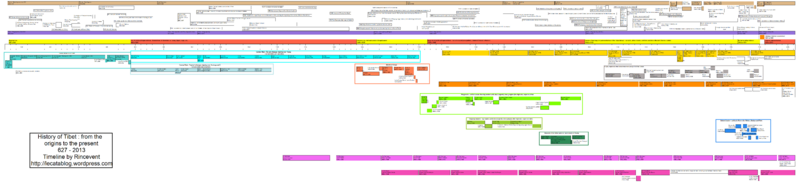

History of Tibet facts for kids

The Tibetan plateau is a huge, high land often called the "Roof of the World." People have lived here for a very long time, even before history was written down. Most of Tibet's story wasn't recorded until Tibetan Buddhism arrived around the 6th century. Ancient texts mention the kingdom of Zhangzhung, which existed before later Tibetan kingdoms and was the home of the Bon religion. Real historical records begin in the 7th century with the powerful Tibetan Empire.

After the empire broke apart, Buddhism became strong again between the 10th and 12th centuries. Later, the Mongol Empire controlled Tibet for a while. But by the 14th century, Tibet became independent again. It was ruled by different noble families for about 300 years. In the 17th century, the Dalai Lama, a very important Buddhist leader, became the head of Tibet with help from a Mongol group called the Khoshut Khanate.

In the early 1700s, another Mongol group, the Dzungar Khanate, took over Tibet. But a Chinese army from the Qing dynasty defeated them in 1720. Tibet then became part of the Qing dynasty until it fell in 1912. In 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama had to leave Tibet and go to India because of fighting with China. This event caused many Tibetans to become refugees, creating Tibetan communities in India, the United States, and Europe.

After China took control, questions about Tibet's independence and human rights became important around the world, especially with the 14th Dalai Lama speaking out. Chinese authorities have been accused of destroying religious sites and stopping people from having pictures of the Dalai Lama. During a time of great hunger in China called the Great Leap Forward, Tibet also suffered from a lack of food. China says it has helped Tibet by building new roads, schools, and industries, changing it from an old-fashioned religious government to a modern state.

Contents

- Tibet's Location: The Roof of the World

- Ancient Times in Tibet

- Early Kingdoms (around 500 BC – AD 618)

- The Tibetan Empire (618–842)

- Times of Change (9th–12th centuries)

- Mongol Control and Yuan Dynasty Rule (1240–1354)

- Tibet's Independence (14th–18th century)

- Qing Dynasty Rule (1720–1912)

- Tibet's Independence (1912–1951)

- People's Republic of China Rule (1950–present)

- See also

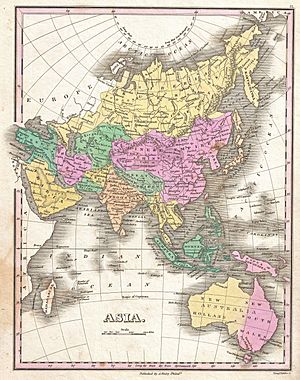

Tibet's Location: The Roof of the World

Tibet is located high in the mountains between China Proper and India. Huge mountain ranges like the Himalayas separate Tibet from its neighbors. Because it's so high up, Tibet is often called the "Roof of the World" or "the land of snows."

The Tibetan language is part of a larger language family called Sino-Tibetan languages. This family also includes Chinese.

Ancient Times in Tibet

Some discoveries suggest that very early humans might have traveled through Tibet half a million years ago. Even older hand and foot prints show that early human-like creatures lived on the high Tibetan Plateau over 169,000 years ago. Modern humans first lived there at least 21,000 years ago.

Later, around 3,000 years ago, new people from northern China came and mostly replaced the earlier groups. However, today's Tibetan people still have some genetic links to those very first inhabitants.

Large stone monuments, called megaliths, are found across the Tibetan Plateau. These might have been used to honor ancestors. Old Iron Age forts and burial sites have also been found. But it's hard to study these places because they are so high up and remote.

Early Kingdoms (around 500 BC – AD 618)

The Zhangzhung Kingdom

Some old Tibetan stories say that the Zhang Zhung people came from the Amdo region. They settled in what is now western Tibet. Zhang Zhung is believed to be the birthplace of the Bön religion.

Around the 1st century BC, a new kingdom grew in the Yarlung Valley. Its king, Drigum Tsenpo, tried to reduce the influence of the Zhang Zhung and their Bön priests. But Tsenpo was killed, and Zhang Zhung remained powerful until the 7th century. It was then taken over by the growing Tibetan Empire.

Early Tibetan Tribes

In AD 108, a group called the Kiang, or Tibetans, attacked Chinese areas. They were nomads from the southwest of Koko-nor. Chinese generals fought them off in several battles.

Chinese records from that time also mention a "Fu state" of Tibetan people. It was located far northwest of Sichuan. We don't know if this state was a very early version of the later Tibetan Empire.

First Kings of the Yarlung Dynasty

The first kings of the Yarlung Dynasty are mostly known through myths. There isn't enough proof to say for sure that they existed.

Traditional stories say Nyatri Tsenpo was the first Yarlung king. His capital was in the Yarlung Valley, near modern-day Lhasa. Some texts say he became king in 126 BC, others in 414 BC.

Myths describe Nyatri Tsenpo as a strange-looking creature. He was exiled from his home and welcomed in Tibet as a powerful being, becoming king.

These early kings were believed to be connected to the heavens by a special cord. They didn't die but went straight to heaven when their sons grew up. However, King Drigum Tsenpo's cord was cut during a fight, and he died. After that, kings left bodies, and Bön priests performed funeral rites.

Another myth says Tibetan people came from a monkey and a rock ogress. The monkey was a form of the Buddhist deity Avalokiteśvara. The ogress was a form of his partner, Dolma.

The Tibetan Empire (618–842)

The Yarlung kings slowly gained more control. By the early 6th century, many Tibetan tribes were under their rule. Namri Songtsen (570?–618?/629) was the 32nd Yarlung King. He took control of the area around Lhasa by 630 and conquered Zhangzhung. With this, the Yarlung kingdom became the powerful Tibetan Empire.

Namri Songtsen's government sent messages to China in 608 and 609. This was Tibet's first appearance on the world stage. From the 7th century, Chinese historians called Tibet "Tubo."

Tibetan history lists many rulers. Chinese records confirm some of them from the 7th century onwards. Three important emperors were Songtsen Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Ralpacan. They are known as "the three religious kings" because they helped bring Buddhism to Tibet. Songtsen Gampo (around 604–650) was the first great emperor. He expanded Tibet's power beyond Lhasa and is traditionally credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet.

Over the centuries, the empire grew larger. By the early 9th century, its influence reached as far south as Bengal and as far north as Mongolia.

The empire's large and varied lands, along with new ideas from its expansion, created challenges. Different groups often competed for power. For example, followers of the old Bön religion and ancient noble families often disagreed with the newly introduced Buddhism.

Times of Change (9th–12th centuries)

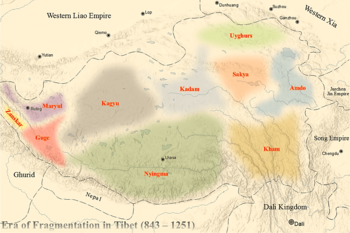

When Power Broke Apart

The Era of Fragmentation was a time in the 9th and 10th centuries when the strong central government of the Tibetan Empire fell apart. This period saw many rebellions against the old empire and the rise of local leaders. After the last emperor, Langdarma, died, there was a fight over who would rule next. This led to a civil war, which ended central rule in Tibet.

Langdarma's son, Pälkhortsän (865–895 or 893–923), kept some control over central Tibet for a while. His younger son, Thrikhyiding, moved to western Tibet and started a new local ruling family.

After the empire broke up in 842, Nyima-Gon, from the old royal family, founded the first dynasty in Ladakh. His kingdom was east of modern-day Ladakh. Nyima-Gon's oldest son ruled the Ladakh region. His two younger sons ruled western Tibet, starting the kingdoms of Guge and Zanskar–Spiti. Later, the king of Guge's oldest son, Kor-re (also called Jangchub Yeshe-Ö), became a Buddhist monk. He invited Atiśa to Tibet in 1040, which helped Buddhism become strong again.

Buddhism's Comeback in Tibet

Buddhism had quietly survived in the Kham region. The late 10th and 11th centuries saw a big return of Buddhism in Tibet. This happened as "hidden treasures" (terma) of Buddhist teachings were discovered. Buddhist influence grew from both the far east and far west of Tibet.

Muzu Saelbar (832–915), also known as Gongpa Rabsal, helped restart Buddhism in northeastern Tibet. He is seen as the founder of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. In the west, Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055) translated many texts and built temples. Important teachers from India were invited to Tibet again.

In 1042, Atiśa (982–1054 CE), a famous Buddhist teacher from India, came to Tibet. He later moved to central Tibet. His main student, Dromtonpa, started the Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism. This school influenced the development of today's "New Translation" schools.

The Sakya school, known as the "Grey Earth" school, was founded by Khön Könchok Gyelpo (1034–1102). It is led by the Sakya Trizin and is known for its scholarly traditions. A famous Sakya teacher was Sakya Pandita (1182–1251 CE).

Other important Indian teachers were Tilopa (988–1069) and his student Naropa (died around 1040 CE). The Kagyu school, meaning "Lineage of the Word," focuses on meditation experiences. Its most famous teacher was Milarepa, an 11th-century mystic.

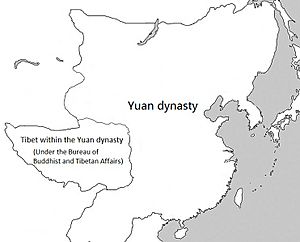

Mongol Control and Yuan Dynasty Rule (1240–1354)

During this time, the Sakya lamas ruled Tibet with the help of the Mongols. So, it's also called the Sakya dynasty period. The first known meeting between Tibetans and Mongols happened around 1221–22. A missionary named Tsang-pa Dung-khur met Genghis Khan.

Closer contact happened when the Mongols moved through the Sino-Tibetan borderlands to attack China. Some Tibetan stories say Genghis Khan planned to invade Tibet in 1206, but there's no proof of this.

The Mongols invaded Tibet in 1240 with about 30,000 soldiers. They withdrew in 1241 but returned in 1244. Köten demanded that the abbot of Sakya come to him. Sakya Paṇḍita arrived in 1246 and met Prince Köten the next year. The Mongols had already taken over eastern Tibet. In 1249, Sakya Paṇḍita was made the Mongol court's representative in Central Tibet.

Tibet became part of the Mongol Empire. Tibet kept some power over religious and local political matters. But the Mongols had overall control, sometimes using military force. This was a "two-power" system, with the Mongols having the main authority. Within the Mongol Empire in China, called the Yuan dynasty, Tibet was managed by a special department. This department also chose a local Tibetan leader, called a dpon-chen, who was approved by the Mongol emperor.

In 1253, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) became the Sakya leader at the Mongol court. Phagpa became a religious teacher to Kublai Khan. In 1260, Kublai Khan made Phagpa his "Imperial Preceptor." Phagpa developed the idea of a "priest-patron relationship" between Tibet and the Mongols. With Kublai Khan's support, Phagpa and his Sakya school became the most powerful political force in Tibet.

In 1265, Chögyal Phagpa returned to Tibet. He tried to make the Sakya school the main power. A census was done in 1268, and Tibet was divided into thirteen districts. By the end of the century, western Tibet was controlled by imperial officials, mostly Tibetans, who reported to the "Great Administrator."

The Sakya rule continued until the mid-14th century. It was challenged by a revolt from another Buddhist group, the Drikung Kagyu sect, in 1285. The Sakyas and eastern Mongols crushed the revolt in 1290, burning a monastery and killing many people.

Between 1346 and 1354, the House of Pagmodru took over from the Sakya. By 1358, central Tibet was controlled by the Kagyu sect. The next 80 years were quite stable. This period also saw the start of the Gelug school (also called Yellow Hats) by Tsongkhapa Lobsang Dragpa. Important monasteries like Ganden, Drepung, and Sera were founded near Lhasa. After the 1430s, Tibet entered another period of internal power struggles.

Tibet's Independence (14th–18th century)

As the Yuan dynasty declined, Central Tibet was ruled by different families from the 14th to the 17th centuries. Then, the Dalai Lamas took over. Tibet was largely independent for almost 400 years from the mid-14th century. Even though central authority was weak, the neighboring Ming dynasty of China didn't try to rule Tibet directly. They had some claims but mostly kept friendly ties with Buddhist leaders.

Family Rule in Tibet

Phagmodrupa Dynasty (14th–15th centuries)

The Phagmodru region was given to a Mongol leader in 1251. Later, the Lang family ruled this area. As Mongol influence weakened, Jangchub Gyaltsän (1302–1364) became the leader in 1322. He fought to get back Phagmodru lands that had been taken. After long legal battles, fighting broke out in 1346. Jangchub Gyaltsän was arrested but released. He defended Phagmodru and had military successes. By 1351, he was the strongest leader in Tibet. The fighting ended in 1354, and he established the Phagmodrupa dynasty. He ruled central Tibet until his death in 1364.

Under Jangchub Gyaltsän, Tibet saw a new cultural pride. This peaceful time helped literature and art grow. During this period, the scholar Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug sect, which would greatly shape Tibet's history.

Rinpungpa Family (15th–16th centuries)

Fights within the Phagmodrupa dynasty and strong local loyalties led to many internal conflicts. The Rinpungpa family, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), became the main political power after 1435.

Tsangpa Dynasty (16th–17th centuries)

In 1565, the Rinpungpa were overthrown by the Tsangpa Dynasty from Shigatse. This dynasty expanded its power across Tibet in the following decades. They supported the Karma Kagyu sect. The Tsangpa played a key role in the rise of the Dalai Lamas in the 1640s.

The Ganden Phodrang Government (17th–18th centuries)

The Ganden Phodrang was the Tibetan government started in 1642 by the 5th Dalai Lama. He had military help from Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Khanate. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet. The 5th Dalai Lama was given all political power by Güshi Khan.

The Rise of the Gelugpa School and the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lamas became powerful with the help of Mongol groups. Altan Khan, a Mongol king, invited Sonam Gyatso, the head of the Gelugpa school, to Mongolia in 1569 and again in 1578. Gyatso accepted the second invitation. They met and the Dalai Lama taught many people.

Sonam Gyatso announced that he was a new form of the Sakya monk Drogön Chögyal Phagpa. He said Altan Khan was a new form of Kublai Khan. They had come together to spread Buddhism. This helped make Buddhism popular among Mongol nobles. Also, Yonten Gyatso, the fourth Dalai Lama, was Altan Khan's grandson.

The Khoshut-Gelugpa Alliance

Yonten Gyatso (1589–1616), the fourth Dalai Lama, was not Tibetan. He died young in 1616.

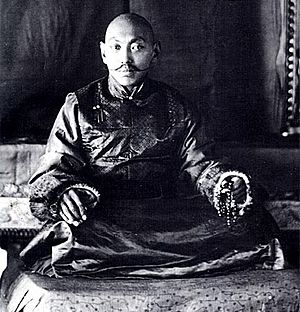

Lobsang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682), was the first Dalai Lama to truly hold political power over central Tibet.

The Fifth Dalai Lama's first helper, Sonam Rapten, united the Tibetan heartland under the Gelug school. He defeated rival groups and the Tsangpa prince in a long civil war. This was largely thanks to military help from Güshi Khan, the Khoshut Mongol leader. Some say Güshi Khan managed civil affairs, while others say he mostly stayed in Mongolia.

The 5th Dalai Lama and his close advisors, especially Sonam Rapten, set up a government called the Lhasa state. It was also known as the Ganden Phodrang, named after the Dalai Lama's home in Drepung Monastery.

Sonam Rapten was a strong supporter of the Gelugpa. Under his rule, other Buddhist schools were sometimes treated badly. Some say Jonang monasteries were closed or forced to change. However, the Dalai Lama later ordered an end to these harsh policies. The 5th Dalai Lama gained more control over his government after Sonam Rapten and Güshi Khan died in the 1650s.

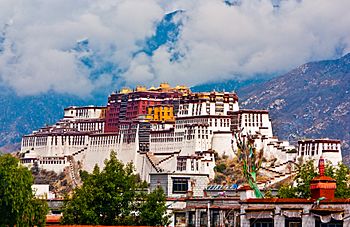

The 5th Dalai Lama started building the famous Potala Palace in Lhasa in 1645. In 1652, he visited the Shunzhi Emperor of the Qing dynasty in China. He was treated with great respect.

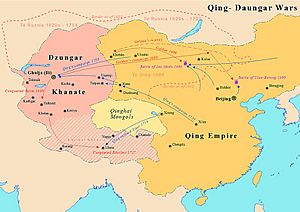

The 5th Dalai Lama's death in 1682 was kept secret for 15 years by his assistant, Desi Sangye Gyatso. The 6th Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, became leader in 1697. In 1705-06, a conflict led to Lhasa being taken over by Lha-bzang Khan, who killed the regent and removed the 6th Dalai Lama. A new leader was put in place until the Dzungar Khanate invaded in 1717. The Dzungars removed the Khoshut khan and the new leader. The 7th Dalai Lama was then installed. But the Dzungars treated the people badly. The Qing dynasty drove out the Dzungars in 1720.

Qing Dynasty Rule (1720–1912)

The Qing dynasty took control of Tibet after a Chinese army defeated the Dzungars in 1720. This rule lasted until the Qing dynasty fell in 1912. The Qing emperors sent officials called Ambans to Tibet. These Ambans commanded over 2,000 soldiers in Lhasa. They reported to a Qing government agency that managed the region. During this time, the Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet with support from the Qing dynasty.

Qing Control

How Qing Control Began

The Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty sent an army to Tibet. This was to fight the Dzungar Khanate who had taken over Tibet. With help from Tibetan forces, they drove the Dzungars out in 1720. They brought Kelzang Gyatso to Lhasa, and he became the 7th Dalai Lama. At this time, the Qing dynasty established its protection over Tibet. They placed soldiers in Lhasa. Eastern Tibet, called Kham, became part of the Chinese province of Sichuan. In 1721, the Qing set up a council in Lhasa with three Tibetan ministers. The Dalai Lama's role was mostly symbolic but still very important due to religious beliefs.

After the Yongzheng Emperor took over in 1722, fewer Qing soldiers were in Tibet. But some Lhasa nobles, who had sided with the Dzungars, killed the main minister and took control of Lhasa in 1727. Qing troops arrived in September and punished the anti-Qing group. The Dalai Lama was sent away. The Panchen Lama was brought to Lhasa and given power over western Tibet. This created a split in power between the two high lamas. Two ambans were placed in Lhasa with more Qing soldiers. By the 1730s, Qing troops were reduced again. A Tibetan leader named Polhanas gained more power. The Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in 1735, but Polhanas kept the political power. The Qing saw Polhanas as a loyal and effective ruler, so he remained powerful until his death in 1747.

Chinese soldiers were stationed in many places in Tibet during the Dzungar war. After 1728, the Qing used Chinese soldiers to guard Lhasa.

The Qing had made the regions of Amdo and Kham into the province of Qinghai in 1724. They also added eastern Kham to nearby Chinese provinces in 1728. The Qing government sent a resident commissioner (amban) to Lhasa. Polhanas' son, Gyurme Namgyal, took over after his father died in 1747. The ambans believed he was planning a rebellion, so they killed him. News spread, and a riot broke out in Lhasa. The angry crowd killed the ambans. The Dalai Lama stepped in and brought back order. The Qianlong Emperor sent Qing forces to punish those involved. The Emperor changed the Tibetan government again, giving the Dalai Lama nominal power but truly strengthening the new ambans.

Qing Control Grows

When Nepal invaded in 1791 and was defeated, Qing control over Tibet increased. From then on, all important matters had to go through the ambans. The ambans became more powerful than the Tibetan council and regents. They took charge of Tibet's border defense and foreign affairs. They also commanded the Qing soldiers and the Tibetan army. Trade and travel were restricted. However, some historians say these rules were not fully put into practice. In 1841, an Indian dynasty tried to take over western Tibet but was defeated.

In the mid-19th century, some Chinese soldiers from Sichuan settled in Lhasa. They married Tibetan women, and their families became part of Tibetan culture.

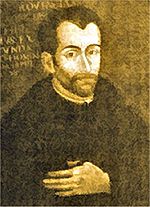

European Visitors to Tibet

The first Europeans in Tibet were Portuguese missionaries in 1624, led by António de Andrade. Tibetans welcomed them and let them build a church. More European missionaries came in the 18th century. But Tibetan lamas eventually opposed them and expelled them in 1745. Other visitors included George Bogle from Scotland in 1774. He came to Shigatse to study trade for the British East India Company. He also brought the first potatoes to Tibet.

After 1792, Tibet, influenced by China, closed its borders to Europeans. In the 19th century, only three Westerners reached Lhasa: Thomas Manning from England and two French missionaries, Huc and Gabet. Many others traveled in areas around Tibet.

During the 19th century, the British Empire was expanding from India into the Himalayas. The Russian Empire was also expanding into Central Asia. Both powers became suspicious of each other's plans in Tibet. Many explorers were interested in Tibet. In 1840, Sándor Kőrösi Csoma arrived in India, hoping to find the origin of the Magyar people, but he died before reaching Tibet.

In 1865, Great Britain secretly began mapping Tibet. They used trained Indian spies, disguised as pilgrims or traders, to measure distances and take readings. Nain Singh, the most famous, measured the location and height of Lhasa and mapped the Yarlung Tsangpo River.

British Invasions and Qing Control (1903−1904)

In the early 1900s, the British and Russian Empires were competing for power in Central Asia. The British couldn't talk to the Tibetan government. They were also worried about Tibet's dealings with Russia. So, in 1903–04, a British army led by Colonel Francis Younghusband went to Lhasa. Their goal was to force a trade agreement and stop Tibet from working with the Russians. In response, the Qing government in China clearly stated that China was in charge of Tibet. Before the British troops reached Lhasa, the 13th Dalai Lama fled to Outer Mongolia and then to Beijing in 1908.

The British invasion helped cause the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion at Batang monastery. Anti-foreign Tibetan lamas killed French missionaries, Chinese officials, and Christians. The Qing government crushed this revolt.

The Anglo-Tibetan Treaty of Lhasa of 1904 was followed by the Sino-British treaty of 1906. Beijing agreed to pay London money that Lhasa was forced to agree to in the 1904 treaty. In 1907, Britain and Russia agreed that they would only talk to Tibet through the Chinese government.

The Qing government in Beijing then sent Zhao Erfeng, the Governor of Xining, to "reintegrate Tibet into China." He was sent in 1905 (or 1908) on a mission to punish. His troops destroyed monasteries in Kham and Amdo. A process of making the region more Chinese began. The Dalai Lama fled again, this time to India, and was again removed from power by the Chinese. But the situation soon changed. After the Qing dynasty fell in October 1911, Zhao's soldiers rebelled and killed him. All remaining Qing forces left Tibet after the Xinhai Lhasa turmoil.

Tibet's Independence (1912–1951)

The Dalai Lama returned to Tibet from India in July 1912, after the fall of the Qing dynasty. He expelled the Chinese Amban and all Chinese troops. In 1913, the Dalai Lama announced that the relationship between the Chinese emperor and Tibet was like a "patron and priest," not one where Tibet was controlled by China. He said, "We are a small, religious, and independent nation."

For the next 36 years, Tibet was largely independent. China was going through its own problems, like civil war and World War II. Some Chinese sources argue that Tibet was still part of China during this time. A book from 1939 by a Swedish expert also placed Tibet as part of China. The USA also saw Tibet as a province of China in the 1940s. Other writers say Tibet was legally independent after a treaty with Mongolia in 1913.

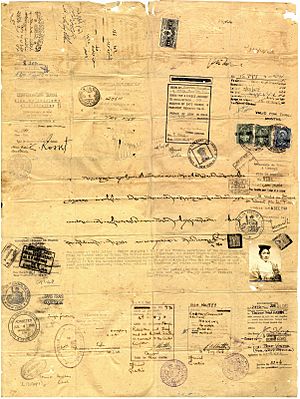

From 1913 to 1949, Tibet had very few contacts with the outside world. British representatives were stationed in some Tibetan towns. These "Trade Agents" were like diplomats for the British Government of India. In 1936–37, the British also set up a permanent office in Lhasa. This was after China sent a "condolence mission" to Lhasa when the 13th Dalai Lama died, which then stayed as a Chinese diplomatic post. After 1947, the British office was transferred to the new Indian government. The British, like the Chinese, encouraged Tibetans to keep foreigners out. Very few governments officially recognized Tibet as a fully independent country. In 1914, the Tibetan government signed the Simla Accord with Britain, giving some small areas to British India. The Chinese government said this agreement was illegal.

In 1932, a Chinese army defeated the Tibetan army in the Sino-Tibetan War. This happened when the 13th Dalai Lama tried to take land in Qinghai and Xikang. It was reported that China's central government encouraged the attack. A truce was signed, ending the fighting.

People's Republic of China Rule (1950–present)

In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party gained control of China. The Tibetan government then expelled all Chinese connected with the Chinese government. In October 1950, the People's Liberation Army entered the Tibetan area of Chamdo. They defeated the Tibetan army. In 1951, Tibetan representatives met with the Chinese government in Beijing. This led to a Seventeen Point Agreement. This agreement made China's control over Tibet official. However, the current Tibetan government-in-exile does not accept this agreement.

At first, China did not immediately change Tibetan society. From 1951 to 1959, traditional Tibetan society, with its lords and estates, continued as before. Even with many Chinese soldiers in Central Tibet, the Dalai Lama's government was allowed to keep important symbols of its past independence.

The Communists quickly ended slavery and serfdom. They also claim to have lowered taxes and started building projects. They opened non-religious schools, ending the monasteries' control over education. They also built water and electricity systems in Lhasa.

In eastern Tibet, land reform was fully put into action. This involved public humiliation, torture, and even death for "landlords."

By 1956, there was unrest in eastern Tibet where land reform had been fully implemented. These rebellions spread into other parts of Tibet.

In 1956–57, armed Tibetan fighters attacked Chinese army convoys. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) helped these fighters with training and supplies. The Dalai Lama's brothers were also involved in these efforts. Many Tibetan fighters dropped into the country by the CIA were from noble families. Most of them were never heard from again. Some reports say many ordinary Tibetans did not join the fighting at first. But other information suggests many thousands of Tibetans did take part in the rebellion. Soviet records show that Chinese communists used Soviet aircraft to bomb monasteries and for other operations in Tibet.

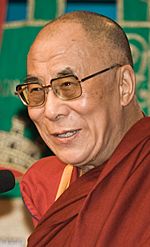

In 1959, China's military crackdown on rebels led to the "Lhasa Uprising." Full resistance spread across Tibet. Fearing the Dalai Lama would be captured, unarmed Tibetans surrounded his home. The Dalai Lama then fled to India.

From 1959 to 1962, Tibet suffered greatly from hunger during the Great Chinese Famine. This was caused by drought and Chinese policies. The Tenth Panchen Lama wrote a long letter in 1962 detailing the suffering of Tibetans.

In 1962, China and India fought a short war over the disputed Aksai Chin region. China won but pulled its troops back.

In 1965, the area that the Dalai Lama's government controlled was renamed the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). This region was supposed to have a Tibetan head of government. However, the real power is held by the Chinese Communist Party's First Secretary, who has never been Tibetan. The role of Tibetans in high positions in the Communist Party remains very small.

Most of Tibet's more than 6,000 monasteries were destroyed by the Chinese Communist Party between 1959 and 1961. In the mid-1960s, monastic lands were broken up, and non-religious education was introduced. During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards damaged cultural sites across China, including Tibet's Buddhist heritage.

In 1989, the Panchen Lama died at age 50.

China continues to say its rule has improved Tibet. But some foreign governments and groups like Human Rights Watch report human rights concerns. Most governments today recognize China's control over Tibet. No government recognizes the Government of Tibet in Exile in India.

Riots broke out again in 2008. Many Chinese people were attacked, and their shops were damaged. The Chinese government quickly responded with curfews and limited access to Tibetan areas. The world reacted strongly, with some leaders criticizing the crackdown and others supporting China's actions.

In 2018, the car company Mercedes-Benz apologized for "hurting feelings" in China by quoting the Dalai Lama in an advertisement.

Tibetans Living in Exile

After the Lhasa uprising and the Dalai Lama's escape in 1959, the government of India welcomed Tibetan refugees. India gave land to the refugees in Dharamsala, India. This is where the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile are now based.

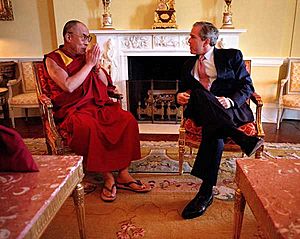

The situation of Tibetan refugees gained international attention when the Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. He received the prize for his peaceful protests against China's control of Tibet. He is highly respected and has met with many world leaders. He received the Congressional Gold Medal from President Bush in 2007. In 2006, he became one of only six people to receive honorary Canadian citizenship. China always protests any official contact with the exiled Tibetan leader.

The community of Tibetans living outside Tibet has grown since 1959. They have rebuilt Tibetan monasteries in India, which now house thousands of monks. They have also created Tibetan schools and hospitals. They founded the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives to keep Tibetan traditions and culture alive. Tibetan festivals, like Lama dances, Losar (the Tibetan New Year), and the Monlam Prayer Festival, continue in exile.

In 2006, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, said that "Tibet wants autonomy, not independence." However, the Chinese government still doesn't fully trust him.

Talks between the Dalai Lama's representatives and the Chinese government started again in May 2008 but had little result.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Tíbet para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Tíbet para niños

- 1959 Tibetan uprising

- 1987–1989 Tibetan unrest

- 2008 Tibetan unrest

- History of Central Asia

- History of India

- History of Ladakh

- History of Tibetan Buddhism

- List of rulers of Tibet

- Patron and priest relationship

- Pha Trelgen Changchup Sempa

- Protests and uprisings in Tibet since 1950

- Sinicization of Tibet

- Tibet

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |