History of Kashmir facts for kids

The history of Kashmir is a long story connected to the larger Indian subcontinent in South Asia. It also has influences from nearby regions like Central and East Asia.

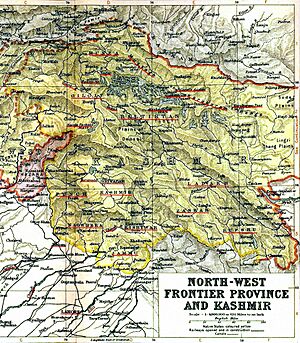

Long ago, Kashmir usually meant only the Kashmir Valley in the western Himalayas. But today, it refers to a much bigger area. This includes parts controlled by India (the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh), parts controlled by Pakistan (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan), and parts controlled by China (Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract).

In the first half of the 1st millennium CE, Kashmir became a key place for Hinduism. Later, under the Maurya and Kushana rulers, it became important for Buddhism. Around the 9th century, during the Karkota Dynasty, a special type of Shaivism (a Hindu tradition) began there. This flourished for about 700 years under Hindu kings, ending in the mid-14th century.

The spread of Islam in Kashmir started in the 13th century. It grew quickly under Muslim rulers in the 14th and 15th centuries. This led to Kashmir Shaivism becoming less popular.

In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, starting the Shah Mir dynasty. For the next five centuries, Muslim kings ruled Kashmir. This included the Mughal Empire (1586-1751) and the Afghan Durrani Empire (1747-1819). In 1819, the Sikhs, led by Ranjit Singh, took over Kashmir.

After the Sikh defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1846, the Treaty of Lahore was signed. Then, the British East India Company sold the region to Gulab Singh, the Raja of Jammu, through the Treaty of Amritsar. Gulab Singh became the new ruler of Kashmir. His family ruled under British guidance until 1947. After that, the former princely state became a disputed area, now managed by India, Pakistan, and China.

Contents

What does "Kashmir" mean?

People often say the name "Kashmir" means "dried land." This comes from the old Sanskrit words ka (water) and shimīra (desiccate).

In the Rajatarangini, a history of Kashmir written around the mid-12th century by Kalhana, it says that the Kashmir Valley used to be a big lake. According to Hindu stories, a great sage named Kashyapa drained this lake. He did this by cutting a gap in the hills at Baramulla. After the lake was drained, Kashyapa asked Brahmins (Hindu priests) to live there. This story is still a local tradition. The main town in the valley was called Kashyapa-pura, which some think is the same as Kaspapyros mentioned by ancient Greek writers.

How do we know about Kashmir's history?

The Nilamata Purana (written around 500–600 CE) tells us about Kashmir's early history. However, it's an old religious text, so some parts might not be completely accurate.

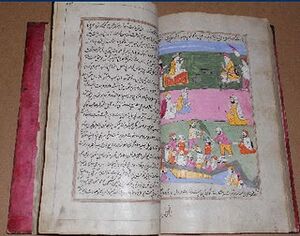

A very important book is Kalhana's Rajatarangini (meaning "River of Kings"). This book, finished by 1150 CE, tells the history of Kashmir's rulers from ancient times up to the 12th century. Kalhana used old stories, inscriptions (writings on stone), coins, and monuments to write his history. He is often called "India's first historian" because he tried to analyze events carefully.

Later, during the time of Muslim kings in Kashmir, three more books were written to continue the Rajatarangini story. These books end with the Mughal emperor Akbar taking over Kashmir in 1586 CE. Other important books from the Sultanate period include Baharistan-i-Shahi and Haidar Mailk's Tarikh-i-Kashmir.

Early History of Kashmir

The oldest human settlements in the Kashmir Valley date back to about 3000 BCE. The most important of these is Burzahom. Here, people lived in pit dwellings (holes in the ground) and used stone tools. Later, they built houses on the ground and buried their dead, sometimes with animals. They hunted, fished, and also grew wheat, barley, and lentils.

Around 326 BCE, King Porus asked Abisares, the king of Kashmir, to help him fight Alexander the Great. After Porus lost, Abhisares gave gifts to Alexander.

During the rule of Ashoka (304–232 BCE), Kashmir became part of the Maurya Empire. This is when Buddhism came to Kashmir. Many stupas (Buddhist shrines) and the city of Srinagari (Srinagar) were built then.

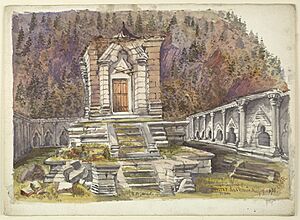

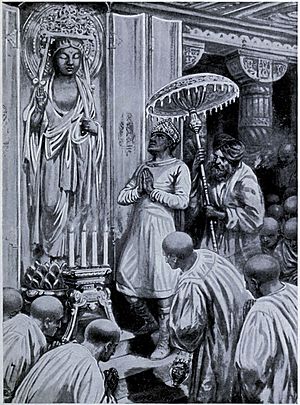

Kanishka (127–151 CE), an emperor of the Kushan dynasty, conquered Kashmir. He built a new city called Kanishkapur. Buddhist stories say Kanishka held the Fourth Buddhist council in Kashmir, where famous scholars like Ashvagosha and Nagarjuna took part. By the 4th century, Kashmir was a center for both Buddhism and Hinduism. Kashmiri Buddhist missionaries helped spread Buddhism to Tibet and China. Pilgrims from these countries started visiting Kashmir from the 5th century CE. A famous Kashmiri scholar, Kumārajīva, traveled to China and helped translate many Sanskrit books into Chinese.

The Alchon Huns, led by Toramana, crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and conquered parts of western India, including Kashmir. His son, Mihirakula, tried to conquer all of North India. After being defeated, Mihirakula returned to Kashmir and took over the kingdom. He then conquered Gandhara, where he destroyed many Buddhist shrines. The Huns' power faded after Mihirakula's death.

Hindu Dynasties

Hindu dynasties ruled Kashmir from the 7th to the 14th centuries. During this time, Kashmiri Hinduism saw big changes. Kashmir produced many poets, thinkers, and artists who contributed to Sanskrit literature and Hindu religion. One important scholar was Vasugupta (c. 875–925 CE), who wrote the Shiva Sutras. These writings formed the basis for Kashmir Shaivism, a unique Hindu philosophy. Another great scholar, Abhinavagupta (c. 975–1025 CE), wrote many books on Kashmir Shaivism, which became popular among the people.

In the 8th century, the Karkota Empire became the rulers of Kashmir. Kashmir grew into a powerful empire under them. One of their rulers, Chandrapida, was even recognized by the Chinese emperor. His successor, Lalitaditya Muktapida, led successful military campaigns against Tibetans and other kingdoms in India. He even defeated Arabs in Sindh. After Lalitaditya's death, Kashmir's influence decreased, and the dynasty ended around 855–856 CE.

The Utpala dynasty, founded by Avantivarman, followed the Karkotas. His successor, Shankaravarman, had a successful military campaign in Punjab. In the 10th century, political problems made the royal bodyguards (Tantrins) very powerful. This led to chaos until they were defeated. Queen Didda, whose mother was from the Hindu Shahi family, ruled in the second half of the 10th century. She is known for building a canal called "Kutte Kol" to stop floods in Srinagar. After her death in 1003 CE, the Lohara dynasty took over.

Suhadeva, the last king of the Lohara dynasty, fled Kashmir after Zulju, a Turkic–Mongol chief, attacked Kashmir. His wife, Queen Kota Rani, ruled until 1339.

In the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni tried twice to conquer Kashmir, but he failed to capture the fortress at Lohkot.

Muslim Rulers

Kashmir Sultanate (1346–1580s)

Historians say that high taxes, corruption, and fights among nobles during the Lohara dynasty (1003–1320 CE) made Kashmir weak. This opened the way for foreign invasions. Rinchana, a Tibetan Buddhist refugee, became ruler after Zulju. Rinchana converted to Islam, possibly for political reasons, as he needed the support of Kashmiri Muslims. His minister, Shah Mir, later took over, starting Muslim rule and the Shah Mir dynasty in Kashmir.

In the 14th century, Islam slowly became the main religion in Kashmir. With this change, Sanskrit literature in Kashmir became less common. A Muslim preacher named Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani, also known as Nund Rishi, mixed ideas from Kashmir Shaivism with Sufi mysticism.

Most Sultans between 1354 and 1470 CE were tolerant of other religions. However, Sultan Sikandar (1389–1413 CE) was an exception. He taxed non-Muslims, forced some conversions, and was called But–Shikan (idol-breaker) for destroying idols.

Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (c. 1420–1470 CE) was different. He invited artists and craftspeople from Central Asia and Persia to teach local artists. Under his rule, arts like wood carving, papier-mâché, and shawl and carpet weaving grew. For a short time in the 1470s, areas like Jammu and Poonch revolted against the Sultan, but they were brought back under control.

By the mid-16th century, Hindu influence in the courts declined. Muslim missionaries came from Central Asia and Persia, and Persian replaced Sanskrit as the official language. Around the same time, the powerful Chaks took over from the Shah Mir dynasty.

The Mughal general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat invaded Kashmir around 1540 CE for Emperor Humayun. However, he was overthrown due to persecution of different Muslim groups and encouragement from the Suri kings.

Mughals (1580s–1750s)

Kashmir came under direct Mughal rule when Emperor Akbar the Great took control in 1586. Later, Shah Jahan made Kashmir a separate province with its capital in Srinagar. During the Mughal rule, many beautiful gardens, mosques, and palaces were built.

Religious intolerance and unfair taxes returned when Mughal emperor Aurangzeb became ruler in 1658 CE. After his death, the Mughal Empire's power weakened.

In 1700 CE, a holy relic of Muhammad (the Mo-i Muqqadas) was brought to Kashmir. It was placed in the Hazratbal Shrine by Dal Lake. The invasion of India by Nadir Shah in 1738 CE further weakened Mughal control over Kashmir.

Durrani Empire (1752–1819)

The Afghan Durrani Empire, led by Ahmad Shah Durrani, took control of Kashmir in 1752, taking advantage of the weakening Mughal Empire. In the mid-1750s, the Afghan governor of Kashmir, Sukh Jiwan Mal, rebelled but was defeated in 1762. After this, the Durrani rulers were harsh, forcing conversions and imposing heavy taxes on everyone, regardless of religion.

Afghan governors managed Kashmir for the Durrani Empire. The income from Kashmir was a big part of the Durrani Empire's money. The empire controlled Kashmir until 1819, when the Sikh Empire took it over.

Sikh Rule (1820–1846)

After four centuries of Muslim rule, Kashmir was conquered by the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh of Punjab in 1819, after the Battle of Shopian. At first, Kashmiris welcomed the new Sikh rulers because they had suffered under the Afghans. However, the Sikh governors were also very strict. Sikh rule was generally seen as harsh, partly because Kashmir was far from the Sikh capital in Lahore.

The Sikhs made several anti-Muslim laws. For example, killing a cow could lead to a death sentence. They also closed the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar and banned the azaan (the public Muslim call to prayer). European visitors to Kashmir at this time wrote about the extreme poverty of the many Muslim farmers and the very high taxes under the Sikhs. Some reports said that high taxes had made many areas empty, with only a small part of the land being farmed. However, after a famine in 1832, the Sikhs lowered the land tax to half the produce and offered interest-free loans to farmers. Kashmir then became the second-highest source of income for the Sikh empire. During this time, Kashmiri shawls became famous worldwide.

Earlier, in 1780, the kingdom of Jammu (south of the Kashmir valley) was also taken by the Sikhs. Gulab Singh, a grandnephew of the former ruler of Jammu, joined Ranjit Singh's court. He proved himself in battles and was made the Raja of Jammu in 1820. With the help of his officer, Zorawar Singh, Gulab Singh soon captured Ladakh and Baltistan for the Sikhs.

Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (Dogra Rule, 1846–1947)

In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War began. Gulab Singh stayed neutral until the battle of Sobraon (1846), where he helped as a mediator between the Sikhs and the British. Two treaties were signed. In the first, the State of Lahore gave the British land between the Beas and Indus rivers for 10 million rupees. In the second, called the Treaty of Amritsar, the British gave Gulab Singh all the hilly land east of the Indus and west of the Ravi (which included the Vale of Kashmir) for 7.5 million rupees. This treaty freed Gulab Singh from his duties to the Sikhs and made him the Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Dogra rulers were loyal to the British during the revolt of 1857 in India. They helped the British, and in return, the British ensured that Dogra rule would continue in Kashmir. Soon after Gulab Singh's death in 1857, his son, Ranbir Singh, added the areas of Hunza, Gilgit, and Nagar to the kingdom.

The Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu was formed between 1820 and 1858. It was a mix of different regions, religions, and ethnic groups. To the east, Ladakh had Tibetan people and practiced Buddhism. To the south, Jammu had a mix of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. In the central Kashmir valley, most people were Sunni Muslim, but there was a small but important Hindu minority called Kashmiri pandits. To the northeast, sparsely populated Baltistan had people related to Ladakhis but who practiced Shi'a Islam. To the north, Gilgit Agency had diverse, mostly Shi'a groups. To the west, Punch was Muslim, but of a different ethnic group than the Kashmir valley.

Even though Muslims were the majority, they faced harsh treatment under Hindu rule. This included high taxes, unpaid forced labor, and unfair laws. Many Kashmiri Muslims moved from the Valley to Punjab because of famine and the Dogra rulers' policies. The Muslim farmers were poor and lacked education. They were often in debt to landlords and moneylenders. They did not form political groups until the 1930s.

1947

Ranbir Singh's grandson, Hari Singh, became the ruler of Kashmir in 1925. He was the monarch in 1947 when British rule ended in India and the country was divided into Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan. An internal revolt started in the Poonch region against the Maharaja's high taxes. In August, the Maharaja's forces fired on people who wanted Kashmir to join Pakistan. They burned villages and killed innocent people. The Poonch rebels declared their own independent government of "Azad" Kashmir on October 24.

Rulers of Princely States were encouraged to join either India or Pakistan. They were supposed to consider things like how close their state was to each country and what their people wanted. In 1947, Jammu and Kashmir's population was about 77% Muslim and 20% Hindu. To avoid making a quick decision, the Maharaja signed a standstill agreement with Pakistan. This agreement kept trade, travel, and communication going between Kashmir and Pakistan. An agreement with India was still being discussed.

After big riots in Jammu, in October 1947, Pashtuns from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province invaded Kashmir. They were recruited by the Poonch rebels and were reportedly angry about the violence against Muslims in Poonch and Jammu. The tribesmen looted and killed people along the way. Their goal was to scare Hari Singh into giving up. Instead, the Maharaja asked the Government of India for help. The Governor-General Lord Mountbatten agreed, but only if the ruler joined India.

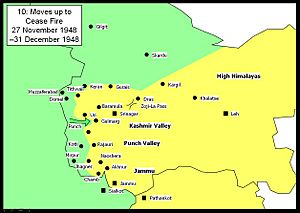

Once the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession, Indian soldiers entered Kashmir. They pushed the Pakistani-supported fighters out of most of the state. India accepted Kashmir's joining, saying it was temporary until the people's wishes could be known. Kashmir leader Sheikh Abdullah supported this joining, saying the people of the state would make the final decision. He was made the head of the emergency government by the Maharaja. The Pakistani government immediately said the joining was not real, claiming the Maharaja was forced and had no right to sign with India while the agreement with Pakistan was still active.

After 1947

In early 1948, India asked the United Nations to help resolve the Kashmir conflict. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on April 21, 1948, setting up a commission. The UN said that the people of Jammu and Kashmir must decide their future. India's Prime Minister at the time reportedly urged the UN to hold a vote in Kashmir. However, India insisted that no vote could happen until all foreign fighters were out of the state.

On January 5, 1949, a UN resolution stated that Kashmir's future (joining India or Pakistan) would be decided by a free and fair vote. Both countries agreed that Pakistan would withdraw its fighters, followed by the withdrawal of Pakistani and Indian forces. Then, a vote would be held. However, they could not agree on the details of how to remove the forces, so the vote never happened.

In late 1948, a ceasefire was agreed upon with the UN's help. But since the vote demanded by the UN never happened, relations between India and Pakistan worsened. This led to three more wars over Kashmir in 1965, 1971, and 1999. India controls about half of the original princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan controls a third, governing it as Gilgit–Baltistan and Azad Kashmir.

The UN Security Council passed Resolution 39 on January 20, 1948, to investigate the conflict. Later, Resolution 47 on April 21, 1948, ordered Pakistan's army to leave Jammu and Kashmir. It also said that Kashmir's joining India or Pakistan should be decided by a UN-supervised vote. However, India did not hold the vote, and no punishment was taken because the resolution was not binding. Also, the Pakistani army never left the part of Kashmir they held at the end of the 1947 war. They were required by the UN resolution to remove all armed personnel from Azad Kashmir before the vote.

The eastern part of the former princely state of Kashmir also has a border dispute. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some border agreements were signed between Great Britain, Afghanistan, and Russia about Kashmir's northern borders. But China never accepted these agreements. By the mid-1950s, the Chinese army had entered the northeast part of Ladakh. By 1956–57, they had built a military road through the Aksai Chin area. India's discovery of this road later led to border clashes and the Sino-Indian war in October 1962. China has occupied Aksai Chin since 1962. Also, Pakistan gave an area called the Trans-Karakoram Tract to China in 1965.

In 1949, the Indian government asked Hari Singh to leave Jammu and Kashmir. Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the National Conference Party, took over the government. Since then, India and Pakistan have had a strong disagreement, leading to three wars over Kashmir. The ongoing dispute and problems with democracy also led to the rise of Kashmiri nationalism and armed groups in the state.

In 1986, the Anantnag riots happened after the Chief Minister ordered a mosque to be built at a Hindu temple site in Jammu. These riots were also part of bigger Hindu-Muslim riots happening in other states. After the 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election, which many felt were unfair, some unhappy Kashmiri youth joined the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front(JKLF). This group became an alternative to the ineffective democratic system. This led to a rise in popular uprising in the Kashmir Valley. In 1989, the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir became more intense as fighters from Afghanistan entered the region after the end of the Soviet–Afghan War. Pakistan provided weapons and training to both local and foreign fighters in Kashmir, making the unrest worse.

In August 2019, the Government of India removed the special status given to Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian constitution. The Parliament of India passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act. This law divided the state into two union territories: Jammu and Kashmir in the west and Ladakh in the east. These changes took effect on October 31, 2019.

Historical Population of Kashmir

In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, the total population of the princely state of Kashmir was 2,905,578. Of these, 2,154,695 were Muslims, 689,073 Hindus, 25,828 Sikhs, and 35,047 Buddhists. Most Hindus lived in Jammu, where they were a little less than 50% of the population. In the Kashmir Valley, Hindus were only about 5.24% of the population. These percentages have stayed mostly the same for the last 100 years. In the 1941 Census, Muslims were 93.6% of the Kashmir Valley population, and Hindus were 4%. In 2003, Muslims in the Kashmir Valley were 95%, and Hindus were 4%. In Jammu, Hindus were 67%, and Muslims were 27% in the same year.

Among the Muslims in the Kashmir province, there were four main groups: Shaikhs, Saiyids, Mughals, and Pathans. The Shaikhs were the most numerous. They were descendants of Hindus but had lost their old caste rules. They had clan names called krams, like "Tantre", "Shaikh", "Bat", "Mantu", "Ganai", "Dar", "Damar", and "Lon". The Saiyids were either religious leaders or farmers. Their kram name was 'Mir'. The Mughals were not many, with kram names like "Mir" (from "Mirza"), "Beg", "Bandi", "Bach", and "Ashaye". The Pathans were more numerous than the Mughals and lived mainly in the southwest of the valley. Some Pathan groups, like the Kuki-Khel Afridis at Dranghaihama, kept their old customs and spoke Pashtu. Other main Muslim groups in the princely state included the Butts, Dar, Lone, Jat, Gujjar, Rajput, Sudhan, and Khatri. These groups are native to the princely state and converted to Islam from Hinduism.

Among the Hindus in Jammu province, the most important groups recorded in the census were Brahmans, Rajputs, Khattris, and Thakkars.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Cachemira para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Cachemira para niños

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 47

- Kashmiriyat

- Sharada Peeth

- Buddhism in Kashmir

- Harsha of Kashmir

- List of topics on the land and the people of "Jammu and Kashmir"

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |