North Atlantic right whale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Atlantic right whale |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mother and calf | |

|

|

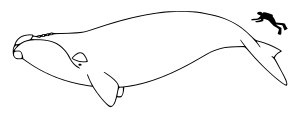

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Eubalaena

|

| Species: |

glacialis

|

|

|

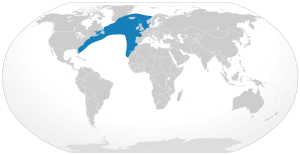

| Range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is a type of baleen whale. It is one of three right whale species. These whales were once easy targets for whalers. This was because they are calm, swim slowly, and stay close to the coast. They also have a lot of blubber, which made them float after being killed. This blubber produced a lot of whale oil.

Today, North Atlantic right whales are among the most endangered whales in the world. They are protected by laws in the U.S. and Canada. There are fewer than 366 of them left in the western North Atlantic. These whales travel between feeding areas in the Labrador Sea and birthing areas off Georgia and Florida. This area has a lot of ship traffic. In the eastern North Atlantic, there are very few left. Scientists think they might be almost gone there. The biggest dangers to these whales are being hit by ship strikes and getting caught in fishing gear. These two things cause almost half of all North Atlantic right whale deaths since 1970.

Physical Description

The North Atlantic right whale is also called the northern right whale or black right whale. You can easily tell it apart from other whales. It has no dorsal fin (the fin on its back). Its back is wide, and its flippers are short and paddle-like. It has a long, curved mouth that starts above its eye. These whales are dark gray to black. Some have white patches on their stomachs or throats.

Their head is very large, making up a quarter of their body length. Their tail is narrow compared to their wide fluke (tail fin). Their blowhole is V-shaped, which makes a heart-shaped blow when they breathe out.

The most special feature of right whales is their callosities. These are rough, white patches of skin on their heads. These patches are home to many tiny creatures called whale lice. These lice feed on the whale's skin. Scientists don't fully understand this relationship. Callosities are natural and are present on baby whales before they are born. However, many whale lice near the blowhole can mean the whale has been tangled in fishing gear or has other injuries.

Adult North Atlantic right whales are usually 13 to 16 meters (43 to 52 feet) long. They weigh about 40,000 to 70,000 kilograms (88,000 to 154,000 pounds). Females are usually larger than males. Up to 45% of a right whale's body weight is blubber. This blubber makes them float after they die.

Scientists believe these whales can live at least 70 years. Some related whale species have lived over 100 years. Currently, female North Atlantic right whales live about 45 years, and males live about 65 years.

Behavior

Surface Activities

North Atlantic right whales sometimes gather in groups called "SAGs" (Surface Active Groups). In these groups, a single female might be with several males. They seem less active than right whales in the southern hemisphere. This might be because there are so few of them left. Young whales tend to be more curious and playful than adults. These whales are also known to interact with other whales, like Humpback whales, and even Bottlenose dolphins.

Vocalization

North Atlantic right whales make sounds, and you can find recordings of them online. Scientists use special computer methods to find and identify their calls. This helps them study the whales.

Reproduction

North Atlantic right whales usually have their first baby when they are nine or ten years old. They are pregnant for about a year. The time between births has grown longer in recent years. It is now about three to six years. Baby whales are 4 to 4.5 meters (13 to 15 feet) long at birth. They weigh about 1,360 kilograms (3,000 pounds).

Feeding Habits

Right whales mostly eat tiny creatures called copepods. They also eat other small invertebrates like krill and tiny barnacles. They usually feed by slowly swimming through groups of these prey near the ocean surface. Other whales, like Sei whales and basking sharks, sometimes eat in the same areas. But there have been no fights seen between these species.

Taxonomy

The scientific name for this whale is Eubalaena glacialis. This name means "good, or true, whale of the ice."

In the 18th century, a whale called the "Swedenborg whale" was thought to be a North Atlantic right whale. But in 2013, DNA analysis of its bones showed it was actually a Bowhead whale.

Whaling History

Right whales were easy to hunt. They floated after being killed, so whalers could remove their blubber without bringing the whale onto the ship. They were also slow and stayed near the coast. This made them easy to catch, even with simple wooden boats and hand-held harpoons.

The Basques were the first to hunt these whales for business. They started whaling in the Bay of Biscay around the 11th century. At first, whales were hunted for their oil. Later, as food preservation improved, their meat became valuable. Basque whalers reached eastern Canada by 1530. By the mid-19th century, the North Atlantic right whale population was very low.

In the U.S., whalers from Nantucket and New Bedford caught many right whales. By 1750, the population was so low that it was not worth hunting them for business anymore.

Hunting right whales was banned globally in 1937 because their numbers were so low. This ban helped, but some illegal hunting continued for decades. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, it was discovered that the Soviet whaling fleet had secretly killed thousands of these whales from the 1950s to the 1970s, ignoring the ban.

Threats to Survival

From 1970 to 2006, humans caused almost half of the known deaths of North Atlantic right whales. Scientists predicted in 2001 that these whales could disappear within 200 years if human-caused deaths didn't stop. Because there are so few right whales and they don't have many babies, even a few deaths make a big difference. Preventing just two female deaths per year could help the population grow.

The main dangers to these whales are being hit by ships and getting tangled in fishing gear. These two factors stop the population from growing and recovering.

Where They Live

Before whaling, there might have been two groups of North Atlantic right whales, one in the eastern and one in the western North Atlantic. Some scientists also think there might have been one big group or even three smaller groups. Recent studies show that the eastern and western groups are more closely related than once thought. Climate change can also affect where these whales live.

Western Population

In spring, summer, and autumn, the western North Atlantic right whales feed from Massachusetts to Newfoundland. Popular feeding spots include the Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of Maine, and Cape Cod Bay. In winter, they travel south to Georgia and Florida to have their babies.

In 2010, there were at least 396 known individual whales in the western North Atlantic. This was up from 361 in 2005. Some whales also travel into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada. They are seen more often there since 1998. Some whales, including mothers and calves, also appear around Cape Breton Island. Their range can even reach Newfoundland and the Labrador Sea.

In early 2009, a record 39 new calves were born off Florida and Georgia. This was great news for the whales. However, 2012 was a very bad year for births, with only seven calves seen. This was much lower than the average of 20 calves per year. Scientists think a lack of food in 2010 might have caused fewer births in 2012.

In 2019, there were 411 of these whales left. The population has been growing by about 2.5% each year.

Scientists use planes and ships to find and track these whales. They identify individual whales, watch their behavior, and look for new calves. They also help whales that are tangled in fishing gear. You can find maps online that show where right whales are seen.

Eastern Population

In the eastern North Atlantic, there are very few right whales left, maybe only a dozen or so. We don't know much about where they live or how they travel. Scientists believe this group might be almost gone. The last time one was caught was in 1967.

Areas like Cintra Bay in the Western Sahara were once known places for these whales to have babies. But now, there are very few or no whales there. The Bay of Biscay also used to have many whales.

Recent Sightings

There have been a few sightings in the eastern Atlantic in recent decades. Some were near Iceland in 2003. These might be the last of the eastern group, or they could be whales that wandered from the western group. Some have been seen near Norway, Ireland, Scotland, and Spain. A mother and calf pair was seen at Cape St. Vincent in Portugal. A single whale was seen many times off Tenerife in the Canary Islands in 1995.

Right whales have also been seen rarely in the Mediterranean Sea. In 1991, a possible sighting was made off Sardinia.

| Year | Location | Type of record | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1805 | Hondarribia | Capture | |

| 1854 | San Sebastián | Capture | |

| 1878 | Getaria, Gipuzkoa | Capture | |

| 1893 | San Sebastián | Capture | |

| 1901 | Orio | Capture | |

| 1914 | Azores | Capture failed | |

| Prior to 1930 | Off the coast of Porto | Capture | |

| Between 1939 and 1949 | Capelinhos, Faial Island | Observation | |

| Between 1954 and 1957 | Mediterranean Sea | Observation | |

| January 1959 | Madeira | Capture (pregnant female) | |

| 1959–1966 | Cape Clear Island, Ireland | 5 separate observations | |

| 1964 | Off Cork, Ireland | Observation (uncertain being included in above records) |

|

| February 1967 | Madeira | ||

| August 1970 | Cape Clear Island, Ireland | Observation | |

| 1977 or 1978 (September) | Cape Finisterre, Galicia 43°00′N 10°30′W / 43.000°N 10.500°W | Observation | |

| June 1980 | Bay of Biscay | Observation (two whales) | |

| July–October 1980 | Between Harris and St Kilda, Scotland | Observation | |

| Second half of 20th century | Dutch coast | Bones found | |

| July 1987 | Mid Atlantic, off Iceland | Observation | |

| 1987 | Mid Atlantic, off Spain | Observation | |

| 1993 | Near A Coruña, Estaca de Bares, Galicia | Land-based observation (breaching individual) | |

| 1995 | Cape St. Vincent, Portugal | Observation (the only cow-calf pair in recent times) | |

| Channel between Tenerife and La Gomera | Observation | ||

| La Gomera | Two separate observations | ||

| Channel between Tenerife and Gran Canaria | Observation | ||

| Between Punta de Teno and Punta Scratch | Observation | ||

| Between June 1998 and January 1999 | La Gomera | Observation | |

| 1990s or 2000s | Off Donegal | Two observations | |

| May 2000 | Hatton Bank, off Ireland and Britain | Observation | |

| July 2000 | Off northern Shetland Islands | Observation (unclear if duplicate of above) | |

| 2012 | Lizard Point, Cornwall (possibly previously encountered by a kayaker in nearby areas) |

Possible observations |

- * A male accompanied a cow-calf and only the male fled

Whales from the Western Population Traveling East

Some whales seen in the eastern Atlantic have been confirmed to be from the western population. For example, a whale seen off Cape Cod in May 1999 was later seen in a fjord in Troms, Norway, in September 1999. This whale was named "Porter." He was seen back in Cape Cod in 2000, having traveled over 7,120 miles! This is the longest known journey for a right whale.

In 2009, a whale was seen off Pico Island, Azores. This was the first confirmed sighting there since 1888. This whale was identified as a female from the western Atlantic group and was nicknamed "Pico." These long journeys by individual whales might help scientists understand if the eastern Atlantic can be re-settled by whales in the future.

Possible Central Population

Some scientists think there might be a third group of right whales. This group might live near Iceland or Greenland in the north and near Bermuda or the Bahamas in the south. In 2003, a female right whale named "Hidalgo" was seen southwest of the Iceland coast. In 2009, right whales appeared near Greenland, though their origin wasn't confirmed.

Protecting the Whales

In the United States, the North Atlantic right whale is listed as "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act. This means it is at high risk of disappearing forever. It is also listed as "depleted" under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Globally, the Bonn Convention helps protect animals that migrate. It lists the North Atlantic right whale as a species threatened with extinction. This means countries must work hard to protect these whales, their homes, and their travel routes.

Another international agreement, CITES, also lists the North Atlantic right whale. This means it's against the law to buy or sell any parts of these whales (like oil, bones, or meat) across borders. This is only allowed for scientific research with special permission.

Whale Watching

You can watch North Atlantic right whales from land or on special boat tours along the east coast of North America. This includes areas from Canada down to Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary is a special place for watching these whales.

It can be hard to spot right whales because they don't stick out much from the water. So, all boaters and fishermen in areas where right whales live should keep a careful lookout. There's a rule that no one can get closer than 500 yards (457 meters) to a North Atlantic right whale. This rule applies to all boats, kayaks, surfers, and paddleboarders.

If you see a right whale, it's helpful to report it to researchers. In Florida, the Marine Resources Council has a group of volunteers who collect sighting information from the public.

Because these whales are so endangered, there are no regular whale watching tours for them in the eastern or middle Atlantic. Only off Iceland have right whales been seen during tours, but this is rare.

Images for kids

-

Disentanglement by NOAA staff off Jacksonville, Florida

-

Interacting with dolphins

See also

In Spanish: Ballena franca glacial para niños

In Spanish: Ballena franca glacial para niños