Renminbi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Renminbi |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| ISO 4217 Code | CNY | ||

| User(s) | China (Mainland China) Wa State |

||

| Inflation | 2.5% (2017) | ||

| Method | CPI | ||

| Pegged with | Partially, to a basket of trade-weighted international currencies | ||

| Subunit | |||

| 1⁄10 | jiǎo (角) | ||

| 1⁄100 | fēn (分) | ||

| Symbol | ¥ | ||

| Nickname | kuài (块) | ||

| jiǎo (角) | máo (毛) | ||

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency does not have a morphological plural distinction. | ||

| Coins | |||

| Freq. used | ¥0.1, ¥0.5, ¥1 | ||

| Rarely used | ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05, ¥5, ¥10 | ||

| Banknotes | |||

| Freq. used | ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, ¥100 | ||

| Rarely used | ¥0.1, ¥0.5 | ||

| Printer | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation | ||

| Renminbi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Renminbi" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民币 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 人民幣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "People's Currency" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "circle" (ie. a coin) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The renminbi (Chinese: 人民币; pinyin: Rénmínbì; literally "People's Currency") is the official money of the People's Republic of China. Its symbol is ¥ and its international code is CNY. People often call it the Chinese Yuan or RMB. The People's Bank of China, which is like China's central bank, issues this currency. As of April 2022, it was the world's fifth most traded currency.

The yuan (Chinese: 元) is the main unit of the renminbi. One yuan is split into 10 jiao (Chinese: 角). Each jiao is then divided into 10 fen (Chinese: 分). When people talk about Chinese money, especially in other countries, they often just say "yuan."

Contents

Understanding the Value of Renminbi

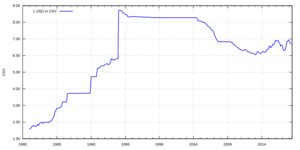

Until 2005, the value of the renminbi was tied to the US dollar. This means its value changed along with the dollar. As China's economy grew and became more involved in global trade, the renminbi's value was lowered. This made Chinese products cheaper for other countries to buy, helping Chinese businesses.

Over time, China started to let the renminbi's value change more freely. Since 2006, its value can move a little bit each day around a set price. This price is based on a mix of other important world currencies. The Chinese government has said it will continue to make the exchange rate more flexible. Because of these changes, the renminbi became the 8th most traded currency in 2013, then 5th by 2015.

On October 1, 2016, the renminbi became the first currency from a developing country to be part of the IMF's special currency basket. This basket holds currencies that the IMF uses as a reserve. The renminbi made up 10.9% of this basket at first.

| Current CNY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

Renminbi Names and Terms

The renminbi has different names depending on how formally you are speaking.

- Formal currency name: Renminbi (人民币). This means "people's currency."

- Formal name for 1 unit: Yuan (元 or 圆). This means "unit" or "circle."

- Formal name for 1/10 unit: Jiao (角). This means "corner."

- Formal name for 1/100 unit: Fen (分). This means "fraction" or "cent."

- Everyday name for 1 unit: Kuai (块). This means "piece."

- Everyday name for 1/10 unit: Mao (毛). This means "feather."

The international code for the renminbi is CNY. This comes from China's country code (CN) and the "Y" from "yuan." In Hong Kong, where renminbi is traded freely, they use the code CNH. This helps tell the difference between the free-floating rates and the rates set by China's central bank. The abbreviation RMB is also commonly used by banks.

The currency symbol for the yuan is ¥. To avoid confusion with the Japanese yen, people sometimes write RMB ¥10,000 or ¥10,000 RMB. In written Chinese, the character for yuan (Chinese: 元) or (Chinese: 圆) usually comes after the number instead of the symbol.

Think of it like this: "Renminbi" is the name of the currency system, while "yuan" is the name of the main unit, similar to how "sterling" is the currency system and "pound" is the unit in the United Kingdom. Jiao and fen are smaller units of the renminbi.

In daily conversations, Chinese people often use "kuai" instead of "yuan" and "mao" instead of "jiao." For example, ¥8.74 might be said as 八块七毛四 (bā kuài qī máo sì), but formally it would be 八元七角四分 (bā yuán qī jiǎo sì fēn).

Sometimes, the renminbi is called the "redback," which is a playful name like "greenback" for the US dollar.

History of Chinese Money

The renminbi was first introduced by the People's Bank of China in December 1948. This was about a year before the People's Republic of China was officially created. It was first issued only as paper money. One of the new government's main goals was to stop the very high inflation (when prices rise very quickly) that China had been facing. Once they achieved this, they changed the value in 1955 so that 1 new yuan was worth 10,000 old yuan.

As the Chinese Communist Party gained control of more areas during the Chinese Civil War, their bank started issuing a single currency in 1948. This currency was called by different names, but by June 1949, it was officially named "People's Currency," or "renminbi."

How China's Money Value Changed

From 1949 until the late 1970s, China's government kept the renminbi's value very high compared to Western money. This was part of a plan to help China's industries grow and rely less on imported goods. By keeping the currency strong, the government could buy imported machines and equipment for its factories at a lower cost.

By the mid-1990s, China slowly moved towards a system where the renminbi's value was set by how much people wanted to buy or sell it in the global market. This change happened over 15 years. It involved changing the official exchange rate and creating markets where foreign money could be exchanged.

One big step was making it easier for businesses to trade internationally. In 1979, the government allowed exporters to keep some of the foreign money they earned. They could also sell this extra foreign money through a state agency. Later, in the mid-1980s, the government allowed special markets called "swap centres" where foreign money could be exchanged.

Foreign Exchange Certificates (1980–1994)

When China started to open up to international trade and tourism, foreign visitors mainly used special money called Foreign exchange certificates (FECs). These were issued by the Bank of China between 1980 and 1994. Foreign money could be exchanged for FECs, and FECs were officially worth the same as renminbi.

Tourists used FECs to pay for hotels and special goods in "Friendship Stores." However, regular Chinese people couldn't use foreign money or shop in these stores. This led to an illegal market where people would offer more renminbi for FECs. In 1994, the renminbi's value was officially lowered, and FECs were stopped. Tourists then started using renminbi directly.

Modern Exchange Policy

In 1993, China decided to make big changes to how it managed foreign money. The goal was to have a flexible exchange rate and allow the renminbi to be fully convertible (meaning it could be freely exchanged for other currencies). This meant businesses could exchange foreign money they earned and buy foreign money when needed. Rules for foreign investments in China also became less strict, leading to more money flowing into the country.

As of 2013, you can exchange renminbi for everyday transactions (like buying goods), but not for large investments. China has been careful about making the renminbi fully convertible, partly because of concerns from the Asian financial crisis in 1998. They worry that too much money moving in and out quickly could harm their financial system. So, the currency still trades within a small range set by the government.

On November 30, 2015, the IMF decided to include the renminbi in its special basket of world currencies. This made the renminbi one of the main global currencies, alongside the dollar, the euro, sterling, and the yen. It officially joined the basket on October 1, 2016.

Digital Renminbi

In October 2019, China's central bank, the PBOC, announced that a digital reminbi would be released. This digital money, also called DCEP, could be used by tourists without needing a bank account. Some people think this is about more government control, while others believe it won't fully solve the challenges of making the renminbi a global currency because China still controls how much money can leave the country.

The PBOC has filed many patents related to this digital currency, showing their plans to use blockchain technology. These patents reveal ideas for how the digital currency would be issued, how banks would use it, and how it could be linked to existing bank accounts. Some patents even suggest that the supply of digital currency could be adjusted based on things like loan interest rates.

Experts in other countries, especially the U.S., are watching China's digital currency plans closely. Some worry that the U.S., which doesn't have a government-backed digital currency yet, might fall behind. However, many believe that the U.S. dollar will remain the main global currency due to America's strong economy and financial system.

In April 2020, it was reported that the digital currency was being tested in several Chinese cities. Some government workers even started receiving their salaries in digital currency. There were also talks of testing it during the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Interest Rates and Green Bonds

In May 2023, a new way to trade renminbi interest rate swaps was launched. In June 2023, the government of Hong Kong offered "green bonds" worth about US$6 billion. These bonds were in USD, EUR, and renminbi, showing a growing interest in environmentally friendly investments using the Chinese currency.

How Renminbi is Issued

As of 2019, renminbi banknotes come in denominations of ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (which are 1 and 5 jiao), ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, and ¥100. The ¥20 note was added in 1999, and the ¥50 and ¥100 notes were added in 1987. Coins are available from ¥0.01 to ¥1. This means some values exist as both coins and banknotes. Sometimes, special ¥5 or ¥10 coins are made for events, but they are mostly for collectors.

The value of each banknote is written in simplified Chinese and also in Arabic numerals. On the back of each banknote, the value and "People's Bank of China" are written in Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Zhuang languages, along with the Chinese Pinyin. Since the fourth series, the right front of the note also has a raised pattern for the value in Chinese Braille.

The smaller fen and jiao denominations are used less often now because prices have gone up. Coins smaller than ¥0.1 are rarely used. Chinese shops often round prices to the nearest yuan instead of using cents (like ¥9.99), so you might see ¥9 or ¥10 instead.

Coins

- In 1955, aluminium ¥0.01, ¥0.02, and ¥0.05 coins were first used. They show the national emblem on the front and the name and value surrounded by wheat on the back.

- In 1980, brass ¥0.1, ¥0.2, and ¥0.5 coins, and cupro-nickel ¥1 coins were added. The ¥0.1 and ¥0.2 coins were only made until 1981, and the last ¥0.5 and ¥1 coins were made in 1985. The jiao coins looked similar to the fen coins, while the yuan coin showed the Great Wall of China.

- In 1991, new, smaller coins were introduced: an aluminium ¥0.1, brass ¥0.5, and nickel-clad steel ¥1. These coins showed flowers on the front and the national emblem on the back. Production of the ¥0.01 and ¥0.02 coins stopped in 1991, and ¥0.05 coins stopped in 1994. However, the ¥0.01 coin started being issued again every year from 2005 onwards.

- New designs for the ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (now brass-plated steel), and ¥1 (nickel-plated steel) coins came out between 1999 and 2002. The ¥0.1 coin became much smaller. In 2005, its material changed from aluminium to stronger nickel-plated steel. An updated version of these coins was released in 2019. Now, all coins, including the ¥0.5, are made of nickel-plated steel, and the ¥1 coin is smaller.

Coins are more common in cities, especially for vending machines, while small banknotes are more popular in rural areas. Older fen and large jiao coins are still valid but not often seen.

Banknotes

China has issued five different series of renminbi banknotes:

- The first series was issued starting December 1, 1948. It included notes from ¥1 to ¥1,000, and later up to ¥50,000. A total of 62 different designs were made. These notes were officially removed from circulation between April and May 1955.

- The second series was introduced on March 1, 1955 (but dated 1953). Each note has "People's Bank of China" and the value written in Uyghur, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Zhuang languages on the back. This has been a feature on all later series. Denominations included ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05, ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥3, ¥5, and ¥10.

- The third series was introduced on April 15, 1962. The sizes and designs changed, but the colors for each value stayed the same. The second and third series notes were used at the same time for about 20 years. This series was gradually removed in the 1990s and fully recalled on July 1, 2000.

- The fourth series was introduced between 1987 and 1997. These notes were dated 1980, 1990, or 1996. They were removed from circulation on May 1, 2019. Denominations were ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50, and ¥100.

- The fifth series of renminbi banknotes and coins started being introduced in 1999. This series also has issue years like 2005, 2015, and 2019. As of 2019, it includes banknotes for ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, and ¥100. A big change in this series is that all banknotes feature the portrait of Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong. Earlier series showed different leaders, workers, and ethnic groups. New security features were added, the ¥2 note was stopped, and a new ¥20 note was introduced. A revised version of some coins and banknotes was issued on August 30, 2019. In November 2020, the ¥5 banknote got new printing technology to prevent fake money.

Special Commemorative Banknotes

China has also issued special banknotes to celebrate important events:

- In 1999, a red ¥50 note was issued to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the People's Republic of China. It shows Mao Zedong on the front.

- In 2000, an orange plastic note with a value of ¥100 was issued for the new millennium. It features a Chinese dragon on the front.

- For the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, a green ¥10 note was issued. It shows the Bird's Nest Stadium on the front.

- On November 26, 2015, a blue ¥100 note was issued to celebrate aerospace science and technology.

- To mark the 70th Anniversary of the renminbi's issuance, 120 million ¥50 banknotes were released on December 28, 2018.

- For the 2022 Winter Olympics, ¥20 commemorative banknotes (both paper and polymer) were issued in December 2021.

- For the 2024 Chinese New Year, ¥20 polymer banknotes were issued in January 2024.

Renminbi in Minority Regions

The renminbi yuan has different names in China's ethnic minority regions:

- In Inner Mongolia and other Mongol areas, a yuan is called a tugreg (Mongolian: ᠲᠦᠭᠦᠷᠢᠭ᠌, төгрөг). However, in the country of Mongolia, it's still called yuani (Mongolian: юань) to avoid confusion with their own money. One Chinese tugreg is divided into 100 mönggü (Mongolian: ᠮᠥᠩᠭᠦ, мөнгө}). In Mongolian, renminbi is called aradin jogos (Mongolian: ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠵᠣᠭᠣᠰ, ардын зоос).

- In Tibet and other Tibetan areas, a yuan is called a gor (Tibetan: སྒོར་, ZYPY: Gor). One gor is divided into 10 gorsur (Tibetan: སྒོར་ཟུར་, ZYPY: Gorsur) or 100 gar (Tibetan: སྐར་, ZYPY: gar). In Tibetan, renminbi is called mimangxogngü (Tibetan: མི་དམངས་ཤོག་དངུལ།, ZYPY: Mimang Xogngü).

- In the Uyghur region of Xinjiang, the renminbi is called Xelq puli (Uyghur: خەلق پۇلى).

How Renminbi is Made

The renminbi is produced by a state-owned company called China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation (CBPMC). This company has several factories across China that print banknotes and make coins. Banknote printing factories are in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu. Coin factories are in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Shenyang. Special high-quality paper for banknotes is made in Baoding and Kunshan. The Baoding factory is the largest in the world for making banknote materials. The People's Bank of China also has its own research division that develops new ways to make banknotes harder to fake.

The Renminbi in the Global Economy

For a long time, the renminbi's value was fixed to the U.S. dollar. For example, in 1980, ¥1.50 was equal to US$1. As China's economy opened up, the renminbi's value was lowered to make Chinese exports more competitive. By 1994, the exchange rate was ¥8.62 to US$1, which was its lowest point. From 1997 to 2005, it stayed at ¥8.27 to US$1.

On January 14, 2014, the renminbi reached a record high value of ¥6.0395 to the US dollar. China's leaders have been increasing the yuan's value to control rising prices. This also helps China move towards an economy where consumers buy more goods.

In August 2015, the People's Bank of China lowered the renminbi's value again. As of September 1, 2015, US$1 was worth ¥6.38.

No Longer Fixed to the US Dollar

On July 21, 2005, the renminbi was no longer officially fixed to the dollar. Its value immediately changed to ¥8.11 per dollar. However, when the global financial crisis hit in 2008, China unofficially re-tied its currency to the dollar.

On June 19, 2010, the People's Bank of China announced that they would allow the renminbi's exchange rate to be more flexible. This news was welcomed by world leaders. The PBoC said there would not be "large swings" in the currency's value. The renminbi then rose to its highest level in five years.

In August 2015, some financial experts believed that China had effectively re-tied the renminbi to the dollar again. They noticed that the currency stayed very steady despite big changes in China's stock market and economy.

Managed Floating Exchange Rate

Today, the renminbi uses a "managed floating exchange rate." This means its value is mostly set by how much people want to buy or sell it, but it also considers a mix of other foreign currencies. In July 2005, the daily trading price of the US dollar against the renminbi could change within a small range of 0.3% around a central price. This range was later increased to 0.5% in 2007, 1.0% in 2012, and 2% in 2014. China has said that the main currencies in this mix are the United States dollar, euro, Japanese yen, and South Korean won, with smaller amounts of sterling, Thai baht, roubles, Australian dollars, Canadian dollars, and Singaporean dollars.

On April 10, 2008, the renminbi traded at ¥6.9920 per US dollar, which was the first time in over ten years that a dollar bought less than ¥7.

Since January 2010, Chinese and non-Chinese citizens have a yearly limit of US$50,000 for currency exchange. To exchange money, you must go to a bank in person and show your passport or ID. These transactions are recorded. There are also daily limits on how much cash you can withdraw or buy. These strict rules help the government control the currency's value and prevent large amounts of money from flowing in or out too quickly.

International Use of Renminbi

Before 2009, the renminbi was not used much in international markets because the Chinese government had strict rules against sending it out of the country or using it for international deals. Most trade between Chinese and foreign companies was done in US dollars.

In June 2009, China started a trial program that allowed businesses in certain areas to trade directly in renminbi with partners in Hong Kong, Macau, and some Southeast Asian countries. This program was successful and expanded to more Chinese provinces and international partners.

To make the renminbi a more important international currency, China has made agreements with countries like Russia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Japan. These agreements allow trade with these countries to be paid directly in renminbi, without needing to convert to US dollars first. Australia and South Africa are expected to follow. In September 2023, the renminbi became the second most used currency in international trade, passing the euro.

Renminbi as a Reserve Currency

In July 2010, rules for holding renminbi in bank accounts and financial products became much more flexible. This made the yuan more attractive because it could offer better returns. Some national banks, like the Bank of Thailand, have expressed interest in holding renminbi as part of their foreign money reserves.

To meet the requirements of the IMF, China has loosened some of its strict controls over the currency.

Some countries, especially those with left-leaning governments, have started using the renminbi as an alternative to the US dollar for their reserves. For example, the Central Bank of Chile reported in 2011 that it held US$91 million worth of renminbi.

In Africa, the central banks of Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa either hold renminbi as a reserve currency or are planning to buy renminbi-denominated bonds. A report from August 2020 by the People's Bank of China stated that the renminbi is increasingly becoming an international reserve currency. In early 2020, the renminbi's share in global foreign exchange reserves reached a record high of 2.02%. By the end of 2019, the People's Bank of China had set up renminbi clearing banks in 25 countries and regions outside mainland China, making renminbi transactions more secure and cheaper.

Using Renminbi Outside Mainland China

The two special regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau, have their own currencies: the Hong Kong dollar and the Macanese pataca. So, while the renminbi is sometimes accepted there, it is not the official money. However, banks in Hong Kong allow people to have accounts in renminbi. Since July 2010, many banks worldwide have started offering individuals the option to hold renminbi deposits.

In Macau, renminbi-based credit cards can be issued, but they cannot be used in casinos.

Taiwan, which is governed by the Republic of China, has been cautious about the widespread use of the renminbi. They worry it could create an illegal economy and affect their independence. Tourists can bring up to ¥20,000 when visiting Taiwan, but they must exchange it for Taiwanese currency at special exchange points.

The renminbi is used in some of China's neighboring countries, like Pakistan, Mongolia, and northern Thailand. Cambodia accepts the renminbi as an official currency. Laos and Myanmar allow it in border areas and economic zones. Even though it's not official, Vietnam recognizes the exchange of renminbi for their currency, the đồng. In 2017, ¥215 billion was circulating in Indonesia. In 2018, Indonesia and China made an agreement to simplify business transactions using their own currencies. By 2020, about 10% of Indonesia's global trade was done in renminbi.

Since 2007, renminbi-denominated bonds (loans) have been issued outside mainland China. These are sometimes called "dim sum bonds." In April 2011, the first major stock offering in renminbi happened in Hong Kong. Beijing has allowed renminbi financial markets to grow in Hong Kong to help make the renminbi a more international currency.

Images for kids

-

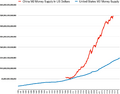

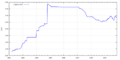

China M2 money supply (red) vis-à-vis USA M2 money supply (blue)

-

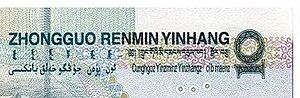

"People's Bank of China Ten Yuan" written in five different languages on the fifth series of the renminbi. From top to bottom and left to right: Mandarin pinyin, Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Zhuang languages.

-

A special edition designed for Inner Mongolia in the first series of the renminbi.

-

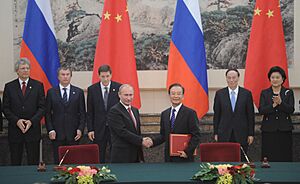

On November 24, 2010, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia's bilateral trade with China would be settled in roubles and yuan, instead of US dollars.

See also

In Spanish: Renminbi para niños

In Spanish: Renminbi para niños

- Chinese lunar coins

- Economy of China

- List of Chinese cash coins by inscription

- List of renminbi exchange rates

- Tibetan coins and currency