History of Norfolk, Virginia facts for kids

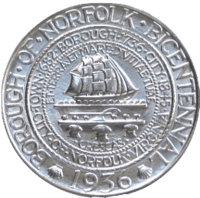

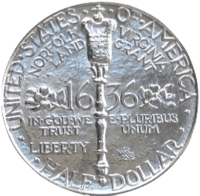

The history of Norfolk, Virginia began as a modern town in 1636. It officially became a city in 1736. During the American Revolutionary War in 1776, the city was burned. This happened on orders from the last British governor, Lord Dunmore. However, Norfolk was quickly rebuilt.

The 1800s were tough for Norfolk. Wars, diseases, fires, and money problems slowed its growth. Despite this, the city became a major economic center. By the late 1800s, the Norfolk and Western Railway helped make Norfolk a huge port for exporting coal. It also became a hub for many other railroads. These connected its ports to inland parts of Virginia and North Carolina. By the early 1900s, coal from the Appalachia region was easily shipped from Norfolk. Farmers in nearby counties became leaders in growing vegetables. They produced over half of all greens and potatoes eaten on the East Coast. Lynnhaven oysters also became a big export.

After the American Civil War (1861–1865), African Americans in the region gained their freedom. President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation (1862–1863) and later constitutional changes helped. However, they soon faced harsh rules called Jim Crow Laws. These laws were put in place by white lawmakers in the 1890s. After Virginia passed a new state constitution, African Americans lost their right to vote for over 60 years. They finally regained these rights through their leaders' efforts and new federal laws in the 1960s.

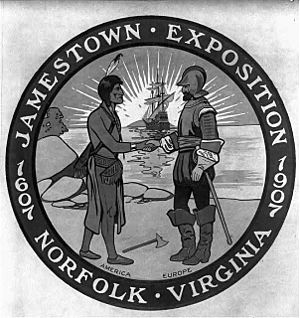

In 1907, Norfolk hosted the Jamestown Exposition. This event celebrated 300 years since the first English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. It was the only world's fair ever held in Virginia. Because of this event, and visits from important people, Norfolk later became home to the Norfolk Naval Station. Today, Norfolk is a major U.S. naval and shipping center. It is also the main city of the Hampton Roads area.

Contents

Early People and Settlements

The first signs of humans in Virginia date back to 9,500 BC.

Native American Life

In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh sent explorers to find a good place for an English settlement. They landed on Roanoke Island (now in Dare County). One of Raleigh's commanders, Arthur Barlowe, wrote in his journal that the area had a Native American tribe called the Chesepian. Barlowe said the Chesepians had a great city nearby called Skicoak. However, its exact location is still unknown.

When settlers arrived at Cape Henry in 1607, they found no trace of Skicoak. According to a book from 1612, the Chesepians had been wiped out. This was done by Chief Powhatan, the leader of the Powhatan Confederacy.

Colonial Norfolk (1607-1775)

In 1607, Virginia Colony Governor Sir George Yeardley created four "citties" (cities). These cities helped govern the colony and formed the House of Burgesses. The southeastern part of the Hampton Roads area was part of Elizabeth Cittie. In 1622, Adam Thoroughgood (1604–1640) from Norfolk, England, became one of the first English settlers in this area. He came as an indentured servant, meaning he worked for a period to pay for his trip. After his service, he became a respected citizen.

In 1624, the Virginia Company went bankrupt, and Virginia became a royal colony, controlled by the King. Around this time, King James I gave 500 acres (2 km²) of land to Thomas Willoughby. This land is now the Ocean View section of Norfolk. The whole Virginia colony had about 5,000 people then.

Growth and County Divisions

In 1629, Thoroughgood was elected to the House of Burgesses. In 1634, the King divided the colony into 8 shires. Much of Hampton Roads became part of Elizabeth City Shire. In 1636, Thoroughgood received a large land grant for bringing 105 people to the colony. He is also believed to have suggested the name Norfolk, after his birthplace. New Norfolk County was created from Elizabeth City Shire that same year. The King also gave 200 more acres (0.8 km²) to Willoughby, which would later become the city of Norfolk. In 1637, New Norfolk County split into Upper Norfolk County and Lower Norfolk County. Modern Norfolk is in Lower Norfolk.

In 1649, William and Susannah Moseley from England moved to Lower Norfolk County. They built a manor house called Rolleston Hall near the Eastern Branch Elizabeth River. It stood for over 200 years before burning down.

Norfolk Becomes a Port City

In 1670, a royal order called for "storehouses to receive imported merchandise ... and tobacco for export" in each county. This made Norfolk important as a port city, thanks to its natural deepwater channels. Around 1673, the "Half Moone" fort was built where Town Pointe Park is today. This fort was built because of fears of a Dutch attack, but it never happened.

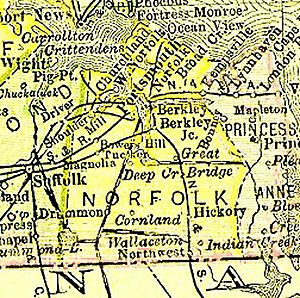

Norfolk grew quickly. By 1682, it received a special charter to become the "Towne of Lower Norfolk County." Norfolk was one of only three cities in Virginia to get a royal charter, the others being Jamestown and Williamsburg. The town started at the meeting point of the Eastern and Southern Branches of the Elizabeth River. In 1691, Lower Norfolk County split again, forming Norfolk County (today's Norfolk, Chesapeake, and parts of Portsmouth) and Princess Anne County (today's Virginia Beach). Norfolk officially became a city in 1705 and a borough in 1736.

In 1753, Lt. Governor Robert Dinwiddie gave the growing city a silver mace. This mace was 41 inches (104 cm) long and weighed 104 ounces. It was a symbol of royal power and is now at the Chrysler Museum of Art.

By 1775, Norfolk was one of Virginia's richest cities. It was a major shipbuilding center. It was also a key place for shipping goods like tobacco, corn, cotton, and timber from Virginia and North Carolina to Britain. In return, goods like rum and sugar from the West Indies, and finished products from England, came through Norfolk. Many of these products were made by enslaved people.

Revolutionary War (1775 - 1783)

Norfolk had many people who supported the British during the American Revolution. In summer 1775, Lord Dunmore, Virginia's last Royal Governor, tried to regain control from Norfolk. In November, a battle at Kemp's Landing was a clear win for Dunmore. But it was clear the war was getting bigger. The governor then issued Dunmore's Proclamation. This promised freedom to any enslaved person who joined the British forces.

By late November, Dunmore set up a strong base in Norfolk. He tore down about 30 houses to build it. A few days later, Dunmore's 600 soldiers were defeated at the Battle of Great Bridge. 102 of his soldiers were killed or hurt, while only one patriot was injured. Dunmore and his supporters left Norfolk and boarded their ships. This ended 168 years of British rule in Virginia.

Dunmore stayed in the river near Norfolk with his ships. On New Year's Day 1776, his ships began firing on the city. This led to the Burning of Norfolk. British troops also went ashore to burn waterfront buildings. This played into the hands of the rebels. The rebels were happy to see a city with many British supporters destroyed. They were even happier to blame it on the British. Over the next two days, they helped the fires spread and looted houses. The Virginia Assembly found that out of 882 houses burned, only 19 were set by the British. Another 416 houses were destroyed in February 1776. This was to stop the British from using them if they returned. Only Saint Paul's Episcopal Church survived the attack and fires. However, a cannonball from the Liverpool dented the church.

Rebuilding and Challenges (1783-1861)

Four years after the Revolutionary War, a fire destroyed about 300 buildings along Norfolk's waterfront. This caused a big economic problem for the city. Around 1800, the U.S. government built Fort Norfolk to protect the harbor.

In the 1820s, farming communities in South Hampton Roads faced a long economic downturn. Many families moved to other parts of the South. From 1820 to 1830, Norfolk County lost about 15,000 people.

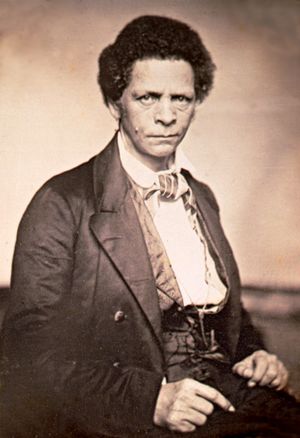

Like other Southern states, Virginia struggled with slavery. It became less important as farming changed from tobacco to other crops. Virginia thought about ending slavery by law or sending Black people to Africa to start a colony in Liberia. The American Colonization Society (ACS), started in 1816, was the biggest group for this. Many people from Virginia and North Carolina sailed to Africa from Norfolk. One was Joseph Jenkins Roberts, born in Norfolk, who became the first president of Liberia. This movement ended after the American Civil War.

By 1840, Norfolk had 10,920 people. With more people, there was more interest in education and culture. In 1841, a new school building for Norfolk Academy was finished. It was designed to look like a Greek temple. In 1845, Norfolk officially became a city. By 1850, the city had about 14,000 people. This included 4,000 enslaved African Americans and 1,000 free Black people.

Better transportation helped Norfolk grow. In 1832, the steam ferry Gosport started connecting Norfolk and Portsmouth. In 1851, a new railroad was approved to connect Norfolk with Petersburg. This 80-mile (129 km) line was finished in 1858. It was the start of today's Norfolk Southern Railway.

Yellow Fever Epidemic

On June 7, 1855, the ship Benjamin Franklin stopped in Portsmouth for repairs. A health officer checked the ship and suspected problems, even though the captain said it was fine. The officer ordered the ship to stay in the harbor for 11 days. Later, he let it dock, but said its cargo hold should not be opened. Within days, the first cases of Yellow Fever appeared near the wharf. By July, the disease was widespread. It killed over 3,000 people in the region, with 2,000 in Norfolk alone. At its worst, over 100 people died each day in Norfolk. The city's population did not recover until after the American Civil War. In 1856, the Sisters of Charity started St. Vincent's Hospital partly because of this epidemic.

American Civil War

In early 1861, Norfolk voters chose to leave the Union. Soon after, Virginia voted to secede and join the Confederacy. Richmond became the Confederate capital, and the American Civil War began.

When Virginia joined the Confederacy, they demanded all federal property. This included the Norfolk Navy Yard (then called the Gosport Shipyard). A Confederate trick led Union commander Charles Stewart McCauley to burn the shipyard. He then moved his staff to Fort Monroe across Hampton Roads. The Confederates captured the shipyard. They got a lot of war supplies, including the remains of the burned ship USS Merrimac.

In spring 1862, the USS Merrimac was rebuilt at Norfolk Navy Yard. It was made into an ironclad ship and renamed the CSS Virginia. The Battle of Hampton Roads started on March 8. The battle ended in a tie. Neither ironclad could seriously damage the other due to their heavy armor. For months, the CSS Virginia tried to fight the Monitor, but the USS Monitor was ordered not to fight unless absolutely needed.

On May 6, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln visited Fort Monroe. He saw how important Norfolk was. He decided to capture the city to remove the CSS Virginias base. On May 8, Union ships and Fort Wool batteries fired on Confederate batteries at Sewell's Point. The CSS Virginias approach forced Union ships back to Fort Monroe. Lincoln then ordered an invasion of Willoughby Spit for the next day. On May 10, General John Wool landed 6,000 Union soldiers there. Within hours, Union troops reached Norfolk. Mayor William Lamb surrendered the city without a fight.

Norfolk was under Martial law for the rest of the Civil War. Many private and public buildings were taken for federal use. Mayor Lamb managed to hide the city's silver mace under a fireplace. This kept Union troops from taking or melting it.

Enslaved African Americans did not wait for the war to end to be free. When Union troops arrived, thousands escaped to Norfolk and Fort Monroe. They claimed their freedom. Even before northern missionaries arrived, African Americans started schools for children and adults.

Reconstruction to the Jamestown Exposition (1865-1907)

By 1870, the Reconstruction era was ending in Norfolk. Union troops left, and Virginia rejoined the Union. During this time, African Americans in Hampton Roads were elected to state and local offices. However, white violence and unfair laws slowly removed them from office and voting. These included Jim Crow Laws, which controlled work, separated public places, and transportation.

In 1902, Virginia created a new constitution. This constitution stopped almost all African Americans from voting. It used new rules for voter registration that were used unfairly against them. White leaders achieved their goal: from 1900 to 1904, almost no Black people voted in Virginia's Presidential elections.

African Americans did not get their full voting and civil rights back until the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-1960s. Despite these harsh limits, many African Americans built strong families, churches, schools, and community groups. Many became landowners and farmed small plots in the Norfolk area.

In 1883, the first train car of bituminous coal arrived from the Pocahontas fields via the Norfolk & Western Railway. By 1886, tracks reached the coal piers at Lambert's Point. This made Norfolk one of the world's largest coal shipping ports. In 1894, classes began at the city's first public high school. That same year, electric street railways came to Norfolk. Within ten years, they connected Norfolk to nearby communities like Sewell's Point, Ocean View, and Portsmouth.

1907 brought both the Virginian Railway and the Jamestown Exposition to Sewell's Point. A large Naval Review at the Exposition showed how good the area was for a naval base. This led to the world's largest naval base being built there. The Exposition celebrated 300 years since Jamestown was founded. Many important people attended, including President Theodore Roosevelt, politicians, and diplomats from 21 countries. Many naval ships from different countries were there. The area of the exposition became Naval Air Station Hampton Roads, later Naval Station Norfolk, in 1917 during World War I.

Beach Resorts and Travel

After the Civil War, resort areas grew along the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean. Norfolk residents enjoyed day trips to the beaches. Ocean View in Norfolk County was planned before the war. But a 9-mile (14 km) narrow gauge steam train service between downtown Norfolk and Ocean View brought many people. It was first called the Ocean View Railroad. A small steam train named the General William B. Mahone carried more and more passengers, especially on weekends. Similarly, the Norfolk & Virginia Beach Railway started train service in 1883 to Seatack on the Atlantic Ocean. The oceanfront area at Seatack became the site of the area's first resort hotel.

As more people visited, the steam trains to Ocean View and Seatack were replaced by electric trolley cars. Later, these were replaced by highways and cars. Cottage Toll Road, later Tidewater Drive, led to Ocean View. Leading from Norfolk to Seatack, which became known as Virginia Beach, the new Virginia Beach Boulevard in 1922 greatly helped the growth of the oceanfront town.

Ocean View slowly became a streetcar suburb. Norfolk officially took it over in 1923. Virginia Beach became a town in 1906 and an independent city in 1952. In 1963, the city of Virginia Beach joined with Princess Anne County. This created the modern City of Virginia Beach, Norfolk's neighbor to the east. This was part of a trend of cities and counties joining together in Hampton Roads between 1952 and 1976.

Modern Norfolk

City Growth (1906-1959)

Norfolk continued to grow in the first half of the 1900s by adding nearby areas. In 1906, the town of Berkley was added. This stretched the city limits across the Elizabeth River. Berkley became a borough, like Beacon Light and Hardy Field. Lambert's Point, with its railroad pier, and Huntersville were added to Norfolk five years later in 1911.

In 1923, the city limits grew to include Sewell's Point, Willoughby Spit, Campostella, and Ocean View. This added the naval base and miles of beach along Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. The Norfolk Naval Base grew fast because of World War I, causing a housing shortage. These new areas grew quickly, along with the Larchmont neighborhood. Wards Corner, then just outside Norfolk, became the first shopping area outside of downtown in the country.

In 1930, Old Dominion University started as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary. ODU gave its first bachelor's degrees in 1956 and became an independent university in 1962. Five years later, Norfolk State University was founded and became independent in 1969.

By 1950, Norfolk was the fifth fastest-growing city area in the U.S. After World War II, there was another housing shortage. In 1955, Tanners Creek was added. Norfolk became the largest city in Virginia, with 297,253 people. After a smaller addition in 1959 and a land swap with Virginia Beach in 1988, the city reached its current size.

New Roads and Tunnels

With the start of the Interstate Highway System, new roads opened. Over fifteen years, a series of bridges and tunnels connected Norfolk to the Peninsula, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach.

On November 1, 1957, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel opened. It connected the Virginia Peninsula with Norfolk, as State Route 168. This new two-lane toll bridge-tunnel became part of Interstate 64 by late 1957. A second tunnel was built in 1976, making it four lanes. The two-lane Midtown Tunnel was finished on September 6, 1962. On December 1, 1967, the Virginia Beach-Norfolk Expressway (Interstate 264 and State Route 44) opened. This 12.1-mile (19.5 km) toll road cost $34 million.

In 1991, the new Downtown Tunnel/Berkley Bridge was completed. It included new highway lanes and interchanges. These connected Downtown Norfolk and Interstate 464 with the Downtown Tunnel.

School Desegregation (1958 - 1960)

In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision said that separating races in public schools was against the law. However, Virginia tried to avoid this. This policy was called Massive Resistance. New state laws, called the Stanley plan, stopped state money for integrated schools.

Norfolk's private schools had already integrated four years earlier. But many public school divisions (school districts) were afraid to integrate because they might lose state money. In 1958, federal courts ordered schools in Arlington County, Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Warren County to integrate. That fall, a few public schools in these areas opened with students of different races for the first time. In response, Virginia Governor J. Lindsay Almond Jr. ordered the schools closed. This included six Norfolk Public Schools: Granby High, Maury High, Norview High, Blair Junior High, Northside Junior High, and Norview Junior High.

In Norfolk, this meant 10,000 children were locked out of school. This caused a huge public outcry. Some children went to makeshift schools in churches. Citizens voted on whether to reopen the public schools. The ballot made it clear that Virginia would stop funding integrated schools.

On January 19, 1959, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals said the state law went against Virginia's own constitution. The court ordered all public schools to be funded, whether integrated or not. Governor Almond gave in about ten days later. He asked the General Assembly to cancel several "Massive Resistance" laws. On February 2, 1959, Norfolk's public schools were desegregated. 17 Black children entered six schools that were previously only for white students. The Virginian-Pilot newspaper editor Lenoir Chambers wrote against "Massive Resistance" and won a Pulitzer Prize.

Downtown Changes (1960 onward)

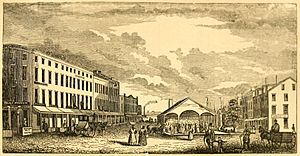

Norfolk's downtown waterfront was historically busy with shipping and port activities. But with new containerized shipping in the mid-1900s, the old port facilities became outdated. Larger, more modern ports opened elsewhere in the region. In the second half of the century, Norfolk's downtown shopping area, Granby Street, also struggled. New suburban shopping centers offered more convenience. These included Pembroke Mall in Virginia Beach and JANAF Shopping Center in Norfolk.

Starting in the 1970s, Norfolk worked to bring its downtown back to life:

Granby Street Mall

To compete with suburban malls, Norfolk leaders tried to create a similar mall experience on Granby Street. They called it the "Granby Street Mall" and closed the street to cars. But this pedestrian mall did not succeed and faced problems in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Waterfront Renewal

Another focus was the waterfront, with its old piers and warehouses. Norfolk used federal money to tear down many old buildings downtown. This included poor housing that lacked indoor plumbing. The old City Market, Norfolk Terminal Station (the train station), and The Monticello Hotel were also torn down.

Near the water, almost all the old shipping buildings were removed. They were replaced with a new road, Waterside Drive. New buildings included the Waterside Festival Marketplace, a mall like Baltimore's Inner Harbor Pavilions. Also built were Town Point Park, a park with wide river views, and the Norfolk Omni Hotel.

On the other side of Waterside Drive, the old warehouses made way for tall buildings.

MacArthur Center

In the mid-1990s, Norfolk tried again to improve Granby Street. In late 1996, a new downtown shopping mall was announced. It would include a Nordstrom store. The mall was named the MacArthur Center, after the World War II General whose tomb was across the street. Nearly $100 million in public money was used for roads, parking garages, and other improvements for the mall. The MacArthur Center opened in March 1999. It is a three-story enclosed mall with an 18-screen movie theater.

More Downtown Growth

The number of people living downtown keeps growing. Old commercial buildings are being turned into homes, and new residential buildings are being built.