History of Christianity in Romania facts for kids

The history of Christianity in Romania tells us about how the Christian faith grew and changed in the land we now call Romania. It all started a very long time ago, even before Romania was a country!

Many Christians were killed for their faith in the Roman province of Lower Moesia around 300 AD. We know Christian communities existed because archaeologists have found signs of them in over a hundred places from the 3rd and 4th centuries. However, for a few centuries after that (from the 600s to the 900s), there isn't much information, so it seems Christianity might have become less common for a while.

Most people in Romania today belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church. This is different from most other countries where people speak languages similar to Romanian, as they usually follow the Catholic Church. Many basic Christian words in Romanian come from Latin, which shows how old Christianity is here. But Romanians also borrowed many words from South Slavic languages because they started using church services in Old Church Slavonic. The first Romanian translations of religious books appeared in the 1400s. The very first complete Bible in Romanian was printed in 1688.

The first official record of an Orthodox church leader among Romanians north of the Danube River is from 1234. Later, in the 1300s, when Wallachia and Moldavia became separate states, two main Orthodox church centers were set up. These were connected to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, a very important leader in the Orthodox world. Monasteries, which are homes for monks, grew a lot in Moldavia. This helped keep the Christian tradition strong in Eastern Europe.

In the areas west of the Carpathian Mountains, like Transylvania, the Orthodox Church was only allowed to exist for a long time. The Kingdom of Hungary had set up Roman Catholic churches there in the 1000s. When Transylvania became its own principality in the 1500s, four religions were officially recognized: Catholicism, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Unitarianism. Later, when the Habsburg Empire took over Transylvania, some Orthodox priests decided to join the Catholic Church in 1698. This created the Romanian Church United with Rome.

The Romanian Orthodox Church became fully independent in 1885. This happened years after Wallachia and Moldavia joined together to form Romania. Both the Orthodox Church and the Romanian Church United with Rome were called "national churches" in 1923. However, when the Communist government took power in 1948, they got rid of the Romanian Church United with Rome. The Orthodox Church was also put under government control. The Uniate Church was brought back when the Communist rule ended in 1989. Today, Romania's Constitution of Romania says that churches should be independent from the government.

Contents

Ancient Beliefs in Romania

Before Christianity arrived, people in the region had different beliefs. The Getae, an ancient group living near the Lower Danube, believed that the soul never died. They also worshipped a god named Zalmoxis. Sometimes, they even offered human sacrifice to communicate with him.

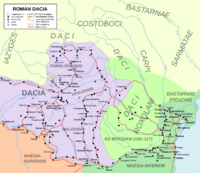

Modern Dobruja, the land between the Danube River and the Black Sea, became part of the Roman Empire in 46 AD. People there continued to worship Greek gods. Later, in 106 AD, other parts of Romania like Banat, Oltenia, and Transylvania became a Roman province called "Dacia Traiana". Many new people moved into Dacia, bringing their own gods from other parts of the Roman Empire. About 73% of all stone carvings from this time were dedicated to Graeco-Roman gods.

The Roman province of "Dacia Traiana" was given up by the Romans in the 270s. Dobruja became a separate Roman province called Scythia Minor in 297 AD.

How Christianity Came to Romanians

The first clear sign of an Orthodox church leader among Romanians north of the Danube River is from a letter by the Pope in 1234. In the 1300s, after Wallachia and Moldavia were founded, two main church centers were set up in these areas. They were connected to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Monasteries grew a lot in Moldavia, which helped keep the Christian faith strong in Eastern Europe.

In the areas west of the Carpathians, the Orthodox Church was only tolerated. Roman Catholic churches were set up there by the Kingdom of Hungary in the 1000s. When Transylvania became a principality in the 1500s, four religions were officially recognized: Calvinism, Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Unitarianism. After the Habsburg Empire took over, some local Orthodox priests joined the Catholic Church in 1698.

Many core religious words in Romanian come from Latin. For example, a boteza (to baptize), Paște (Easter), preot (priest), and cruce (cross). Some words, like biserică (church) and Dumnezeu (God), are unique to Romanian compared to other languages from Latin. This suggests that Christianity arrived very early in the region.

However, Romanian also adopted many Slavic religious words. Examples include duh (spirit), iad (hell), rai (paradise), and popă (priest). Some Greek and Latin terms, like călugar (monk), also came through Slavic languages. A few religious words even came from Hungarian, like mântuire (salvation).

There are different ideas about how Christianity started in Romania. Some historians believe it spread as the Romanian people were forming, with Romans and native Dacians mixing. This process of becoming Roman and Christian took several centuries. Other historians think that the ancestors of Romanians became Christian south of the Danube River, after Christianity became legal in the Roman Empire in 313 AD. They might have adopted Slavic church services there before moving to modern Romania later.

Christianity in Roman Times

Christian communities in Romania existed as early as the 200s AD. Some stories say that Jesus's teachings first reached "Scythia" through Saint Andrew. If "Scythia" means Scythia Minor (part of modern Romania), then Christianity here could have started with an apostle.

Whether Christian communities existed in Dacia Traiana is debated. Some Christian objects from the 200s have been found there, before the Romans left. These include vessels with crosses, fish, and other Christian symbols. A gem showing the Good Shepherd was found at Potaissa. Some pagan monuments were later changed to include Christian symbols. A ring found with an inscription about "Jupiter's scourge against Christians" might be linked to the persecution of Christians in the 200s.

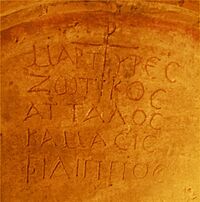

In Scythia Minor, many Christians were killed for their faith around 300 AD during a time of persecution. The remains of four martyrs were found in a tomb at Niculițel, with their names written in Greek. Many churches, called basilicas, were built between the 300s and 500s in the main towns of the province. The earliest church north of the Lower Danube was built at Sucidava (now Celei). Burial chambers with painted walls showing quotes from Psalms were found in other towns.

Church leaders from Scythia Minor were involved in important discussions at the early Church Councils. Saint Bretanion defended the Orthodox faith in the 360s. The main bishop of the province, called a metropolitan, was in Tomis (modern Constanța). The last metropolitan was mentioned in the 500s, before the region was attacked by the Avars and Sclavenes. Important Christian writers like John Cassian and Dionysius Exiguus lived in Scythia Minor and helped spread Christianity.

Early Middle Ages

Christianity Spreads

Most Christian items found in the former Roman Dacia from the 300s to 500s were brought from the Roman Empire. One of the first Christian objects found in Transylvania was a bronze inscription at Biertan. Some graves from the 300s were arranged in a Christian way. Clay lamps with crosses from the 400s and 500s were also found.

Christianity spread in former Roman Dacia when Constantine the Great reconquered parts of it. Many early Christian finds, especially from the 300s, were discovered at the Roman fortress of Sucidava (Olt county). Other objects with Christian symbols were found in places like Alba Iulia and Cluj-Napoca.

Around 350 AD, the "Taifali, Victuali, and Tervingi" ruled Dacia Traiana. Christian teachings began among the Tervingi (Western Goths) in the 200s. For example, Ulfilas, who became a bishop in 341, had ancestors captured in Capadocia. During persecutions, Ulfilas was sent to Moesia, where he continued to preach in Greek, Latin, and Gothic. Many believers, like Sabbas the Goth, were killed between 369 and 372.

After the Hunnic Empire fell in 454, the Gepids ruled Dacia. A gold ring with crosses from a 400s grave at Apahida was found. The Gepid kingdom was destroyed by the Avars in 567–568.

The rule of Justinian I (527-565) saw the Eastern Roman Empire expand. He rebuilt fortresses along the Danube, like Drobeta and Sucidava. This showed that Roman towns were on both sides of the river.

Christians were also found among the "barbarians." Some Romans among the Sclavenes might have been Christians. Christian symbols appeared in places south and east of the Carpathians in the 560s. Molds for making crosses were found in these areas starting in the 500s.

East and South of the Carpathians

In the 700s, cemeteries south and east of the Carpathians show that people often burned their dead. By the early 1000s, burying the dead became more common.

From the 800s to 1000s, over 52 Christian items were found east of the Carpathians. Many were made locally. These finds suggest that people practiced Christian burial before the Bulgarians and Slavs became Christian.

The areas between the Lower Danube and the Carpathians became part of the First Bulgarian Empire by the early 800s. Boris I was the first Bulgarian ruler to accept Christianity in 863. He allowed Eastern Orthodox clergy into his country in 864. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church started using the Bulgarian alphabet in 893. An inscription from 943 in Mircea Vodă, Constanța is the earliest example of the Cyrillic script in Romania.

The Byzantine Empire conquered the First Bulgarian Empire around 1000. The main church center in Scythia Minor was brought back in Constanța. Later, a new church center was set up in Dristra (now Silistra, Bulgaria) in the 1040s.

In 1165, a traveler described the Vlachs (Romanians) in Greece as "false Christians." However, two brothers, Peter and Asen, built a church to start a rebellion against the Byzantine Empire. They created the Second Bulgarian Empire. The head of their church was called "Primate of the Bulgarians and the Vlachs" in 1204.

Catholic missionaries worked among the Cumans who controlled lands north of the Lower Danube from the 1070s. A new Catholic church area was set up in 1228. A letter from Pope Gregory IX in 1234 said that many people in this area were Orthodox Romanians. They were even converting Hungarian and Saxon settlers to their faith. The Pope complained that these Romanians were not following the Roman Church.

Inside the Carpathian Mountains

Christian objects disappeared in Transylvania after the 600s. Most cemeteries had cremation graves. But some burial graves from the late 800s or early 900s were found. The Hungarians invaded this area around 896.

A Hungarian leader, the gyula, became Christian in Constantinople around 952. He brought a Greek bishop back to Hungary. Crosses from this time have been found in Transylvania. A Greek monastery was founded at Cenad around 1002.

Later, under Stephen I of Hungary, who was baptized in the Latin rite, Transylvania became part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Stephen I introduced the tithe, a church tax. The first three Roman Catholic churches in Romania were set up then.

Large cemeteries grew around churches. The first Benedictine monastery in Transylvania was founded in the late 1000s. New monasteries were built in the following centuries. The differences between the Eastern and Western Churches also grew in the 1000s.

Middle Ages

Orthodox Church in Transylvania

Even though a church council in 1279 tried to stop Orthodox churches from being built, many were constructed from the late 1200s onwards. These churches were mostly made of wood, but some wealthy landowners built stone churches. Many were painted with pictures of the church founders.

By the late 1300s, local Orthodox churches were often under the control of the main church leaders in Wallachia and Moldavia. Orthodox monasteries in Romania, like Șcheii Brașovului, became important places for writing in Slavonic. The Bible was first translated into Romanian by monks in Maramureș during the 1400s.

In 1356, Pope Innocent VI ordered a crusade against "heretics" in Transylvania, Bosnia, and Slavonia.

Treatment of Orthodox Christians got worse under Louis I of Hungary. In 1366, he ordered the arrest of Orthodox priests. He also said that only those who followed the Roman Catholic faith could own property in certain areas. However, not many people converted. A Franciscan friar complained in 1379 that "stupid people" didn't like the idea of converting Slavs and Romanians. Both Romanians and Catholic landowners opposed this command. Romanian chapels and stone churches on Catholic lands were often mentioned in documents from the late 1300s.

A special investigator sent by the Pope also took strong actions against "schismatics" (Orthodox Christians) in 1436. After the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches tried to unite at the Council of Florence in 1439, the local Romanian Church was considered united with Rome. Those who opposed this union were imprisoned.

Even though kings only pushed for conversion in southern borderlands, many Romanian noblemen became Catholic in the 1400s. In the late 1500s, Transylvanian authorities tried to convert Romanians to Calvinism. Priests who didn't convert were ordered to leave in 1566. The Orthodox church leadership was only brought back in 1571.

Orthodox Church in Moldavia and Wallachia

An Italian writer wrongly called Romanians "pagans" in the early 1300s. But Basarab I, the ruler who made Wallachia independent, was called "schismatic" (Orthodox) in a document from 1332. The main church center of Wallachia was set up in 1359. Later, a second center was created, but by 1403, there was only one again. The local Church was reorganized around 1500.

Moldavia also became independent under Bogdan I (1359). It was first under a church leader in Ukraine. The Ecumenical Patriarch set up a separate church center for Moldavia in 1394. The conflict was resolved in 1401 when a member of the princely family became the metropolitan.

From the late 1300s, Romanian princes supported monasteries on Mount Athos in Greece. Monks escaping the Ottomans founded the earliest monastery in Moldavia at Neamț in 1407. From the 1400s, the four Eastern patriarchs and other monasteries in the Ottoman Empire also received land and income from the two principalities.

Many monasteries, like Cozia in Wallachia and Bistrița in Moldavia, became important centers for Slavonic writing. The first local histories were also written by monks. Religious books in Old Church Slavonic were printed in Târgoviște after 1508. Wallachia became a leading center for the Orthodox world. The cathedral of Curtea de Argeș was consecrated in 1517 with important church leaders present. The painted monasteries of Moldavia are still famous today.

Monasteries owned a lot of land, making them powerful. Many also owned Romani and Tatar slaves. Monasteries had tax benefits, but rulers sometimes tried to take their wealth.

Wallachia and Moldavia remained independent, but their princes had to pay a yearly tax to the Ottoman sultans starting in the 1400s. Dobruja was taken by the Ottoman Empire in 1417. These areas were under the control of Orthodox church leaders for centuries.

Other Religions in the Middle Ages

The Catholic church area of Cumania was destroyed during the Mongol invasion of 1241–1242. After this, Franciscan missionaries continued to work in the East. In the 1300s and 1400s, new Catholic churches were set up east and south of the Carpathians, mainly because of Hungarian and Saxon settlers. Romanians even complained to the Pope in 1374, asking for a Romanian-speaking bishop. Alexander the Good of Moldavia also founded an Armenian bishopric in Suceava in 1401. However, in Moldavia, many Catholics were forced to become Orthodox in the mid-1500s.

In the Kingdom of Hungary, Catholic parish organization fully developed in the 1300s and 1400s. In the 1330s, about 40% of villages in the kingdom had Catholic parishes. In modern Romania, 954 out of 2100-2200 settlements had a Catholic church. The power of the Catholic Church in Transylvania was weakened by authorities in the late 1500s. Its vast lands were taken in 1542. The Catholic Church lost its own high-ranking leaders and became controlled by a state with Protestant rulers. However, some noblemen, including parts of the powerful Báthory family, remained Catholic.

The Reformation

The Hussite movement for religious reform started in Transylvania in the 1430s. Many Hussites moved to Moldavia, where they were not persecuted.

The first signs of Lutheran teachings in Transylvania appeared in 1524. The Transylvanian Saxons decided to adopt the Lutheran faith in 1544. City leaders also tried to influence Orthodox church services. A Romanian Catechism (a book of Christian teachings) was published in 1543, and a Romanian translation of the four Gospels in 1560.

Calvinist preachers started working in Oradea in the early 1550s. In 1564, the Diet (assembly) recognized two separate Protestant churches. The government also pressured Romanians to change their faith. In 1566, it was decided that a Romanian Calvinist bishop would be their only religious leader.

In the 1560s, some Hungarian preachers questioned the idea of the Trinity. Within ten years, Cluj became the center of the Unitarian movement. In 1568, the Diet of Turda recognized four "received religions" and allowed ministers to teach based on their own understanding of Christianity. Even though new religious changes were banned in 1572, many Székelys became Sabbatarians in the 1580s.

Giving up old traditions after the Reformation was very slow in Transylvania. While some images were removed from churches, sacred items were kept. Protestant churches also continued to observe holidays and fasting periods strictly.

Early Modern and Modern Times

Orthodox Church in Moldavia, Wallachia, and Romania

Using Romanian in church services began in Wallachia under Matei Basarab (1632–1654) and in Moldavia under Vasile Lupu (1634–1652). In 1642, a meeting of Orthodox leaders in Iași adopted the "Orthodox Confession of Faith" to reject Calvinist ideas. The first complete Romanian "Book of Prayer" was published in 1679. A group of scholars also finished the Romanian translation of the Bible in 1688.

The two principalities faced heavy Ottoman control during the "Phanariot century" (1711–1821). The late 1700s brought a spiritual rebirth, led by Paisius Velichkovsky. This led to a return of a special prayer style in Moldavian monasteries. In this period, Romanian religious culture benefited from new translations of ancient Christian writings. In the early 1800s, schools for religious studies were set up in both principalities.

When the Russian Empire took Bessarabia in 1812, a new archbishopric was created there, reporting to the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian authorities soon stopped its archbishop from having any ties with the Orthodox Church in the Romanian principalities.

Romanian society developed quickly after native princes returned in 1821. For example, Romani slaves owned by monasteries were freed in Moldavia in 1844 and in Wallachia in 1847. The two principalities united under Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1859–1866) and became Romania in 1862. During his rule, monastery lands were taken over by the state. He also supported using Romanian in church services and replaced the Cyrillic alphabet with the Romanian alphabet. In 1860, the first Orthodox Theology Faculty was founded at the University of Iași.

The Orthodox churches of the former principalities, the Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia and the Metropolitan of Moldavia, joined to form the Romanian Orthodox Church. In 1864, the Romanian Orthodox Church declared itself independent. However, the Ecumenical Patriarch said this was against church rules. From then on, all church appointments and decisions needed state approval. The Metropolitan of Wallachia became the head of the Romanian Orthodox Church in 1865. The 1866 Constitution of Romania recognized the Orthodox Church as the main religion. A law in 1872 declared the church "autocephalous" (self-governing). After long talks, the Patriarchate of Constantinople finally recognized the Metropolis of Romania in 1885.

After the Romanian War of Independence, Dobruja became part of Romania in 1878. Most people there were Muslim, but many Romanians soon moved in. The region also had Russian Old Believers called Lipovans from the late 1600s.

The Great Powers recognized Romania's independence in 1880. This happened after Romania's constitution was changed to allow non-Christians to become citizens. To celebrate independence, the Orthodox church leaders performed a special ceremony in 1882. This was a privilege usually only for ecumenical patriarchs. This new conflict with the patriarch delayed the official recognition of the Romanian Orthodox Church's independence for three years, until 1885.

Orthodox Church in Transylvania and the Habsburg Empire

In the 1500s, the Calvinist princes of Transylvania insisted that Orthodox priests obey Calvinist leaders. For example, when an Orthodox meeting tried to set church rules, Gabriel Bethlen (1613–1630) removed the local metropolitan. By forcing the use of Romanian instead of Old Church Slavonic in church services, the authorities also helped Romanians develop their national identity. Local Orthodox believers were left without their own religious leader after Transylvania joined the Habsburg Empire. This happened when a church meeting led by the metropolitan declared the union with Rome in 1698.

The first effort to bring back the Orthodox Church started in 1744. A monk named Sofronie organized Romanian peasants to ask for a Serbian Orthodox bishop in 1759–1760. In 1761, the government allowed an Orthodox church area to be set up in Sibiu. It was under the control of the Serbian Metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci.

In 1848, Andrei Șaguna became the bishop of Sibiu. He worked to free the local Orthodox Church from Serbian control. He succeeded in 1864, when a separate Orthodox Church with its main center in Sibiu was established with government approval. In the late 1800s, this church oversaw four high schools and over 2,700 elementary schools. The Orthodox Church in Bukovina also became independent of the Serbian Metropolitan in 1873. A Faculty of Orthodox Theology was founded at the University of Cernăuți in 1875. However, many Romanian priests were sent away or imprisoned for supporting the union of Romanian lands after Romania declared war on Austria–Hungary in 1916.

Romanian Church United with Rome

After Transylvania became part of the Habsburg Empire, the new Catholic rulers tried to get Romanian support. They wanted to strengthen their control over the principality, which was mostly Protestant. For Romanians, joining the Catholic Church gave them hope that the government would help them in their conflicts with local authorities.

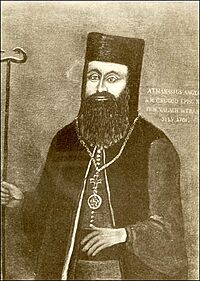

The union of the local Romanian Orthodox Church with Rome was declared in Alba Iulia in 1698. This happened after years of talks, led by Metropolitan Atanasie Anghel and thirty-eight archpriests. This union was based on four points, including recognizing the Pope as the head of the Church. Atanasie Anghel lost his title of metropolitan and was re-ordained as a bishop under the archbishop of Esztergom in 1701.

The Orthodox world saw this union with Rome as a betrayal. Metropolitan Theodosie of Wallachia called Atanasie Anghel "the new Judas". Since many local Romanians opposed the union, it also caused disagreements among them.

Uniate Romanians played a leading role in fighting for Romanians' political rights in Transylvania for the next century. Bishop Inocențiu Micu-Klein asked many times for Romanians to be recognized as the fourth "political nation" in the province. The Uniate bishopric in Transylvania was raised to the rank of a Metropolitan See and became independent in 1855.

Other Religions in Modern Times

Calvinism was popular in Transylvania during the 1600s. Over sixty Unitarian ministers were forced out of their churches in the 1620s because of Calvinist leaders. Even though laws against Sabbatarians were passed, Sabbatarian communities survived in some villages.

The religious life of Saxon communities was marked by differences from Calvinism and more worship services. Traditional Lutheranism remained more popular than Crypto-Calvinism. The Catholic Church's assets were managed by "Catholic Estates," a group of lay people and priests. A report from around 1638 showed many Catholic villages without priests.

Transylvania, after joining the Habsburg Empire, was governed by rules that confirmed the special status of the four "received religions." However, the new government favored the Roman Catholic Church. Between 1711 and 1750, the government made sure Catholics got preference for high positions. The Roman Catholic Church's top status was not weakened under Joseph II (1780–1790), even though he issued a law allowing more tolerance in 1781. Catholics who wanted to convert to other religions still had to undergo instruction. The equal status of the Churches was not declared until Transylvania united with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1868.

In the Kingdom of Romania, a new Roman Catholic archbishopric was set up in Bucharest in 1883. Among new Protestant groups, the first Baptist church was formed in 1856, and the Seventh-day Adventists first appeared in Pitești in 1870.

Greater Romania

After World War I, Romanians in many regions voted to join the Kingdom of Romania. The new borders were recognized by international treaties in 1919–1920. So, Romania, which had been quite uniform, now had many different religious and ethnic groups. According to the 1930 census, 72% of its citizens were Orthodox, 7.9% Greek Catholic, 6.8% Lutheran, 3.9% Roman Catholic, and 2% Reformed.

The constitution adopted in 1923 said that different religious beliefs did not stop people from having political rights. It also recognized two national churches: the Romanian Orthodox Church as the main one, and the Romanian Church United with Rome as having "priority over other denominations." The 1928 Law of Cults gave full recognition to seven more religions, including the Roman Catholic, Armenian, Reformed, Lutheran, and Unitarian Churches.

All Orthodox church leaders in the larger kingdom became members of the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church in 1919. New Orthodox bishoprics were set up. The head of the church was raised to the rank of patriarch in 1925. Orthodox church art grew a lot during this time, with new churches built, especially in Transylvania. The 1920s also saw new Orthodox movements, like the "Lord's Army" founded in 1923. Some Orthodox groups who refused to use the Gregorian calendar formed a separate church.

During this period, protecting the cultural heritage of ethnic minorities became a main job for traditional Protestant churches. The Reformed Church became closely linked with the local Hungarian community. The Lutheran Church saw itself as carrying on Transylvanian Saxon culture. Among new Protestant groups, the Pentecostal movement was made illegal in 1923. Strong disagreements between Baptist and Orthodox communities led to the temporary closing of all Baptist churches in 1938.

Communist Rule

After World War II, Romania lost Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union. So, the Orthodox churches in those areas came under the Russian Orthodox Church. In Romania, the Communist Party used similar methods as in other Eastern European countries. The Communist Party first supported a coalition government, but soon pushed out all other parties.

The 1948 Law on Religious Denominations officially said there was freedom of religion. But it also had rules that forced priests and believers to follow the constitution, national security, and public order. For example, priests who spoke against communism could lose their state salaries. The new law recognized fourteen religions, but the Romanian Church United with Rome was abolished.

Even though the Orthodox church was completely controlled by the state, over 1,700 Orthodox priests were arrested between 1945 and 1964. The Orthodox theologian Dumitru Stăniloae was imprisoned between 1958 and 1964. The first Romanian saints were officially recognized between 1950 and 1955.

Some other religions faced an even harder time. For example, four of the five arrested Uniate bishops died in prison. Religious movements that disagreed with the government became very active between 1975 and 1983. For instance, the Orthodox priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa spent many years in prison for his sermons. The crisis that led to the fall of the regime in 1989 also started with the strong resistance of the Reformed pastor László Tőkés, whom the authorities wanted to silence.

Romania Since 1989

The Communist government ended suddenly on December 22, 1989. The poet Mircea Dinescu, who was the first to speak on free Romanian television, started by saying: "God has turned his face toward Romania once again." The new constitution of Romania, adopted in 1992, guarantees freedom of thought, opinion, and religious beliefs, as long as they are shown with tolerance and mutual respect. Eighteen groups are now recognized as religious denominations in the country. Over 350 other religious groups have also registered, but they don't have the right to build churches or perform baptisms, marriages, or burials.

Since the fall of Communism, about fourteen new Orthodox theology schools have opened. Orthodox monasteries have been reopened, and new ones have even been founded. The Holy Synod has recognized new saints, including Stephen the Great of Moldavia (1457–1504). They also declared the second Sunday after Pentecost the "Sunday of the Romanian Saints."

The Greek Catholic church leadership was fully restored in 1990. The four Roman Catholic churches in Transylvania, mostly with Hungarian-speaking members, hoped to join into a separate church province. But only Alba Iulia was raised to an archbishopric and placed directly under the Pope in 1992. After many Transylvanian Saxons moved to Germany, only about 30,000 members of the German Lutheran Church remained in Romania by the end of 1991. According to the 2002 census, 86.7% of Romania's population was Orthodox, 4.7% Roman Catholic, 3.2% Reformed, 1.5% Pentecostal, 0.9% Greek Catholic, and 0.6% Baptist.

|