uniform. Each soldier had a warm sleeveless leather jerkin. Extra pairs of socks were issued, and the boots allowed for two pairs of socks in cold weather. The boots were also more waterproof than American ones.

There was also an increase in cases of scabies and pediculosis (lice). Hospital admissions rose from 22.4 per 1,000 personnel in October to 28.0 in December.

Results and What Was Learned

| Advanced base | Channel ports | Normandy area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long tons | tonnes | long tons | tonnes | long tons | tonnes | |

| Supplies | 15,000 | 15,241 | 31,000 | 31,495 | 11,000 | 11,177 |

| Fuel | 79,000 | 80,269 | 27,000 | 27,432 | 26,000 | 26,417 |

| Ammunition | 32,000 | 32,512 | Nil | Nil | 25,000 | 25,401 |

With Antwerp open, the old supply area in Normandy was closed down. It still held about 300,000 tons of supplies, including 15 million rations, which were gradually used up. The last shipment of supplies to Normandy, except for fresh meat and vegetables, was in late October. Supplies still needed by the 21st Army Group were moved to the new advanced base around Antwerp. The rest were sent back to the War Office. Each day, 200 tons were moved by road and 200 tons by rail. By late November, a ship service moved 2,500 tons per day to Antwerp by sea.

Troops south of the Seine River continued to get supplies from Normandy. Those in France north of the Seine got supplies through the Channel ports. By the end of December, only 670 tons of ammunition remained in Normandy. The Mulberry harbor was damaged by autumn storms and closed in November. Work began to dismantle it.

Through American Lend-Lease (a program where the US supplied Allied nations), British logistics had access to huge resources. The system for using these resources effectively had been developed and improved in earlier campaigns in North Africa and Italy. The supply teams became very experienced and efficient. The main challenge was not if something could be done, but how quickly, and what the consequences would be. The supply system was strong and flexible. It could support both the fast advance through northern France and Belgium in September and the slower operations to capture Antwerp in October. The quick response of the supply system helped exploit successes and overcome difficulties. Military units were allowed to ask for whatever they needed without question. The dangers of having too many supplies were much less than the problems of a system that wasn't flexible enough.

On 15 January, after the German Ardennes offensive ended, the 21st Army Group began preparing for Operation Veritable. The 21st Army Group would push through the Reichswald forest, cross the Rhine, and advance into Germany. From a supply point of view, this would be much simpler than the breakout from Normandy in 1944. This was because of all the work done between September 1944 and the end of the year. A well-developed base was ready to support these operations. Railway lines extended into the front areas, supplies had been stored, and transport was available. This time, the 21st Army Group would not be held back by supply problems.

One lasting result of this operation was the use of British locomotives in Europe after the war. Many British-built locomotives were bought by French, Dutch, and Belgian state railways. The larger engines were heavily used, especially by the Dutch Nederlandse Spoorwegen. A WD Austerity 2-10-0 73755 Longmoor, which was the 1000th British-built steam locomotive sent to Europe to support the British Army, is now preserved at the Railway Museum in Utrecht.

Images for kids