History of Roman-era Tunisia facts for kids

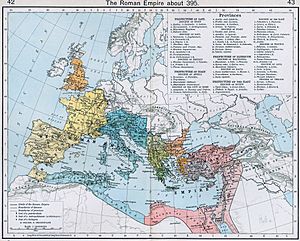

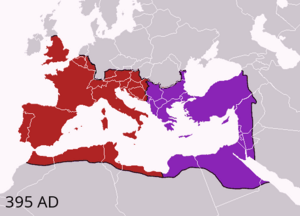

Long ago, the land we now call Tunisia was part of the ancient Roman Empire. It started as a Roman province named Africa. As the Roman Empire grew, more of Tunisia became part of another province called Africa Nova.

The powerful Carthaginian Empire was finally defeated by the Romans in the Third Punic War (149–146 BC). After this, some nearby kingdoms ruled by Berber kings became friends with Rome. Eventually, these lands were taken over by Rome and reorganized. The city of Carthage was rebuilt and became a very important capital, one of the biggest cities in the Roman Empire.

This led to a long time of peace and wealth. The region became rich from farming and exporting crops. This also created a diverse culture with people from many places.

Christianity became very important in this Roman province. It even gave the Roman Catholic Church three Popes and famous thinkers like Augustine of Hippo.

Later, a group called the Vandals invaded Tunisia in 439 AD. They ruled the province for almost 100 years. During this time, several Berber groups fought back, and some even created their own independent areas.

The Byzantine Empire eventually took the area back from the Vandals in 534 AD. They ruled until the Islamic conquest in 705 AD.

Contents

Roman Africa: A New Province

After Carthage lost the Third Punic War (149–146 BC), the Roman Republic destroyed the city. Rome then took control of the rich farmlands around it. At first, the old city of Utica, located north of ruined Carthage, became the capital of this new Roman province.

The Roman province was named Africa after the local Berber people. The Romans called these people Afri. Later, the Arabic name for the region, Ifriqiya, came from this Roman name.

Lands next to the Roman province were given to Rome's Berber allies. These allies continued to rule their own independent Berber kingdoms. Over time, Roman Africa grew to include all of modern Tunisia and much of northern Africa.

Carthage: A Rebuilt City

The rebuilding of Carthage began under Julius Caesar around 49 BC and continued with Augustus. After Utica lost its special status, Carthage became the capital of the new province called Africa Proconsularis around 27 BC. A Roman governor, called a proconsul, lived there.

Carthage became very successful during the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd centuries AD.

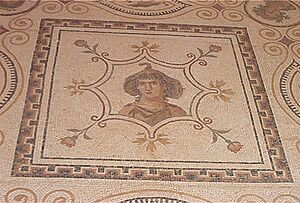

The province was famous for its beautiful mosaics. These were made by local artists and often showed detailed pictures. Many large mosaics covered the floors of courtyards and rooms in grand villas in Carthage and the countryside. Beyond Carthage, many older Punic and Berber towns also became strong and wealthy. New settlements were built, especially in the fertile Medjerda river valley, north and northwest of Carthage. A long Roman aqueduct, about 120 kilometers long, was built by Emperor Hadrian (who ruled from 117–138 AD). It brought water from a mountain sanctuary to ancient Carthage. This aqueduct was even repaired and used again in later centuries.

Carthage and other Roman cities in Africa had large buildings for public shows. These included exciting games with gladiators who fought wild animals or each other. One group of gladiators was called the Telegenii. Even if they came from humble backgrounds, a successful gladiator could become very popular.

Another popular city entertainment was the theater. Famous Greek tragedies and comedies were performed, along with Roman plays. Short, funny shows by mimes were also popular. More expensive shows featured pantomimes, where actors told stories through dance and gestures. The African writer Apuleius (around 125 – 185 AD) described how impressive these shows were. An old epitaph (a tomb inscription) celebrates a popular pantomime named Vincentius, saying he was "just, good and in his every relationship with each person irreproachable and sure."

Carthage and the province of Africa enjoyed peace and wealth. Over time, Roman security forces started to include local people. The Romans governed well, and the province became a strong part of the Empire's economy and culture. Many people moved there. Its diverse population was known for a high standard of living. Carthage became one of the top cities in the Empire, after only Alexandria and Rome.

Farming and Food Production

When Rome took over Carthage's lands in 146 BC, they wanted to control the rich harvests. Many Punic people who owned olive groves, vineyards, and farms had "fled into the hinterland."

Public lands became Rome's property. Many private lands were also taken if they were ruined, abandoned, or had unpaid taxes. Some good farming land, which had only been used seasonally by Berber herders, was also taken and given out for planting. This meant many nomads and small farmers became very poor or were forced into drier areas. Tacfarinas led a long Berber uprising (17–24 AD) against Rome, but his forces were eventually defeated. After this, farming grew and produced more crops. However, Rome "never succeeded in keeping the nomads of the south and west permanently in check."

Large farms, called latifundia, were created by investors or powerful people. These farms were rented out to coloni, often from Italy. These farmers settled around the owner's main house, forming small farming towns. The land was divided into squares. Many small farms were also owned by Roman citizens or army veterans, as well as by the original Punic and Berber owners. The many large and comfortable villas found in Africa Province from this time show how much wealth farming created.

Rich farmlands brought great wealth to the province. New water systems helped increase irrigation. Olives and grapes had been popular for a long time. However, vineyards and orchards were destroyed during the last Punic war. They were also intentionally left to ruin because their products competed with those from Roman Italy. Instead, Africa Province became famous for producing large amounts of fine wheat, which was sent to many places, especially Rome. Ancient writers like Strabo, Pliny, and Josephus praised the quality of African wheat. The Medjerda river valley was said to be as productive as the Nile. Later, when Egypt started supplying wheat to Rome, grapes and olives began to reappear in the province's fields around the end of the 1st century. St. Augustine (354–430 AD) wrote that in Africa, lamps fueled by olive oil burned well all night, lighting up neighborhoods.

Evidence from artifacts and large mosaics in grand villas shows that a favorite sport of the wealthy farmers was hunting. Mosaics show well-dressed hunters on horseback chasing animals like jackals. Various wild birds were also hunted using traps.

Trade and Business

Ceramics and pottery had been important industries for centuries under the Phoenicians. They continued to be important. Both oil lamps and amphorae (containers with two handles) were made in large numbers. This pottery helped with the local production of olive oil. Amphorae were useful for transporting oil locally and for exporting it by ship. Many ancient olive presses have been found, which produced oils for cooking, food, and lamps. Ceramics were also shaped into small statues of animals, people, and gods, found often in local cemeteries. Later, terra-cotta plaques showing Bible scenes were made for churches. Much of this industry was in central Tunisia, for example, around Thysdrus (modern El Djem), an area with less fertile land but rich clay deposits.

Exporting large amounts of wheat, and later olive oils and wines, needed good ports. Some of these included: Hippo Regius (modern Annaba), Hippo Diarrhytus (modern Bizerte), Utica, Carthage, Curubis, Missis, Hadrumentum, Gummi, Sullectum, Gightis, and Sabratha. Marble and wood were shipped from Thabraca (modern Tabarka). Ancient groups involved in shipping exports could form navicularii, who were responsible for goods but also received special state benefits. Inland trade happened on Roman roads, built for both the Roman legions and for trade. A main road went from Carthage southwest to Theveste (modern Tébessa). From there, a road went southeast to Tacapes (modern Gabès) on the coast. Roads also followed the coastline. Buildings were sometimes built along these roads for travelers and traders.

Other products from Africa Province were also shipped out. An old industry in Carthage made a Mediterranean condiment called garum, a fish sauce with herbs, which was very popular. Rugs, wool clothing, and leather goods were also made. The royal purple dye, murex, first made famous by the Phoenicians, was produced locally. Marble, wood, and live mules were also important exports.

Local trade happened at mundinae (fairs) in rural centers on certain days, much like souks today. In villages and towns, macella (food markets) were set up. In cities with a special charter, the market was regulated by city officials called aediles, who checked measuring and weighing tools. City trading often took place in the forum, in covered stalls, or in private shops.

Explorations went south into the Sahara Desert. Cornelius Balbus, a Roman governor, took over Germa, the desert capital of the Garamantes people in 19 BC. These Berber Garamantes had long-term contact with the Mediterranean world. Although Roman trade with the Berber Fezzan continued, large-scale trade across the Sahara to the more populated lands south of the desert did not develop for many centuries.

Latin Culture and Berber People

How Cultures Mixed

People from all over the Roman Empire moved to Africa Province. These included merchants, traders, officials, and most importantly, retired soldiers. These veterans settled on farms given to them for their military service. A large Latin-speaking population grew, made up of people from many backgrounds. They lived alongside people who spoke Punic and Berber languages. Official empire business was usually done in Latin, leading to a situation where people spoke two or three languages. Roman security forces began to include local people, including Berbers. The Romans seemed to do things that helped people accept their rule.

One historian noted that Berbers accepted the Roman way of life more easily because Romans were tolerant of Berber religious beliefs. However, Roman culture did not spread evenly across Africa. Some groups of Berbers remained non-Romanized, even in areas like eastern Tunisia.

While most Berbers adapted to the Roman world, this doesn't mean they fully accepted it. Often, Roman cultural symbols existed alongside traditional local customs and beliefs. Roman ways didn't replace Berber culture but added to it.

Social Groups

The success of the Berber writer Apuleius was more of an exception. Many native Berbers adopted the wider Mediterranean influences in the province. Some married into Roman families or became important figures. However, most did not. There remained a social structure with the Romanized, the partly assimilated, and the unassimilated (many rural Berbers who didn't know Latin). Yet, among the "assimilated" could be very poor immigrants from other parts of the Empire. These imperial differences were on top of existing economic classes. For example, slavery continued, and some wealthy Punic nobles remained.

The fast pace and economic demands of city life could negatively affect the poor in rural areas. Large estates (latifundia) that grew crops for export were often managed for owners who lived elsewhere and used slave labor. These large farms took over lands previously worked by small local farmers. There were also disagreements and tensions between nomadic herders and settled farmers. The best lands were usually taken for planting, often by those with better social or political connections. These economic and social divisions sometimes led to conflicts, like the revolt in 238 AD.

Important People from Roman Tunisia

The Gordian Family

In 238 AD, local landowners started a revolt. They armed their workers and tenants, who entered Thysdrus (modern El Djem). There, they killed a greedy official and his guards. In open revolt, they declared the elderly Governor of Africa Province, Gordian I, and his son, Gordian II, as co-emperors. Gordian I had served in the Roman Senate and as a Consul. The current Emperor, Maximinus Thrax, was very unpopular. In Rome, the Senate supported the rebels from Thysdrus. When the African revolt failed, the Senate chose two of their own, Balbinus and Pupienus, as co-emperors. Then, Maximinus Thrax was killed by his own soldiers. Eventually, Gordian I's grandson, Gordian III, from Africa Province, became the Emperor of the Romans from 238–244 AD. He died on the Persian border.

Salvius Julianus: A Legal Mind

Julian's life shows the opportunities available to talented people from the provinces. It also gives us a look at Roman Law, which helped hold the Empire together. Julian likely came from a Latin-speaking family that had settled in Africa Province.

Salvius Julianus (around 100 – 170 AD), a Roman jurist (legal expert) and Consul in 148 AD, was born in Hadrumetum (modern Sousse, Tunisia). He was a teacher, and one of his students became the last head of an important school of Roman jurists. Julian held many high positions during his long career. He was highly respected as a jurist and is considered one of the best in Roman legal history. His main work was to organize the laws.

Julian served on the imperial council of three emperors: Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius. His life was during a very good time for Roman rule, with peace and wealth. Julian held many important senatorial offices. Later, he became the Roman governor of Germania Inferior and Hispania Citerior. At the end of his career, Julian became the Roman governor of his home, Africa Province. An inscription near Hadrumetum tells about his official life.

Emperor Hadrian asked Julian to revise an important legal document called the Praetor's Edict. This document was very influential in Roman Law. Julian organized its final form.

Later, Julian wrote his Digesta in 90 books. This work explained all of Roman Law.

In the 6th century, Julian's Digesta was used many times by those who created the Pandectae (also known as the Digest). This was a huge collection of legal knowledge, made under the Byzantine emperor Justinian I. The Pandect became a main source for studying Roman Law in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Little is known about Julian's personal life. He may have been related to the Roman emperor Didius Julianus. Julian likely died in Africa Province. Emperor Marcus Aurelius called him "our friend." Julian's fame grew over time, and later emperors praised him.

Lucius Apuleius: A Storyteller

Lucius Apuleius (around 125 – 185 AD) was a Berber author from Africa Province. He wrote in a new Latin style. He was a successful writer and religious figure in Carthage. He described himself as a full Berber, from Madaura (modern M'Daourouch). Many retired Roman soldiers, often from Africa themselves, lived in his hometown. His father was a local official and left him and his brother a good amount of money.

Apuleius studied in Carthage, Athens (philosophy), and Rome (public speaking). He also traveled to Asia Minor and Egypt. On his way back to Carthage, he became very ill in Oea (an ancient city near modern Tripoli). He recovered at the home of an old student friend. Apuleius later married Prudentilla, the wealthy widow of the house. Although the marriage seemed happy, some of her relatives accused him of using magic to win her over. At his trial, Apuleius defended himself with a speech that became his Apology. He was found innocent.

Apuleius and Prudentilla then moved to Carthage. He continued writing in Latin, covering Greek philosophy, public speaking, fiction, and poetry. He gained many followers, and several statues were put up in his honor. He was a brilliant public speaker, known as a "popular philosopher."

His most famous work of fiction is Metamorphoses, often called The Golden Ass. It's a clever and imaginative story set in Greece. The hero tries to use a sorceress's ointment to turn into an owl but becomes a donkey instead. He can no longer speak but can understand others. A famous part of the story is the tale of Cupid and Psyche. After many adventures as a donkey, the hero finally regains his human form by eating roses. The Egyptian goddess Isis helps him. In the end, the hero becomes a follower of Isis and Osiris.

Metamorphoses is seen as a unique story about religious experience in the ancient pagan world. Some scholars believe it teaches a religious lesson: Isis saves the hero from the empty things of this world to a life of happy service.

St. Augustine, who was also from Africa, mentioned Apuleius in his book The City of God. Augustine criticized Apuleius's ideas about spirits.

Many people at the time believed Apuleius used magic. He was interested in mystery religions, especially the cult of Isis. He held an important religious office in Carthage.

Apuleius used a Latin style called elocutio novella ("new speech"). This style mixed everyday language with older words. It was different from the more formal Latin used before. This "new speech" style also pointed towards how modern Romance languages would develop.

Christianity and its Challenges

Felicitas and Perpetua: Early Martyrs

The Roman Imperial cult was a public worship of the reigning Emperor as a divine leader. Sometimes, people were forced to show their loyalty to this state cult. Those who refused, especially Christians, could face death. Christians believed in one God, which went against the idea of worshipping the Emperor.

In Africa Province, two young Christian women, Felicitas and Perpetua, became famous. Felicitas was a servant to Perpetua, who was a noble. Felicitas was pregnant, and Perpetua was a nursing mother. Both were publicly killed by wild animals in the arena at Carthage in 203 AD. Felicitas and Perpetua became celebrated as saints among Christians. A respected writing, containing Perpetua's thoughts and visions, was read in churches across the Empire.

Important Christian Thinkers

Three important theologians (people who study religion) came from Africa Province: Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine.

Tertullian (160–230 AD) was born, lived, and died in Carthage. He was an expert in Roman law, became a Christian, and then a priest. His Latin books on theology were well-known. He helped explain an early understanding of the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). Later, Tertullian followed a very strict form of Christianity and was considered to have strayed from the main Church teachings.

Cyprian (210–258 AD) was the Bishop of Carthage and was killed for his faith. He was also a lawyer and a convert to Christianity. He saw Tertullian as his teacher. Many of Cyprian's writings offer kind moral advice. His book On Church Unity (251 AD) also became famous.

Augustine of Hippo: A Great Thinker

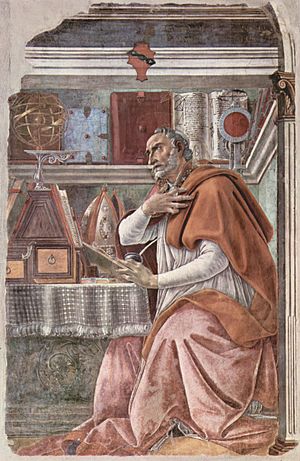

St. Augustine (354–430 AD), the Bishop of Hippo (modern Annaba), was born in Tagaste (modern Souk Ahras). His mother, St. Monica, was a strong believer and likely had Berber heritage. Augustine himself did not speak a Berber language. He received his higher education in Carthage. Later, while teaching in Milan, he followed Manichaean teachings. After a strong conversion to Christianity, Augustine returned to Africa. He served as a priest and later as bishop of Hippo. He wrote many works and became a major influence on Christian theology.

Augustine knew a lot about pagan philosophy from the Greek and Roman world. He criticized its weaknesses but also used it to explain Christianity. Although he studied the works of his fellow African writer, Apuleius, Augustine strongly disagreed with his understanding of spiritual things. In his famous book, The City of God, Augustine discussed Christian theology and history. He criticized the ancient Roman state religion but admired traditional Roman virtues. He believed that their good actions found favor with God. He also traced the history of Israel and explored the Christian gospels.

Augustine remains one of the most important and admired Christian theologians. His moral philosophy is still influential, for example, his ideas on the Just War doctrine, which helps decide if a military action is moral. His books, like The City of God and Confessions, are still widely read.

The Donatist Split

The Donatist split was a big problem for the Church. It happened after a harsh Roman persecution of Christians ordered by Emperor Diocletian (284–305 AD). An earlier persecution had caused arguments about whether to let Christians who had given up their faith under threat back into the church. Then, in 313 AD, the new Emperor Constantine I allowed Christianity to be practiced freely. This change caused confusion in the Church. In Northwest Africa, it made the divide worse between wealthy city Christians who supported the Empire and poor rural Christians who were very devout. Generally, rural Christian Berbers tended to be Donatists, while more Romanized urban Berbers were Catholic. The Church struggled to handle this challenge. The Donatists were strong in southern Numidia, and the Catholics were centered in Carthage.

One issue was whether a priest could perform his duties if he wasn't personally worthy. The Donatists created their own churches to practice a stricter form of ritual purity, believing they were like ancient Israel.

Berber Uprisings

The armed conflicts described below might be different from the revolt of Tacfarinas in 17–24 AD. Some historians believe these conflicts were not just class struggles or Berber versus Roman rebellions, though they had elements of both. They were more likely "a dynastic struggle pitching one lot of African nobles, with their tribes, against another." These nobles often had divided loyalties. They acted as go-betweens for Roman Empire leaders and local tribal life, which was mostly rural. These tribes lived by farming or herding and were far from the educated cities. The nobles offered protection to their Berber subjects in exchange for tribute and military service. This protection included safety from attacks by other tribes and from slave raiders from the cities. The nobles needed money and armed power, but also needed to be able to communicate with Roman leaders. If a noble's status changed unexpectedly, it could lead to a desperate fight.

Another view is that the nobles Firmus and Gildo continued the struggle of the commoner Tacfarinas. This view sees the fight as involving class issues and pitting Berbers against Romans. In the 350 years between Tacfarinas and these later revolts, the struggle had continued. Both Firmus and Gildo gained support from the poor by joining with the dissenting Donatist churches and their radical movement called circumcellion. These conflicts were part of a long effort by native farmers to reclaim their lands, which had been taken by the Romans after military victories. Some historians see this as an ethnic struggle for fairness and justice.

Firmus (died 375 AD) and Gildo (died 398 AD) were half-brothers from a Berber landowning family. The Roman government in Constantinople recognized their family. Their father, Nubel, was known as a "little king" of a Mauri tribe of Berbers. Nubel was an important leader in Berber tribal politics, a Roman official with high connections, and a private owner of large lands. He was also a commander of Roman cavalry and built a local Christian church. Nubel had six sons: Firmus, Sammac, Gildo, Mascezel, Dius, and Mazuc. The names of Nubel's children show a mix of Roman and Berber cultures. For example, Gildo means "ruler" in Berber, while Firmus and Dius are Latin names.

Firmus's Revolt

Sammac, one of Nubel's sons, owned a fortified estate like a city, inhabited by local Mauri Berbers. Sammac was a close friend of the Roman Count of Africa. However, his brother Firmus had Sammac killed for unknown reasons. Firmus tried to justify his actions, but the Roman Count blocked him and reported him to higher Roman officials. Cornered, Firmus started a revolt. Historians called Firmus a "national enemy" and "insurgent." The local bishop Augustine of Hippo called him a "barbarian king."

Firmus gained support for his revolt (372–375 AD) from three of his brothers and from Mauri tribal allies. He also attracted support from the Donatist Christian churches and people who were against Rome and taxes. Firmus likely called himself King of Mauritania. He may have championed the cause of the rural poor. However, his younger brother Gildo remained loyal to Rome. A strong Roman general, Count Theodosius, led a Roman force against Firmus. The fighting caused problems with local loyalties. In the battles that led to Firmus's defeat, Gildo helped the Romans.

Gildo's Defiance

A decade later, in 386 AD, Gildo became the Roman Count of Africa, the commander of its military forces. Gildo's appointment was due to his long connection with Theodosius's family, whose son was now Emperor Theodosius I in the East. Gildo's daughter also married into the imperial family. The Roman Empire was divided into East and West. Italy's main source of grain was Gildo's Africa. Gildo wanted to deal directly with Emperor Theodosius in Constantinople and suggested transferring Africa to the East. This angered Stilicho, a powerful Roman general in the West.

When Emperor Theodosius I died in 395 AD, Gildo "gradually waived his loyalty." His rule relied on Mauri Berber alliances and supported Donatist churches. In 397 AD, Gildo declared his loyalty to the new, weak eastern Emperor. Gildo started his rebellion by stopping wheat shipments to Rome. He may have taken imperial lands and given them to his troops and the Donatist radicals. Ironically, Gildo's defiance was opposed by his own brother Mascezel, who served Stilicho. The conflict between the brothers was very bitter. Gildo failed to escape by ship and died captive in 398 AD. Mascezel died soon after. Gildo's daughter raised her children in Constantinople at the imperial court. The Vandals crossed into Africa in 429 AD.

These events show a powerful Berber-Roman family in the 4th century within the Roman Empire. They also show the complex loyalties of Africans at that time. Or, it could simply be a story of the poor seeking leaders to fight for their land.

Later Roman Times

New Berber Kingdoms

The Decline of the Roman Empire in the West was a slow process with shocking events. After 800 years of safety, Rome fell to the Visigoths in 410 AD. By 439 AD, Carthage was captured by the Vandals. These changes were very difficult for Roman citizens in Africa Province, including Romanized Berbers who relied on the fading Imperial economy.

However, other Berbers saw a chance for a better life or even freedom as Rome declined. Berbers living in urban poverty or as rural workers within the empire, or as independent herders and tillers outside its borders, found new opportunities. For example, they could gain access to better land and trading terms. The lack of Roman authority led to new Berber states. These states appeared inland, along the borderlands between the steppe and the cultivated land, not along the coast in the old Roman cities. This "pre-Sahara" zone ran along the mountains and plains that separated the well-watered parts of the Maghreb from the Sahara desert. Here, Berber tribal chiefs used force and negotiation to create new governing powers.

Eight of these new Berber states have been identified across Northwest Africa. These kingdoms served two different groups: the Romani, who were settled citizens, and the Mauri, who were Berber tribes. The Romani provided city resources and a tax system that needed civil administration. The Mauri provided goods from the countryside and met military needs. This mix of cultures and functions was central to the Berber states. For example, a leader in one kingdom was called rex gent(ium) Maur(orum) et Romanor(um) – "King of the Mauri and of the Romans."

In the Kingdom of Ouarsenis, thirteen large burial monuments called Djedars were built in the 5th and 6th centuries. Many were square, 50 meters wide and 20 meters high. These monuments show a long tradition of large Northwest African royal tombs. Some have Christian symbols, though the inscriptions are hard to read. The Djedars show how an ancient Berber building tradition was adapted to a Christian, Romanized environment.

However, it's not fully clear how Christianity developed among independent Berbers after Roman rule. Christianity never completely replaced the old pagan beliefs of Berbers. Also, Christianity among the Berbers did not achieve lasting unity among its different groups.

Under the Byzantines, some Berber groups near the imperial power became nominal vassal-states, pledging loyalty to the Empire. The Byzantines tried to control these rural groups through talks, trade, or military displays. Roman cities like Tiaret, Altaya, Tlemcen, and Volubilis survived into the 7th century, where Christians wrote in Latin. Other Berber groups on the edge of the settled regions remained fully independent.

The Vandal Kingdom

In the 5th century, the western Roman Empire was in sharp decline. A Germanic tribe called the Vandals had already traveled across the Empire to Hispania (modern Spain). In 429 AD, under their king Gaiseric (who ruled from 428–477 AD), the Vandals and their allies, the Alans, about 80,000 people, traveled 2000 kilometers from Spain across the straits and east along the coast to Numidia, west of Carthage. The next year, the Vandals surrounded the city of Hippo Regius. In 439 AD, the Vandals captured Carthage, which became the center of their Germanic kingdom.

The western Roman capital recognized Gaiseric's rule in 442 AD. However, the eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) tried to reconquer Africa several times. In 468 AD, a large Byzantine fleet approached Carthage. Gaiseric asked for time to consider surrendering. When the wind changed, Vandal fire ships were sent into the fleet, destroying it. After promising freedom of worship for Catholics, Gaiseric made a peace treaty with the Byzantines in 474 AD, which lasted about sixty years.

The arrival of these Germanic conquerors was very unexpected in North Africa. At first, many Berbers fought the Vandals. After the Vandals conquered the area, Berber forces remained the only military threat to them. However, the Vandals also made alliances with the Berbers to secure their control of the land. In 455 AD, Gaiseric sailed with an army to the city of Rome.

In terms of religion, the Vandals tried to convert the urban Catholic Christians of Africa to their Arian beliefs. The Vandal government sent Catholic clergy into exile and took over Catholic churches. In the 520s, they even persecuted Christians, but without success. The Berbers stayed out of these religious conflicts. Overall, Vandal rule lasted 94 years (439–533 AD).

The Vandals provided security and governed lightly, so the former Roman province prospered at first. Large estates were taken, but former owners often managed them. Roman officials handled public affairs, and Roman law courts continued to operate, with Latin used for government business. However, Romans at the royal court in Carthage would wear Vandal clothing. Farming produced more than enough food, and trade thrived in the towns. But because the Vandals wanted to keep their higher status, they refused to marry or mix with the advanced Roman culture. This meant they failed to fully maintain the complex civil society. Berber groups beyond the border grew stronger and more dangerous to the Vandal rulers.

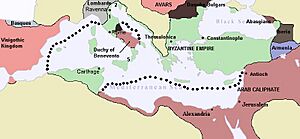

The Byzantine Empire Returns

The Eastern Romans, also known as the Byzantine Empire, eventually took back Rome's Africa province during the Vandalic War in 534 AD. Their famous general Belisarius led this reconquest. The Byzantines rebuilt forts and border defenses and made treaties with the Berbers. However, for many decades, security and wealth were uncertain and never fully returned. Direct Byzantine rule did not extend far beyond the coastal cities. The African interior remained under the control of various Berber tribal groups.

In the early 7th century, some new Berber groups converted to Catholicism, joining Berbers who were already Christian. However, other Berbers remained loyal to their old gods.

In the early 7th century, the Byzantine Empire faced serious problems. For centuries, Byzantium's biggest enemy had been the Sassanid Persians, and they were often at war. But in the 7th century, things changed dramatically. Religious disagreements within the Empire and a change in emperors weakened the Byzantines. The Persians invaded the Byzantine Empire, taking many cities. The end of the Empire seemed near.

It was the son of the Byzantine governor of Carthage, Heraclius (575–641 AD), who would save the empire. Heraclius sailed to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, and became Emperor in 610 AD. He began to reorganize the government and build defenses. Despite this, the Persians continued their invasion. Heraclius then moved a Roman army by ship and outflanked the Persians. By 627 AD, Heraclius was marching on their capital. In 628 AD, the Persian Shah was killed.

As a result, Persia was in chaos. The Byzantines were able to retake their provinces of Egypt and Syria. However, with the Romans' return, the old religious disagreements between local Christians in Egypt and the official Church also returned. Emperor Heraclius tried to find a religious compromise, but it satisfied no one, and the disagreements continued.

Meanwhile, new events were happening on the imperial border. To the south, Arab peoples began to rise under the influence of a new religion, Islam. In 636 AD, the Arab Islamic armies decisively defeated the Byzantine forces. Soon, the recently regained Roman provinces of Syria and Egypt would be lost again by the Byzantines, this time permanently, to the emerging Islamic power.

After the Arab invasion and occupation of Egypt in 640 AD, Christian refugees fled west to the Byzantine-ruled Exarchate of Africa (Carthage). Here, serious disputes arose within the Catholic churches over religious doctrines, with St. Maximus the Confessor leading the orthodox Catholics.

|

See also

- Berber people

- Berber languages

- Utica

- Carthage

- Salvius Julianus

- Apuleius

- Felicitas and Perpetua

- Tertullian

- Cyprian

- Augustine

- Firmus

- Gildo

- Africa Province

- Diocese of Africa

- Exarchate of Africa

- Praetorian prefecture of Africa

- North Africa during the Classical Period

- History of Tunisia

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |