Inca Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Realm of the Four Parts

Tawantinsuyu (Quechua)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1438–1533/1572 | |||||||||||||||||||

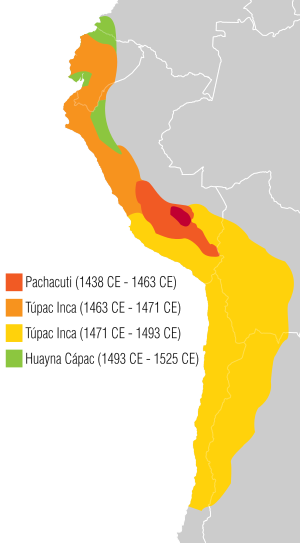

The Inca Empire at its greatest extent c. 1525

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Cusco | ||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Quechua | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Aymara, Puquina, Jaqi family, Muchik and scores of smaller languages. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Inca religion | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Divine, absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sapa Inca | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1438–1471

|

Pachacuti | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1471–1493

|

Túpac Inca Yupanqui | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1493–1527

|

Huayna Capac | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian era | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Pachacuti created the Tawantinsuyu

|

1438 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1529–1532 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• Spanish conquest led by Francisco Pizarro

|

1533/1572 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• End of the last Inca resistance

|

1572 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1527 | 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The Inca Empire was the biggest empire in the Americas before Christopher Columbus arrived. Its main city was Cusco. The Inca people started their civilization in the mountains of Peru around the early 1200s. The Spanish began to conquer the Inca Empire in 1532. By 1572, the last Inca state was fully taken over.

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas took over a large part of western South America. At its largest, the empire included modern-day Peru, western Ecuador, parts of Bolivia, northwest Argentina, the tip of Colombia, and a large part of Chile. It was as big as some historical empires in Europe and Asia. Their official language was Quechua.

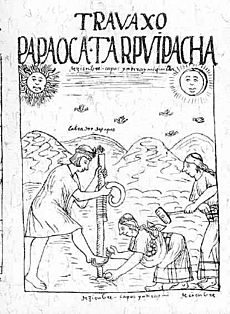

The Inca Empire was special because it didn't have many things found in other big civilizations. For example, they didn't use wheels, draft animals, iron, or steel. They also didn't have a writing system. Even so, they built "one of the greatest imperial states in human history." The Inca Empire was known for its huge buildings, especially those made of stone. They also had a large road network that reached everywhere in the empire. They made beautiful textiles and used knotted strings called quipu to keep records. They also had smart ways to farm in tough environments.

The Inca Empire worked mostly without money or markets. Instead, people traded goods and services based on helping each other. "Taxes" meant that people had to work for the Empire. In return, the Inca rulers gave people land and goods. They also provided food and drinks at big parties for their people.

Many local ways of worship continued in the empire. Most of these involved local sacred places called Huacas. However, the Inca leaders encouraged worship of Inti, their sun god. They believed their king, the Sapa Inca, was the "son of the sun."

Contents

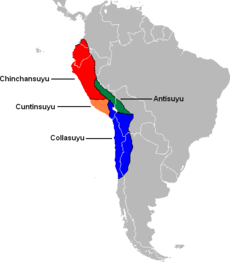

What Does "Inca" Mean?

The Inca people called their empire Tawantinsuyu. This means "the four suyu" or "four regions." In Quechua, tawa means four, and -ntin means a group. So, Tawantinsuyu was a group of four regions that met at the capital city, Cusco. These four regions were: Chinchaysuyu (north), Antisuyu (east, the Amazon jungle), Qullasuyu (south), and Kuntisuyu (west). The name Tawantinsuyu showed that it was a union of these provinces.

The word Inka today means "ruler" or "lord" in Quechua. This term didn't just mean the "King" or Sapa Inka. It also referred to the Inca nobles. These nobles were a small part of the empire's population, maybe 15,000 to 40,000 people. But they ruled over about 10 million people!

When the Spanish arrived, they called the land "Peru," even though the natives knew it as Tawantinsuyu. The name "Inca Empire" came from writings in the 16th century.

History of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire was the last part of thousands of years of Andean civilizations. The Andean civilization is one of the few in the world that developed on its own, not from other cultures.

Before the Inca Empire, there were two other large empires in the Andes. These were the Tiwanaku (around 300–1100 AD) near Lake Titicaca and the Wari (around 600–1100 AD) near Ayacucho. The Wari controlled the Cusco area for about 400 years. Many things the Inca Empire did came from these earlier cultures. These include thousands of miles of roads, large administrative centers with stone buildings, terraced mountainsides, and making huge amounts of goods.

How the Inca Empire Began

The Inca people started as a tribe that raised animals in the Cusco area around the 12th century. Their stories say they came from three caves. The main cave was called Qhapaq T'uqu. From this cave came four brothers and four sisters. They were: Ayar Manco, Ayar Cachi, Ayar Awqa, and Ayar Uchu. The sisters were Mama Ocllo, Mama Raua, Mama Huaco, and Mama Qura. Other people who became ancestors of Inca clans came from the other caves.

Ayar Manco carried a special golden staff. Where this staff landed, the people would settle down. They traveled for a long time. Ayar Cachi bragged about his strength. His siblings tricked him into going back to the cave for a sacred llama. They then trapped him inside.

Ayar Uchu decided to stay on top of the cave to watch over the Inca people. As soon as he said this, he turned to stone. They built a shrine around the stone, and it became a sacred object. Ayar Auca got tired and left to travel alone. Only Ayar Manco and his four sisters remained.

Finally, they reached Cusco. The staff sank into the ground. Before they arrived, Mama Ocllo had already had a child with Ayar Manco, named Sinchi Roca. The people already living in Cusco fought to keep their land. But Mama Huaca was a strong fighter. When enemies attacked, she threw her bolas (stones tied together) at a soldier and killed him. The other people got scared and ran away.

After this, Ayar Manco became known as Manco Cápac, the founder of the Inca. It is said he and his sisters built the first Inca homes in the valley. When his time came, Manco Cápac also turned to stone. His son, Sinchi Roca, became the second Inca emperor.

Growth of the Kingdom of Cusco

Under Manco Cápac, the Inca formed a small city-state called the Kingdom of Cusco. In 1438, they began to expand greatly under their leader, Sapa Inca Pachacuti-Cusi Yupanqui. His name meant "earth-shaker." He got this name after conquering the Tribe of Chancas. During his rule, he and his son, Tupac Yupanqui, brought much of modern-day Peru under Inca control.

How the Empire Was Organized

Pachacuti changed the Kingdom of Cusco into the Tahuantinsuyu. This had a main government led by the Inca ruler. It also had four regional governments with strong leaders: Chinchasuyu (northwest), Antisuyu (northeast), Kuntisuyu (southwest), and Qullasuyu (southeast). Pachacuti is also thought to have built Machu Picchu. It might have been a family home, a summer retreat, or a farming station.

Pachacuti sent spies to areas he wanted to add to his empire. They brought back information about how these places were run, their military strength, and their wealth. Then, he sent messages to their leaders, telling them how good it would be to join his empire. He offered them gifts like fine textiles and promised they would become richer.

Most leaders accepted Inca rule peacefully. If they refused, the Inca army would conquer them. After a conquest, the local rulers were usually executed. Their children were taken to Cusco to learn about Inca ways of ruling. Then, they would return to govern their homelands. This helped the Inca bring them into the Inca nobility. Sometimes, Inca daughters would marry into these families, connecting different parts of the empire.

Expansion and Strength

Traditionally, the Inca ruler's son led the army. Pachacuti's son, Túpac Inca Yupanqui, started conquests in the north in 1463. He continued these as Inca ruler after Pachacuti died in 1471. Túpac Inca's most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor. This was the Inca's only serious rival on the Peruvian coast. Túpac Inca's empire then stretched north into what is now Ecuador and Colombia.

Túpac Inca's son, Huayna Cápac, added a small part of land to the north in Ecuador. At its largest, the Inca Empire included modern-day Peru, parts of western and south-central Bolivia, southwest Ecuador, and Colombia. It also included a large part of modern-day Chile, up to the Maule River.

The empire's push into the Amazon Basin near the Chinchipe River was stopped by the Shuar in 1527. The empire also reached parts of northern Argentina and southern Colombia. However, most of the southern Inca empire, called Qullasuyu, was in the Altiplano (high plains).

The Inca Empire was a mix of many languages, cultures, and peoples. Not all parts of the empire were equally loyal. Also, local cultures were not always fully integrated. The Inca empire's economy was based on trading luxury goods and labor as a form of tax.

Inca Civil War and Spanish Conquest

Spanish explorers called conquistadors, led by Francisco Pizarro, traveled south from what is now Panama. They reached Inca land by 1526. They saw that it was a rich land with much treasure. After another trip in 1529, Pizarro went to Spain. He got permission from the king to conquer the region and rule it.

When the conquistadors returned to Peru in 1532, the empire was weak. There was a war between the sons of Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa. Also, newly conquered areas were restless. Even more importantly, diseases like smallpox, influenza, typhus, and measles had spread from Central America. The first wave of European diseases in the Inca Empire was probably in the 1520s. It killed Huayna Capac, his chosen heir, and many other Inca people.

Pizarro's forces had 168 men, one cannon, and 27 horses. The conquistadors used lances, arquebuses (early guns), steel armor, and long swords. The Inca, however, used weapons made of wood, stone, copper, and bronze. Their armor was made from Alpaca fiber. This put them at a big disadvantage. None of their weapons could get through the Spanish steel armor. Also, since there were no horses in Peru, the Inca didn't know how to fight against cavalry (soldiers on horseback).

The first fight between the Inca and Spanish was the Battle of Puná, near modern-day Guayaquil, Ecuador. Pizarro then started the city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore. He returned with an invitation to meet the Inca leader, Atahualpa. Atahualpa had won the civil war against his brother. He was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops. At that moment, they were only armed with hunting tools like knives and lassos for llamas.

Pizarro and some of his men met Atahualpa, who had only a small group with him. The Inca offered them ceremonial chicha (a drink) in a golden cup, but the Spanish refused it. The Spanish interpreter, Friar Vincente, read a message called the "Requerimiento." It demanded that Atahualpa and his empire accept the rule of King Charles I of Spain and become Christians. Atahualpa rejected the message and told them to leave. After this, the Spanish attacked the mostly unarmed Inca. They captured Atahualpa and held him hostage, forcing the Inca to cooperate.

Atahualpa offered the Spanish enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in and twice that amount of silver. The Inca paid this ransom. But Pizarro tricked them and refused to release Atahualpa. While Atahualpa was imprisoned, Huáscar was killed elsewhere. The Spanish said this was Atahualpa's order. This was one of the reasons they used to execute Atahualpa in August 1533.

Many different groups ruled by the Inca welcomed the Spanish. They saw the Spanish as liberators and were happy to share rule over the Andean farmers and miners. Many local leaders, called Kurakas, continued to serve the Spanish rulers, just as they had served the Inca. Besides trying to spread Christianity, the Spanish didn't change much about the Inca society and culture until Francisco de Toledo became ruler from 1569 to 1581.

End of the Inca Empire

The Spanish put Atahualpa's brother, Manco Inca Yupanqui, in charge. For a while, Manco worked with the Spanish as they fought to stop resistance in the north. Meanwhile, a friend of Pizarro, Diego de Almagro, tried to claim Cusco. Manco tried to use this fight between the Spanish to his advantage. He recaptured Cusco in 1536, but the Spanish took the city back. Manco Inca then went to the mountains of Vilcabamba and created a small Neo-Inca State. He and his successors ruled there for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or causing revolts. In 1572, the last Inca stronghold was conquered. The last ruler, Túpac Amaru, Manco's son, was captured and executed. This ended the Inca state's fight against the Spanish.

After the Inca Empire fell, many parts of Inca culture were destroyed, including their farming system. Spanish officials used the Inca mita labor system for their own goals, sometimes very cruelly. One person from each family was forced to work in gold and silver mines, like the huge silver mine at Potosí. If a family member died, which often happened within a year or two, the family had to send a replacement.

Diseases like smallpox spread quickly even before the Spanish invaders fully arrived. The efficient Inca road system probably helped these diseases spread. Smallpox was just the first epidemic. Other diseases, including a probable typhus outbreak in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618, all badly affected the Inca people.

Inca Society

Population of the Empire

The exact number of people living in Tawantinsuyu at its peak is not known. Estimates range from 4 to 37 million. Most guesses are between 6 and 14 million people. The Inca kept excellent records using their quipus (knotted strings). However, how to read them was lost. Almost all quipus either fell apart over time or were destroyed by the Spanish.

Languages Spoken

The empire had many different languages. Some of the most important were Quechua, Aymara, Puquina, and Mochica. To manage this diversity, the Inca leaders encouraged the use of Quechua. They made it the official language or common language. Most communities learned to speak some Quechua to talk with the Inca leaders, but they usually kept their native languages too. The Incas also had their own special language, called Qhapaq simi ("royal language").

The Incas did not have a written language in the way we think of it. However, they recorded stories through paintings on vases and cups called qirus. These paintings often had geometric patterns called toqapu. Researchers think these patterns might have been a form of written communication, but it's not clear. The Incas also kept records using quipus.

Stages of Life and Gender

All babies were called 'wawa' when they were born. When a child turned three, they had a "coming of age" ceremony called the rutuchikuy. This ceremony meant the child was entering a stage of "ignorance." During this event, the family invited relatives for food and dancing. Each family member would receive a lock of the child's hair. After this, the father would shave the child's head. This stage was about being young and learning, which the child would grow out of.

The next important celebration was for a child becoming mature. This was called warachikuy for boys and qikuchikuy for girls. The warachikuy ceremony included dancing, fasting, tasks to show strength, and family events. The boy would get new clothes and learn how to act as an unmarried man. The qikuchikuy meant a girl had reached puberty. She was given a new name, adult clothes, and advice.

Between ages 20 and 30, people were considered young adults. They were ready for serious thinking and work. Young adults could stay young by living at home and helping their community. People became fully mature and independent only after they got married.

| Table 7.1 from R. Alan Covey's Article | |||

| Age | Social Value of Life Stage | Female Term | Male Term |

| < 3 | Conception | Wawa | Wawa |

| 3–7 | Ignorance (not speaking) | Warma | Warma |

| 7–14 | Development | Thaski (or P'asña) | Maqt'a |

| 14–20 | Folly | Sipas (unmarried) | Wayna (unmarried) |

| 20+ | Maturity (body and mind) | Warmi | Qhari |

| 70 | Infirmity | Paya | Machu |

| 90 | Decrepitude | Ruku | Ruku |

Marriage in Inca Society

In the Inca Empire, men usually married at age 20, and women at age 16. Men with high status could have many wives, but others could only have one. Marriages usually happened within the same social class. Once married, women were expected to cook, gather food, and care for children and animals. Girls and mothers also kept the house tidy for public inspectors. These duties continued even when wives were pregnant.

If a couple felt the marriage wasn't working, or if the woman wanted to go back to her parents' home, they could divorce. Divorce was only allowed if the couple did not have children together.

Roles of Genders

Some historians believe that male and female roles were seen as equal in Inca society. Women's daily tasks included spinning, watching children, weaving cloth, cooking, preparing fields, planting seeds, harvesting, weeding, and carrying water. Men would weed, plow, help with harvest, carry firewood, build houses, herd llamas and alpacas, and sometimes spin and weave. This meant that genders worked together to complete tasks. Spanish observers sometimes thought women were treated like slaves because women in Spanish society did not work in fields. Women were sometimes allowed to own land and animals because inheritance came from both the mother's and father's side of the family.

Burial Customs

The ancient Incas learned to mummify their dead. They did this to show respect to their leaders. Mummification helped preserve the body so others could worship them after death. The ancient Inca believed in reincarnation, so keeping the body intact was important for going to the afterlife. Mummification was mainly for royalty. The Incas used different methods to mummify bodies. They used Chicha corn beer to slow down decay. Bodies were stuffed with natural materials like plants and animal hair. Sticks were used to keep their shape. After mummification, the Inca would bury their dead in a curled-up position inside a vessel, preparing them for a new birth. A ceremony with music, food, and drink was held for the family and loved ones.

Inca Religion

Inca myths were passed down by word of mouth. Later, early Spanish colonists wrote them down. Some scholars think they were also recorded on quipus, the knotted string records.

The Inca believed in reincarnation. They thought that after death, the journey to the next world was difficult. The spirit of the dead, camaquen, needed to follow a long road. A black dog that could see in the dark was needed to help on this trip. Most Incas imagined the afterlife as a paradise with flower-covered fields and snowy mountains.

It was important to the Inca that they not die by burning. They also believed that the body of the dead should not be burned. Burning would make their life force disappear and stop their journey to the afterlife. Inca nobles practiced cranial deformation. They wrapped tight cloth straps around the heads of newborns to shape their soft skulls into a cone. This helped show who was noble and who was not.

The Incas did perform human sacrifices. For example, when the Inca leader Huayna Capac died in 1527, many servants and officials were killed.

Inca Gods and Goddesses

The Incas believed in many gods and goddesses. These included:

- Viracocha (also Pachacamac) – The creator of all living things.

- Inti – The sun god and special god of the holy city of Cusco.

- Mama Killa – Wife of Inti, called Moon Mother.

- Pachamama – The Earth Goddess and wife of Viracocha. People gave her offerings and prayed to her for good harvests.

- Apu Illapu – The Rain God, prayed to when rain was needed.

- Ayar Cachi – A hot-tempered God who caused earthquakes.

- Illapa – Goddess of lightning and thunder.

- Kuychi – The Rainbow God, linked with fertility.

- Mama Occlo – Taught people wisdom, how to weave, and build houses.

- Manco Cápac – Known for his bravery. He was sent to earth to be the first king of the Incas. He taught people how to farm, make weapons, work together, and worship the gods.

- Quchamama – Goddess of the sea.

- Sachamama – Means Mother Tree, a goddess shaped like a two-headed snake.

- Yakumama – Means Mother Water. Represented as a snake. When she came to earth, she turned into a great river.

Inca Economy

The Inca Empire traded with outside regions. Most households had to pay taxes. This was usually done through mit'a (mandatory public service) and military duties. However, bartering (trading goods directly) also happened in some areas. In return, the state provided safety and food during hard times from emergency supplies. They also built farming projects like aqueducts and terraces to grow more food. Inca officials sometimes hosted parties for their people. While mit'a was used by the state for labor, villages also had an older system of community work called mink'a. This system still exists today.

Inca Government

Inca Beliefs and Leadership

The Sapa Inca (the emperor) was seen as divine. He was the head of the state religion. The Willaq Umu (Chief Priest) was second to the emperor. Local religious traditions continued. Some, like the Oracle at Pachacamac, were even officially respected. After Pachacuti, the Sapa Inca claimed to be a descendant of Inti, the sun god. He was "son of the sun," and his people were "children of the sun." His right to rule and his mission to conquer came from this holy ancestor. The Sapa Inca also led important festivals, especially the Inti Raymi, or "Sunfest." This festival started on the June solstice and ended nine days later. Cusco was considered the center of the universe.

How the Empire Was Organized

The Inca Empire was like a federal system. It had a main government with the Inca emperor at its head. It also had four large regions, or suyu: Chinchay Suyu (northwest), Anti Suyu (northeast), Kunti Suyu (southwest), and Qulla Suyu (southeast). The four corners of these regions met in the center, at Cusco. These suyu were probably created around 1460 during Pachacuti's rule. At that time, they were about the same size. Later, their sizes changed as the empire grew north and south.

Cusco was likely not a regular province. It was probably more like a special federal district, similar to Washington, D.C. today. The city was at the center of the four suyu and was the most important place for politics and religion. While Cusco was mainly ruled by the Sapa Inca and his family, each suyu was governed by an Apu. This was a title of respect for high-ranking men and sacred mountains. Both Cusco and the four suyu were divided into upper and lower sections. Since the Inca didn't have written records, we can't list all the provinces. However, old Spanish records show there were likely more than 86 provinces.

The Four Suyu

The most populated suyu was Chinchaysuyu. It included the former Chimu empire and much of the northern Andes. At its largest, it stretched through much of what is now Ecuador and Colombia.

Qullasuyu was the largest suyu by area. It was named after the Aymara-speaking Qulla people. It included what is now the Bolivian Altiplano and much of the southern Andes. It reached into what is now Argentina and as far south as the Maipo or Maule river in modern Central Chile.

Antisuyu was the second smallest suyu. It was northwest of Cusco in the high Andes mountains. Its name is where the word "Andes" comes from.

Kuntisuyu was the smallest suyu. It was along the southern coast of modern Peru and extended into the highlands towards Cusco.

Laws and Rules

The Inca did not have written laws. Instead, customs and traditions guided how people behaved. The state had legal power through officials called tokoyrikoq (meaning "he who sees all"), who were like inspectors. The highest inspector was usually a close relative of the Sapa Inca.

The Inca had three main rules that guided their behavior:

- Ama sua: Do not steal.

- Ama llulla: Do not lie.

- Ama quella: Do not be lazy.

How the Government Was Run

The Sapa Inca was at the top of the Inca government. He was helped by the Willaq Umu, who was the High Priest of the Sun. The Sapa Inca also had an assistant, the Inkap rantin, who was like a Prime Minister.

Starting with Topa Inca Yupanqui, the Sapa Inca was helped by a Council of the Realm. This council had 16 nobles, who were the governors of the empire's provinces.

Men of a certain age were organized into groups for mit'a service (mandatory public work). Each group of more than 100 men was led by a kuraka. Smaller groups were led by a kamayuq, who had a lower status that was not passed down through family.

| Kuraka in Charge | Number of Taxpayers |

|---|---|

| Hunu kuraka | 10,000 |

| Pichkawaranqa kuraka | 5,000 |

| Waranqa kuraka | 1,000 |

| Pichkapachaka kuraka | 500 |

| Pachaka kuraka | 100 |

| Pichkachunka kamayuq | 50 |

| Chunka kamayuq | 10 |

Inca Arts and Technology

Amazing Architecture

Architecture was the most important of the Inca arts. The most famous example is Machu Picchu, built by Inca engineers. The main Inca buildings were made of stone blocks that fit together so perfectly that you couldn't even fit a knife blade between them. These buildings have lasted for centuries without any mortar (cement) to hold them together.

This building method was first used by the Pukara people (around 300 BC–AD 300) near Lake Titicaca. Later, it was used in the city of Tiwanaku (around AD 400–1100) in modern-day Bolivia. The rocks were shaped to fit exactly by repeatedly lowering one rock onto another. They would then carve away any parts of the bottom rock where dust was squished. This tight fit and the curved shape of the bottom rocks made them incredibly strong. They could even survive earthquakes and volcanoes.

Measures, Calendars, and Math

The Inca used parts of the human body for measurements. Units included fingers, the distance from thumb to forefinger, palms, and arm spans. The basic unit for distance was thatkiy, or one pace. The next largest unit was the topo or tupu, which was about 6,000 paces (around 4.0 to 6.3 km). The wamani was made of 30 topos (about 232 km). For measuring area, they used 25 by 50 arm spans, measured in topos (about 3280 square km). It seems that distance was often thought of as one day's walk.

Inca calendars were closely linked to astronomy. Inca astronomers understood equinoxes (when day and night are equal), solstices (longest/shortest days), and the Venus cycle. However, they could not predict eclipses. The Inca had a solar and a lunar calendar. Each lunar month had festivals and rituals. Days were not named, and days were not grouped into weeks. Months were not grouped into seasons. Time during a day was measured by how far the sun had moved or how long it took to do a task.

Numbers and information were stored in the knots of quipu strings. This allowed them to store large numbers in a small space. These numbers were stored in a base-10 system, just like the Quechua language and their administrative units. These numbers, stored in quipu, could be calculated on yupanas. These were grids with squares that had different mathematical values, possibly working like an abacus. Calculations were done by moving piles of tokens, seeds, or pebbles between the compartments of the yupana. It is likely that Inca math allowed for division and multiplication.

Tunics and Textiles

Tunics were made by skilled Inca textile makers as warm clothing. They also showed a person's cultural and political status and power. Cumbi was a fine, woven woolen cloth used to make tunics. Both specially chosen women and men made Cumbi. In general, both men and women practiced textile making.

Complex patterns and designs on tunics showed information about order in Inca society and the universe. Tunics could also show a person's connection to ancient rulers or important ancestors. Many tunics had a "checkerboard effect" called the collcapata. Rulers wore different tunics throughout the year for various events and feasts.

Uncu

Uncu was a men's garment, like a knee-length tunic. Royals wore it with a mantle cloth called yacolla.

Ceramics, Metals, and Textiles

Inca ceramics were painted using many colors. They showed animals, birds, waves, felines (big cats), and geometric patterns. In a culture without a written language, ceramics showed everyday life. This included melting metals, relationships, and tribal wars. The most unique Inca ceramic objects are the Cusco bottles, or "aryballos." Many of these pieces can be seen in museums in Lima.

Sadly, almost all of the gold and silver work of the Inca empire was melted down by the conquistadors. It was then shipped back to Spain.

Communication and Medicine

The Inca recorded information on knotted strings called Quipu. We can no longer understand them today. Quipus are also believed to have recorded history and literature.

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine. They successfully performed skull surgery. They cut holes in the skull to relieve fluid buildup and swelling from head wounds. Many of these surgeries were successful. Survival rates were 80–90%, much higher than before Inca times (about 30%).

Coca Plant Use

The Incas thought the coca plant was sacred and magical. Its leaves were used in small amounts to reduce hunger and pain during work. But they were mostly used for religious and health reasons. The Chasqui, who were messengers running across the empire, chewed coca leaves for extra energy. Coca leaves were also used as an anesthetic during surgeries.

Weapons, Armor, and Warfare

The Inca army was very powerful for its time. Any ordinary villager or farmer could be called to be a soldier as part of the mit'a system (mandatory public service). Every able-bodied Inca male of fighting age had to take part in war at least once. They also had to be ready for war again when needed. When the empire was at its largest, every part of the empire helped create an army for war.

The Incas had no iron or steel. Their weapons were not much stronger than those of their enemies. So, they often won by having many more soldiers. Or, they would persuade enemies to surrender by offering good terms. Inca weapons included hardwood spears thrown with throwers, arrows, javelins, slings, bolas (stones tied together), clubs, and maces with star-shaped heads made of copper or bronze. Rolling rocks downhill onto the enemy was a common strategy, using the hilly land to their advantage. Fighting was sometimes joined by drums and trumpets made of wood, shell, or bone. Armor included:

- Helmets made of wood, cane, or animal skin, often lined with copper or bronze. Some had feathers.

- Round or square shields made from wood or animal hide.

- Cloth tunics padded with cotton and small wooden planks to protect the spine.

- Ceremonial metal chest plates, made of copper, silver, and gold, have been found in burial sites. Some might have been used in battle.

Roads allowed the Inca army to move quickly on foot. Shelters called tambo and storage buildings called qullqas were built one day's travel distance from each other. This meant an army on a campaign could always be fed and rested. This can be seen in names of ruins like Ollantay Tambo, which means "My Lord's Storehouse." These were set up so the Inca ruler and his group would always have supplies and shelter ready when they traveled.

Adapting to High Altitudes

The people of the Andes, including the Incas, adapted to living in high mountains. They developed larger lung capacity, having about 2 liters (4 pints) more blood volume. They also had more hemoglobin, a protein that carries oxygen from the lungs to the body.

Compared to other humans, the Andean people had slower heart rates.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Imperio incaico para niños

In Spanish: Imperio incaico para niños

Inca Archeological Sites

Related to the Inca

- History of Cusco

- Atahualpa, last Inca Emperor

- Aclla, the "chosen women"

- Amauta, Inca teachers

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- Anden, agricultural terrace

- Inca army

- Inca cuisine

- Incan aqueducts

- Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala

- Paria, Bolivia

- Religion in the Inca Empire

- Tampukancha, Inca religious site

- Society of the Spanish-Americans in the Spanish Colonial Americas