Diplomacy in the American Revolutionary War facts for kids

Diplomacy means how countries talk and work together. During the American Revolutionary War, the United States had to learn how to do this on its own. It was important for them to make friends and get help from other countries to win their independence.

How the Colonies Started Talking to Other Countries

Before the Revolutionary War, the American colonies let Britain handle all their dealings with other countries. They sent people to London to represent them. But as problems with Britain grew, the colonies started holding their own meetings, which led to the Continental Congress.

Committees of Correspondence: Getting Organized

Starting in 1772, colonies formed groups called Committees of Correspondence. These groups helped them share news and ideas about what Britain was doing. When Britain passed unfair laws like the Tea Act (1773) and the Intolerable Acts (1774), the colonies decided to act. The Continental Congress then created its own Committee of Correspondence, which later became the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1789. This was the start of America's own way of talking to other nations.

Britain Tries to Make Peace

Lord North's Offer (1775)

In February 1775, just before the war began, British Prime Minister Lord North tried to make peace. He offered a deal: if a colony helped with defense and supported the government, it wouldn't have to pay taxes, except for trade taxes. This offer was sent to individual colonies, hoping to divide them and stop the revolution. But it was "too little, too late." The war started in April 1775 at Lexington, and the Continental Congress quickly rejected Lord North's offer.

The Olive Branch Petition (1775)

Even after fighting started, some leaders in the Second Continental Congress, like John Dickinson, still hoped for peace. They sent the Olive Branch Petition to King George III in July 1775. This letter said the colonists were upset with the King's ministers, not the King himself, and asked for a peaceful solution. However, King George III refused to even read it.

Reaching Out to Canada

Letters to the Inhabitants of Canada

In 1774, Britain passed the Quebec Act, which gave French Canadians certain rights, including practicing Roman Catholicism. The Continental Congress wrote three letters (in 1774, 1775, and 1776) to the people of Quebec. They hoped to convince the French-speaking population to join the American cause. This effort mostly failed, and Quebec stayed with Britain. Only a small number of Canadian soldiers joined the American side.

Sending Envoys to France

Early Contacts and Aid

In December 1775, France, which was a rival of Britain, sent a secret messenger named Julien Alexandre Achard de Bonvouloir to talk with the Continental Congress. Early in 1776, Congress sent Silas Deane to France to ask for money and help. Deane worked with French officials like Vergennes and Beaumarchais to get weapons and supplies. He also convinced important European soldiers, like Lafayette and Baron von Steuben, to join the American fight.

Seeking Support from Other Nations

Arthur Lee was sent to Spain and Prussia to ask for their help. King Frederick the Great of Prussia didn't like the British, but he stayed neutral because of trade and fear of Austria. Spain was willing to fight Britain but didn't fully support the American cause because they worried about the idea of colonies becoming independent, which could affect their own empires in the Americas. In December 1776, Benjamin Franklin was sent to France as America's main representative, and he stayed there until 1785.

Early Friends of the United States

The Dutch Republic and Financial Help

In 1776, the United Provinces (today's Netherlands) were the first country to salute the Flag of the United States, which made Britain suspicious. The Dutch were important suppliers to the Americans. For example, many ships sailed from the island of Sint Eustatius carrying goods to America. When Britain started searching Dutch ships for weapons, the Dutch decided to stay neutral but prepared to defend their ships. Britain declared war on the Dutch in December 1780, starting the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. This war helped the Americans by making Britain fight on another front.

In 1782, John Adams arranged loans of $2 million from Dutch bankers for war supplies. On March 28, 1782, the Netherlands officially recognized American independence and signed a treaty of trade and friendship.

Morocco and Protection

Sultan Mohammed III of Morocco declared on December 20, 1777, that American merchant ships would be safe in Moroccan waters. This was a big deal for American trade. The Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship in 1786 became the oldest unbroken friendship treaty the U.S. has with any country.

France and a Strong Alliance

The Franco-American Alliance was a formal agreement between France and the United States, signed in May 1778. Benjamin Franklin's charm helped convince France to give more support. After the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, France officially allied with the U.S. against Britain. The treaty was signed on February 6, 1778. It was a defensive alliance, meaning both sides agreed to help each other if Britain attacked. Also, neither country would make peace with Britain until the United States' independence was recognized. France even considered invading Britain!

In March 1778, Conrad Alexandre Gérard de Rayneval sailed to America and became the first official French Minister to the United States.

British Attempts at Peace

Staten Island Peace Conference (1776)

After the British won the Battle of Long Island in September 1776, Admiral Lord Howe tried to end the war. He met with John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Edward Rutledge on Staten Island. Lord Howe wanted to talk to them as private citizens, but the Americans insisted on being recognized as official representatives of Congress. The Americans demanded that Britain recognize their independence, but Lord Howe said he didn't have the power to do that. So, the talks failed, and the British continued their military campaign.

Britain had offered pardons to rebels (with some exceptions), fair treatment for judges, and discussions about colonial complaints (except the Quebec Act). In return, they wanted a ceasefire, the Continental Congress to disband, and the old colonial assemblies to return. But the Americans wanted full independence.

Carlisle Peace Commission (1778)

After the British defeat at Saratoga in October 1777, and fearing France would recognize American independence, Lord North repealed the Tea Act and Massachusetts Government Act in February 1778. But it was too late.

A commission, led by Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle, was sent to negotiate with the Americans. They arrived in Philadelphia after news of the French alliance had already reached London. The commission offered many things, including:

- Stopping all fighting.

- Restoring trade and friendship.

- Allowing no British military force in America without Congress's permission.

- Helping America pay its debts.

- Allowing American representatives to have a voice in the British Parliament.

- Giving each state control over its own laws and government.

However, the British Army had left Philadelphia for New York, which made Congress even more determined to demand full independence. The British commission did not have the power to grant independence, so the talks failed.

Clinton–Arbuthnot Peace Declaration (1780)

In December 1780, the British commanders in North America, Sir Henry Clinton and Vice-Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot, offered pardons to rebels. But the Americans, known as Patriots, ignored this offer.

Native American Relations

The Treaty of Fort Pitt, signed on September 17, 1778, was the first written treaty between the new United States and any American Indian tribe, the Lenape (Delaware). It was signed in Pennsylvania and was meant to be an alliance. However, it was largely unsuccessful because most Native American tribes sided with the British during the war.

Relations with Spain

In 1777, Count of Floridablanca became Spain's Prime Minister. Spain's economy relied heavily on its colonies in the Americas. They worried that American independence might encourage their own colonies to seek freedom. Because of this, Spain often rejected John Jay's attempts to establish official diplomatic relations.

Even though Spain fought alongside the Americans against Britain, it did not officially recognize the United States' independence until near the end of the war. However, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, had been secretly helping the Americans since 1776.

In 1779, France and Spain signed a secret agreement called the Treaty of Aranjuez. Spain agreed to join France in the war against Britain to try and take back territories like Gibraltar, East Florida, West Florida, and Minorca. On June 21, 1779, Spain declared war on Britain. But Spain did not join the Franco-American alliance that guaranteed U.S. independence. Britain recognized U.S. independence in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but Spain was one of the last countries to do so.

Neutral Countries

Most of Europe officially stayed neutral during the American Revolutionary War. However, many people and leaders in countries like Sweden and Denmark supported the American Patriots. Britain struggled to find enough soldiers and only got help from a few small German states that hired out mercenaries to King George III.

|

enlightened despots for free trade |

|

The League of Armed Neutrality

The First League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance formed between 1780 and 1783 by three powerful Eastern European countries: Russia, Austria, and Prussia. These countries wanted to protect their trade ships from the British Royal Navy. Britain had a policy of stopping and searching neutral ships to look for French goods or weapons for the American rebels.

Catherine the Great of Russia started the League on March 11, 1780. She declared that neutral countries had the right to trade freely by sea with countries at war, as long as they weren't carrying weapons. She also said that blockades were only allowed for individual ports, not whole coastlines, and only if a British warship was actually there.

Denmark and Sweden joined Russia, and the three countries signed an agreement. They stayed out of the war but threatened to fight back if Britain searched their ships. When the Treaty of Paris (1783) ended the American Revolution in 1783, other countries like Austria, Prussia, the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic, Portugal, the Two Sicilies, and the Ottoman Empire had also joined the League.

The League helped trade with the U.S. during the war and promoted the idea of "freedom of the seas." Even though the British Navy was much larger, Britain didn't want to anger Russia, so they avoided bothering the League's ships. This alliance showed that diplomacy could be powerful even without direct fighting.

The Peace of Paris

The Peace of Paris was a group of treaties that officially ended the American Revolutionary War. In June 1781, the U.S. Congress appointed peace commissioners to talk with the British. On November 30, 1782, preliminary peace agreements were signed between the United States and Britain.

The Road to Peace Talks

News of the British surrender at Yorktown in November 1781 convinced Britain that it was time to change its strategy. Instead of fighting an "offensive" war in America, they decided to focus on defending against French and Spanish attacks in other parts of the world. This led them to start peace talks with the Americans.

Informal discussions had already been happening with Henry Laurens, an American envoy who had been captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London. The British negotiator sent to Paris was Richard Oswald, who had known Laurens before. His first talks with Benjamin Franklin even included a proposal for Britain to give Canada to the Americans, though this didn't happen.

Changes in British Government

In July 1782, the British government changed leaders, with Lord Shelburne taking over. This caused some political disagreements in Britain. Shelburne was clever in his negotiations. For example, he sent a letter to George Washington saying Britain accepted American independence without conditions. But he didn't give his negotiator, Richard Oswald, the same clear instructions right away.

Diplomatic Moves

Benjamin Franklin became ill, but John Jay learned about secret French talks with England and their position on fishing rights. Jay quickly sent a message to Shelburne, explaining why Britain should not be too influenced by France and Spain. Around September 24, the Americans heard that Britain had agreed to officially call the 13 colonies "United States" in the negotiations.

The Great Powers at War and Peace

The war started as a civil war between Britain and its colonies, but it grew into a global conflict. The American rebels needed outside help to succeed. Their forces struggled early on, with major cities occupied or blockaded. But with financial help from Dutch bankers and secret military aid from France, they kept fighting. French adventurers and European soldiers also joined the American cause.

In 1778, France officially recognized the United States with a trade treaty and a defensive alliance. This alliance said France would help the U.S. if Britain declared war on France for trading with America. It also guaranteed U.S. independence and its territory.

|

|

|

After the U.S. rejected the British Carlisle Commission, Britain became more aggressive towards any nation helping the U.S. This expanded the war worldwide. France declared war on Britain in 1778, and Spain joined France in 1779 with the secret Treaty of Aranjuez. Spain wanted to reclaim territories it had lost to Britain earlier, like Gibraltar and Florida.

This created problems for France's alliance with the U.S. The French-U.S. treaty guaranteed U.S. independence, but the French-Spanish treaty promised France would fight until Spain got Gibraltar, even if the U.S. gained independence sooner. This secret agreement was made without the U.S. knowing.

In 1780, neutral European powers formed the First League of Armed Neutrality to protect their trade from British interference. These additional conflicts strained Britain's resources for the war in America. Britain eventually decided to give up its American colonies. After this, Britain focused its resources on fighting France and Spain, leading to British naval victories around the world from 1782–1784. Britain was able to set the terms for separate peace treaties with the Americans, France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic.

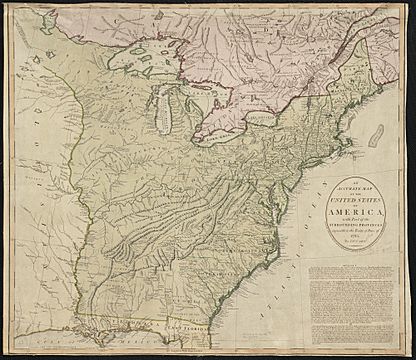

The Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the United States. The U.S. Congress ratified it on January 14, 1784, and King George III ratified it on April 9, 1784. The official documents were exchanged in Paris on May 12, 1784.

Other countries fighting Britain—France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic—also signed their own separate peace agreements with Britain. These treaties involved exchanging territories around the world.

Negotiating the Final Peace

From 1782 to 1784, many diplomats were in Paris, working on peace agreements for three different wars: the American Revolutionary War, the Anglo-French War, and the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. Diplomats from the First League of Armed Neutrality also shared ideas.

The conflict between Britain and its colonies had lasted over six years. About three years into the war, France and the U.S. agreed to consult each other before making peace with Britain. Then, France and Spain secretly agreed to fight until Spain got Gibraltar.

After the British defeat at Yorktown, British Prime Minister Shelburne wanted to separate the U.S. from France. He aimed to give America a large territory so it wouldn't need France's military help in the future. He also wanted to keep good trade relations with the new U.S. French Foreign Minister Vergennes, however, wanted to weaken the U.S. so it would always rely on France.

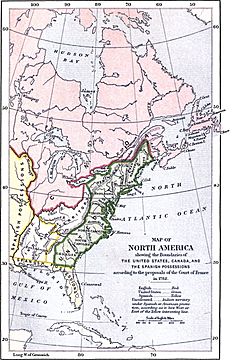

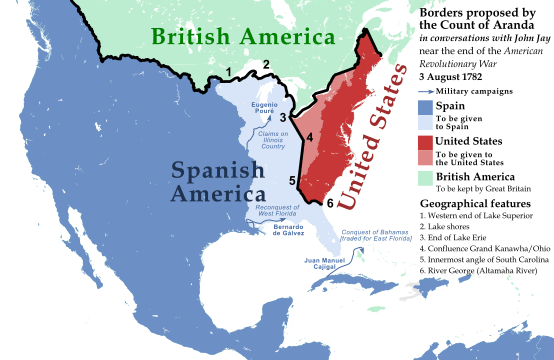

In Paris, the three main powers had different ideas for the U.S. territory:

- French Proposal: The French wanted to limit the U.S. to the Appalachian Mountains, similar to Britain's 1763 Proclamation Line.

- Spanish Proposal: The Spanish map allowed a bit more land west of the Appalachians for the U.S. But it also wanted Britain to give Georgia to Spain, which went against the French-American alliance.

- British Proposal: The British map, which was accepted by the U.S. Congress in April 1783, gave the U.S. territory stretching west to the middle of the Mississippi River.

- Maps proposed for US territory by France (1782), Spain (1782), Great Britain (1783)

-

French: readopt Royal Proclamation of 1763

-

British and US: "Conclusive" Treaty of Paris,

US west to Mississippi River midpoint

The U.S. Congress chose the British proposal because it offered the largest territory. They trusted Britain's promises more than the concerns from France and Spain, who had a secret treaty that the U.S. wasn't part of.

The Agreement is Signed

Based on preliminary agreements from November 30, 1782, and King George III's announcement of American independence in December 1782, the final Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783. It was signed at the Hôtel de York in Paris by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay for the United States, and David Hartley for Britain.

The American Congress ratified the treaty on January 14, 1784. British ratification happened on April 9, 1784, and the documents were exchanged in Paris on May 12, 1784. It took some time for the news to reach everyone in America due to slow communication.

On the same day, Britain also signed separate peace agreements with France, Spain, and the Netherlands.

- With Spain, Britain gave back East Florida and West Florida (though the northern border was unclear) and the island of Minorca. Spain returned the Bahama Islands, Grenada, and Montserrat to Britain.

- With France, the treaty mostly involved exchanging captured territories. France gained the island of Tobago and Senegal in Africa, and fishing rights off Newfoundland.

- With the Netherlands, Britain returned Dutch possessions in the East Indies in exchange for trade benefits.

Treaty Enforcement Challenges

After the war, the U.S. lost some privileges they had as British colonies, like protection from North African pirates in the Mediterranean.

Some American states ignored parts of the treaty. For example, they didn't always return property taken from Loyalists (Americans who supported Britain) and sometimes refused to pay debts to British creditors. The British also largely ignored the part of the treaty that said they should return runaway enslaved people who had escaped to British lines.

The geography of North America also caused problems. The treaty set a southern border for the U.S., but the British-Spanish agreement didn't clearly define Florida's northern border. Spain then used its control of Florida to block American access to the Mississippi River.

In the Great Lakes area, the British were slow to leave. They needed time to negotiate with Native Americans, who controlled the area and had been ignored in the treaty. Britain also held onto some forts as a bargaining chip to get money for Loyalist property. These issues were finally settled by the Jay Treaty in 1794. America's ability to deal with these problems improved greatly after the new Constitution was created in 1787.

What Happened Next

U.S. Ministers Abroad

In 1784, Britain allowed trade with the U.S. but restricted some American food exports to the Caribbean. This led to a shortage of gold in the U.S. American merchants began trading with China. In 1785, John Adams became the first U.S. minister to Great Britain, and Thomas Jefferson replaced Franklin as minister to France.

France

In 1793, a worldwide war broke out between Britain and France. George Washington declared that the United States would remain neutral. America stayed neutral until 1812, trading with both sides, though both sides sometimes caused problems for American ships.

Britain

In 1795, the U.S. signed the Jay Treaty with Britain. This treaty avoided another war and led to a decade of peaceful trade. It also settled boundary lines and debts. The British finally left the Western forts. The treaty was very controversial in the U.S. and played a big role in forming the first political parties.

Spain

The Treaty of Madrid (1795) set the borders between the U.S. and Spanish Florida and Louisiana. It also guaranteed American ships the right to use the Mississippi River. In 1797, the U.S. signed a peace treaty with Tripoli (a Barbary state in North Africa), but this was broken in 1801, leading to the First Barbary War. Also in 1797, the XYZ Affair happened, where French diplomats demanded bribes from American diplomats, leading to an undeclared naval war with France called the Quasi-War (1798-1800).

Ragusa

Ragusa (now in Croatia), a city with strong trade ties, was interested in trading with the United States. Its representative in Paris, Francesco Favi, learned that Italian merchants wanted to trade with Americans but worried about pirates. Ships from Ragusa had been delivering goods from American cities like Baltimore and New York to France since 1771. Ragusa and the United States made a trade agreement, allowing their ships free passage in each other's ports.

|

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |