History of Jersey facts for kids

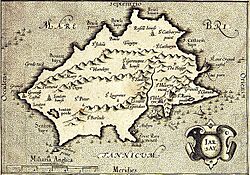

Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands, became an island about 6,000 years ago. People lived here very early on, leaving behind ancient monuments and hidden treasures. In the 900s, Jersey became part of Normandy, a region in France. When the Normans conquered England in the 1000s, Jersey stayed connected to Normandy. However, in the 1200s, Normandy and England split. The Channel Islands, including Jersey, chose to remain loyal to the English Crown. This decision politically separated Jersey from mainland Normandy.

Because English kings still claimed Normandy, Jersey kept its Norman laws and government style. This led to Jersey becoming a self-governing Crown Dependency. For centuries, from the 1000s to the 1400s, Jersey was often on the front lines of wars between England and France.

During the Tudor period (1485-1603), the English Crown broke away from the Roman Catholic Church. Many French religious refugees, called Huguenots, moved to Jersey. This led to Calvinism becoming the main religion on the island. In 1617, the King's special council, the Privy Council, clearly separated the powers of the Governor (military leader) and the Bailiff (justice and civil leader). The Bailiff was given full control over justice and everyday island matters. During the English Civil War, Jersey mostly supported the King, thanks to the powerful de Carteret family. However, forces loyal to Parliament eventually captured the island. After the King returned to power, the de Carterets were given land in the American colonies. They named this new land New Jersey.

In the 1700s, Jersey faced some local problems, including the Corn Riots in 1769. These riots led to big changes in 1771. The island's parliament, called the States, gained more power to make laws. The Royal Court lost its law-making abilities. For much of the 1800s, island politics was divided between two main groups, the Magot and Charlot parties. In 1781, the French tried to invade Jersey. However, they were defeated by an army led by Major Francis Peirson in the famous Battle of Jersey. After 1815, peace with France meant Jersey was no longer as important militarily. Better transport links made the island closer to the United Kingdom. This, along with a growing sense of British nationalism, caused Jersey's culture to become much more English, or anglicised. Before this, it had kept many Norman-French traditions.

Jersey was not directly involved in the fighting of the First World War. However, during the Second World War, the Channel Islands were the only part of the British Isles occupied by enemy forces. From 1940 to 1945, German forces occupied Jersey. The island was freed on May 9, 1945. This day is still celebrated as Jersey's national day. After the war, Jersey became a popular place for tourists. It also grew into a major offshore finance centre, a place where international money business happens.

Contents

- Island's Name: What Does Jersey Mean?

- Ancient Times: Jersey's First People

- Early History: Romans, Christians, and Normans

- The 1200s: Jersey Becomes Independent

- The 1300s and 1400s: Wars and Changes

- The 1600s: Power Shifts and Civil War

- The 1700s: Unrest and Battles

- The 1800s: Big Changes in Society

- The 1900s: Wars, Reforms, and Finance

- See also

Island's Name: What Does Jersey Mean?

Jersey was part of the Roman Empire a long time ago. We don't have much information about the island during Roman times or the early Middle Ages. People used to think the Romans called the island Caesarea. However, some historians now believe Caesarea might have been the Isles of Scilly off England. Another Roman name, Andium, is often linked to Jersey. So, Jersey might have been Andium, and another island like the Minquiers might have been Caesarea.

The name "Jersey" itself is thought to come from Norse, a language spoken by Vikings. The "-ey" part means "island." The "Jer-" part might come from "Caesar," meaning "Caesar's island." Another idea is that it means "Geirr's Island," from a Norse name Geirr, or "the grassy isle" from an old Frisian word.

Ancient Times: Jersey's First People

The very first signs of people living in Jersey date back about 250,000 years. This was during the Middle Paleolithic period, before Jersey became an island. Back then, groups of Neanderthal hunters used caves like La Cotte de St Brelade. They used these caves as a base to hunt large animals like mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses.

Around 6,000 years ago, rising sea levels turned Jersey into an island. Evidence shows that modern humans, Homo sapiens, lived here at least 12,000 BC. They left behind ancient engravings.

Later, in the Neolithic period, settled communities built large stone burial sites called dolmens. The many large dolmens, especially La Hougue Bie, suggest that many people worked together to build them. This shows there was good social organization across a wide area. Archeological finds also show that Jersey traded with Brittany (France) and southern England during this time.

Hidden Treasures: Hoards Discovered

Many valuable items have been found in Jersey, showing that people lived and thrived here. In 1889, a 746-gram gold necklace, called a torc, from Ireland was found while a house was being built in Saint Helier. In 1976, a Bronze Age collection of 110 tools, mostly spears and swords, was discovered in Saint Lawrence. This was probably a metalworker's collection.

Large collections of coins have also been found. In 2012, two people using metal detectors found what might be Europe's biggest collection of ancient coins. This was the Grouville Hoard, with 70,000 Iron Age and Roman coins. It's believed these coins belonged to a tribe fleeing Julius Caesar's armies around 50-60 BC. Another Bronze Age collection, the Trinity Hoard, was found in 2012.

Early History: Romans, Christians, and Normans

Historians believe Romans might have occupied Jersey, even though there's no direct proof. Roman coins have been found on the north coast. Some sites, like Caesar's fort at Mont Orgueil, are linked to the Romans. Roman influence is also seen at Le Pinacle, where remains of a simple structure suggest Gallo-Roman temple worship.

When the Roman emperor Augustus Caesar divided Gaul (modern France) into provinces, Jersey was part of the province based in Lyons. Roman culture had a strong impact on Jersey. It brought Latin, which later developed into French and Jèrriais, the local language. It also influenced English.

Around the 5th and 6th centuries AD, people called Britons moved from Britain to Brittany. It's thought they also settled the Channel Islands. This likely brought Christianity to Jersey. Saints like Samson of Dol and Branwalator (Brelade) were active in the area. Tradition says Saint Helier from Belgium first brought Christianity to the island in the 500s.

Norman Rule: Becoming Part of Normandy

From 873, Jersey was affected by the conquests of the Normans along the western coast of France. The Channel Islands were part of the Kingdom of France at this time. Around 933, Duke William I, also known as William Longsword, took control of Jersey. Before this, Jersey had been linked to Brittany. It's likely that the Norman way of government and life replaced the older systems at this point. The island adopted the Norman law system, which is still the basis of Jersey law today. Under Norman rule, Jersey recovered from Viking attacks and developed its agriculture. People moving from mainland Normandy brought the cultural influences still seen on the island.

An important part of Jersey's early government was the fief. This system, which started with the Normans, provided a basic structure for rural life. Landlords, called Seigneurs, owned large areas of land. Most islanders were tenants who worked the land and owed payments and services to their Seigneurs. The de Carteret family, who held the most important fief of St Ouen, became very powerful. They settled on the island after losing their lands in France when King John lost Normandy.

In 1066, Duke William the Conqueror won the Battle of Hastings and became King of England. However, he continued to rule his French lands, including Jersey, separately. After his death, his sons split his lands. Later, Henry I reunited England and Normandy. So, Jersey became part of the English King's lands, but still part of Normandy and France.

By 1180, Jersey was divided into three main administrative areas. Most of the island's parish churches were built or rebuilt in the Norman style around this time. The boundaries of the parishes were set firmly and have mostly stayed the same since then.

After King Henry II and King Richard I, King John took the throne in 1199. In 1204, King Philip of France reconquered Normandy. Although the French occupied the Channel Islands for a short time, King John recognized their importance and got them back. Thanks to Pierre de Préaux, a governor who supported King John, the islands remained under the English King's personal control. They were described as a special possession of the Crown.

The 1200s: Jersey Becomes Independent

It is said that Jersey's self-rule comes from special rules given by King John. For centuries, English kings gave Jersey special rights and freedoms. This was probably to ensure the island's loyalty, as it was located right on the border with France. Since King John still claimed to be the Duke of Normandy, Jersey's courts were set up under Norman law, not English law. This is why Jersey's legal system is still based on old Norman laws and customs.

Now on the border between England and France, the Channel Islands became a key location. They were no longer a quiet place. In the early 1200s, the island was attacked by a pirate named Eustace the Monk. To protect Jersey, a castle called Mont Orgueil was built at Gorey. It became a royal fortress and military base.

King John needed to reorganize the land in Jersey because many landowners had their main estates in France. Most of these lords gave up their Jersey land. However, some, like the de Carteret family, stayed. This led to a new group of powerful landowners, who began to see themselves as islanders, not just Englishmen. This also firmly established the feudal system in Jersey, with fiefs led by Seigneurs.

In 1259, the Treaty of Paris (1259) officially separated the Channel Islands from mainland Normandy. The King of France gave up his claim to the islands. The King of England also gave up his claim to mainland Normandy. This meant the Channel Islands were never fully absorbed into the Kingdom of England. Jersey has had self-government ever since.

The island was governed by its own local government. The King appointed a Warden (later called "Governor" or "Lieutenant-Governor"). This person was mainly in charge of defending the island. The existing Norman customs and laws were allowed to continue. There was no attempt to bring in English law. The legal system was centralized, with the King of England as its head. Justice was carried out by 12 Jurats, Constables, and a Bailiff. These roles have different meanings and duties than in England.

In the late 1270s, Jersey got its own Bailiff. By the 1290s, the jobs of the Bailiff and the Warden were separated. The Warden was in charge of taxes and defense. The Bailiff was in charge of justice. This separation became permanent and is the basis for Jersey's modern system, where the Crown (represented by the Lieutenant-Governor) and justice are separate. The Bailiff became more involved with the community.

During the 1200s, Jersey became an important stop for ships carrying goods, especially wine. This led to a big economic boom. Islanders became very wealthy, and the population grew to about 12,000 people. This was more than the island's farms could feed on their own.

In 1294, King Philip IV of France attacked Jersey. This was part of a war and revenge for a French fleet being destroyed. Churches, homes, and crops were ruined, and many islanders died.

The 1300s and 1400s: Wars and Changes

Plague and the Hundred Years' War

In 1336, the Scottish king David Bruce attacked the Channel Islands. This attack, and the threat of more, led to the creation of an Island Militia in 1337. All men of military age had to join for the next 600 years. In November 1337, the Hundred Years' War began between England and France.

In March 1338, a French force landed on Jersey, aiming to capture the island. The French caused a lot of damage. They burned all the corn in four parishes. Although the island was taken over, Mont Orgueil castle remained in English hands. The French stayed until September, then left to conquer other islands. In 1339, the French returned with a large army. They promised islanders their old freedoms, which the English King had not recently confirmed. Some important islanders were pro-French at the time. Again, the French failed to take the castle and left after causing more damage.

In 1341, King Edward III rewarded the islanders for their efforts during the war. He declared that Jerseymen should keep all their special rights and customs. This started the tradition of English monarchs giving powers to islanders. This protected the Channel Islands' separate status from the rest of the King's lands.

In 1348, the terrible Black Death plague likely reached Jersey. There are no records, but it's thought that 30-40% of the population died. After the plague, the island's economy slowed down.

In July 1373, a French commander named Bertrand du Guesclin took over Jersey and attacked Mont Orgueil. His troops broke through the outer defenses. The castle's defenders agreed to surrender if no help arrived by a certain date. An English relief fleet arrived just in time.

In the 1390s, King Richard II wanted peace with France. He almost gave Jersey back to the French Crown. However, in 1394, he gave the islands the right to be free from tolls and customs duties in England.

This plan was stopped when Henry IV took the English throne in 1399. Henry confirmed Jersey's special rights. His tougher stance on France led to the war restarting. On October 7, 1406, a thousand French soldiers invaded Jersey. They landed at St Aubin's Bay and defeated the 3,000 defenders, but they couldn't capture the island. They then moved towards Mont Orgueil. An agreement was made: the island would pay a large ransom, and the French left on October 9.

In 1412, Henry V became king. He wanted to reclaim England's old lands in France. In 1413, Parliament ordered that all foreign-owned property be given to the Crown. This stopped payments to the French Church from Jersey. Instead, these payments went to the Crown. Jerseymen helped Henry in his successful campaigns against the French. By 1420, Henry had entered Paris. Jersey was no longer a distant outpost, leading to years of prosperity and the expansion of many parish churches.

From 1429, the French, inspired by Joan of Arc, began to push the English out of mainland France. This made Jersey a front-line island again. This event helped confirm Jersey's British identity. If England had not lost its French lands, France would likely have become the stronger part of the Anglo-French kingdom. Jersey, being so close to France, would probably have become part of France.

War of the Roses: French Occupation

During the Hundred Years' War, the French never managed to capture Jersey. However, during the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487) in England, Queen Margaret of Anjou made a secret deal with a French leader, Pierre de Brézé. This led to the French capturing Mont Orgueil in the summer of 1461. Jersey was occupied by French forces until 1468, when English forces and local militia recaptured the castle.

King Edward IV then separated the administrations of Jersey and Guernsey. He issued separate special rights for each island.

It's possible that the island's parliament, the States, was established during this French occupation. The French leader, Comte Maulevrier, confirmed the existing institutions. However, he also required that Jurats be chosen by the Bailiffs, Jurats, Rectors (church leaders), and Constables.

Tudors and Reformation: Religious Changes

The start of King Henry VII's reign in 1485 marked the "final separation" of the Channel Islands from Normandy. The long, war-torn relationship with Normandy finally ended. In 1496, Henry VII got permission from the Pope to move the islands from the French Bishop of Coutances to the English Bishop of Salisbury. However, for almost 50 years, the Bishop of Coutances continued to act as the islands' bishop due to their closeness.

In the 1500s, ideas of the Reformation spread. King Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church. This led islanders to adopt the Protestant religion. In 1569, Jersey's churches came under the control of the Diocese of Winchester in England. During King Edward VI's reign, a new English prayer book was translated into French. However, it didn't arrive until Queen Mary took the throne and brought Catholicism back to England. Jersey didn't have any death sentences for Catholicism, as its Governor kept the island out of the spotlight. The island didn't fully become Catholic, with many anti-Catholic people still in power.

During Queen Elizabeth I's reign, Calvinism became strong in Jersey. This was because many French Huguenot refugees moved to the island. Life became very strict: laws were enforced, punishments were severe, but education improved. Schools were started in every parish, and Jersey boys were supported to attend Oxford University. The excommunication of Elizabeth by the Pope increased the military threat to Jersey. New fortifications were needed because of the increasing use of gunpowder in battles. A new fortress, Elizabeth Castle, was built to defend St Aubin's Bay. It was named after the queen by Sir Walter Raleigh when he was governor. The island's militia was reorganized by parish. Each parish had two cannons, often kept in the church.

In 1540, the plague broke out on the island. The Lieutenant Governor ordered all markets, fairs, and public gatherings to close.

In 1541, the Privy Council planned to give Jersey two seats in the English Parliament. However, this never happened because the letter about it arrived too late.

Jersey's Role in Early Colonialism

During the time of Queen Elizabeth I, Europeans began exploring and setting up colonies in the Americas. Jerseymen were part of this. Jersey was an important trading port, linking the Netherlands to Spain and England to France. Many locals became colonists in Newfoundland after its discovery in 1497. By 1591, Jerseymen were sailing small boats across the Atlantic in spring and returning in autumn.

Jersey had good trade deals with England, especially for importing wool. England needed to export wool but was at war with most of Europe. The production of knitted goods in Jersey grew so much that it threatened the island's ability to grow its own food. So, laws were passed to control who could knit and when. The name "jersey" for a sweater shows how important this industry was.

The 1600s: Power Shifts and Civil War

Governors and Bailiffs: A Power Struggle

When James VI of Scotland became King of England (James I) in 1603, he also became King of Jersey. The Governor, Walter Ralegh, was imprisoned and replaced by Sir John Peyton. Peyton disliked Calvinism, the main religion in Jersey, and tried to get rid of it. The King initially allowed the islanders to keep their faith. However, Calvinism was becoming less popular among islanders, which helped Peyton.

In 1615, Jean Hérault was appointed Bailiff by the King. Peyton argued that the Governor should appoint the Bailiff. Hérault insisted the King had the right to appoint him directly. A special order from the Privy Council (dated August 9, 1615) supported Hérault. Hérault then claimed the Bailiff was the true head of government and the Governor was just a military officer. He even started wearing red robes, like English judges, to show his importance.

This argument led to a major change in Jersey's government. On February 18, 1617, the Privy Council clearly defined the powers of the Governor and Bailiff. It stated that "military forces be wholly in the Governor, and the care of justice and civil affairs in the Bailiff." This gave the Bailiff and the States (the island's parliament) power over justice and civil matters. This rule still limits the Lieutenant-Governor's involvement in local affairs today.

In 1617, Royal Commissioners visited the island. They suggested that Jersey should have a Dean, a church leader. David Bandinel was appointed Dean in 1620. This was not popular with the States. However, by order of the King, Anglicanism became the official religion of the island. The old Calvinist rules lost their power, and the Book of Common Prayer was used. All future ministers had to be appointed by a Bishop.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Jersey in Civil War

In the 1640s, England, Ireland, and Scotland were fighting in the War of the Three Kingdoms. This civil war also divided Jersey. Most islanders supported Parliament, but the de Carteret family, especially Sir George Carteret and Sir Philippe de Carteret II, held the island for the King. The Prince of Wales, who would become Charles II, visited the island in 1646 and again in 1649 after his father, Charles I, was executed. In St. Helier on February 17, 1649, Charles II was publicly declared king after his father's death. Parliamentarian forces eventually captured the island in 1651.

After the War: Commonwealth and Restoration

After the Parliamentarians won, Col. James Heane was appointed Governor of Jersey in 1651. Islanders complained about the new soldiers, who sometimes stole things and changed holy buildings. Many soldiers didn't respect church services because they couldn't understand the local French language. Jerseymen had to sign papers swearing loyalty to the "Republic of England... without King or House of Lords."

The new government wanted to change Jersey's system of government. At one point, only one Jurat remained in office. Parliament tried to control elections. Attempts were also made to make Jersey part of England. In 1653, it was even suggested that Jersey should send one member to the English Parliament. However, the States (Jersey's parliament) never met during the nine years of the Commonwealth. The Bailiff refused to call the Rectors.

Instead, the island was governed by the Royal Court. Oliver Cromwell, the English Lord Protector, directly appointed Jurats to the Court. However, many of them were absent.

When Charles II was declared King in London on May 8, 1660, the news reached Jersey on June 2. Charles II was proclaimed King for the second time in the Royal Square. To thank him for his help during his exile, Charles II gave George Carteret, the Bailiff and governor, a large amount of land in the American colonies. Carteret named this land New Jersey. Charles II also gave Jersey a special royal mace. This mace is still carried before the Bailiff at court and States meetings as a "perpetual remembrance of [the Bailiffs'] fidelity."

Another gift from Charles II was the "perquages." These were special routes that offered safety to people who had committed minor crimes and needed to leave the island. They could have nine days of safety in a parish church, then had to leave using a perquage route to the sea.

In 1666, there were worries that King Louis XIV of France planned to invade Jersey. The Governor gathered the militia, ready to defend the island. However, peace was agreed before any invasion happened.

In 1673, people were concerned about too many houses being built on farmland. This put the island's food supply at risk. So, the States declared that new houses should only be built in St Aubin and Gorey, or on large plots of land.

In 1680, the States voted to build Jersey's first dedicated prison in town, closer to the Royal Court. Before this, prisoners were held at Mont Orgueil. The new prison was finished by 1699.

William of Orange: Smuggling and Tensions

In 1689, William of Orange became King of England. England, as an ally of the Dutch, went to war against the French. During this time, Jersey lost its long-held "Privilege of Neutrality." William banned all trade with France, which included Jersey. However, due to corruption, especially from the Lieutenant-Governor Edward Harris, a large smuggling trade thrived. Smugglers would be signaled by fires set by French merchants on the Écréhous reef, part of Jersey. Jersey boats, with the Lieutenant-Governor's approval, would then go there for illegal trade.

During William's wars, Jersey was mostly peaceful, except in 1692. King Louis XIV had an army gather in France, and King James II also went there. However, the French fleet was destroyed in a naval battle in 1692. Although the threat from foreign powers was low, tensions were high on the island. The Governors and Bailiffs were often absent. The last de Carteret seigneur died, ending the male line of that powerful family.

Towards the end of the 1600s, Jersey's links with the Americas grew stronger. Many islanders moved to New England and Canada. Jersey merchants built successful businesses in the Newfoundland and Gaspé fisheries.

The 1700s: Unrest and Battles

Public Unrest and the Corn Riots

By the 1720s, differences in coin values between Jersey and France caused economic problems. The States of Jersey decided to reduce the value of the local coin, the liard. This led to popular riots in 1729, which forced the change to be cancelled.

In the 1730s, there was some violence against those collecting Crown taxes, especially in St Ouen, St Brelade, and Trinity.

A major revolt, known as the Corn Riots or the Jersey Revolution, happened in 1769. These riots were about the balance of power between the island's parliament, the States, and the Royal Court. Both had the power to make laws. There was also strong opposition to the feudal economic system. The riots started because of a corn shortage, partly caused by corruption among the ruling class.

On September 28, 1769, men from the northern parishes marched into town and rioted. They even broke into the Royal Court. The States retreated to Elizabeth Castle and asked the Privy Council for help. The Council sent five companies of soldiers, who then learned about the islanders' complaints.

The protesters demanded lower wheat prices and the end of some or all feudal privileges. In response, the Crown issued the Code of 1771. This code tried to separate the island's judiciary (courts) and legislature (law-making body). It wrote down Jersey's laws and took away the Royal Court's power to make laws. While the feudal system wasn't completely abolished, stricter rules were put on collecting Crown revenues.

Politics and Religion in the 1700s

The Chamber of Commerce, founded on February 24, 1768, is the oldest English-speaking Chamber of Commerce.

The late 1700s saw the first political parties appear on the island. Jean Dumaresq was an early Liberal who wanted democratic reforms. He believed the States should be made of democratically elected Deputies and have executive power. His supporters were called Magots ("maggots"), a name their opponents first used as an insult, but which the Magots adopted. His opponents were called Charlots.

Methodism arrived in Jersey in 1774, brought by fishermen returning from Newfoundland. Conflicts arose when men refused to attend militia drills that conflicted with chapel meetings. The Royal Court tried to ban Methodist meetings, but King George III refused to allow such interference with religious freedom. The first Methodist minister was appointed in Jersey in 1783. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached in Jersey in August 1789. His words were translated into the local language for those from the country parishes.

The Battle of Jersey

The 1700s were a time of tension between Britain and France as their global ambitions clashed. Because of its location, Jersey was almost constantly ready for war.

During the American Wars of Independence, there were two attempts to invade the island. In 1779, the Prince of Orange was stopped from landing at St Ouen's Bay. On January 6, 1781, a French force led by Baron de Rullecourt captured St Helier in a surprise early morning attack. However, they were defeated by a British army led by Major Francis Peirson in the Battle of Jersey.

After a brief peace, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars followed. These wars changed Jersey forever. In 1799–1800, over 6,000 Russian troops were stationed in Jersey after being evacuated from Holland.

After the Battle: Trade and Reform Demands

The end of the war with France and America led to more trade between Jersey and the New World, especially Canada and Newfoundland. By 1763, about a third of the fish exported from Conception Bay was carried by Jersey ships. In the 1780s, some Jersey families settled permanently in places like Forteau, Labrador. The first printing press was brought to Jersey in 1784.

Anti-seigneurial feelings remained strong in Jersey, even after the reforms of 1771. In 1785, a document with 36 articles against the feudal system was included in St Ouen's Parish Assembly minutes. It demanded reforms like ending Seigneurial services and stopping the seizure of goods after bankruptcy. These demands were also made in St Helier and St John. They formed the basis for a long struggle against the feudal system in the next century.

The 1800s: Big Changes in Society

The 1800s brought huge changes to Jersey. Many immigrants from England arrived, making Jersey more connected than ever. This led to cultural changes and a desire for political reform. During this time, the States became more representative of the population. Jersey's culture became more English and less religious. The island's economy also grew, and built-up areas, especially St Helier, expanded. Public transport also developed.

Before Queen Victoria: Roads and Harbours

Jersey's old road network was a complex maze of narrow lanes. In the early 1800s, the governor, General George Don, built new military roads. These roads connected coastal forts to the town harbour. He sometimes had to build them at gunpoint because landowners opposed them. Islanders thought the old, winding lanes were the best defense. The new roads were expensive and met with much opposition. However, they allowed faster communication across the island. Once peace returned, these roads helped farmers quickly transport crops to waiting ships. This connected Jersey's agriculture to markets in London and Paris.

After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the Channel Islands lost their strategic military importance. The cost of defending the islands was high, even in peacetime. Some questioned the value of having the islands. However, in 1845, the Duke of Wellington strongly defended the islands' importance to the UK.

A key change for Jersey was the introduction of steamships. Before this, travel to the island was long and unpredictable. In the mid-1820s, the post office started using steamships. The first paddle steamer visited Jersey in 1823. By 1824, two shipping companies offered weekly steamship services to England.

This brought thousands of passengers to Jersey. By 1840, there were 5,000 English residents. Many say they didn't mix much with the native Jerseymen. The growing number of English-speaking soldiers and retired officers led to St Helier gradually becoming an English-speaking town. This new immigration greatly influenced local architecture. Many Georgian-style houses were built. St Helier also expanded with new streets. In 1831, street lighting was first used. The rapid growth of St Helier was one of the biggest changes in Jersey's landscape during the 1800s.

An important development for St Helier was the construction of its harbour. Before, ships only had a small jetty. The Chamber of Commerce pushed for a new harbour. When the States refused, the Chamber paid to upgrade the harbour in 1790. A new breakwater was built. In 1814, merchants built roads to connect the harbours to the town. In 1832, the Esplanade and its sea wall were finished. The rapid growth in shipping led the States in 1837 to order the construction of two new piers: the Victoria and Albert Piers.

A New Island Politics: Reform and English Influence

The period after the Napoleonic Wars was politically divisive for Jersey. In 1821, an election for Jurat led to violence between the conservative Laurelites and the progressive Rose men.

At this time, Jersey's government still resembled a feudal system. It also had overlapping judicial and law-making powers. In the 1800s, the growth of St Helier shifted economic power from the country parishes to the town. St Helier also had a large English population. During this century, Jersey's power shifted from the English Crown to the Jersey States. This made Jersey almost an independent state. However, the ultimate authority over the island shifted from the Crown to the British Parliament.

The Privy Council pressured Jersey to reform its institutions to be more like the English system. Many locals blamed this push for reform on the island's new immigrants. These immigrants were not used to Jersey's unique political and legal systems. Many English people who moved to Jersey found an unfamiliar environment with laws they didn't understand and no easy way to influence local power.

Abraham Le Cras, a new resident with Jersey heritage, strongly opposed Jersey's self-government. He believed Jersey should be fully integrated into England. In 1840, he won a court case challenging the States' ability to make people citizens. The Privy Council ruled that the States' long-standing practice was no longer valid. In 1846, he convinced a Member of Parliament to push for a committee to investigate Jersey's law. Instead, the British Government promised a Royal Commission. The Commission suggested replacing the Royal Court, run by Jurats, with three Crown-appointed judges and a paid police force. Le Cras moved to England in 1850.

In 1852, Jersey faced a constitutional crisis. The Privy Council issued three orders: creating a police court, a petty debts court, and a paid police force for St Helier. This caused controversy, with claims that it threatened Jersey's independence. Both political parties united against the move, and about 7,000 islanders signed a petition. By 1854, the council agreed to cancel the orders, if the States passed most of the council's requirements. In 1856, further reforms brought Deputies into the States for the first time. Each country parish got one Deputy, and St Helier got three.

Threats to Jersey's self-rule continued. In the 1860s, there was a threat that the British Parliament itself might intervene to change the island's government.

Anglicisation: Becoming More English

At the start of the 1800s, Jersey people saw themselves as British, not French or Norman. As more French immigrants arrived, the differences between islanders and French people became clearer. France and the French were seen as foreign. Also, increased links between Jersey and mainland Britain, like better shipping and more British immigrants, made Jersey more British.

This led to a change in the island's language. In the early 1800s, St Helier became mostly English-speaking, though many people were bilingual. This created a language divide. People in the countryside continued to use Jèrriais, and many didn't even know English. English became seen as "the language of commercial success and moral and intellectual achievement."

The growth of English and the decline of French led to Jersey adopting more values and social structures from Victorian England. From 1912, new compulsory education was taught only in English. This followed English cultural norms and taught subjects from an English perspective. This eventually led to the island's culture becoming anglicised. Much of the traditional Norman-based culture was ignored or lost. Some believe this cultural change made native Jersey culture and language feel inferior.

The British state supported anglicisation. It was thought that this would encourage loyalty and friendship between the nations. It was also believed to bring economic success and "general happiness." In 1846, there was concern about sending young islanders to France for education. They might bring French ideas and friendships back to the British Islands. The Jersey gentry (upper class) supported anglicisation because of the social and economic benefits it would bring. In 1856, the Jersey Times, an English-language newspaper, was started. The use of English in debates in the States was first suggested in 1880.

Victorian Era: Queen Victoria and Modernization

Queen Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom and Jersey in 1837. The first major event for Jersey in the Victorian era was a change in currency. For centuries, the French livre tournois had been used. However, it was abolished during the French Revolution. Although the coins were no longer made, they remained legal in Jersey until 1837. Then, due to dwindling supplies, Jersey adopted the pound sterling as its official money. To avoid another riot like the Six-sou Revolt, authorities made sure there was a fair exchange rate. Jersey issued its first coins in 1841.

In the 1840s, the Rose leader Pierre Le Sueur was elected as Constable of St Helier. From 1845, he organized the building of a complete sewer system for the town. He stayed in office for 15 years. After his death, a monument was built in his honor.

Jersey's population grew quickly, from 47,544 in 1841 to 56,078 twenty years later. Both immigration and emigration increased. In 1851, about 12,000 English immigrants lived in Jersey. In St Helier, they made up 7,000 of the parish's 30,000 residents. The English community in Jersey was divided by social class. Wealthy people retired to the island and created their own English social life. Working-class English immigrants often lacked basic rights.

In 1852, the famous French author Victor Hugo came to Jersey for safety. Many other revolutionaries and socialists from Europe also found refuge here. In 1855, some of these refugees published an open letter in their newspaper that criticized Queen Victoria. The Lieutenant-Governor banished the three editors. Although Hugo disagreed with the letter, he protested the expulsion and was also exiled from the island. He and his family then moved to Guernsey.

The Theatre Royal was built, as was Victoria College in 1852. Jersey exhibited 34 items at The Great Exhibition in 1851. The world's first ever Pillar box (post box) was installed in 1852. A paid police force was created in 1854.

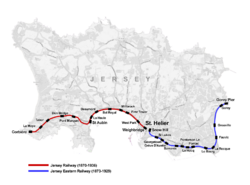

This century saw Jersey develop a public transport network. Omnibuses (horse-drawn buses) started to be used. Two railways were opened: the Jersey Western Railway in 1870 and the Jersey Eastern Railway in 1874. The western railway went from St Helier to La Corbière. The eastern railway went from St Helier to Gorey Pier. The two railways were never connected.

Jersey was the fourth-largest shipbuilding area in the 1800s in the British Isles. It built over 900 ships. Shipbuilding declined with the arrival of iron ships and steam. Several banks in Jersey failed in 1873 and 1886. The population slightly decreased in the twenty years leading up to 1881.

In the late 1800s, as the old cider and wool industries declined, Jersey farmers benefited from two new luxury products: Jersey cattle and Jersey Royal potatoes. Jersey cattle were developed through careful breeding. The Jersey Royal potato was a lucky accident.

The anarchist philosopher, Peter Kropotkin, visited the Channel Islands in 1890, 1896, and 1903. He described Jersey's agriculture in his book The Conquest of Bread.

The 1800s also saw the rise of tourism as an important industry. This was linked to better passenger ships. Tourism reached its peak after the Second World War until the 1980s.

The 1900s: Wars, Reforms, and Finance

Basic education became required in 1899 and free in 1907. Queen Victoria died in 1901, and Edward VII was proclaimed King in the Royal Square. His coronation a year later was celebrated with the first Jersey Battle of Flowers. Before the First World War, the Jersey Eisteddfod (a cultural festival) was founded. The first airplanes arrived in Jersey in 1912.

In 1914, the British military garrison was withdrawn at the start of the First World War. The militia was called into action. Jersey men served in both the British and French armed forces. German prisoners of war were held in Jersey. The influenza epidemic of 1918 added to the war's toll.

In 1919, imperial measurements largely replaced Jersey's traditional weights and measures. Women over 30 were given the right to vote. The funds from old grammar schools were repurposed for scholarships to Victoria College.

In 1921, King George V visited, which led to the design of the parish crests.

In 1923, the British government asked Jersey to contribute money each year to the costs of the Empire. The States of Jersey refused. Instead, they offered a one-time contribution to war costs. After talks, Jersey's one-off payment was accepted.

The first motor car arrived in 1899. Buses started running on the island in the 1920s. By the 1930s, competition from motor buses made the railways unprofitable. They finally closed in 1935 after a fire. Jersey Airport opened in 1937. Before this, planes used St Aubin's Bay beach as an airstrip at low tide.

English was first allowed in debates in the States of Jersey in 1901. The first law written mainly in English was the Income Tax Law of 1928.

German Occupation (1940–1945)

After the British government withdrew its defenses and the Germans bombed the island, Jersey was occupied by German troops between 1940 and 1945. The Channel Islands were the only British land occupied by German troops in World War II. During this time, about 8,000 islanders were evacuated. 1,200 islanders were sent to camps in Germany. Over 300 islanders were sentenced to prison and concentration camps in Europe. Twenty of them died. Islanders faced near-starvation in the winter of 1944–45. They were cut off from German-occupied Europe by Allied forces. Help arrived with the Red Cross supply ship Vega in December 1944. Liberation Day on May 9 is a public holiday.

After Liberation: Rebuilding and Modernization

After five years of occupation, the people of Jersey began to rebuild the island. In 1944, a group of exiled islanders, called Nos Iles, planned what the Channel Islands would need after the war. This included better education, economic development (especially tourism), and more cooperation between the islands. They also stressed the need for good land management.

The UK donated over £4 million to help Jersey clear its occupation debt. They also sent gifts of essential items. Over 50,000 mines had to be cleared.

The 1945 census showed 44,382 people living on the island. By the next year, there were 50,749, with most living in St Helier. Many returned to damaged homes and received grants to repair them.

Many islanders called for reforms and modernization of the States. A poll showed that most people wanted Rectors out of the States and the legislature and judiciary separated. The Jersey Democratic Movement wanted the island to become a county of England or at least abolish the States. The Progressive Party, made up of some States members, opposed the JDM. In the 1945 Deputies' election, the Progressives won by a large margin, giving them a clear demand for change.

Voting rights were extended to all British adults. Before, only men and women over 30 who owned property could vote. The biggest reform came in 1948. Jurats were no longer members of the States. They would be elected by a special Electoral College. A retirement age of 70 was set for Jurats. The Bailiff became the judge of the law, and the Jurats the "judge of fact." The Jurats' role in the States was replaced by 12 Senators. The Church also lost most of its representation. The number of Deputies increased to 28.

The island adopted free, universal secondary education and a social security system. Divorce was made legal in 1949. In 1952, a state secondary school for boys opened, and one for girls opened. Later, these combined to form a single co-ed grammar school. Two other comprehensive schools were opened at Les Quennevais and Le Rocquier. Highlands College was bought by the States in 1973 for further education.

Housing expanded to deal with the growing population and improve existing homes. There was also a program to clear slums. By 1948, two new housing estates had been built.

The population grew with wealthy immigrants seeking lower taxes and seasonal workers from Europe and mainland Britain. Jersey was especially attractive to retired civil servants from former British colonies as they gained independence. This created a need for new infrastructure. Street lighting spread to country parishes. A new sewage plant was built. Mains drainage extended beyond St Helier, and new water production facilities were built. Tourism grew, and the Battle of Flowers parade reopened. New cinemas and the International Road Race also started.

The British Government handed over the island's military bases to Jersey. Jersey's Militia was abolished. For the first time since Edward III, there was no permanent military presence on the island. Arsenals, forts, and castles were turned into museums and housing. Fort Regent became the main leisure center for St Helier. There was a dispute between the UK and France over the ownership of Jersey's small islands, the Minquiers and the Écréhous. The International Court of Justice ruled in favor of British ownership.

Between 1945 and the Queen's coronation in 1952, there were outbreaks of polio and tuberculosis. The Jersey Maternity hospital and St John Ambulance headquarters opened. Agriculture was affected by several foot-and-mouth outbreaks.

In the first senatorial election, Philip Le Feuvre topped the poll. On December 8, 1945, Ivy Forster of the Progressive Party became the first woman ever elected to the States.

The most significant change in modern Jersey has been the growth of the finance industry from the 1960s onwards. This has led to discussions about whether Jersey is a tax haven. Jersey's role as a finance center has sometimes brought it global media attention. For example, in 2017, the Paradise Papers, a leak of secret documents, showed that Apple had made two international companies tax resident in Jersey in 2015.

See also

Other Histories of the Channel Islands

- German occupation of the Channel Islands

- Archaeology of the Channel Islands

- Maritime history of the Channel Islands

- List of English monarchs

- List of British monarchs

Related articles for Jersey

- Lieutenant Governor of Jersey

- Culture of Jersey

- Politics of Jersey

- Demographics of Jersey (contains historical figures)

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |