History of Tunisia under French rule facts for kids

The history of Tunisia under French rule began in 1881. This was when France set up a protectorate in Tunisia. It ended in 1956 when Tunisia became independent.

France had already taken over nearby Algeria five decades earlier. Both Tunisia and Algeria had been linked to the Ottoman Empire for about 300 years. But they had also been mostly self-governing for a long time.

Before France arrived, the Bey (ruler) of Tunisia started some modern changes. However, the country faced big money problems and went into debt. A group of European countries then took control of Tunisia's finances. After France took over, it managed Tunisia's international money matters.

The French made many big improvements. These included transport (like roads and railways), factories, banking, public health, and education. Even though these changes were good, French businesses and people were often favored over Tunisians.

Tunisians soon began to express their national pride. They did this through talking and writing. Later, political groups formed. The movement for independence started even before World War I. It grew stronger despite French opposition. Finally, Tunisia became independent in 1956.

Contents

Tunisia's Early Reforms and Debt Problems

At the start of the 1800s, the Husaynid family ruled Tunisia. The Bey was the hereditary (passed down in the family) ruler. Tunisia had been largely self-governing since the early 1700s. It was still 'officially' part of the Ottoman Empire, but only in name.

After the Napoleonic wars, trade with Europe grew a lot. European merchants, especially from Italy, came to Tunisia to start businesses. Many Italian farmers and workers also moved there. As contacts with Europe increased, so did foreign influence.

Under Ahmad Bey (who ruled from 1837 to 1855), many modern reforms began. Later, in 1861, Tunisia created the first constitution in the Arab world. But these efforts to modernize the country faced challenges. Reformers were frustrated by people who liked things the old way. There was also political disorganization and poverty in the countryside. A revolt in 1864 was put down harshly.

Later, Khair al-Din (Khaïreddine), a leading reformer, became chief minister from 1873 to 1877. But he also faced defeat from clever conservative politicians.

European banks loaned money to the Bey's government. This money was for modern projects like improving cities, the military, and public works. But some money was also for the Bey's personal use. These loans often had bad interest rates and terms. It became harder and harder to pay back this foreign debt. In 1869, Tunisia declared itself bankrupt.

An International Financial Commission was then created. Representatives from France, Italy, and Britain led this commission. This group then took control of Tunisia's economy.

French Rule Begins

How France Took Control

At first, Italy was the European country most interested in Tunisia. This was because many Italians already lived there. Also, Italy was geographically very close. But the newly unified Italian state (formed in 1861) wasn't ready to make Tunisia a direct colony.

France, which ruled neighboring Algeria, was also interested. So was Britain, which had the small island of Malta nearby. Britain didn't want one country to control both sides of the Strait of Sicily. From 1871 to 1878, France and Britain worked together to limit Italy's influence. But often, these two countries were rivals.

In 1878, the Congress of Berlin was held. It discussed the weakening Ottoman Empire after its defeat by Russia. At this meeting, Britain, Germany, and France secretly agreed that France could take over Tunisia. Italy was not told about this agreement. France's Foreign Minister, William Waddington, talked a lot with Britain's Lord Salisbury. Otto von Bismarck of Germany, who was against it at first, later saw Tunisia as a way to distract France from Europe. Italy was promised Tarabulus (in what is now Libya). Britain supported France in Tunisia. In return, Britain got its own protectorate over Cyprus (which it bought from the Ottomans). France also agreed to help Britain with a revolt in Egypt.

Meanwhile, an Italian company bought the Tunis-Goletta-Marsa rail line. But France worked to get around this and other issues caused by the large number of Tunisian Italians. France tried to negotiate directly with the Bey to enter Tunisia, but it failed. France then waited for a reason to invade. Italians called this invasion the Schiaffo di Tunisi (Slap of Tunis).

In northwest Tunisia, the Khroumir tribe sometimes raided nearby areas. In spring 1881, they raided across the border into French Algeria. France used this as an excuse to invade Tunisia. They sent an army of about 36,000 soldiers. They quickly advanced to Tunis.

The Bey was soon forced to agree to France's terms. These terms were written in a series of treaties. These documents said that the Bey would remain the head of state. But France would control most of Tunisia's government through the Protectorat français en Tunisie.

Italy protested, but it didn't risk a fight with France. So, Tunisia officially became a French protectorate on May 12, 1881. The ruler, Sadik Bey (1859–1882), signed the Treaty of Bardo at his palace. Later, in 1883, his younger brother and successor, 'Ali Bey, signed the Conventions of La Marsa. Some local groups in the south, encouraged by the Ottomans, resisted for another six months. There was still some instability for several years.

Paul Cambon, the first French Resident-Minister (later called Resident-General), arrived in early 1882. He became the Bey's foreign minister. The French army commander became the minister of war. Soon, another Frenchman became the director-general of finance. Sadik Bey died within a few months. Cambon wanted to show that the Ottoman Empire no longer had any claim over Tunisia. The Ottomans had already agreed to this. So, Cambon arranged the ceremony for 'Ali Bey (1882–1902) to become the new ruler. Cambon personally went with him to the Bardo Palace. There, Cambon officially made him the new Bey in the name of France.

The French gradually took over more important government jobs. By 1884, they managed or oversaw Tunisian government offices. These included finance, post, education, telegraph, public works, and agriculture. The Protectorate then guaranteed Tunisia's state debt (mostly to European investors). After that, they ended the international finance commission.

French people were encouraged to settle in Tunisia. The number of French colonists grew from 10,000 in 1891 to 46,000 in 1911. By 1945, there were 144,000 French settlers.

Economic Growth and Changes

The transportation system was improved. New railroads and highways were built, along with sea ports. By 1884, the Compagnie du Bône-Guelma had already built a rail line. It ran from Tunis west 1,600 km to Algiers. It passed through the fertile Medjerda river valley. Eventually, rail lines were built along the coast. They went from Tabarka to Bizerte, to Tunis and Sousse, to Sfax and Gabès. Inland routes went from coastal ports to Gafsa, Kasserine, and El Kef. Highways were also constructed.

French mining companies explored the land for resources. They invested in various projects. Railroads and ports often helped these mining operations. phosphates (used as fertilizer) were the most important resource found. They were mined near the south-central city of Gafsa. One company got the right to develop the mines and build the railroad. Another built the port facilities at Sfax. The Compagnie des Phosphates et Chemins de Fer de Gafsa became the biggest employer and taxpayer in the Protectorate. Iron and other minerals like zinc, lead, and copper were also mined for the first time during French rule.

Tunisian nationalists complained that these improvements mostly helped France. The French benefited the most. Jobs were more open to French settlers than to Tunisians. French companies brought their own engineers, managers, and skilled workers. These were the highest-paying jobs in Tunisia.

Another major complaint was the 'flood' of cheap manufactured goods. This competition hurt the local artisan class. These skilled workers made goods by hand using traditional methods. They could not compete with the lower prices of French factory-made goods.

The French Protectorate also improved social infrastructure. This included building schools (see below, Education reform) and public buildings. City improvements included new sources of clean water and public sanitation in Tunis and other large cities. Hospitals were built, and the number of medical doctors increased. vaccinations became common, which reduced deaths from epidemics. As a result, the Tunisian population grew steadily. The number of Muslims nearly doubled between 1881 and 1946.

In agriculture, French settlers and companies bought a lot of farmland. This caused anger among Tunisians. Land held in religious trust (Habis or wafq) and tribal lands were made available for purchase. This was due to changes in land laws by the Protectorate. Farming improved, especially the production of olive groves and vineyards.

In rural areas, the French administration strengthened local officials (qa'ids). They also weakened the independent tribes. A new court system was set up for Europeans across the country. It did not interfere with the existing Sharia courts, which continued to handle legal matters for Tunisians.

Education Changes

Despite its problems, the French presence gave Tunisians chances to learn about European advances. Modernizing projects were already a goal of reforms started by the Beys before the French arrived. Tunisians wanted to learn about agriculture, mining, city sanitation, business, banking, government, manufacturing, and education.

Before the Protectorate, most Tunisian schools were religious. Many local kuttab schools focused on memorizing the Qur'an. These schools were usually near mosques and run by the imam. Students could go on to advanced religious schools. The most important was the theological facility at the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan, founded around 670. In the 9th-11th centuries, it taught medicine, botany, astronomy, and math, in addition to religious subjects. It was a center for the Maliki school of law. Muslim scholars from all over North Africa came to study there.

Some educational modernization happened before the French. The Zitouna Mosque school in Tunis, which took the best kuttab graduates, started adding more non-religious topics. Also, the reforming prime minister Khair al-Din founded Sadiki College in Tunis in 1875. This secondary school (lycée) taught a modern curriculum from the start. Instruction was in Arabic and several European languages. Jews also had their own schools, as did the more recently arrived Italians.

During the French Protectorate, Tunisian educators wanted to add more modern subjects. These were subjects that led to useful skills practiced in Europe. French technical words became common in Tunisia for various projects. The French language was favored in new schools set up by the French Church. These schools were mainly for children of French settlers. An example is Collège Saint-Charles de Tunis, founded in 1875.

Many urban Tunisians also wanted their children to learn modern skills for jobs. Tunisian leaders struggled against the Protectorate's resistance to this. Over time, a new education system was created. It included French language instruction open to Tunisians. This happened within the Protectorate's political system. It affected existing Muslim schools, Tunisian progress, and the education of young French settlers.

Changes in education raised sensitive social issues in Tunisia. But many of these issues were not new to the French. Their own education system had changed a lot in the 19th century. As France developed new technologies, French schooling adapted. It also became open to examination. The balance between teaching traditional morals and modern skills was debated. This debate was part of a larger French discussion between religious and secular values. Similar issues later arose in Tunisia, including the views of the national movement.

In 1883, the French set up a Direction de l'Enseignement Public (Directorate of Public Education) in Tunisia. Its goal was to promote schools for French children and spread the French language. Its goals later expanded to include education in general. This Directorate eventually managed all the different education systems in Tunisia. It tried to modernize, coordinate, and expand them. New mixed schools like Collège Alaoui were soon established in Tunis. For women, new schools like École Rue du Pacha and École Louise René Millet were opened.

Several separate education systems developed under the Protectorate. One system served French colons and Tunisians. It was closely linked to France and used the French language. Students from here could attend a university in France. The government also ran a modern secular system using both French and Arabic. The kuttab primary schools remained. They kept their religious instruction but added arithmetic, history, French, and hygiene. Taught mainly in Arabic, the kuttab received government support.

Zitouna Mosque students could come from either the mixed secular or the kuttab religious schools. Zitouna education continued to grow. It ran four-year secondary schools in Tunis, Sfax, and Gabes. It also had a university-level program, while remaining a traditional Islamic institution. Sadiki College became the top lycée in the country. It offered a modern, French-language program to a rising Tunisian elite. These reforms prepared the way for further advances in Tunisian education after independence.

French Background and Politics

France was used to ruling foreign lands. It had two main periods of expansion outside Europe. The first was from the 16th to 18th centuries in North America and India. These lands were lost before the French Revolution. The second was in the 19th and 20th centuries in Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

The later expansion began when the French captured Algiers in 1830. In 1881, Jules Ferry (1832–1893), the French premier, got political agreement to send the French army to conquer Tunisia. During the Protectorate, changes in French politics could directly affect Tunisia. For example, the 1936 election of Léon Blum and the Front Populaire reportedly improved French understanding of Tunisian hopes.

In the 1920s, Habib Bourguiba studied law at the University of Paris. He closely watched how French politicians worked. Bourguiba's political ideas were shaped by his time in Paris. He later became the leader of Tunisia's independence and its first President.

Tunisian Politics and Identity

The French Protectorate brought many Europeans to live in Tunisia. Compared to the Ottomans, who settled tens of thousands, the French and Italians settled hundreds of thousands. This large European presence had a big impact on Tunisia.

Islamic Influences

Most Tunisians understand references to the Muslim world. This is for spiritual ideas, literature, and history. Islam has three main cultural areas: Arab, Iranian, and Turkish. Each influenced Islam and Tunisia.

Before the French, the Ottoman Turks had some control over Tunisia. The ruling class in Tunisia once spoke Turkish. Under the Beys, who were Arabizing rulers, reforms were attempted. These reforms were based on similar changes in the Ottoman Empire.

Arab culture strongly influenced Tunisia since the 8th century. Tunisia became an Arabic-speaking, Muslim country connected to the Arab east. For centuries, Muslim Arab civilization led the world in culture and prosperity. But around 1500, European Christians "caught up with and overtook Islam."

Still, Arabs were respected as creators of ancient civilizations and Islamic civilization. Despite this, Arabs in recent times sought renewal. In the 19th century, a great revival began among Arabs and Muslims. This led to reformers who shared political and ideological messages.

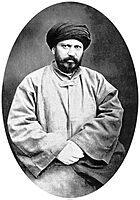

Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) traveled widely. He tried to unite the Muslim world and push for internal reform. In Paris in 1884, al-Afghani published a journal to spread his message. He wanted a government position to start reforms. He taught that Muslims should adopt universal reason under Islamic principles. This would help them reform society and master European sciences. This modernizing didn't convince all traditional scholars, but it energized many Muslims to support reforms. Tunisian nationalists often welcomed these ideas.

Another influential reformer in Tunisia was the Egyptian Shaykh Muhammad 'Abduh (1849–1905). He was a follower of al-Afghani. 'Abduh was a gifted teacher and became the Mufti of Egypt. He believed that in Muslim law, scholars could make original interpretations of sacred texts. 'Abduh visited Tunisia twice. Al-Afghani and 'Abduh are called "the two founders of Islamic modernism."

In Tunisia, Khair al-Din al-Tunsi (1810–1889) was an early reformer. He was of Circassian origin and learned Turkish. He served several Beys in Tunisia (1840s-1877) and learned Arabic. Khair al-Din advocated modern rationalism in government and society. But he also respected Muslim institutions. When he had power to implement reforms (1873–1877), he faced strong opposition and was replaced.

Later, the Tunisian Shaykh Mahammad al-Sanusi led a group that followed al-Afghani and 'Abduh's ideas. In 1885, 60 important people, including al-Sanusi, formally protested the French tax and tariff measures. This protest involved public demonstrations. It showed an "alliance between mosque and bazaar." But the protest was not effective. The French banished al-Sanusi, but he was later reinstated. For the first two decades, Tunisians were "content to pursue Tunisian development within the Protectorate framework."

Some people also had ethnic views, like pan-Arab and pan-Turkic ideas. Many Arabic-speaking countries under Ottoman rule wanted self-rule. But Tunisia was different. It was Arabic-speaking but already free from direct Ottoman control. Tunisia didn't fight against the Turkish empire.

However, in 1881, Tunisia fell under European rule. So did Egypt (1882), Morocco and Libya (1912), and Syria and Iraq (1919). In the early 20th century, the Tunisian resistance movement against France began. It drew on two sources of Islamic political culture: the Ottomans (later Turkey) and the Arab world (Mashriq and Egypt).

The Start of Tunisian Nationalism

The Bey of Tunis was the traditional ruler. Under the Protectorate, the Bey officially continued to rule. But the French Resident General and his ministers, appointed in Paris, had real control. The Bey remained a figurehead. His position had been damaged by the court's "prodigality and corruption." The harsh suppression of the 1864 revolt was still remembered. In the first decade, important Tunisians appealed to Ali Bey to talk with the French. But his power was limited. "In Tunisia, obedience to the Bey meant submission to the French." Yet the Bey did try to keep some Tunisian culture alive.

Many Tunisians at first welcomed the changes brought by the French. But most Tunisians eventually wanted to manage their own affairs. Before the French conquest, in the 1860s and 1870s, Khair al-Din had introduced modernizing reforms. His ideas respected Islamic tradition but also acknowledged Europe's rise. He wrote an important book.

The Arabic weekly magazine al-Hādira [the Capital] was founded in 1888. It was started by followers of Khair al-Din. The weekly discussed politics, history, economics, and the world. It was published until 1910. This moderate magazine spoke to merchants and religious scholars. It shared ideas from Khair al-Din's 1867 book about Islam facing the modern world. The reformers who started the weekly were influenced by the Egyptian Muhammad 'Abduh. Many editorials in al-Hadirah were written by as-Sanusi.

A radical weekly, az-Zuhrah, openly criticized French policy. It ran from 1890 until it was stopped in 1897. Another periodical, Sabil al-Rashad, was also stopped by French authorities (1895–1897). It was published by 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Tha'alibi, who studied at Zaytuna. The young Tha'alibi was inspired by 'Abduh of Cairo.

In 1896, Bashir Sfar and others from al-Hādira founded al-Jam'iyah Khalduniya [the Khaldun Society]. It was approved by the French. The society was named after the famous medieval historian Ibn Khaldun. It provided a place for discussions. It "emphasized the need for gradual reform" of education and family. Khalduniya also helped progressive religious scholars at Zitouna Mosque. It "opened a window on the West for Arabic-speaking Tunisians." It offered free classes in European sciences. Many years later, Khalduniya (and Sadiki College) "channeled many young men, and a few women, into the party" (Neo-Destour). It also helped create demand for foreign Arabic newspapers.

Other Tunisian periodicals continued to appear. Ali Bach Hamba founded the French language journal le Tunisien in 1907. It aimed to inform Europeans about Tunisian views. Its opinions seemed to increase unrest. In 1909, Tha'alibi founded its Arabic language version at Tūnisī. It challenged Hanba's pro-Ottoman views from a more 'Tunisian' perspective. Tha'alibi (1876-1944) was seen as having "strange attire, tendencies, thought and pen." His reform ideas seemed like "an attack on Islam" to "conservative leaders." In 1903, ath-Tha'alibi was "brought to trial as a renegade" and "sentenced to two months imprisonment."

As French rule continued, it seemed to favor French and Europeans over Tunisians. So, the Tunisian response became more determined. Professor Kenneth Perkins notes the "transition from advocacy of social change to engagement in political activism." In 1911, Zaytuni university students caused civil disturbances. This led to Bach Hamba and Tha'alibi agreeing to work together. A political party, al-Ittihad al-Islami, was started. It showed pan-Islamic leanings.

In late 1911, issues about a Muslim cemetery, the Jellaz, caused large nationalist protests in Tunis. The protests and riots resulted in dozens of deaths. The French declared martial law and blamed political agitators. In 1912, more protests led to the popular Tunis Tram Boycott. In response, French authorities closed nationalist newspapers. They also sent Tunisian leaders like Tha'alibi and Bach Hamba into exile. Tha'alibi later returned to Tunisia.

According to professor Nicola Ziadeh, "the period between 1906 and 1910 saw a definite crystallization of the national movement in Tunisia. This crystallization centered around Islam." By World War I (1914–1918), Tunisian 'nationalists' had developed. They had a chance to define themselves, not just locally but also in light of global events. Pan-Islam was promoted by the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid. These ideas also developed in Egypt and India, and reached Tunisia. More conservative opponents of the Protectorate felt its influence strongly. Then in 1909, this sultan was removed. In 1924, the Caliphate in Turkey was ended by Mustafa Kemal.

The intellectuals, business people, students, and workers reacted against French policies. They defended their right to work against immigrants. They demanded equal legal rights with foreigners. They wanted to keep the idea of Tunisian self-rule.

The early political party al-Ittihad al-Islami became "The Evolutionist Party of Young Tunisians." Eventually, it was simply called Tunis al-fatat [Young Tunisians]. But losing its leaders in 1912 reduced its effectiveness. After World War I, Tunis al-fatat became a general term for various Tunisian political and cultural views. In the 1920s, its most important part emerged: a new political party called Destour [Constitution]. The Destour "aimed to restore the Constitution of 1861."

French Settlers' Views

When the French army took over Tunisia, few Europeans lived there. Most were from Italy. In 1884, there were 19,000 Europeans, mostly Italians.

By 1901, there were 111,000 Europeans. This included 72,600 Italians, 24,200 French, and 12,000 Maltese (who spoke Maltese and were from the nearby British colony). The French government soon tried to increase the French population. They offered various benefits, mostly economic, to citizens who moved to Tunisia. Since France had a higher standard of living, these benefits had to be very good compared to Tunisian incomes.

Although always relatively small (peaking at about 250,000), French settlers or colons became very influential in Tunisia. They had business skills and government privileges. Not all French were rich, but they had strong group unity. French money was invested in mining and railroads, which brought good profits. Modern technology needed skilled workers, and French immigrants were usually hired for these jobs. These skilled jobs were among the highest paid in Tunisia. Settler homes and neighborhoods often followed French styles. The French community felt proud of the country's modern development. Some settlers saw Tunisians as narrow-minded or primitive. Settlers formed groups to protect their leading position and their money-making activities.

Tunisians were unhappy about being second-class citizens in their own country. The French tried to win Tunisian favor by showing their ability to modernize the economy. But Tunisians wanted to share in the work and rewards of the new French businesses. Some French administrators realized they needed to include Tunisians in development plans. However, other French administrators preferred to give business and job opportunities to French settlers.

French settlers usually used their influence to get the main benefits from any new economic project. For many French, these benefits were the reason they lived in Tunisia. If a local French administrator decided against them, they would appeal to their political contacts in Paris. They carefully built these connections, for example, through the powerful Parti-Colonial. A conflict naturally grew between the interests of the settlers and Tunisians. This struggle became increasingly difficult. French officials themselves were sometimes divided on what to do.

Settlers shared their views in their political and cultural groups and business associations. Newspapers and magazines in French were published for the settler communities, like La Tunisie Française. These platforms helped settlers follow discussions, read reports that matched their views, and understand their politicians' talking points. This strengthened their unity. While settlers had diverse views on issues in France, in North Africa, they united to defend their common advantages.

Even so, some French settlers supported North African political goals. Although a small minority, their numbers in Tunisia were enough to support the French-language publication Petit Monde. It published articles that tried to bridge the gap between groups. It was sympathetic to Tunisians and discussed self-governance. Other colons might criticize any European who broke ranks. One such dissenting colon was the French official and academic Jacques Berque. Another was the famous author Albert Camus, who felt conflicted about his native Algeria. His 1942 novel L'Étranger showed a young French colon and his social disconnection. Camus worked for understanding between the conflicting sides. Even after the French left, Berque remained connected to North Africa and its newly independent peoples.

French Government Policies

The French often presented a united front in Tunisia. But they brought their own national divisions from France. Despite these disagreements, many on the political left and in Christian churches eventually agreed to spread French culture in Africa and Asia. However, some people still opposed colonialism. Albert Sarrault, a leading French colonialist, said in 1935 that most French people didn't care about colonies.

In Tunisia, a hierarchy developed. French state projects came first, followed by the interests of French settlers. The more numerous Italian settlers were rivals of the French. Tunisian Jews, many of whose families had lived there for centuries, often felt caught between local traditions and new European ways. The majority Tunisian Muslims carefully watched the French rulers. They had different attitudes towards French policies: some contributed, some were neutral, some resisted, and later some became political opponents.

Under French rule, various activities were encouraged. The Church sent missionaries from the new cathedral in Tunisia. They went south across the Sahara to what became Francophone Black Africa, setting up many mission communities. However, the Eucharistic Congress of 1930 in Tunis drew public criticism from Muslims.

Protectorate projects hired civil engineers and city planners. They designed and built many public improvements. These served community needs for water, communication, health, sanitation, and transportation. Life became more comfortable. Business opportunities increased.

Tunisians appreciated these improvements. But they noticed the advantages the Protectorate gave to European newcomers. Community leaders began to appeal to the French state's stated values, like droit humane (human rights). They wanted equal treatment with the French colons. But at first, these appeals often led to disappointment. Many Tunisians became cynical about the Protectorate's claims. Mass movements arose.

Not all French officials were unresponsive. From the start, the basic nature of the colonial project was debated. Various reasons were given for the Protectorate: for money and resources, for export markets, for cultural expansion and national prestige, for jobs for settlers, or as a military frontier. French policy could shift depending on which administrator made choices and the immediate situation. So, French policy was not always consistent. In the later decades, local French officials increasingly tried to address the needs and demands of the Tunisian people. The Protectorate sometimes faced its own conflicting goals, leading to difficult decisions.

Art and Culture in Tunisia

Traditional arts continued in Tunisia. For example, in music, the ma'luf is a form of Andalusian music. For the first time, new recording techniques allowed music to be saved for later listening. All fine arts were stimulated and challenged. This was not only by European technology but also by French examples and art theories.

In literature, Arabic poetry continued to develop. But other writers adopted new forms like the novel, based on French literature. The building of theatres under the Protectorate also increased opportunities for public performances. These included older Tunisian forms and new types of shows. Modern inventions for capturing light and sound made a completely new art form possible: film.

Key Moments in History

After World War I: Versailles 1919

Organized nationalist feelings among Tunisians had been forced underground by the French after the 1912 protests. But they reappeared after the Great War. Abdel Aziz Tha'alibi traveled to Paris. He wanted to present Tunisia's case against the Protectorate at the Versailles Peace Conference. He also published his book La Tunisie martyre. This book supported a constitutional government based on the 1861 example.

Many things encouraged the nationalists. In 1919, the League of Nations was founded. Many nations pushed for self-rule there. Turkey under Atatürk rejected the Versailles borders. It successfully fought for its independence. The Bolshevik revolution in Russia created a new state that challenged the international order. It began to support groups to overthrow existing governments. The colonial system, though it looked strong, had been shaken by the war. Some people could see that it was the beginning of the end for colonies.

The Tunisian Destour Party

Nationalists formed the Destour (Constitution) Party in 1920. Its official name was Al-Hisb Al-Horr Ad-Destouri At-Tounsi or Le Parti Libre Constitutionnel Tunisien. Tha'alibi was a founding member. The party made an informal alliance with the Bey, which annoyed the French.

In 1922, Lucien Sanit, the new French Resident General, allowed minor reforms. These included a Ministry of Justice and a Grand Council of Tunisia. The Grand Council was only for advice, and the French had too many representatives. This setback caused problems in the Destour Party. Under French threat, Tha'alibi left Tunisia in 1923.

Nationalist attention turned to economic issues in 1924. A mutual aid society was started, but it didn't last through a period of strikes.

The Confédération Générale des Travailleurs Tunisiens (CGTT) was formed by M'hammad Ali with help from the Destour party. The CGTT was a nationalist alternative to the French union, the CGT, which was led by communists. The CGTT successfully recruited many Tunisian workers from the CGT. The CGTT was more active in Tunisian issues and nationalist politics. In 1924, the Protectorate jailed its leaders. The Destour party had already distanced itself. In the 1940s, Farhat Hached followed this example. He organized the Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT). It quickly formed a lasting alliance with the Neo-Destour party.

The Neo-Destour party was formed in 1934. This happened because of a split in the Destour's leadership. Habib Bourguiba and others started it as the next generation's continuation of the original Destour spirit. The French authorities later arrested its leaders and bothered the Neo-Destour. This reduced its presence and effectiveness.

World War II and Tunisia

Like in the first World War, Tunisian troops were sent to France to fight against German armies in World War II. Three infantry regiments arrived in Marseille starting in March 1940. They fought in the Battle of France. After the French defeat, they were back in Tunisia by September. But Tunisian units fought again. By November 1942, French forces in Tunisia were fighting on the Allied side. Tunisian troops under the French flag then fought the German and Italian armies in Tunisia. Later, Tunisian units joined the Allied invasion of Italy. They entered Rome and then fought in the liberation of France. By the end of the war in 1945, the Tunisians were exhausted.

After France fell in 1940, French authorities in Tunisia supported the Vichy regime. This regime governed the southern parts of France after its surrender to German forces. Many Tunisians felt some satisfaction at France's defeat. In July 1942, Moncef Bey became the ruler. He immediately took a nationalist stance. He asserted Tunisian rights against the new Resident General appointed by Vichy. He traveled the country, ignoring royal rules. Moncef Bey quickly became very popular as the new voice of Tunisians. He took the place of the Destour and Neo-Destour parties, which the French had suppressed.

Near Alexandria, Egypt, the German General Erwin Rommel lost the decisive battle of al-Alamein in November 1942. He lacked supplies and reinforcements. The fighting ended on November 4, 1942. Then came the Tunisia campaign. On November 7, the Allies under American General Dwight Eisenhower began landing forces in Morocco (Operation Torch). Meanwhile, the German Afrika Korps and the Italian Army retreated from Egypt westward to Tunisia. They set up defenses at the Mareth Line south of Gabès. The British followed them. With reinforcements, the Afrika Korps had some success against the "green" American and Free French forces advancing from the west. This allowed operations against the British at the Mareth Line, which ultimately failed. The Allies broke through the Axis lines. An intense Allied air campaign forced the Afrika Korps to surrender on May 11, 1943. The Italian Army fought a desperate last battle and surrendered two days later. Tunisia became a staging area for the invasion of Sicily later that year.

General Eisenhower later wrote about the occupation of Tunisia. He said they were not governing a conquered country. Instead, they were trying to gradually broaden the government's base. The final goal was to give all internal affairs to popular control.

After the Allied landings in Morocco in late 1942, German forces took over the governments of both Vichy France and Tunisia. During this time (November 1942 to May 1943), Moncef Bey "judiciously refused to take sides." However, he used his influence to appoint the first Tunisian government since 1881. This government included some pro-Allied elements. Later, after the Allied victory, French colons falsely accused Moncef Bey of being a German collaborator. They wanted him removed immediately, and they got their wish. "Late in 1943 Musif Bey was deposed by the French on the pretext that he had collaborated with the enemy."

Habib Bourguiba, the leader of the Neo-Destour party, was imprisoned in Vichy France. The Germans took him to Rome and honored him to further Italian plans for Tunisia. Then he was sent back to his Axis-occupied homeland. But Bourguiba remained pro-Independence without being anti-French (his wife was French). In Tunisia, some pro-German Destour leaders were willing to work with the Third Reich. This was despite Bourguiba's warnings. After the war, Bourguiba's American connections helped clear him of false collaboration charges. Then, with Salah Ben Youssef and others, he began rebuilding the Neo-Destour political organization.

After the War: A New World

After World War II, the French regained control of Tunisia and other territories in North Africa. But the fight for independence continued and grew stronger. This was happening all over Asia and Africa.

The Soviet Union, which claimed to be 'anti-colonialist', gained power after the war. Its ideas strongly criticized French rule in North Africa. Writers who were not communists also continued this criticism. During the French presence, North African resistance became stronger as independence movements grew. The works of the Algerian anti-colonial writer, Frantz Fanon, were especially critical. The United States, another major victor and power, also spoke out against colonies. This was despite its alliance with European colonial states. Within a few years of the war's end, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines all became independent.

In 1945, the Arab League was formed in Cairo. It soon included Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen. Soon, the Destour's Habib Bourguiba secretly traveled to Cairo. He lived there while promoting political causes, like the Maghreb Liberation Committee. Just as the League of Nations inspired national awareness after World War I, the founding of the United Nations after World War II did the same. The U.N. provided a place to discuss national independence before 'world public opinion'. So, the struggle for independence in Tunisia became part of a global conversation.

Tunisian Nationalism Grows

The Political Struggle

After World War II, the Neo-Destour Party reappeared. It was led by Habib Bourguiba and Salah ben Yusuf. Bourguiba had already gained strong support from the national labor union, the Union Générale des Travailleurs Tunisiens (UGTT). This union was the successor to the short-lived Tunisian union, the Confédération (CGTT), which the French had stopped in 1924. The UGTT was nationalist and not linked to the communist-led French union CGT. The UGTT quickly formed a lasting alliance with Neo-Destour. As the party's Secretary General, ben Yusuf worked to open it to all Tunisians. He formed alliances with big businesses, religious activists, and pan-Arab groups favored by the Bey.

In Paris in 1950, Bourguiba presented the French government with a plan for gradual independence. The French eventually introduced limited reforms. For example, nationalists would get half the seats in a legislative council, with French settlers keeping the other half. Because there was little progress, armed groups of Tunisians, called Fellagha, began to resist French rule in 1954. They started with attacks in the mountains.

Tunisians coordinated their struggle with independence movements in Morocco and Algeria. The Moroccan professor Abdullah Laroui later wrote about the similarities between the independence movements in these three North African countries.

Conflicts Within the Movement

During later negotiations with France, a conflict broke out between the rival leaders of Neo-Destour. Habib Bourguiba thought it was smart to accept temporary self-rule before pushing for full independence. Salah ben Yusuf demanded immediate full independence. In the political fight for control of the movement, Bourguiba won. Ben Yusuf was eventually expelled from Neo-Destour. He then left Tunisia and lived in Cairo.

Tunisia Gains Independence

Final Talks and French Departure

Finally, facing defeat at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam and a rising revolution in Algeria, France agreed to end its Protectorate in Tunisia. In the decades-long fight for independence, Neo-Destour leaders managed to gain independence for Tunisia through clever strategies.

In Tunisia, Albert Memmi offered a less harsh view of French settlers than Fanon. But he was still not very sympathetic. He wrote that if a colon's living standards are high, it is "because those of the colonized are low." Memmi described the settler's money-related reasons for being there:

Moving to a colony must first bring a lot of profit. You go to a colony because jobs are guaranteed, wages are high, careers grow faster, and business is more profitable. A young graduate gets a position, a public servant a higher rank, a businessman lower taxes, and an industrialist cheap raw materials and labor. Perhaps later, he dreams of leaving this profitable place and buying a house in his own country. But if his livelihood is threatened, the settler feels in danger and seriously thinks of returning home.

This paints a rather sad picture of the colon before their coming tragedy. After Tunisia became independent in 1956, the new government began to distinguish between its citizens and foreigners. Facing a big choice, most French residents, including families who had lived in Tunisia for generations, decided to return to their "own land." Tunisians filled the jobs they left behind. "Between 1955 and 1959, 170,000 Europeans—about two-thirds of the total—left the country." This difficult ending contrasts with the otherwise mixed but not entirely negative results of the French era. Jacques Berque wrote, "Greater progress would have to be made, great sufferings undergone before either side would consent to admit the other's [place in history]." Berque also warned against making "easy judgments" about the past.

See also

- History of Tunisia

- Hafsid dynasty

- Barbary Coast

- List of Beys of Tunis

- Italian Tunisians

- French conquest of Tunisia

- Tunisia Campaign

- Tunisia

- History of Africa

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |