History of Ecuador facts for kids

The History of Ecuador tells the story of people living in this land for about 8,000 years. Many different cultures have shaped the country we know today as the Republic of Ecuador.

For thousands of years, native tribes lived here. Then, in the early 1400s, the powerful Inca Empire took over. But the Incas didn't rule for long. In the early 1500s, Spanish explorers led by Francisco Pizarro conquered them.

Ecuador became part of Spain's huge Viceroyalty of Peru. Later, in 1720, it joined the Viceroyalty of New Granada. A fight for independence began in 1812 but was quickly stopped. The real struggle started in 1820 in Guayaquil. Famous leaders like Simon Bolivar and San Martin met there. Ecuador first became part of a larger country called Republic of Gran Colombia, then became fully independent in 1830.

After independence, Ecuador faced civil wars and was often led by strong military leaders called caudillos. In the 1900s and 2000s, Ecuador continued to work towards being a stable country, both economically and politically.

Contents

Ancient Ecuador: Before the Spanish Arrived

Before the Incas, people in Ecuador lived in family groups that formed large tribes. Some tribes even joined together to create powerful groups, like the Confederation of Quito. But none of these groups could stop the mighty Tawantinsuyu (the Inca Empire). The Inca invasion in the 1500s was very difficult and bloody. However, once the Incas, led by Huayna Capac, took over the Quito area, they set up a big government and started to settle the region.

We can divide the time before the Spanish arrived into four main periods:

- The Pre-ceramic Period (before pottery)

- The Formative Period (when farming and pottery began)

- The Period of Regional Development (when different regions grew unique cultures)

- The Period of Integration and the Arrival of the Incas

The Pre-ceramic period lasted until about 4200 BCE. The Las Vegas culture and The Inga Cultures were important then. The Las Vegas culture lived on the Santa Elena Peninsula on the coast of Ecuador between 9,000 and 6,000 BC. They were hunters, gatherers, and fishermen. Around 6,000 BC, people in this area were among the first to start farming. The Ingas lived in the mountains near present-day Quito between 9000 and 8000 BC, along an old trade route.

During the Formative Period, people moved from just hunting and gathering to more developed societies. They built permanent homes, farmed more, and started using pottery. New cultures appeared, like the Machalilla culture, Valdivia, and Chorrera on the coast; Cotocollao and The Chimba in the mountains; and Pastaza and Chiguaza in the eastern region.

The Valdivia culture is one of the earliest and most important. Their civilization dates back to 3500 B.C. They lived near the Valdivias and were the first people in the Americas to use pottery. They traveled the seas and traded with tribes in the Andes mountains and the Amazon rainforest. After the Valdivia, the Machalilla culture thrived along the coast between 2000 and 1000 BC. They were farmers and seem to be the first to grow corn in this part of South America. The Chorrera culture lived in the Andes and Coastal Regions between 1000 and 300 BC.

Regional Development: Cultures Grow Stronger

The Period of Regional Development is known for different regions developing their own unique ways of organizing society and politics. Some important cultures from this time were the Jambelí, Guangala, Bahia, Tejar-Daule, La Tolita, and Jama Coaque on the coast. In the mountains, there were Cerro Narrío Alausí, and in the Amazon jungle, the Tayos.

La Chimba, north of Quito, is where the oldest pottery in the northern Andes was found. Its people traded with villages on the coast and in the mountains. The Bahia culture lived from the Andes foothills to the Pacific Ocean. The Jama-Coaque culture lived in an area with wooded hills and wide beaches, allowing them to gather resources from both the jungle and the ocean.

The La Tolita culture developed in the coastal areas of southern Colombia and northern Ecuador between 600 BCE and 200 AD. Many archaeological sites show how artistic this culture was. Their artifacts include gold jewelry, beautiful masks, and figures that show a society with different social levels and complex ceremonies.

Integration and the Inca Arrival

During this period, tribes across Ecuador started to connect more. They built better homes to improve their lives and be less affected by the weather. In the mountains, the Cosangua-Píllaro, Capulí, and Piartal-Tuza cultures grew. In the eastern region, there was the Yasuní Phase, while the Milagro, Manteña, and Huancavilca cultures developed on the coast.

The Manteños: Masters of the Sea

The Manteños were the last major native culture on the coast, existing between 600 and 1534. They were the first to see Spanish ships sailing in the Pacific Ocean. They were excellent weavers and made textiles, gold, silver, and shell items. The Manteños were skilled sailors and created a large trade network that reached as far as Chile in the south and western Mexico in the north. Their main center was in the area of Manta, which was named after them.

The Huancavilcas: Brave Warriors

The Huancavilcas were the most important native culture in the Guayas region. They were known for being fierce warriors. The legend of Guayas and Quiles, which gave the city of Guayaquil its name, comes from the Huancavilca culture.

The Shyris and the Kingdom of Quito

The Kingdom of Quito was formed by the Quitus, Puruhaes, and Cañari people who lived in the Andean mountains of Ecuador. Their main settlement was in the area of modern-day Quito. The Quitus were not very strong militarily and had a small, not well-organized kingdom. Because of this, they couldn't put up much resistance and were easily defeated by the Shyris, another ancient native group who then joined the Kingdom of Quito. The Shyris ruled for over 700 years until the Inca Tupac Yupanqui invaded.

The Incas: A Short but Strong Rule

The Inca civilization began expanding northward from modern-day Peru in the late 1400s. They met strong resistance from several Ecuadorian tribes, especially the Cañari near Cuenca, and the Cara and Quitu people north of Quito.

The conquest of Ecuador began in 1463 under the ninth Inca ruler, Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. His son, Tupa, took command of the army and marched north through the mountains. By 1500, Tupa's son, Huayna Capac, had overcome the resistance of these groups and brought most of modern-day Ecuador into the Tawantinsuyu.

The Incas' influence lasted only about 50 years in Ecuador. Some parts of life, like traditional religious beliefs, stayed the same. But in other areas, like farming, land ownership, and how society was organized, Inca rule had a big impact, even though it was short.

Emperor Huayna Capac grew to love Quito and made it a second capital of the Inca Empire. He lived there in his later years and asked for his heart to be buried in Quito when he died around 1527. His sudden death, and the death of the next Inca heir from a strange disease (possibly smallpox), led to a fierce power struggle. His two sons, Huáscar and Atahualpa, fought for control. Atahualpa, who was his father's favorite and based in Quito, fought against Huáscar, who was based in Cuzco.

This civil war lasted for about five years, just before Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish arrived in 1532. The main battle of this civil war happened in Ecuador, near Riobamba. Atahualpa's troops defeated Huáscar's. Atahualpa's victory, just before the Spanish arrived, was largely due to the loyalty of two of Huayna Capac's best generals, who were with Atahualpa in Quito. This victory is still a source of pride for Ecuadorians.

Spanish Arrival and Conquest

As the Inca Civil War raged, the Spanish landed in Ecuador in 1530. Led by Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish explorers learned that the Inca Empire was weakened by conflict and disease. After getting more soldiers in September 1532, Pizarro went to meet the newly victorious Atahualpa.

When Pizarro arrived at Cajamarca, he sent a group, including Hernando de Soto, to meet Atahualpa. Atahualpa was amazed by these men in full armor, with long beards, riding horses (animals he had never seen). In town, Pizarro set a trap for the Inca leader, and the Battle of Cajamarca began. Even though the Inca forces were much larger, the Spanish had better weapons and tactics. Also, the Incas' most trusted generals were far away in Cuzco. This led to an easy defeat for the Incas and the capture of Emperor Atahualpa.

For the next year, Pizarro held Atahualpa for ransom. The Incas filled a room with gold and silver, hoping for his release. But on August 29, 1533, Atahualpa was executed. The Spanish then set out to conquer the rest of the Inca Empire, capturing Cuzco in November 1533.

Sebastián de Belalcázar, one of Pizarro's officers, had already left with soldiers to conquer Ecuador. Near Mount Chimborazo, he met and defeated the forces of the great Inca warrior Rumiñahui. Belalcázar was helped by Cañari tribesmen who guided them and fought alongside the Spanish. Rumiñahui retreated to Quito. While chasing the Inca army, Belalcázar met another large Spanish group led by Governor Pedro de Alvarado from Guatemala. Alvarado had sailed south without permission, landed on the Ecuadorian coast, and marched inland. Most of Alvarado's men joined Belalcázar for the attack on Quito. In 1533, Rumiñahui burned the city to prevent the Spanish from taking its treasures, destroying the ancient city.

In 1534, Sebastián de Belalcázar and Diego de Almagro founded the city of San Francisco de Quito on the ruins of the Inca capital, naming it in honor of Pizarro. It wasn't until December 1540 that Quito got its first captain-general, Gonzalo Pizarro, Francisco Pizarro's brother.

Belalcázar had also founded the city of Guayaquil in 1533, but local Huancavilca tribesmen had taken it back. Francisco de Orellana, another of Pizarro's officers, stopped the native rebellion and re-established Guayaquil in 1537. A century later, it became one of Spain's most important ports in South America.

Spanish Colonial Rule

Between 1544 and 1563, Ecuador was part of Spain's colonies in the Americas, under the Viceroyalty of Peru. It didn't have its own separate government. It stayed part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until 1720, when it joined the newly created Viceroyalty of New Granada. However, within this new viceroyalty, Ecuador was given its own special court and advisory body called an audiencia in 1563. This allowed it to talk directly with Spain on some matters. The Quito Audiencia was both a court and an advisory group to the viceroy.

The most common way the Spanish took over land was through the encomienda system. By the early 1600s, there were about 500 encomiendas in Ecuador. These were often large farms or estates. Even with many rules and reforms, the encomienda system became a form of forced labor, almost like slavery, for the native people. About half of Ecuador's native population lived on these encomiendas. The encomienda system lasted until almost the end of the colonial period.

The coastal lowlands north of Manta were not conquered by the Spanish, but by Africans from the Guinean coast. These people were slaves who were shipwrecked in 1570 while traveling from Panama to Peru. The Africans killed or enslaved the native men and married the women. Within a generation, they formed a mixed-race group called zambos who resisted Spanish rule for a long time and kept much of their own political and cultural freedom.

The coastal economy was based on shipping and trade. Guayaquil, even though it was destroyed by fires many times and suffered from diseases like yellow fever, was a busy trading center among the colonies. This trade was technically illegal under Spain's rules. Guayaquil also became the biggest shipbuilding center on the west coast of South America by the end of the colonial period.

Ecuador's economy, like Spain's, suffered a serious downturn for most of the 1700s. Textile production dropped a lot. Ecuador's cities slowly fell into disrepair, and by 1790, even the wealthy people became poor, selling their farms and jewelry to survive. However, the native population probably saw some improvement in their lives. When textile factories closed, many native people found less difficult work on farms or their traditional community lands. Ecuador's economic problems were made worse when the Jesuits were expelled in 1767 by King Charles III of Spain. Many missions in the eastern region were abandoned, and many of the best schools and farms lost the key people who made them successful.

Jesuits in Colonial Quito

Father Rafael Ferrer was the first Jesuit from Quito to explore and set up missions in the upper Amazon regions of South America from 1602 to 1610. This area belonged to the Royal Audience of Quito at that time. In 1602, Father Rafael Ferrer began exploring the Aguarico, Napo, and Marañon rivers (in what is now Ecuador and Peru). Between 1604 and 1605, he set up missions among the Cofan people. Father Rafael Ferrer was killed in 1610.

In 1637, two other Jesuits from Quito, Gaspar Cugia and Lucas de la Cueva, started missions in Mainas (or Maynas). These are now known as the Mainas missions.

In 1639, the Audiencia of Quito organized an expedition to explore the Amazon river again. The Quito Jesuit Father Cristobal de Acuña was part of this trip. The expedition started from the Napo river on February 16, 1639, and reached what is now Pará, Brazil, on the Amazon river, on December 12, 1639. In 1641, Father Cristobal de Acuña published a book in Madrid about his Amazon expedition. It was called Nuevo Descubrimiento del gran rio de las Amazonas (New Discovery of the Great River of the Amazons) and became an important book for studying the Amazon region.

Between 1637 and 1652, 14 missions were set up along the Marañon river and its southern branches. Jesuit Fathers de la Cueva and Raimundo de Santacruz opened two new ways to communicate with Quito, through the Pastaza and Napo rivers.

Between 1637 and 1715, Samuel Fritz founded 38 missions along the Amazon river, between the Napo and Negro rivers. These were called the Omagua Missions. Brazilian Bandeirantes (slave hunters) constantly attacked these missions starting in 1705. By 1768, only one Omagua mission was left, San Joaquin de Omaguas, which had been moved to a new location on the Napo river to escape the Bandeirantes.

In the huge territory of Mainas, the Jesuits of Quito met many native tribes who spoke 40 different languages. They founded a total of 173 Jesuit missions with 150,000 people. Because of constant diseases (like smallpox and measles) and wars with other tribes and the Bandeirantes, the number of Jesuit Missions was reduced to 40 by 1744. When the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish America in 1767, the Jesuits of Quito had 36 missions run by 25 Jesuits in the Audiencia of Quito, with a total of 20,000 people.

Fight for Independence and Birth of the Republic

The fight for independence in the Royal Audience of Quito was part of a larger movement across Spanish America. This movement was led by Criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas). The Criollos were unhappy with the special treatment given to Peninsulares (people born in Spain).

The spark for revolution came when Napoleon invaded Spain, removed King Ferdinand VII, and put his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne in 1808. Spanish citizens, upset by the French takeover, started forming local groups called juntas loyal to Ferdinand. A group of Quito's main citizens did the same. On August 10, 1809, they took power from the local Spanish officials, accusing them of planning to recognize Joseph Bonaparte. So, this early revolt against colonial rule was, strangely, an act of loyalty to the Spanish king.

It soon became clear that the Criollo rebels in Quito didn't have the popular support they expected. As loyal Spanish troops approached Quito, the rebels peacefully gave power back to the Spanish authorities. Even though they were promised no punishment, the Spanish authorities were harsh with the rebels. They jailed and mistreated many innocent citizens. This made the people of Quito angry. After several days of street fighting in August 1810, they won an agreement to be governed by a junta mostly made up of Criollos, but still led by the Spanish president of the Royal Audience of Quito.

Despite strong opposition from the Quito Audiencia, the Junta called for a meeting in December 1811 and declared the entire area of the audiencia independent from any government in Spain. Two months later, the Junta approved a constitution for the state of Quito. It set up democratic government but also recognized Ferdinand's authority if he returned to the Spanish throne. Soon after, the Junta decided to attack loyalist regions to the south in Peru. But their poorly trained and equipped troops were no match for the Viceroy of Peru's army, which finally crushed the Quito rebellion in December 1812.

Gran Colombia: A Big Dream

The second part of Ecuador's fight for freedom began in Guayaquil. Independence was declared there in October 1820 by a local group led by the poet José Joaquín de Olmedo. By this time, the independence movement was spread across the continent. There were two main armies: one led by the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar in the north, and another led by the Argentine José de San Martín in the south.

Unlike the unlucky Quito junta a decade earlier, the Guayaquil patriots could ask for help from other countries, like Argentina and Gran Colombia. Both soon sent soldiers to Ecuador. Antonio José de Sucre, Bolívar's brilliant young officer, arrived in Guayaquil in May 1821 and became the key figure in the military struggle against the Spanish forces.

After some early victories, Sucre's army was defeated at Ambato in the central mountains. He asked for help from San Martín, whose army was in Peru. With 1,400 fresh soldiers arriving from the south under Andrés de Santa Cruz Calahumana, the patriotic army's luck changed. A series of victories ended with the decisive Battle of Pichincha.

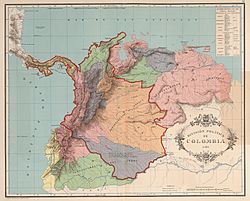

Two months later, Bolívar, who had liberated northern South America, entered Quito and was welcomed as a hero. Later that July, he met San Martín at the Guayaquil conference. Bolívar convinced San Martín, who wanted the port to return to Peruvian control, and the local wealthy Criollos that it was better for the former Quito Audiencia to join the liberated lands to the north. As a result, Ecuador became the District of the South within the Republic of Gran Colombia. This new country also included present-day Venezuela and Colombia, with Bogotá as its capital. This arrangement lasted for eight difficult years.

These were years when war dominated Ecuador. First, the country was on the front lines of Gran Colombia's efforts to free Peru from Spanish rule between 1822 and 1825. Then, in 1828 and 1829, Ecuador was in the middle of a war between Peru and Gran Colombia over their shared border. After a campaign that almost destroyed Guayaquil, Gran Colombia's forces, led by Sucre and Venezuelan General Juan José Flores, won. The Treaty of 1829 set the border along the line that had separated the Quito audiencia and the Viceroyalty of Peru before independence.

During these years, Ecuador's population was divided into three groups: those who liked things as they were, those who wanted to join Peru, and those who wanted the former audiencia to be fully independent. The last group won after Venezuela left Gran Colombia in 1830. In May of that year, a group of important people in Quito met to end the union with Gran Colombia. In August, a special assembly wrote a constitution for the State of Ecuador, named for its location on the equator. General Flores was put in charge of political and military affairs. He remained the most powerful political figure during Ecuador's first 15 years of independence.

Early Years of the Republic

Before 1830 ended, both Marshal Sucre and Simón Bolívar died. Sucre was murdered (some historians say by order of a jealous General Flores), and Bolívar died from tuberculosis.

Juan José Flores, known as the founder of the republic, was a foreign military leader. Born in Venezuela, he fought in the independence wars with Bolívar, who made him governor of Ecuador when it was part of Gran Colombia. As a leader, he seemed mostly interested in keeping his power. Military spending, from the independence wars and a failed campaign to take Cauca Province from Colombia in 1832, kept the government's money empty. In that same year, Ecuador took control of the Galapagos Islands.

People became unhappy across the country by 1845. An uprising in Guayaquil forced Flores to leave the country. Because their movement won in March (marzo), the anti-Flores group became known as marcistas. They were a very mixed group, including liberal thinkers, conservative religious leaders, and successful business people from Guayaquil.

The next fifteen years were very chaotic for Ecuador. The marcistas fought among themselves almost constantly and also had to fight against Flores's repeated attempts from exile to overthrow the government. The most important person of this time was General José María Urbina. He first came to power in 1851 through a sudden takeover, stayed as president until 1856, and then continued to control politics until 1860. During this time, Urbina and his main rival, García Moreno, created the big political divide between Liberals from Guayaquil and Conservatives from Quito. This division remained the main political struggle in Ecuador until the 1980s.

By 1859, known by Ecuadorian historians as "the Terrible Year," the nation was almost in chaos. Local strongmen had declared several regions independent from the central government. One of these leaders, Guillermo Franco from Guayaquil, signed the Treaty of Mapasingue. This treaty gave the southern provinces of Ecuador to an invading Peruvian army led by General Ramón Castilla. This action was so outrageous that it united some previously opposing groups. García Moreno, putting aside his plan to place Ecuador under French protection and his differences with General Flores, worked with the former dictator to stop the local rebellions and force out the Peruvians. This effort ended with the defeat of Franco's Peruvian-backed forces at the Battle of Guayaquil, which led to the cancellation of the Treaty of Mapasingue. This marked the end of Flores's long career and the beginning of García Moreno's rise to power.

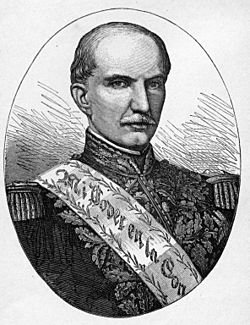

The Conservative Era (1860–1895)

Gabriel García Moreno was a leading figure of Ecuadorian conservatism. He was attacked with a machete and died shortly after starting his third presidential term in 1875.

Between 1852 and 1890, Ecuador's exports grew a lot. Cacao, the most important export product in the late 1800s, grew significantly. The agricultural businesses that exported goods, mainly located in the coastal region near Guayaquil, became closely linked with the Liberals. The Liberals' political power also grew steadily during this time. After García Moreno's death, it took the Liberals twenty years to become strong enough to take control of the government in Quito.

The Liberal Era (1895–1925)

The new era brought in liberalism. Eloy Alfaro, who led the government to help people in the rural areas of the coast, is famous for finishing the railroad connecting Guayaquil and Quito. He also separated the church and state, started many public schools, brought in civil rights like freedom of speech, and made civil marriages and divorce legal.

Alfaro also faced opposition within his own party, led by General Leonidas Plaza. Alfaro's death was followed by a period of economic liberalism (1912–25), when banks gained almost complete control of the country. In the 1920s, Ecuador's main export, cacao beans, were destroyed by disease. At the same time, cacao producers faced more competition from West Africa. The loss of export money seriously hurt the economy.

Public unhappiness, along with the ongoing economic crisis and a sick president, led to a peaceful overthrow of the government in July 1925. Unlike previous times when the military got involved in politics, the 1925 takeover was done by a group of young officers, not just one strong leader. These officers came to power with a plan for many social reforms. These included dealing with the failing economy, setting up the Central Bank as the only bank allowed to print money, and creating a new system for the government's budget and customs.

Early 20th Century Challenges

Much of the 20th century was shaped by José María Velasco Ibarra, who was president five times. His first term began in 1934, and his last ended in 1972. However, he only completed one full term, from 1952 to 1956.

The century was also marked by a long-standing border dispute between Peru and Ecuador. In 1941, Ecuador invaded Peruvian territory, but the Peruvians fought back and forced them to retreat. At that time, Ecuador was dealing with internal political problems and was not ready for a war.

With World War II happening, Ecuador tried to solve the border issue with help from other countries. In Brazil, four "Guarantor" states (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and the United States) oversaw negotiations between the two countries. The resulting agreement is known as the Rio Protocol. This agreement caused a surge of national pride and strong opposition in Ecuador, leading to an uprising and the overthrow of the government.

The Postwar Era (1944–1948)

On May 31, 1944, many people in Quito stood in the rain to hear Velasco promise a "national rebirth." He spoke of social justice and punishing the "corrupt Liberal wealthy class" responsible for "staining the national honor." People believed they were seeing the start of a popular revolution. Liberal supporters were quickly jailed or sent away, while Velasco criticized the business community and the political right. However, the leftist groups within Velasco's Democratic Alliance, who controlled the assembly writing a new constitution, were disappointed.

In May 1945, after a year of growing tension between the president and the assembly, Velasco condemned and rejected the newly finished constitution. After dismissing the assembly, Velasco held elections for a new one. In 1946, this new assembly wrote a much more conservative constitution that Velasco approved. For a short time, Conservatives replaced the left as Velasco's main supporters.

Instead of fixing the country's economic problems, Velasco made them worse by funding his friends' questionable plans. Inflation continued to rise, hurting people's living standards. By 1947, foreign money reserves were dangerously low. In August, when Velasco was removed by his defense minister, no one stood up to defend the man who, just three years earlier, had been seen as the nation's savior. Over the next year, three different men briefly held power. Then, Galo Plaza Lasso, running with a group of independent Liberals and socialists, narrowly won the presidential elections. His inauguration in September 1948 began what would be the longest period of stable constitutional rule since the Liberal era of 1912–24.

Stable Rule (1947–1960)

Galo Plaza was different from earlier Ecuadorian presidents because he focused on development and using experts in government. His most important contribution was his dedication to democratic principles. As president, he promoted Ecuador's agricultural exports, especially bananas, which brought economic stability. During his time in office, an earthquake near Ambato badly damaged the city and surrounding areas, killing about 8,000 people. He could not run for re-election, and he left office in 1952 as the first president in 28 years to complete his full term.

The economic boost from the banana boom of the 1950s helped stabilize politics. Even Velasco, who was elected president for the third time in 1952, managed to serve a full four-year term. However, Velasco's fourth term started a new period of crisis, instability, and military control, ending the idea that the political system had become more democratic.

Modern Ecuador Develops

Instability and Military Governments (1960–1979)

In 1963, the army overthrew President Carlos Julio Arosemena Monroy, falsely accusing him of "sympathizing with communism." Some sources suggest the United States encouraged this takeover to remove a government that wouldn't break ties with Cuba.

In 1976, the military leaders, pressured by public opinion, began a process to return to constitutional rule. This was seen as a good time for the ruling classes to make their power seem more legitimate by bringing back traditional ways of controlling government. However, disagreements among the Armed Forces leaders led to different ideas for a new constitution. Through a public vote, a new Constitution was approved in January 1978. It gave more representation to groups traditionally left out of power, such as native people, labor unions, and leftist political parties. In the 1978-79 elections, the progressive candidate, Jaime Roldós Aguilera, won against the conservative Sixto Durán Ballén, who had the military's quiet support.

Return to Democracy (1979–1990)

Jaime Roldós Aguilera, democratically elected in 1979, became president of a nation that had changed a lot during 17 years of military rule. There were impressive signs of economic growth between 1972 and 1979. The government's budget grew by about 540 percent, and exports and income per person increased by 500 percent. Industrial development also improved, helped by new oil wealth and Ecuador's special treatment under the Andean Common Market.

Roldós was killed, along with his wife and the minister of defense, in an airplane crash in the southern province of Loja on May 24, 1981. His death led to much public discussion. Some Ecuadorians blamed the Peruvian government because the crash happened near the border where the two nations had fought in the Paquisha War. Many leftists, pointing to a similar crash that killed Panamanian President Omar Torrijos Herrera less than three months later, blamed the United States government.

Roldós's replacement, Osvaldo Hurtado, immediately faced an economic crisis caused by the sudden end of the oil boom. Huge foreign loans, started during the second military government and continued under Roldós, led to a foreign debt of almost US$7 billion by 1983. The country's oil reserves dropped sharply in the early 1980s because of failed exploration and quickly increasing domestic use. The economic crisis got worse in 1982 and 1983 due to extreme weather changes, including severe drought and flooding, caused by "El Niño." Experts estimated damage to the country's infrastructure at US$640 million, with trade losses of about US$300 million. Economic growth fell, and the inflation rate in 1983, at 52.5%, was the highest ever recorded.

Outside observers noted that, despite being unpopular, Hurtado deserved credit for keeping Ecuador in good standing with international financial groups and for strengthening Ecuador's democratic political system under very difficult conditions. When León Febres Cordero took office on August 10, there was no end in sight to the economic crisis or the intense political struggles.

During his first years, Febres Cordero introduced free-market economic policies, took a strong stand against terrorism, and sought close ties with the United States. His time in office was marked by bitter arguments with other parts of the government and his own brief kidnapping by some military members. A devastating earthquake in March 1987 stopped oil exports and worsened the country's economic problems.

Rodrigo Borja Cevallos of the Democratic Left party won the presidency in 1988. His government worked to improve human rights and made some reforms, especially opening Ecuador to foreign trade. However, ongoing economic problems hurt the popularity of his party, and opposition parties gained control of Congress in 1990.

Economic Crisis (1990–2000)

In 1992, Sixto Durán Ballén won his third attempt at the presidency. His strict economic measures were unpopular, but he managed to push a few modernization plans through Congress. Durán Ballén's vice president, Alberto Dahik, was the main person behind the government's economic policies. But in 1995, Dahik fled the country to avoid being charged with political corruption after a heated political fight with the opposition.

A war with Peru, called the Cenepa War, broke out in January–February 1995 in a small, remote area where the border set by the 1942 Rio Protocol was disputed. The Durán Ballén government can be credited with starting the talks that would finally settle the border dispute.

In 1996, Abdalá Bucaram, from the populist Ecuadorian Roldosista Party, won the presidency. He promised popular economic and social reforms. Almost from the start, Bucaram's government faced many accusations of corruption. Because the president was unpopular with labor unions, businesses, and professional groups, Congress removed Bucaram in February 1997, saying he was mentally unfit. Congress replaced Bucaram with Interim President Fabián Alarcón.

In May 1997, after the protests that led to Bucaram's removal and Alarcón's appointment, the people of Ecuador called for a National Assembly to change the Constitution and the country's political structure. After a little over a year, the National Assembly created a new Constitution.

Elections for Congress and the first round of presidential elections were held on May 31, 1998. No presidential candidate won a majority, so a second election between the top two candidates – Quito Mayor Jamil Mahuad and Social Christian Álvaro Noboa Pontón – was held on July 12, 1998. Mahuad won by a small margin. He took office on August 10, 1998. On the same day, Ecuador's new constitution became law.

Mahuad faced a difficult economic situation, especially due to the Asian financial crisis. The currency lost 15% of its value, fuel and electricity prices increased five times, and public transport prices went up by 40%. The government was preparing to sell off several key parts of the economy: oil, electricity, telecommunications, ports, airports, railways, and the post office. The stopping of a first general strike caused three deaths. The social situation was very bad: more than half the population was unemployed, 60% lived below the extreme poverty line, and public employees had not been paid for three months. Another increase in sales tax, combined with ending government help for domestic gas, electricity, and diesel, caused new protests. In Latacunga, the army shot native people who blocked the Pan-American Highway, injuring 17 people with bullets.

The final blow to Mahuad's government was his decision to stop using the local currency, the sucre, and replace it with the US dollar (a policy called dollarization). This caused huge unrest. Poor people struggled to exchange their now useless sucres for US dollars and lost their savings, while wealthy people (who already had their money in US dollars) gained wealth. During Mahuad's term, which was hit by a recession, the economy shrank a lot, and inflation reached up to 60 percent.

Also, corruption scandals were a big public concern. Former Vice President Alberto Dahik, who designed the economic plan, fled abroad after being accused of "questionable use of special funds." Former President Fabián Alarcón was arrested for allegedly paying salaries for over a thousand fake jobs. President Mahuad did achieve a well-received peace agreement with Peru on October 26, 1998.

Instability (2000–2007)

On January 21, 2000, during protests in Quito by native groups, the military and police refused to control public order. This led to what became known as the 2000 Ecuadorean coup d'état. Protesters entered the National Assembly building and declared a three-person military government, similar to past takeovers in Ecuador. Military officers supported this idea. During a confusing night of failed talks, President Mahuad was forced to flee the presidential palace for his safety. Vice President Gustavo Noboa took charge. Mahuad went on national television the next morning to support Noboa as his successor. The military leaders who were effectively running the country also supported Noboa. The Ecuadorian Congress then met in an emergency session in Guayaquil on January 22 and officially confirmed Noboa as President.

The US dollar became the only official currency of Ecuador in 2000. Although Ecuador's economy started to improve in the following months, Noboa's government faced strong criticism for continuing the dollarization policy, ignoring social problems, and other important issues.

Retired Colonel Lucio Gutiérrez, a member of the military group that overthrew Mahuad, was elected president in 2002 and took office on January 15, 2003. Gutiérrez's Patriotic Society Party had only a few seats in Congress, so he needed support from other parties to pass laws.

In December 2004, Gutiérrez illegally dissolved the Supreme Court and appointed new judges. This move was generally seen as a favor to former President Abdalá Bucaram, whose political party had supported Gutiérrez and helped stop attempts to remove him in late 2004. The new Supreme Court dropped corruption charges against Bucaram, who was in exile and soon returned to the politically unstable country. The political corruption in these actions finally led the middle classes of Quito to demand Gutiérrez's removal in early 2005. In April 2005, the Ecuadorian Armed Forces announced they were no longer supporting the President. After weeks of public protests, Gutiérrez was overthrown in April. Vice President Alfredo Palacio became president and promised to finish the term and hold elections in 2006.

Rafael Correa's Time (2007-2017)

On January 15, 2007, the social democrat Rafael Correa became President of Ecuador, promising to call a special assembly to write a new constitution and focus on reducing poverty. The 2007-8 Ecuadorian Constituent Assembly wrote the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador, which was approved by a public vote in the Ecuadorian constitutional referendum, 2008. This new socialist constitution brought in left-leaning reforms.

In November 2009, Ecuador faced an energy crisis that led to power cuts across the country.

Between 2006 and 2016, poverty in Ecuador decreased from 36.7% to 22.5%. The average income per person grew by 1.5 percent each year (compared to 0.6 percent in the two decades before). At the same time, the gap between rich and poor, measured by the Gini index, decreased.

Starting in 2007, President Rafael Correa began "The Citizens' Revolution," a movement with left-wing policies. Some people called it populist. Correa was able to use the 2000s commodities boom (when prices for raw materials were high) to fund his policies, using China's need for raw materials. Through China, Correa got loans that had few strict rules, unlike other lenders. With this money, Ecuador invested in social welfare programs, reduced poverty, and increased the average standard of living. At the same time, Ecuador's economy grew. These policies made Correa popular, and he was re-elected three times between 2007 and 2013.

As the Ecuadorian economy started to slow down in 2014, Correa decided not to run for a fourth term. By 2015, protests happened against Correa after he introduced austerity measures (cuts in government spending) and increased inheritance taxes. Instead, Lenín Moreno, who was a strong supporter of Correa and had been his vice-president for over six years, was expected to continue Correa's policies and "21st century socialism." He ran on a generally left-wing platform similar to Correa's.

A Shift in Direction (2017–Present)

Moreno's Presidency (2017–2021)

After Rafael Correa's three terms (2007-2017), his former Vice President Lenín Moreno became president for four years (2017–21). In the weeks after his election, Moreno started to move away from Correa's policies. He shifted the left-wing PAIS Alliance party away from left-wing politics and towards neoliberal governance (more free-market policies). Despite these changes, Moreno still called himself a social democrat. Moreno then led the 2018 Ecuadorian referendum, which brought back presidential term limits that Correa had removed. This stopped Correa from running for a fourth term in the future. When he was elected, Moreno had a very high approval rating of 79 percent. However, Moreno's changes and his campaign promises, which differed from his predecessor's, upset both former President Correa and many of his own party's supporters. In July 2018, an arrest warrant was issued for Correa due to alleged corruption during his time in office.

Because Correa's government had borrowed a lot of money to fund social programs, and due to the 2010s oil glut (when oil prices dropped), public debt tripled in five years. Ecuador eventually had to use money from the Central Bank of Ecuador's reserves. In total, Ecuador was left with $64 billion in debt and was losing $10 billion annually. On August 21, 2018, Moreno announced economic austerity measures to reduce government spending and the budget deficit. Moreno said these measures aimed to save $1 billion. They included reducing fuel subsidies (government help to keep fuel prices low), removing subsidies for gasoline and diesel, and closing or combining several government agencies. Groups representing native people and labor unions criticized these moves.

At the same time, Lenín Moreno changed Ecuador's foreign policy, moving away from his predecessor's left-leaning approach. In August 2018, Ecuador left the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (Alba), a group of left-wing governments led by Venezuela. In October 2018, Moreno's government cut diplomatic ties with the Nicolás Maduro government of Venezuela, a close ally of Rafael Correa. In March 2019, Ecuador left the Union of South American Nations. Ecuador was a founding member of this group, started by left-wing governments in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2008. Ecuador also asked UNASUR to return its headquarters building in Quito. In June 2019, Ecuador agreed to allow US military planes to use an airport on the Galapagos Islands.

In October 2019, Lenín Moreno announced a package of economic measures as part of a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to get $4.2 billion in credit. These measures, known as "el paquetazo," included ending fuel subsidies, removing some import taxes, and cutting benefits and wages for public workers. This caused huge protests starting on October 3, 2019. On October 8, President Moreno moved his government to the coastal city of Guayaquil after anti-government protesters took over parts of Quito, including the Carondelet Palace. On the same day, Moreno accused his predecessor Rafael Correa of organizing a coup against the government with help from Venezuela's Nicolás Maduro, a charge Correa denied. Later that day, authorities stopped oil production at the Sacha oil field, which produces 10% of the nation's oil, after protesters occupied it. Two more oil fields were taken by protesters soon after. Demonstrators also captured broadcast antennas, forcing state TV and radio offline in some parts of the country. Native protesters, organized by the CONAIE, blocked most of Ecuador's main roads, completely cutting off transport routes to the city of Cuenca. On October 9, protesters briefly entered and occupied the National Assembly building before police used tear gas to drive them out. Violent clashes broke out between demonstrators and police as the protests spread. Late on October 13, the Ecuadorian government and CONAIE reached an agreement during a televised negotiation. Both sides agreed to work together on new economic measures to fight overspending and debt. The government agreed to end the austerity measures that caused the protests, and the protesters agreed to end the two-week-long demonstrations. President Moreno agreed to withdraw Decree 883, the IMF-backed plan that significantly raised fuel costs.

Relations with the United States improved a lot during Lenin Moreno's presidency. In February 2020, his visit to Washington was the first meeting between an Ecuadorian and US president in 17 years.

Lasso's Presidency (Since 2021)

The April 2021 election ended with a win for conservative former banker, Guillermo Lasso. He received 52.4% of the vote, compared to 47.6% for left-wing economist Andrés Arauz, who was supported by former president Rafael Correa. Lasso had previously finished second in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections. On May 24, 2021, Guillermo Lasso was sworn in as the new President of Ecuador, becoming the country's first right-wing leader in 14 years.

In October 2021, President Lasso declared a 60-day state of emergency to fight crime. In October 2022, a violent riot among prisoners in a central Ecuador prison caused 16 deaths. There have been many clashes between rival groups of prisoners in Ecuador's state prisons.

A series of protests against the economic policies of Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso, caused by rising fuel and food prices, took place in June 2022. Started mainly by native activists, especially CONAIE, the protests were later joined by students and workers also affected by the price increases. Lasso condemned the protests and called them an attempted "coup d'état" against his government.

As a result of the protests, Lasso declared a state of emergency. When the protests blocked roads and ports in Quito and Guayaquil, there were food and fuel shortages across the country. Lasso was criticized for allowing violent and deadly responses towards protesters. The President narrowly avoided being removed from office in a vote in Congress. At the end of June, protesters agreed to stop their demonstrations and blockades in return for a government agreement to discuss and try to meet their demands.

Lasso proposed several constitutional changes to help his government respond to rising crime. In a referendum in February 2023, voters largely rejected his proposed changes. This result weakened Lasso's political position. Meanwhile, Lasso's government faced accusations of corruption. Citing those accusations and claiming that the government had failed to meet its demands from June 2022, CONAIE called on Lasso to resign and declared itself in a state of "permanent mobilization," threatening more protests.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Ecuador para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Ecuador para niños

- 1830 Constitution of Ecuador

- 2008 Constitution of Ecuador

- Economic history of Ecuador

- History of Latin America

- History of South America

- History of the Americas

- Military history of Ecuador

- Politics of Ecuador

- President of Ecuador

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |