History of Tunisia facts for kids

The present day Republic of Tunisia, also known as al-Jumhuriyyah at-Tunisiyyah, is located in North Africa. It sits between Libya to the east, Algeria to the west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north. Tunis is the capital and largest city, with over 800,000 people. It is close to the ancient city of Carthage.

Tunisia's land has stayed mostly the same throughout history. However, in ancient times, there were more forests in the north. Long ago, the Sahara desert to the south was not as dry as it is today.

The north has mild, rainy winters and hot, dry summers, typical of a Mediterranean climate. This area is wooded and fertile. The Medjerda river valley, northeast of Tunis, is now valuable farmland. Along the eastern coast, the central plains have a moderate climate with less rain but heavy dews. These coastal areas are used for fruit orchards and grazing animals. Near the Algerian border, you'll find Jebel ech Chambi, the country's highest point at 1,544 meters. Further south, a line of salt lakes stretches across the country from east to west. Beyond that lies the vast Sahara desert, including the sand dunes of the Grand Erg Oriental.

Contents

- Ancient History of Tunisia

- Carthage: A Powerful Ancient City

- Roman Province of Africa

- Fall of Roman Empire and New Kingdoms

- Umayyad Caliphate in Ifriqiya

- Aghlabid Dynasty under the Abbasids

- Fatimids: Shi'a Caliphate, and the Zirids

- Norman Africa

- Almohads (al-Muwahiddin)

- Hafsid Dynasty of Tunis

- Ottoman Caliphate and the Beys

- Modernity and the French Protectorate

- Tunisian Republic

- The "Dignity Revolution"

- Presidency of Kais Saied

- See also

Ancient History of Tunisia

First People and Early Cultures

The earliest signs of humans in Tunisia are Stone Age tools found near Kelibia. These tools are about 200,000 years old. Later, the Capsian culture, named after Gafsa in Tunisia, existed from about 10,000 to 6,000 BC. They used stone blades and tools. People of this culture moved seasonally.

Ancient Saharan rock art shows designs, animals, and humans. These artworks are linked to the Berbers and early Africans from the south. Animals like large buffalo, elephants, and giraffes are shown. Some human figures are dancing or driving chariots.

Around 5,000 years ago, a new culture developed among the early Berbers in Northwest Africa. They started farming, raising animals, and making pottery. They grew wheat, barley, and beans. They also used ceramic dishes daily. These early Berbers were farmers with strong ties to their animals and had special cemeteries. This was over a thousand years before the Phoenicians arrived. Wealth among nomadic herders was measured by the number of sheep, goats, and cattle a person owned.

We don't know much about the religion of the ancient Berbers, except for their burial customs. Almost 60,000 tombs have been found in the Fezzan region alone. The Medracen tomb in Algeria, built for a Berber king, still stands today. Berbers believed that divine power was in nature, like in water or stones. Fish symbols, often seen in mosaics, were used to ward off evil. Some Berbers sacrificed to the sun and moon. Later, they adopted ideas from ancient Egyptian religion and Punic religion.

Egyptian writings from early dynasties mention "Libyans," who were Berbers of the "western desert." Ramses II (1279–1213 BC) even had Libyan soldiers in his army. Paintings from the 13th century BC show Libyan leaders in fine robes with ostrich feathers. A Berber from the Meshwesh tribe, Osorkon the Elder, became the first Libyan pharaoh. Later, his nephew Shoshenq I (945–924 BC) founded Egypt's Twenty-second Dynasty. For centuries, Egypt was ruled by a system based on Libyan tribal groups.

Farther west, some Berbers were known as Gaetulians, Numidians, or Mauri. These groups interacted with Phoenicia, Carthage, and later Rome. Before this, rural Berbers lived in small farming villages. They might move seasonally to find new pastures for their animals. It is thought that fighting between clans kept Berbers from forming larger political groups. However, the threat from Carthage encouraged villages to unite under strong leaders.

A 2nd-century BC inscription from the Berber city of Thugga (modern Dougga) shows a complex city government. The Berber title GLD (like a paramount tribal chief) was the main ruling office. This position rotated among leading Berber families. Around 220 BC, three large Berber kingdoms existed: the Mauri in modern Morocco, the Masaesyli in northern Algeria, and the Massyli near Carthage. Berber identities remained strong even under Carthaginian and Roman rule.

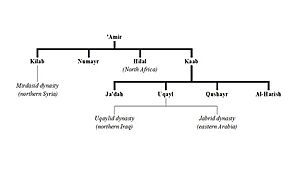

During the early Islamic era, Berber tribes were divided into two main groups: the Butr and the Baranis. The Arabs often recruited from the Butr. Later, some legends claimed Berbers descended from ancient Arab tribes, but scholars like Ibn Khaldun rejected this. This legend, however, played a role in the long process of Arabization.

In medieval Islamic history, Berbers are grouped into three major tribes: the Zanata, the Sanhaja, and the Masmuda. The Zanata allied more with the Arabs and became more Arabized. Sanhaja are spread across the Maghrib, including the sedentary Kabyle and the nomadic Tuareg. The Masmuda are sedentary Berbers in Morocco, and are the most populous modern Berber group.

Medieval events in Ifriqiya (Tunisia) and al-Maghrib often involved these tribes. The Kutama tribes, linked to the Kabyle Sanhaja, helped establish the Fatimid Caliphate. The Zirids, who followed the Fatimids in Ifriqiya, were also Sanhaja. The Almoravids began among the Lamtuna Sanhaja. The Almohads came from the Masmuda tribe. The Hafsid dynasty of Tunis also originated from the Masmuda.

Migrating Peoples and New Arrivals

History began with traders sailing from the eastern Mediterranean. Later, colonists followed, settling along the coasts of Africa, Spain, and on islands.

New technologies and economic growth in the eastern Mediterranean increased the need for metals. Phoenician traders found these metals in Spain, which boosted trade. The Phoenician city of Tyre managed much of this trade and set up trading posts along the way.

Around 3,000 years ago, the Levant and Greece were very prosperous, leading to population growth. Sometimes, political problems caused economic hardship. City-states began sending groups of young people to settle in less populated areas. Many more colonists came from Greece than from Phoenicia.

These migrants found opportunities in the western Mediterranean. They could reach these lands easily by ship. The Greeks arrived later, settling in southern France, southern Italy (including Sicily), and eastern Libya. Earlier, the Phoenicians settled in Sardinia, Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Sicily, and Tunisia. In Tunisia, they founded Carthage, which would eventually rule other Phoenician settlements.

Throughout Tunisia's history, many people have arrived and settled among the Berbers. More recently, the French and many Italians came. Before them, the Ottoman Turks brought their multi-ethnic rule. Even earlier, the Arabs brought their language and the religion of Islam. Before the Arabs came the Byzantines and the Vandals. Over 2,000 years ago, the Romans governed the region for a long time. The Phoenicians founded Carthage almost 3,000 years ago. People also migrated from the Sahel region of Africa. Perhaps 8,000 years ago, people were already living there, and the early Berbers mixed with them, leading to the development of the Berber people.

Carthage: A Powerful Ancient City

Founding of Carthage

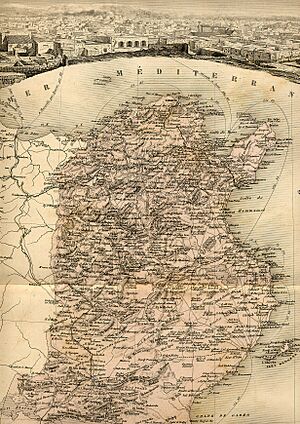

The city of Carthage, whose ruins are near modern Tunis, was founded by Phoenicians from the eastern Mediterranean coast. Its name, Qart Hadesht in the Punic language, means "new city." This is similar to the Arabic "Qarya Haditha," meaning "Modern Village/City."

A Greek historian named Timaeus of Taormina said Carthage was founded in 814 BC. This date is generally accepted. Older Phoenician cities like Utica and Gades were founded earlier, but archaeology hasn't confirmed those dates.

Tyre, a major Phoenician city, settled Carthage to have a permanent trading post. Legends say Queen Elissa, also called Dido, founded the city after fleeing Tyre. The Roman poet Virgil wrote about Dido in his epic poem, the Aeneid.

Carthage Becomes a Power

By the mid-6th century BC, Carthage became a strong, independent sea power. Under Mago (around 550–530 BC) and his family, Carthage became the most important Phoenician colony in the western Mediterranean.

Carthage formed trading partnerships with the Numidian Berbers to the west and east. They also had trading posts in Sardinia, Sicily, Ibiza, and Spain. Carthage was also allied with the Etruscans, who ruled a powerful state north of early Rome.

A Carthaginian sailor named Himilco explored the Atlantic coast north of the straits around 500 BC. Carthage soon took over the tin trade from the Iberian city of Tartessus. Another explorer, Hanno the Navigator, explored the African coast to the south. Carthaginian traders kept their trade routes secret and tried to keep Greeks out of the Atlantic.

In the 530s BC, there was a naval war between Phoenicians, Greeks, and their allies. The Greeks lost Corsica and Sardinia. The Roman Republic and Carthage signed a treaty in 509 BC to define their trade areas.

Rivalry with Greece

The strong presence of Greek traders in the Mediterranean led to conflicts over trade influence, especially in Sicily. When Phoenicia was conquered in the east, many Phoenician colonies came under Carthage's leadership. In 480 BC, Hamilcar, Mago's grandson, led a large army to Sicily to fight Syracuse, a Greek colony. The Greeks won the Battle of Himera. A long struggle followed, with battles between Syracuse and Carthage. Later, Carthage defeated the Greek leader Agathocles near Syracuse. Agathocles then tried to attack Carthage directly at Cape Bon, which scared the city. But Carthage defeated him again. Greece was busy conquering the Persian Empire, and eventually, Rome became Carthage's new rival in the western Mediterranean.

During this time, Carthage expanded its trade, venturing south into the Sahara. It also strengthened its markets along the African coast, in southern Spain, and on Mediterranean islands. Carthage also took direct control over the Numidian Berber people in the lands around the city, which became very rich.

Carthaginian Religion

The Phoenicians of Tyre brought their customs and beliefs to Northwest Africa. Their religious practices were similar to those in Canaan, which shared traits with other ancient Semitic cultures. In Canaan, the supreme god was El, meaning "god." The important storm god was Baal, meaning "master."

After moving to Africa and living alongside Berber tribes, the Phoenician religion in Carthage changed over time. The gods worshipped depended on the specific city or tribe.

Carthage's Government

Carthage's government was likely based on Tyre's, but Carthage didn't have kings. An important position was the Suffets, similar to judges. The Suffet was an executive leader and also had a judicial role. They were elected by citizens for a one-year term, usually two at a time, much like the Roman Consuls. A key difference was that Suffets had no military power. Carthaginian generals led mercenary armies and were elected separately.

Aristotle, a Greek philosopher, described Carthage's government as a "mixed constitution," combining elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Later, Polybius described the Roman Republic in a similar way.

Carthage also had a council of elders, similar to the Roman Senate, who advised the Suffets. This body had several hundred wealthy members who served for life. From these members, 104 judges were chosen. These judges later judged not only generals but also other officials. Aristotle thought the 104 judges were very important.

Popular assemblies also existed in Carthage. If the Suffets and the council couldn't agree, they might ask the assembly to vote. The assembly members didn't need to be wealthy or of noble birth.

The Greeks admired Carthage's government. Aristotle saw only one flaw: that focusing on wealth led to an oligarchy (rule by a few wealthy people). The people of Carthage were not very involved in politics. Carthage was very stable, with few tyrants. Aristotle noted that "The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal." Only after Rome defeated Carthage did the people show interest in reform.

After the Second Punic War, Hannibal, a famous military leader, was elected Suffet in 196 BC. He tried to reform the government, but corrupt officials blocked him. They even accused him of plotting war against Rome, forcing Hannibal to leave Carthage.

Punic Wars with Rome

The rise of the Roman Republic led to a long rivalry with Carthage for control of the western Mediterranean. They had signed treaties, but their opposing interests eventually led to conflict.

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) began in Sicily. It became a naval war, which Rome learned to fight and won. Carthage lost Sardinia and part of Sicily. After their defeat, a mercenary revolt threatened Carthage, but they survived it.

The Second Punic War (218–201 BC) started over a dispute in Spain. Hannibal led his armies over the Alps into Italy. At first, Hannibal won major victories against Rome, like at Trasimeno and Battle of Cannae. These battles almost destroyed Rome's ability to fight. However, most of Rome's Italian allies stayed loyal, and Rome rebuilt its military. Hannibal stayed in southern Italy for many years. His brother Hasdrubal tried to reinforce him in 207 BC but failed. Meanwhile, Roman armies under Scipio (later Africanus) defeated Carthaginian power in Spain by 206 BC. In 204 BC, Rome landed armies near Carthage, forcing Hannibal to return. One Numidian king, Syphax, supported Carthage, while another, Masinissa, supported Rome. At the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, Scipio Africanus defeated Hannibal, ending the long war. Carthage lost its trading cities and much of its influence over the Numidian Kingdoms. It also had to pay a large amount of money to Rome. Carthage recovered, which worried Rome greatly.

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) began when Carthage refused to change its agreement with Rome. Roman armies besieged Carthage, which refused to negotiate. Eventually, Carthage was destroyed, and its citizens were enslaved.

Afterward, the region (modern Tunisia) became the Roman Province of Africa. Carthage was later rebuilt by the Romans. Long after the fall of Rome, Carthage would be destroyed again.

Roman Province of Africa

Republic and Early Empire

The Africa Province (mostly modern Tunisia and eastern coastal areas) saw military campaigns by famous Romans during the late Republic. Gaius Marius celebrated a victory after defeating Jugurtha, the Numidian king. Marius was the first Roman general to recruit landless citizens into his army. Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who later became a dictator, helped end the war by persuading King Bocchus I to hand over Jugurtha.

In 47 BC, Julius Caesar landed in Africa to pursue Pompey's army, which was based at Utica and supported by the Numidian King Juba I. Caesar's victory at the Battle of Thapsus almost ended that phase of the civil war. Caesar then took over Numidia (eastern Algeria).

Augustus (ruled 31 BC to 14 AD) controlled the Roman state after the civil war that ended the Roman Republic. He established the Roman Empire.

Around 27 BC, Augustus restored Juba II as King of Mauretania (east of the Province of Africa). Juba, educated in Rome, wrote books about African culture and history. He married Cleopatra Selene II, the daughter of Anthony and Cleopatra. After his reign, his kingdom became Roman provinces.

Carthage Reborn

The rebuilding of Carthage began under Augustus, and the city thrived in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Carthage became the capital of the Africa Province. The province became wealthy from its rich agriculture, especially olives, grapes, and wheat. Marble, wood, and mules were also important exports. New towns were founded, and many Punic and Berber settlements prospered.

Expeditions went south into the Sahara. In 19 BC, the Roman governor Cornelius Balbus occupied Gerama, the desert capital of the Garamantes. These Berber Garamantes had long-standing contact with the Mediterranean.

People from all over the Empire moved to Africa Province, including retired soldiers who settled on farms. A large Latin-speaking population developed, living alongside those who spoke Punic and Berber. The local population eventually joined the Roman security forces. The Romans were tolerant of Berber religions, which helped locals accept their rule. The Province of Africa became integrated into the Empire's economy and culture, with Carthage as a major city.

Apuleius (around 125–185 AD) was a successful writer and lawyer in Latin-speaking Carthage. He was a Berber from Madaura. He studied in Carthage, Athens, and Rome. He wrote philosophy, rhetoric, and poetry, and statues were built in his honor. Apuleius's writing style was new and influenced the development of modern Romance languages. He was also interested in mystery religions.

Many native Berbers adopted Roman influences, intermarrying or joining the local aristocracy. However, most did not. There was a social hierarchy of Romanized, partly assimilated, and unassimilated people, many of whom were Berbers. Slavery continued, and wealthy Punic aristocrats remained. The demands of urban life negatively affected the rural poor. Large estates, often using slave labor, took over land previously farmed by small local farmers. Tensions also grew between nomadic herders and settled farmers. These social divisions led to revolts and religious conflicts.

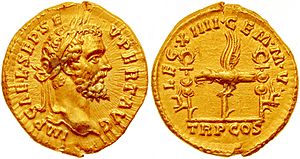

Emperors from Africa

Septimus Severus (145–211 AD), who ruled from 193–211 AD, was born in Lepcis Magna (now Libya). He had mixed Punic ancestry. His 18-year reign was known for military campaigns. His wife, Julia Domna, was from Syria. After Severus, his son Caracalla became Emperor. Caracalla's edict in 212 AD granted citizenship to all free people in the Empire. Later, two of Severus's grand-nephews also became Emperors. Emperor Macrinus (217–218 AD) came from Mauretania (modern Algeria).

There were also Roman Emperors from the Africa Province. In 238 AD, local landowners revolted and proclaimed the aged Governor, Gordian I, and his son, Gordian II, as co-emperors. The Roman Senate supported them. When the African revolt failed, the Senate elected two of their own as co-emperors. Eventually, Gordian I's grandson, Gordian III (225–244 AD), became Emperor of the Romans.

Christianity and the Donatist Schism

Two important Christian thinkers came from the Province of Africa. Tertullian (160–230 AD) was born, lived, and died in Carthage. He was a priest whose Latin books were well-known.

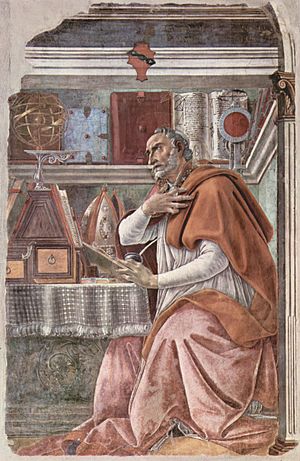

St. Augustine (354–430 AD), Bishop of Hippo (modern Annaba), was born in Numidia. His mother, St. Monica, was likely of Berber heritage. Augustine studied in Carthage. He became a church leader and wrote many important works, including The City of God and Confessions. He is still one of the most admired Christian theologians.

The Donatist schism was a major problem for the Church. It happened after a severe Roman persecution of Christians. In 313 AD, Emperor Constantine I granted tolerance to Christianity. This led to confusion in the Church, especially in Northwest Africa. It highlighted differences between wealthy city Christians, who aligned with the Empire, and poor rural Christians, who had social and political disagreements.

Christian Berbers often became Donatists, while some more Romanized Berbers were Catholic. The Donatists focused on strict ritual purity. Augustine condemned the Donatists for rioting. The conflict lasted for a long time, with Donatism eventually declared a heresy in 405 AD.

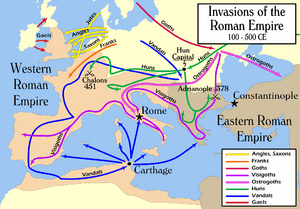

Fall of Roman Empire and New Kingdoms

Vandal Kingdom

In the 5th century, the western Roman Empire was declining. Carthage and the Roman province of Africa were captured in 439 AD by the Vandals under Gaiseric (ruled 428–477 AD). This became the center of their Germanic kingdom. The Roman capital recognized their rule in 442 AD. In 455 AD, the Vandals sailed to Rome, occupied it without resistance, and looted it.

The Vandals tried to convert the Catholic Christians of Africa to their Arian belief. They exiled clergy and took over churches. In the 520s, they even persecuted Christians, but without success. The Berbers stayed out of these religious conflicts. Vandal rule lasted 94 years.

The Vandals provided security and governed lightly at first. The former Roman province prospered. Roman officials and law continued, and Latin was used for government. Agriculture thrived, and trade flourished. However, the Vandals wanted to keep their superior status and refused to intermarry or mix with the Roman culture. This led to problems, and they failed to maintain a strong social order. Berber groups beyond the frontier grew more powerful and caused trouble.

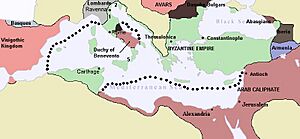

Byzantine Empire

The Eastern Romans, or Byzantine Empire, recaptured Northwest Africa in 534 AD under their general Belisarius. The Byzantines rebuilt forts and border defenses. They also made treaties with the Berbers. However, security and prosperity were never fully restored for many decades. Byzantine rule mostly stayed in coastal cities, while the interior remained under Berber control.

In the early 7th century, some Berber groups converted to Catholicism. In the 540s, the Catholic Church in Africa faced new religious disputes.

In the early 600s AD, the Byzantine Empire faced major crises. For centuries, their main enemy had been the Sassanid Persians. But in the 7th century, religious disagreements and a change in emperors weakened the Byzantines greatly. The Persians invaded, taking many Byzantine provinces.

It was a leader from Carthage, Flavius Heraclius Augustus, who helped restore the Empire. He was the son of the Exarch of Carthage. He sailed to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, and became Emperor in 610 AD. He reorganized the government and built defenses. The Persians continued their invasion, taking Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria. Heraclius then took a big risk, moving his army by ship to outflank the Persians. By 627 AD, he was marching on their capital. The Persian king was killed, and the Byzantines retook their provinces.

However, religious disagreements returned. Emperor Heraclius tried to find a compromise, but it didn't work. Then, to the south, Arab Islamic armies began to rise, united by the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. In 636 AD, the Arabs decisively defeated the Byzantine forces at the Battle of Yarmuk.

After the Arab invasion of Egypt in 640 AD, Christian refugees came west to the Exarchate of Africa (Carthage). There were serious disputes within the Catholic churches over different Christian doctrines.

Umayyad Caliphate in Ifriqiya

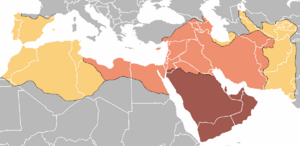

By 661 AD, the Umayyads firmly controlled the new Muslim state from Damascus. The Caliph Mu'awiya saw the lands west of Egypt as part of the Muslim struggle against the Byzantine Empire.

Islamic Conquest

In 670 AD, an Arab Muslim army led by Uqba ibn Nafi entered the region of Ifriqiya (the Arabic name for the former Province of Africa). The Arabs bypassed Byzantine forts along the coast. In the drier south, they established Kairouan as their base and began building its famous Mosque. From 675 to 682 AD, Dinar ibn Abu al-Muhadjir commanded the army. In the late 670s, this army defeated Berber forces led by Kusaila, who was captured.

In 682 AD, Uqba ibn Nafi took command again. He defeated a Berber alliance and marched west, reaching the Atlantic coast. However, Kusaila escaped and led a new Berber uprising, killing Uqba. Kusaila then formed a large Berber kingdom. But Zuhair b. Qais, Uqba's deputy, gathered tribes from Cyrenaica to fight for Islam. In 686 AD, he defeated Kusaila's kingdom.

Under Caliph 'Abd al-Malik (685–705 AD), the Umayyad conquest of North Africa was almost complete. A new army of 40,000 was assembled in Egypt, led by Hassan ibn al-Nu'man. The Byzantines had been reinforced. The Arab Muslim army quickly attacked and captured Carthage.

However, the Berbers continued to fight fiercely, led by a woman called the prophetess ["al-Kahina" in Arabic], whose real name was "Damiya". Damiya defeated the Muslim armies, forcing al-Nu'man to retreat. The Byzantines then reoccupied Carthage. Unlike Kusaila, Damiya did not create a larger state. Some think she ravaged the region to make it unattractive to raiders. From Egypt, the Caliph reinforced al-Nu'man in 698 AD, who re-entered Ifriqiya. Damiya fought again but lost and was killed.

In 705 AD, Hassan b. al-Nu'man stormed Carthage, destroying it. Utica suffered a similar fate. Near Carthage's ruins, he founded Tunis as a naval base. Muslim ships began to control the Mediterranean coast, leading to the final Byzantine withdrawal from al-Maghrib. Al-Nu'man was replaced by Musa ibn Nusair, who completed the conquest of al-Maghrib. He took Tangier and appointed the Berber Tariq ibn Ziyad as its governor.

The Role of Berbers

The Berber people, also known as the Amazigh, converted to Islam in large numbers and became part of the Arab Muslim society. Professor Hodgson notes that Berbers played a role in the west similar to that of Arabs elsewhere in Islam. For centuries, Berbers lived as semi-nomads in or near dry lands, keeping their unique identity.

Some argue that Berbers simply copied the success of the Arab Muslims. However, Professor Abdallah Laroui believes that Berbers created their own independent role. He says that from the 1st century BC to the 8th century AD, Berbers constantly tried to rebuild their kingdoms. By choosing to ally with the Arabs rather than Europe, Berbers knowingly decided their future. They embraced Islam as a way to achieve national liberation and independence.

The languages of the Semitic Arabs and the Berbers both belong to the same world language family, Afro-Asiatic. This linguistic connection might have shared deeper cultural and religious links.

Long before and after the Islamic conquest, there was a popular sense of a strong cultural connection between Berbers and the Semites of the Levant. These claims of ancient ancestry might have helped Berbers demand equal standing with the Arab invaders within Islam.

From Cyrenaica to al-Andalus, the somewhat Arabized Berbers stayed connected for centuries. They developed distinct features within Islam. For example, while most Islamic scholars adopted the Hanafi or Shafi'i schools of law, Berbers in the west chose the Maliki madhhab (school of law).

Other reasons for Berber conversion included the early flexibility in religious duties and the chance to join armies of conquest, sharing in the spoils. In 711 AD, the Berber Tariq ibn Ziyad led the Muslim invasion of Spain. Many Arabs who settled in al-Maghrib were religious and political dissidents, often Kharijites, who supported egalitarian ideas. These ideas were popular among Northwest African Berbers. The Arab conquest and Berber conversion to Islam followed a long period of social division in the old province of Africa, where the Donatist schism played a role. Berbers were initially drawn to the Arabs because of their shared connection to the desert.

After the conquest and widespread conversion, Ifriqiya became a natural center for an Arab-Islamic government in Northwest Africa. It had the most developed urban, commercial, and agricultural infrastructure, which was essential for the spread of Islam.

Aghlabid Dynasty under the Abbasids

Before the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus (661–750 AD), revolts by Kharijite Berbers in Morocco disrupted the entire Maghrib. Although the Kharijites didn't create lasting governments, their revolt had lasting effects. Direct rule by the Caliphs over Ifriqiya became impossible, even after the new Abbasid Caliphate was quickly established in Baghdad in 750 AD. After several generations, a local Arabic-speaking aristocracy emerged that resented the distant caliphate's interference.

Political Culture and Rule

The Muhallabids (771–793 AD) had much freedom in governing Ifriqiya. One governor was al-Aghlab ibn Salim (765–767 AD), an ancestor of the Aghlabids. Muhallabid rule weakened, and a rebellion spread to Kairouan. The Caliph's governor couldn't restore order.

Ibrahim I ibn al-Aghlab, a provincial leader with a disciplined army, brought stability in 797 AD. He then asked the 'Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid to grant him Ifriqiya as a hereditary land, with the title of amir. The caliph agreed in 800 AD. The 'Abbasids received annual tribute, and their authority was mentioned in Friday prayers, but their control was mostly symbolic.

From 800 to 909 AD, Ibrahim ibn-al-Aghlab (800–812 AD) and his family, the Aghlabids, ruled Ifriqiya, as well as parts of Algeria and Tripolitania. They were mostly from the Arab tribe of Bani Tamim. Their army included Arab immigrant warriors, Islamized native people (Afariq), and black slave soldiers. The rulers often relied on their black soldiers.

Despite peace, economic growth, and cultural development, many in the Arabic-speaking elite criticized the Aghlabid government.

First, the Arab military officers were unhappy with the government's legitimacy and often fought among themselves. A dangerous revolt within the Arab army broke out near Tunis from 824 to 826 AD. The Aghlabids were saved only by getting help from the Kharijite Berbers.

Second, Muslim scholars (ulema) disapproved of the Aghlabid rulers' un-Islamic lifestyle. They also criticized Aghlabid taxes that were not allowed by Islamic law. Other opponents criticized their poor treatment of Berbers who had converted to Islam. The Islamic idea of equality, regardless of race, was important to the Sunni movement in the Maghrib.

To make up for this, the Aghlabid rulers built or improved mosques, like the Olive Tree Mosque in Tunis and its famous university, Ez-Zitouna. They also built fortified monasteries (ribats) where Islamic warriors trained.

In 831 AD, Ibrahim's son, Ziyadat Allah I (817–838 AD), launched an invasion of Sicily. The religious judge Asad ibn-al-Furat commanded this jihad. The expedition was successful, and Palermo became the capital of the captured region. Later, raids were made against Italy, and Rome was attacked in 846 AD. By invading Sicily, the Aghlabids united two rebellious groups (the army and the clergy) against outsiders. This helped stabilize the political order in Ifriqiya. In its final decline, the dynasty fell apart due to internal conflicts.

Institutions and Society

In the Aghlabid government, high positions were usually given to "princes of the blood" whose loyalty was trusted. The judicial post of Qadi of Kairouan was given to very conscientious and knowledgeable people. Administrative staff included recent Arab and Persian immigrants, and local bilingual Afariq (mostly Berbers and Christians). The Islamic state in Ifriqiya was similar to the government in Abbasid Baghdad, with a prime minister (vizier), chamberlain (hajib), and many secretaries. Leading Jews formed a small elite group. Most of the population were rural Berbers, who were sometimes distrusted.

Kairouan became the cultural center of Ifriqiya and the entire Maghrib. Among Sunni Muslim scholars, two professions became prominent: the faqih (jurist) and the ābid (ascetic).

The fuqaha gathered in Kairouan, the legal center of al-Maghrib. At first, the more liberal Hanafi school of law was common, but soon a strict form of the Maliki school became dominant. This remains the main school of law in Tunisia and Northwest Africa today. The Maliki school was brought to Ifriqiya by the jurist Asad ibn al-Furat. By choosing the Maliki school, Ifriqiya gained more control over its legal culture. Maliki jurists often disagreed with the Aghlabids, for example, over their personal behavior and taxation. The Maliki fuqaha were also seen as protecting Berber interests and local independence from Arab power from the east.

The most famous ābid scholar was Buhlul b. Rashid (died 799 AD), who was known for his piety and independence. The abid gained social respect and a voice in politics, especially for the cities, criticizing the government's financial decisions.

Ifriqiya prospered under Aghlabid rule. They greatly improved water systems to support olive groves and other agriculture. Roman aqueducts were rebuilt to supply towns with water. Hundreds of basins were built in the Kairouan region to store water for horses.

Trade also resumed under the new Islamic government, especially by sea with the Egyptian port of Alexandria. Trade routes also linked Ifriqiya with the Sahara and Sudan for the first time. Camels became widely used for Saharan trade. Desert cities like Sijilmasa and Wargla became important trading hubs for salt and gold.

A strong economy allowed for luxurious court life and the building of new palace cities like al-'Abbasiya and Raqada for the rulers. The architecture was later copied in other cities.

During the Aghlabid Dynasty (799–909 AD), Ifriqiya generally remained a leading region in the Maghrib due to its peace, stability, cultural achievements, and wealth.

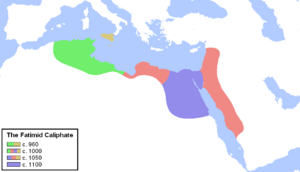

Fatimids: Shi'a Caliphate, and the Zirids

As the Fatimids grew stronger in the west, they frequently attacked the Aghlabid government in Ifriqiya, causing political instability. The Fatimids eventually captured Kairouan in 909 AD, forcing the last Aghlabid ruler to leave. On the east coast of Ifriqiya, facing Egypt, the Fatimids built a new capital called Mahdiya.

Origin of the Fatimids

The Fatimid movement began in al-Maghrib, among the Kotama Berbers in Kabylia (eastern Algeria). However, its two founders were recent immigrants from the Islamic east, both religious dissidents. Abu 'Abdulla ash-Shi'i was from Yemen, and 'Ubaidalla Sa'id was from Syria. 'Ubaidalla Sa'id claimed descent from Fatimah, the daughter of the prophet Muhammad, and declared himself the Fatimid Mahdi. Their religious group was the Ismaili branch of the Shia.

Abu 'Abdulla, the Ismaili propagandist, arrived around 893 AD. He found support among the Kotama Berbers who were hostile to the Caliphate in Baghdad. After gaining followers, Abu 'Abdulla sent for 'Ubaidalla Sa'ed, who arrived in 910 AD, declared himself Mahdi, and took control. Abu 'Abdulla was later killed in a leadership dispute.

From the start, the Mahdi focused on expanding eastward. He attacked Egypt twice, in 914 and 919 AD, quickly taking Alexandria but losing to the Abbasids. The Mahdi also sent an invasion westward, but with mixed results. Many Sunnis, including the Umayyad Caliph of al-Andalus and the Zenata Berber kingdom in Morocco, opposed him because of his Ismaili Shi'a beliefs. The Mahdi did not follow Maliki law and taxed harshly, causing resentment. His capital, Mahdiya, was more a fort than a grand city. The Maghrib was divided between the Zenata and the Sanhaja who supported the Fatimids.

After the Mahdi's death, a Kharijite revolt led by Abu Yazid (nicknamed "the man on a donkey") spread chaos. The Mahdi's son, the Fatimid caliph al-Qa'im, was besieged in Mahdiya. Eventually, Abu Yazid was defeated by the next Fatimid caliph, Ishmail, who then moved his residence to Kairouan. Fatimid rule continued to be challenged by Sunni Islamic states to the west.

In 969 AD, the Fatimid caliph al-Mu'izz sent his general Jawhar al-Rumi with a Kotama Berber army to Egypt. They conquered Egypt easily. The Shi'a Fatimids founded al-Qahira (Cairo) ["the victorious"]. In 970 AD, they also founded the famous al-Azhar mosque. Three years later, al-Mu'izz left Ifriqiya for Egypt, taking all his treasures and staff. From Cairo, the Fatimids expanded their control to Syria and Mecca, while keeping control of Northwest Africa. They never returned to Ifriqiya.

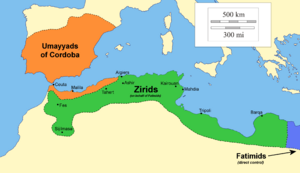

Zirid Succession

After moving their capital to Cairo, the Fatimids gave direct rule of al-Maghrib to a local vassal, Buluggin ibn Ziri, a Sanhaja Berber. After his death, the Fatimid vassalage split into two: the Zirid (972–1148 AD) for Ifriqiya, and the Hammadid (1015–1152 AD) for the western lands (modern Algeria). Public safety was often poor due to political disputes and attacks from Sunni states.

Although the Maghrib remained politically confused, Ifriqiya at first prospered under the Zirids. However, the Saharan trade soon declined due to changing demand and competition from other traders. This decline greatly affected Kairouan, the Zirid state's cultural center. To make up for this, the Zirids encouraged trade in their coastal cities, but they faced tough competition from rising city-states like Genoa and Pisa.

In 1048 AD, for economic and popular reasons, the Zirids broke away from the Shi'a Fatimid rule in Cairo. Instead, the Zirids became Sunni (which most Maghribi Muslims preferred) and declared loyalty to the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad. Many Shi'a were killed in disturbances. The Zirid state seized Fatimid coins. Sunni Maliki jurists were re-established as the main school of law. In response, the Fatimids sent an invasion of nomadic Arabians, the Banu Hilal, who had already migrated into Egypt. These bedouins were encouraged to continue westward into Ifriqiya.

The arriving Bedouins of the Banu Hilal defeated Zirid and Hammadid armies and sacked Kairouan in 1057 AD. Some say that much of the Maghrib's later problems came from the chaos caused by their arrival. In Arab stories, Abu Zayd al-Hilali, the Banu Hilal leader, is a hero. As the Banu Hilal tribes took control of the plains, local settled people had to flee to the mountains. In central and northern Ifriqiya, farming gave way to raising animals. Even after the Zirids fell, the Banu Hilal caused disorder. These new Arab arrivals were a second large Arab migration into Ifriqiya. They sped up the process of Arabization, and Berber languages became less common in rural areas.

Greatly weakened, the Zirids slowly faded, while the regional economy declined, and society became unstable.

Perspectives and Trends

The Fatimids were Shi'a (specifically, Isma'ilis), and their leaders came from the east. Today, most Tunisians are Sunni. The Fatimids initially gained support from some Berber groups. However, once in power, Fatimid rule caused social unrest in Ifriqiya. They imposed high, unusual taxes, leading to the Kharijite revolt. Later, the Fatimids moved to Cairo. Although originally a client of the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Egypt, the Zirids eventually expelled the Fatimids from Ifriqiya. In return, the Fatimids sent the destructive Banu Hilal to Ifriqiya, which led to chaotic conditions and economic decline. The Zirid dynasty is seen as a Berber kingdom, founded by a Sanhaja Berber leader. Also, from the far west, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba long fought against the Shi'a Fatimids.

During the period of Shi'a rule, the Berber people seemed to shift from opposing the Sunni east to accepting its beliefs, though still through their own Maliki law. Also, during the Fatimid era, the cultural leadership within al-Maghrib moved from Ifriqiya to al-Andalus (Spain).

Norman Africa

Chaos in Ifriqiya (Tunisia) made it a target for the Norman kingdom in Sicily. Between 1134 and 1148, the Normans seized Mahdia, Gabes, Sfax, and the island of Jerba.

The Kingdom of Africa was an extension of the Norman state in the former Roman province of Africa (Ifrīqiya). It included Tunisia and parts of Algeria and Libya. Norman rule involved military garrisons in major towns, taxes on the local Muslim population, protection for Christians, and minting coins. Local Muslim leaders largely stayed in power, managing civil government under Norman oversight. Economic ties between Sicily and Africa grew stronger.

The Sicilian conquest of Africa began under Roger II in 1146–48. In 1142/3, Roger II attacked Tripoli. In 1146, he besieged and took it. The city was already weakened by famine and civil war. Tripoli was an important port on the sea route from the Maghreb to Egypt. Some smaller leaders near Tripoli sought Sicilian rule.

In June 1148, Roger sent his admiral George of Antioch against al-Hasan of Mahdia. The Sicilians reached Mahdia on June 22. The emir and his court fled, leaving their treasure. Roger quickly issued a royal protection for all city inhabitants. George "restored both cities... lent money to the merchants; gave alms to the poor; placed the administration of justice in the hands of qadi acceptable to the population." Food was released to encourage refugees to return.

On July 1, the city of Sousse surrendered without a fight. On July 12, Sfax fell after a short resistance. The Africans were treated well. Roger appointed Umar ibn al-Husayn al-Furrīānī to rule Sfax. The Normans' control extended from Tripoli to the borders of Tunis.

Submission of Tunis and Unrest

Roger became involved in a war with Byzantium after 1148, so he couldn't attack Tunis. The Tunisians sent grain to Sicily to avoid an attack, which was seen as tribute. Roger died in 1154 and was succeeded by his son William I, who continued to rule Africa. After Roger's death, some Muslim officials wanted sermons preached against the Almohads in mosques.

Almohads (al-Muwahiddin)

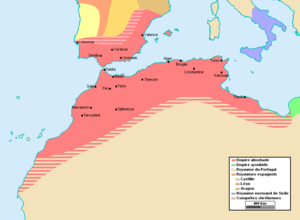

The only strong Muslim power in the Maghreb was the rising Almohads, led by their Berber caliph Abd al-Mu'min. By 1160, they forced the Normans to retreat to Sicily. The Almohads also successfully fought off attacks by the Ayyubids in the 1180s.

Movement and Empire

The Almohad movement [Arabic al-Muwahhidun, "the Unitarians"] ruled in the Maghrib from about 1130 to 1248. This movement was founded by Ibn Tumart (1077–1130), a Masmuda Berber from the Atlas mountains of Morocco, who became the mahdi. After studying and making a pilgrimage to Mecca, he returned to the Maghrib around 1218. He was inspired by the teachings of al-Ash'ari and al-Ghazali. Ibn Tumart was a charismatic leader who preached about the Unity of God. He was a strict reformer who gathered followers among the Berbers and challenged the ruling Almoravids (1056–1147). The Almoravids had been a Berber Islamic movement that had become weak.

After Ibn Tumart's death, Abd al-Mu'min al-Kumi (around 1090–1163) became the Almohad caliph around 1130. He immediately attacked the Almoravids and took Morocco from them by 1147. He then crossed to Spain (al-Andalus) and invaded the Hammadids of Bougie (Algeria) in 1152. His armies intervened in Zirid Ifriqiya, removing the Christian Sicilians by 1160. However, Italian merchants from Genoa and Pisa continued to be present.

"Abd al-Mu'min briefly ruled a unified Northwest African empire—the first and last in its history under local rule." This was the peak of Maghribi political unity. However, by 1184, a revolt by the Banu Ghaniya spread from the Balearic Islands to Ifriqiya (Tunisia), causing problems for the Almohad government for the next 50 years.

Rule of the Maghrib

Ibn Tumart, the Almohad founder, wrote about his religious and political ideas. He claimed that the leader, the mahdi, was infallible. Ibn Tumart created a hierarchy among his followers that lasted long after the Almohad era. This structure was based on loyalty and a formal system of governance that went beyond tribal loyalties. Ibn Tumart trained his own ideologists (talaba) and religious-military officials (huffaz). He aimed to reduce the influence of traditional tribal structures. These preparations made by Ibn Tumart were very organized and helped different tribes work together.

Ibn Tumart also promoted strict Islamic law and morals over unusual Berber customs. At his early base, Ibn Tumart was "the custodian of the faith, the arbiter of moral questions, and the chief judge." However, he did not favor the Maliki school of law because of its strictness and influence in the Almoravid government. In practice, the Maliki school of law survived and eventually became official. Later, in 1230, Caliph Abu al-'Ala Idris al-Ma'mun affirmed the return of the popular Malikite rite.

Muslim philosophers like Ibn Tufayl (died 1185) and Ibn Rushd (Averroës) (1126–1198), who was also a Maliki judge, were known at the Almohad court in Marrakech. The Sufi master theologian Ibn 'Arabi was born in Murcia in 1165. Under the Almohads, architecture flourished, with the Giralda built in Seville and the pointed arch introduced.

The Almohad empire was inspired by Berbers and led by Berber leaders. They gradually changed their original strict goals. Their movement likely deepened the religious awareness of Muslims across the Maghrib. However, it couldn't suppress other traditions, like the popular cult of saints, the Sufis, and the Maliki jurists, which all survived.

The Almohad empire eventually weakened and fell apart. Spain, except for the Muslim Kingdom of Granada, was lost. In Morocco, the Almohads were followed by the Merinids. In Ifriqiya (Tunisia), they were followed by the Hafsids, who claimed to be the true heirs of the Almohads.

Hafsid Dynasty of Tunis

The Hafsid dynasty (1230–1574) took over after Almohad rule in Ifriqiya. The Hafsids claimed to follow the spiritual heritage of the Almohad founder, the Mahdi Ibn Tumart. Under the Hafsids, Tunisia would eventually regain cultural leadership in the Maghrib for a time.

Political History

Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti was one of the "Ten," the first important followers of the Almohad movement around 1121. These "Ten" were companions of Ibn Tumart and advised him on all important matters. Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti was a powerful figure within the Almohad movement for a long time. His son, 'Umar al-Hintati, was appointed governor of Ifriqiya in 1207 and served until 1221. His grandson, Abu Zakariya, was the founder of the Hafsid dynasty.

Abu Zakariya (1203–1249) served the Almohads as governor of Gabès, then as governor of Tunis in 1226. In 1229, during problems within the Almohad movement, Abu Zakariya declared his independence, starting the Hafsid dynasty. In the next few years, he secured control of Ifriqiya's cities, then captured Tripolitania (1234) to the east and Algiers (1235) to the west, later adding Tlemcen (1242). He strengthened his rule among the Berber groups. The Hafsid government was highly centralized, following the Almohad model. Abu Zakariya became the most important ruler in the Maghrib.

For a brief time, Abu Zakariya's son, al-Mustansir (ruled 1249–1277), was recognized as caliph by Mecca and the Islamic world (1259–1261) after the Abbasid caliphate ended in 1258 due to the Mongols. However, this moment passed, and the Hafsids remained a local power.

In 1270, King Louis IX of France landed an army near Tunis, but disease devastated their camp. Later, Hafsid influence was reduced by the rise of the Moroccan Marinids of Fez, who captured and lost Tunis twice (1347 and 1357). However, Hafsid fortunes recovered under notable rulers like Abu Faris (1394–1434) and his grandson Abu 'Amr 'Uthman (1435–1488).

Towards the end, internal problems within the Hafsid dynasty made them vulnerable. A major power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Turks for control of the Mediterranean began. The Hafsid rulers became pawns in these conflicts. By 1574, Ifriqiya was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire.

Trade and Economy

The entire Maghrib, including Tunisia under the early Hafsids, prospered due to increased trade across the Sahara and with the Mediterranean, including Europe. Repeated dealings with Christians led to new practices and agreements that ensured security, customs revenue, and commercial profit. The main customs ports were Tunis, Sfax, Mahdia, Jerba, and Gabés in Tunisia, along with others in Algeria and Libya.

At these ports, imports were unloaded and moved to a customs area. They were stored in a sealed warehouse until duties and fees were paid. The Tunis customs service was a structured bureaucracy. At its head was often a noble, who managed staff, negotiated trade agreements, and acted as a judge in disputes involving foreigners. Duties usually ranged from five to ten percent. A ship could unload and pick up new cargo in a few days. Christian merchants, often organized by their home city, set up their own trading facilities in these North African ports.

Islamic law during this era developed a system to regulate community morals, called hisba. This included keeping public markets orderly, supervising transactions, and related matters. The city official in charge was the muhtasib. The muhtasib ensured fair dealing, honest weights and measures, kept roads open, regulated building safety, and checked the value of coins. The muhtasib's authority was between a judge and the police. They could order punishments, close shops, and expel people from the city. Their authority did not extend to the countryside.

During this period, Muslim and Jewish immigrants from al-Andalus brought valuable skills, like trade connections, crafts, and farming techniques. However, a sharp economic decline began in the 14th century due to various factors. Later, Mediterranean trade shifted towards corsair (pirate) raiding.

Society and Culture

Thanks to early prosperity, al-Mustansir transformed his capital, Tunis, building a palace and a beautiful park. He also created an estate near Bizerte. However, a divide grew between city governance and the countryside. Sometimes, city rulers granted rural tribes autonomy in exchange for their support in conflicts. This tribal independence meant that when the central government weakened, the local areas might remain strong.

Bedouin Arabs continued to arrive into the 13th century. With their ability to raid and fight, they remained influential. The Arabic language became dominant, except for a few Berber-speaking areas like Djerba and the desert south. Also, Arab Muslim and Jewish migration continued from al-Andalus into Ifriqiya, especially after the fall of Granada in 1492. These new immigrants brought the developed arts of al-Andalus.

After a break under the Almohads, the Maliki school of law fully resumed its traditional role in the Maghrib. In the 13th century, the Maliki school became more flexible, partly due to Iraqi influence. Under Hafsid legal experts, the concept of maslahah or "public interest" developed in their law. This allowed Maliki law to consider necessity and circumstances for the community's general welfare. Through this, local customs were included in Islamic law. Later, the Maliki theologian Muhammad ibn 'Arafa (1316–1401) of Tunis studied at the Zaituna library, which was said to have 60,000 books.

Education improved with the establishment of madrasahs (religious schools). Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam, became more established, connecting cities and rural areas. Poetry and architecture also flourished. For a time, Tunisia regained cultural leadership of the Maghrib.

Ibn Khaldun: A Great Thinker

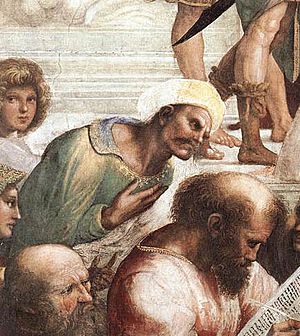

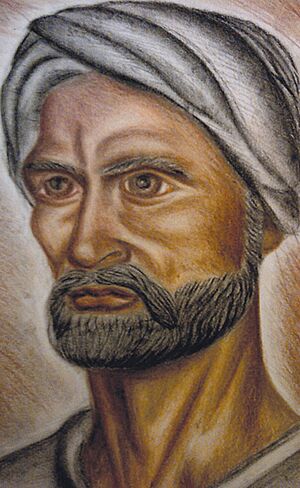

Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) was a major social philosopher, recognized as a pioneer in sociology and history. Although his family had Yemeni roots, they lived in al-Andalus for centuries before moving to Ifriqiya in the 13th century. Born in Tunis, he spent much of his life under the Hafsids, sometimes serving their government.

Ibn Khaldun started his political career early, working for different rulers of small states. He rose to become a prime minister (vizier) but also spent a year in prison. His career required him to move several times, including to Fez, Granada, and eventually Cairo, where he died. He took breaks from politics to write. After his pilgrimage to Mecca, he served as the Grand Qadi (judge) of the Maliki rite in Egypt. While visiting Damascus, Tamerlane captured the city, and Ibn Khaldun met the conqueror.

Ibn Khaldun's historical writings were shaped by his philosophical learning and his experiences in unstable governments. His history tried to explain the repeating patterns of states in the Maghrib: a new ruling group comes to power with strong loyalties, which then weaken over generations, leading to the group's collapse. He called the "social cohesion" needed for a group's rise and rule Asabiyyah.

His seven-volume Kitab al-'Ibar [Book of Examples] is a "universal" history focusing on Persian, Arab, and Berber civilizations. Its long introduction, the Muqaddimah, analyzes long-term political trends as human phenomena, using sociological ideas. It is considered a brilliant cultural analysis.

In the later books of Kitab al-'Ibar, he focuses on the history of the Berbers of the Maghrib. Ibn Khaldun wrote about events he witnessed or experienced himself. As an official of the Hafsids, he saw firsthand the effects of troubled governments and the region's long-term decline.

Ottoman Caliphate and the Beys

In the 16th century, a long struggle for the Mediterranean began between Spain (which completed its reconquista in 1492) and the Ottoman Turks (who captured Constantinople in 1453). Spain then occupied several ports in Northwest Africa, including Oran (1505), Tripoli (1510), and Tunis (1534). Some Muslim rulers encouraged Turkish forces to enter the area to counter the Spanish. However, the Hafsids of Tunis saw the Turks as a greater threat and allied with Spain.

The Ottoman Empire accepted many corsairs (pirates) as their agents, who used Algiers as their base. These included Khair al-Din and his brother Aruj (both known as Barbarossa). In 1551, the corsair Dragut was installed in Tripoli. In 1569, Uluj Ali, advancing from Algiers, seized Tunis. After a Christian naval victory at Lepanto in 1571, Don John of Austria retook Tunis for Spain in 1573. Uluj Ali returned in 1574 with a large fleet and army to finally capture Tunis. He then sent the last Hafsid ruler to Constantinople.

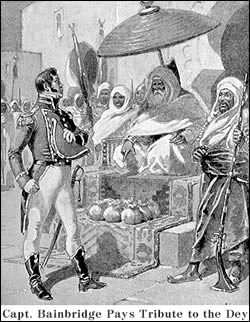

Janissary Deys

After permanent Ottoman rule was established in 1574, Tunisia's government became more stable. The Sublime Porte (Ottoman government) in Constantinople appointed a Pasha as the civil and military ruler in Tunisia, making it an Ottoman province. Turkish became the language of the state. Tunis was initially guarded by 4,000 Janissaries, soldiers recruited mainly from Anatolia. The Pasha in Tunisia later recruited soldiers from various regions. From 1574 to 1591, a council (the Divan), made of senior military officers and local nobles, advised the government.

The new Turkish rule was welcomed in Tunis and by the scholars (ulama). Although the Ottomans preferred the Hanafi school of law, some Tunisian Maliki jurists were allowed into the administration. However, the rule remained that of a foreign elite. In the countryside, Turkish troops controlled the tribes, but their rule was unpopular. The rural economy was not effectively regulated by the central government. For income, the government mainly relied on corsair raiding in the Mediterranean.

In 1591, Janissary junior officers (deys), who were not of Turkish origin, forced the Pasha to recognize the authority of one of their own, called the Dey (elected by his fellow deys). The Dey ruled the cities, relatively independent of the Ottomans. 'Uthman Dey (1598–1610) and Yusuf Dey (1610–1637) brought peace and order.

In tribal rural areas, control and tax collection were given to a chieftain called the Bey (Turkish). Twice a year, armed expeditions patrolled the countryside to show the central government's power. The Beys organized rural cavalry, mostly Arab, recruited from "government" tribes.

Muradid Beys

Murad Curso (died 1631), originally from Corsica, became the Bey and exercised his power effectively. He was later also named Pasha, though his position was still below the Dey. His son Hamuda (1631–1666) inherited both titles with support from Tunis's local nobles. As Pasha, the Bey gained prestige from his connection to the Sultan-Caliph in Constantinople. In 1640, Hamuda Bey managed to control appointments to the Dey's office.

Under Murad II Bey (1666–1675), Hamuda's son, the Diwan again functioned as a council of nobles. However, in 1673, the janissary deys revolted as their power declined. In the fighting, the urban forces of the janissary deys fought against the Muradid Beys, who had mostly rural forces under tribal leaders and popular support from city nobles. As the Beys won, so did the rural Bedouins and Tunisian nobles. The Arabic language returned to local official use, though the Muradids continued to use Turkish in the central government to emphasize their elite status and Ottoman connection.

After Murad II Bey's death, internal family conflicts led to armed struggles. The Turkish rulers of Algeria intervened in these conflicts, which caused civil unrest and Algerian interference. The last Muradid Bey was killed in 1702.

During the Muradid era, there was a gradual economic shift. Corsair raiding decreased due to pressure from Europe, and commercial trade based on agricultural products (mainly grains) increased. However, Mediterranean trade was mostly carried by European ships. To maximize profits from exports, the Beys created government monopolies that controlled trade between local producers and foreign merchants. This meant the rulers and their business partners (elites connected to the Ottomans) took most of Tunisia's trade profits. This prevented the growth of local landowners or wealthy merchants. A social divide remained, with important families in Tunisia seen as a "Turkish" ruling class.

Husaynid Beys

The Husaynid Beys ruled from 1705 to 1881 and reigned until 1957. In theory, Tunisia remained a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, but the Ottomans could not enforce obedience.

Husayn ibn Ali (1669–1740), a cavalry officer of Greek Cretan origin, came to power in 1705. He gained support from Tunisian scholars, nobles, and tribes by opposing Algerian influence. However, a succession dispute led to a civil war between his nephew Ali and his son Muhammad.

Early Husaynid policy balanced several groups: the Ottomans, the Turkish-speaking elite in Tunisia, and local Tunisians (urban and rural, nobles and clerics, landowners and tribes). They avoided too much involvement with the Ottoman Empire but fostered religious ties to the Ottoman Caliphate for prestige. Janissaries were still recruited, but tribal forces were increasingly relied upon. Turkish was spoken at the top, but Arabic use in government increased. Kouloughlis (children of mixed Turkish and Tunisian parents) and native Tunisian nobles were given higher positions. However, the Husaynid Beys did not intermarry with Tunisians, often marrying mamluks instead. The dynasty always identified as Ottoman and privileged. Nonetheless, local scholars were courted with funding for religious education. Maliki jurists entered government service. Tribal leaders were recognized and invited to conferences. A few prominent Turkish-speaking families were especially favored, given business and land opportunities, and important government posts based on their loyalty.

The French Revolution and its aftermath caused economic disruptions in Europe, which allowed Tunisia to profit. Hammouda Pasha (1781–1813) was Bey during this prosperous period. He also repelled an Algerian invasion in 1807 and put down a janissary revolt in 1811.

After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Britain and France made the Bey agree to stop sponsoring corsair raids, which had resumed during the Napoleonic wars. In the 1820s, Tunisia's economy declined sharply. The Tunisian government was particularly affected because of its monopolies on many exports. They borrowed money to cover deficits, but the debt grew to unmanageable levels. Foreign businesses increasingly controlled domestic trade.

Under the French Protectorate (1881–1956), the Husaynid Beys continued in a mostly ceremonial role. After independence, a republic was declared in 1957, and the Beylical office ended.

Era of Reform

In the 19th century, under the Husaynid Beys, trade with Europeans increased. Many foreign merchants established permanent residences. In 1819, the Bey agreed to stop corsair raids. In 1830, the Bey also agreed to enforce treaties between the Ottomans and European powers, which allowed European consuls to act as judges in cases involving their citizens. In 1830, the French army occupied neighboring Algeria.

Ahmad Bey (1837–1855) took the throne during this complex time. Following the examples of the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, he began to modernize Tunisia's armed forces. He started a military school and industries to supply his army and navy. He also began recruiting and conscripting native Tunisians into the military, which helped bridge the gap between the state and its citizens. However, the resulting tax increases were unpopular.

Although he wanted Ottoman support, Ahmad Bey repeatedly refused to apply Ottoman legal reforms regarding citizen rights. Instead, he introduced his own progressive laws, showing Tunisian authority in modernization. The slave trade was abolished in 1841, and slavery in 1846. These reforms had limited application to many Tunisians. Ahmad Bey continued the Beylical policy of avoiding political attachment to the Ottoman state but welcoming religious ties to the Ottoman Caliphate.

To maintain Tunisia's independence, Ahmad Bey sent 4,000 Tunisian troops to fight against the Russian Empire during the Crimean War (1854–1856). By doing so, he allied Tunisia with the Ottoman Empire, France, and Great Britain.

Modernity and the French Protectorate

As the 19th century began, Tunisia remained semi-independent, though officially an Ottoman province. Trade with Europe grew dramatically, with Western merchants setting up businesses. In 1861, Tunisia enacted the first constitution in the Arab world. However, a move towards a modern republic was hindered by a poor economy and political unrest. Loans from foreigners to the government became difficult to manage. In 1869, Tunisia declared bankruptcy. An international financial commission, with representatives from France, the United Kingdom, and Italy, took control of the economy.

Initially, Italy wanted Tunisia as a colony the most, due to investments, citizens, and geographic closeness. However, Britain and France worked together to prevent this, with Britain supporting French influence in Tunisia in exchange for control over Cyprus. France still faced Italian influence and decided to find an excuse for a preemptive strike. In spring 1881, the French army occupied Tunisia, claiming Tunisian troops had crossed the border into Algeria. Italy protested but did not risk a war with France. On May 12, 1881, Tunisia officially became a French protectorate with the signing of the treaty of Bardo by Muhammad III as-Sadiq. This gave France control over Tunisian governance.

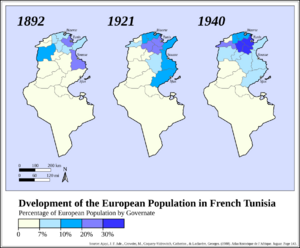

The French gradually took over more important administrative positions. By 1884, they supervised all Tunisian government departments dealing with finance, education, public works, and agriculture. They guaranteed Tunisia's debt and then abolished the international finance commission. French settlements in the country were encouraged. The number of French colonists grew from 34,000 in 1906 to 144,000 in 1945, occupying about one-fifth of the cultivated land. Roads, ports, railroads, and mines were developed. In rural areas, the French administration strengthened local officials and weakened independent tribes. A separate judicial system was set up for Europeans, without interfering with existing Islamic courts for Tunisians.

Many welcomed the changes but preferred to manage their own affairs. Kayr al-Din had introduced modernizing reforms before the French occupation. Some of his companions later founded the magazine al-Hadira in 1888. Other publications challenged French rule. Political parties emerged, some with pro-Ottoman leanings. Disputes over a Muslim cemetery led to large demonstrations and violence in late 1911. Further protests in 1912 led to the closing of nationalist newspapers and the exile of nationalist leaders.

Organized nationalist feelings, forced underground in 1912, reappeared after World War I. The formation of the League of Nations in 1919 encouraged them. Nationalists established the Destour (Constitution) Party in 1920. Habib Bourguiba founded and led its successor, the Neo-Destour Party, in 1934. French authorities later banned this new party.

During World War II, French authorities in Tunisia supported the Vichy government. After initial victories, German General Erwin Rommel lost the decisive battle of al-Alamein in Egypt in 1942. After Allied landings in the west (Operation Torch), the Axis army retreated to Tunisia and set up defenses. The fighting ended in May 1943, with the German Afrika Corps surrendering.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower stated that the goal was to gradually widen the government's base, with the final aim of giving all internal affairs to popular control. Tunisia became a staging area for the invasion of Sicily later that year.

After World War II, the struggle for national independence continued and intensified. The Neo-Destour Party reemerged under Habib Bourguiba. However, with a lack of progress, violent resistance to French rule began in the mountains in 1954. Tunisians coordinated with independence movements in Algeria and Morocco. Ultimately, the Neo-Destour Party gained sovereignty for its people through skillful negotiation.

Tunisian Republic

Independence from France was achieved on March 20, 1956. The state was established as a constitutional monarchy with the Bey of Tunis, Muhammad VIII al-Amin Bey, as the king of Tunisia.

The Era of Habib Bourguiba

In 1957, Prime Minister Habib Bourguiba abolished the monarchy and firmly established his Neo Destour (New Constitution) party. The government aimed for a well-structured system with efficient state operations, but not democratic-style politics. The bey (a quasi-monarchist institution from Ottoman rule) was also ended. Bourguiba then dominated the country for 31 years, leading with thoughtful programs that brought stability and economic progress. He suppressed Islamic fundamentalism and established rights for women unmatched by other Arab nations. Bourguiba's vision was a Tunisian republic with a secular, populist, and modern political culture. He aimed for a unique future combining tradition and innovation, Islam with liberal prosperity.

"Bourguibism" was also strongly non-militarist. Bourguiba argued that Tunisia could never be a strong military power, and building a large military would only use up valuable resources and potentially lead to military involvement in politics, as seen in other Middle Eastern countries. For economic development, Bourguiba nationalized religious land holdings and dismantled some religious institutions.

Bourguiba's great strength was that "Tunisia had a mature nationalist organization, the Neo Destour Party, which at independence had the nation's trust." It had gained support from city workers and rural people. Its leaders were respected and developed reasonable government programs.

In July 1961, Tunisia imposed a blockade on the French naval base at Bizerte to force its evacuation. The crisis led to a three-day battle, resulting in many deaths. France eventually gave the city and naval base to Tunisia in 1963.

One serious rival to Habib Bourguiba was Salah Ben Yusuf. He had absorbed pan-Arab nationalism while exiled in Cairo in the early 1950s. However, due to his strong opposition to the Neo Destour leadership's negotiations with France, Ben Youssef was removed from his position and expelled from the party. He rallied unhappy union members, students, and others. He eventually left Tunisia for Cairo.

Socialism was not initially a main part of the Neo Destour plan, but the government always had policies to redistribute wealth. A large public works program started in 1961. In 1964, Tunisia entered a short-lived socialist era. The Neo Destour party became the Socialist Destour, and a state-led plan for agricultural cooperatives and public industry was created. This socialist experiment faced much opposition within Bourguiba's coalition. Ahmed Ben Salah, the planning minister, was dismissed in 1970. Many socialized operations were returned to private ownership in the early 1970s. In 1978, a general strike was put down by the government, killing dozens, and union leaders were jailed.

After independence, Tunisia's economic policy focused on light industry, tourism, and developing its phosphate deposits. Agriculture, with small farms, remained a major sector but did not produce well. In the early 1960s, the economy slowed down, and the socialist program did not fix it.

In the 1970s, Tunisia's economy grew very well. Oil was discovered, and tourism continued to thrive. City and countryside populations became roughly equal. However, agricultural problems and urban unemployment led to more migration to Europe.

The Era of Ben Ali

In the 1980s, the economy performed poorly. In 1983, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forced the government to raise the price of bread, causing severe hardship and riots. In this situation, the Islamic Tendency Movement (MTI) under Rached Ghannouchi gained popular support. Civil disturbances were suppressed by government security forces under General Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The government continued its program, and Ben Ali was named prime minister.

The 84-year-old President Bourguiba was overthrown and replaced by Ben Ali, his Prime Minister, on November 7, 1987. The new president changed little in Bourguiba's political system, except renaming the party the Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD).

In 1988, Ben Ali tried a new approach to government and Islam by reaffirming the country's Islamic identity. Several Islamist activists were released from prison. He also formed a national pact with the Islamic Tendency Movement, which later changed its name to an-Nahda (the Renaissance Party). But Ben Ali's new approach did not work out. An-Nahda claimed to have done well in the 1989 elections, which seemed unfair, with pro-government votes often over 90%. Ben Ali then banned Islamist political parties and jailed many activists.

In 2004, Ben Ali was re-elected President for a five-year term with a reported 94.5% of the vote. Also elected were 189 members of the Chamber of Deputies for a five-year term. There was also a Chamber of Advisors with 126 members serving six-year terms. The court system combined French Civil Law and Islamic Sharia Law.

A widely supported human rights movement emerged, including Islamists, trade unionists, lawyers, and journalists. However, Tunisia's political institutions remained authoritarian. As of 2001, the government's response to calls for reform included house arrests and imprisonment. The government continued to refuse to recognize Muslim opposition parties and ruled the country with strict political control, sometimes using military and police force to suppress dissent.

In foreign affairs, Tunisia maintained close ties to the West while generally following a moderate, non-aligned stance. The Arab League was headquartered in Tunis from 1979 to 1991.

Tunisia in the 2000s

Tunis, the capital, has about 700,000 people, and Sfax, the second city, has about 250,000. The birth rate has fallen from 7 children per woman in the 1960s to 2 in 2007. Life expectancy is 75 for females and 72 for males. The population is 98% Muslim, 1% Christian, and 1% Jewish and other. Education is required for eight years. The official language is Arabic, with French also spoken, especially in business. Less than 2% speak Berber. Literacy for those over 15 is 74% overall, 83% for males, and 65% for females. In 2006, 7.3 million mobile phones were in use, and 1.3 million people were on the internet. There were 26 television stations and 29 radio stations. Over half the population lives in urban areas, with about 30% working in agriculture. Unemployment was about 15.6% in 2000 and 13.9% in 2006. Over 300,000 Tunisians were reported to be living in France in 1994. Many rural and urban poor, including small businesses, did not benefit from the recent prosperity.

The currency is the dinar, which was about 1.33 per U.S. dollar in 2006, with inflation estimated at 4.5%. Tunisia's per capita annual income was about 8,900 U.S. dollars in 2006. Between 1988 and 1998, the economy more than doubled. The economy grew at 5% per year during the 1990s (the best in Northwest Africa) but hit a 15-year low of 1.9% in 2002 (due to drought and a decline in tourism). It regained a 5% rate for 2003–2005 and was 4%–5% for 2006. Tunisia's economy is diverse. Its products are mainly from light industry (food processing, textiles, footwear, mining, construction materials) and agriculture (olives, grains, tomatoes, citrus, dates, almonds, vegetables, grapes, beef, dairy). Other production comes from petroleum and mining (phosphates, iron, oil, lead, zinc, salt). Tunisia is self-sufficient in oil but not natural gas. A significant part of the economy comes from tourism. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was about 12.5% agriculture, 33.1% industry, and 54.4% services. Exports went to France (29%), Italy (20%), Germany (9%), Spain (6%), Libya (5%), and the U.S.A. (4%). Imports came from France (25%), Italy (22%), Germany (10%), and Spain (5%). An agreement with the European Union aimed for full free trade by 2008.

The countryside changes from north to south. In the north and central coast, orchards and fields are common. In the central plains, there is more pasture. Overall, arable land is 17%–19%, with forests and woodlands at 4%, permanent crops at 13%, and irrigated lands at 2.4%. About 20% is used for pasture. Fresh water resources are limited. In the south, the environment becomes increasingly dry, leading to the Sahara desert. Roads total about 20,000 km, with two-thirds paved. Most unpaved roads are in the desert south.

The "Dignity Revolution"

The Ben Ali government ended after nationwide protests. These protests were caused by high unemployment, rising food prices, corruption, a lack of political freedoms like freedom of speech, and poor living conditions. The protests were the most significant social and political unrest in Tunisia in 30 years. Many people died or were injured, mostly due to actions by police and security forces. The protests led to President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali being forced out of power 28 days later, on January 14, 2011. He officially resigned after fleeing to Saudi Arabia, ending his 23 years in power. In Western media, these events were often called the Jasmine Revolution, but in Tunisia, it is generally known as the Dignity Revolution (ثورة الكرامة).

After Ben Ali was overthrown, Tunisians elected a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution. An interim government, called the Troika, was formed. It was a coalition of three parties: the Islamist Ennahda Movement, the center-left Congress for the Republic, and the left-leaning Ettakatol. However, widespread discontent remained, leading to the 2013–14 Tunisian political crisis. Thanks to the efforts of the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, the Constituent Assembly finished its work. The interim government resigned, and new elections were held in 2014, completing the transition to a democratic state. The Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet was awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for its important role in building a democracy in Tunisia after the 2011 revolution.

Presidency of Kais Saied

Tunisia's first democratically elected president, Beji Caid Essebsi, died in July 2019. After him, Kais Saied became Tunisia's president after a big victory in the 2019 Tunisian presidential election in October 2019. On October 23, 2019, Kais Saied was sworn in as president.

On July 25, 2021, following violent demonstrations against the government and a growing COVID-19 outbreak, Saied suspended parliament for 30 days. He also removed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi from his duties, took away the immunity of parliament members, and ordered the military to close the parliament building. Critics saw Saied's actions as signs of a coup, as they seemed to disregard Article 80 of the Tunisian constitution, which requires the president to consult the prime minister and parliament head before declaring an emergency, and even then, parliament cannot be suspended.

In September 2021, President Kaïs Saïed announced plans to reform the 2014 Constitution and form a new government led by Najla Bouden Romdhane, who became Tunisia's and the Arab world's first woman prime minister. A constitutional referendum was scheduled for July 25, 2022. After the referendum results showed that 90% of voters supported Saied, he declared victory and promised that Tunisia would enter a new phase with his increased power. Critics worried that the new constitution risked bringing back authoritarian rule to the country.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Túnez para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Túnez para niños

- Berber people

- Berber languages

- Phoenician languages

- Phoenicia

- Carthage

- History of the Jews in Tunisia

- North Africa during the Classical Period

- Umayyad conquest of North Africa

- Ifriqiya

- Aghlabid Dynasty

- Almohad

- Hafsid

- Barbary Coast

- List of Beys of Tunis

- French occupation of Tunisia

- History of French-era Tunisia

- Tunisian naturalization issue

- Thala-Kasserine Disturbances

- Timeline of Tunisia

- Tunisian Italians

- Tunisia

- History of modern Tunisia

- Tunis history and timeline (capital and largest city)

- History of Africa

- Tunisian Campaign

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |