History of United States prison systems facts for kids

Long ago, before the American Revolution, people in the United States punished criminals in many ways, like fines, forced work, public shaming, or even death. Prisons, like dungeons, existed, but they were mostly for holding people before trial. Over time, putting people in prison as a punishment became more common. This was seen as a kinder option than harsh physical punishments, especially by a group called the Quakers in Pennsylvania.

The way prisons were built and used in the U.S. changed a lot over three main periods. The first big change happened around the Jacksonian Era. Prisons became the main way to punish most crimes, and they often involved forced labor to help people change. By the time of the American Civil War, this was common everywhere.

The second big change came after the Civil War, during the Progressive Era. New ideas like parole (letting people out early under supervision), probation (supervision instead of prison), and flexible sentencing (prison time that could change) became popular.

The third and biggest change started in the 1970s. The number of people in prison in the U.S. grew hugely, more than ever before. Since 1973, the number of people in prison has increased five times! Today, about 2.2 million people are in prison, and around 7 million are under some kind of supervision, like parole or probation. These changes in prisons also affected how they were run, who was in charge, and the rights of prisoners.

Contents

- How Prisons Started in the United States

- Prisons in America: A Changing System

- How U.S. Prison Systems Developed Over Time

- Images for kids

How Prisons Started in the United States

Putting people in prison as a punishment is a fairly new idea in American and English law. Before the 1800s, it was rare for courts in British North America to sentence someone to prison. However, England had used prisons, like workhouses, since the 1500s. When the first prisons appeared in the U.S. after the Revolution, they were inspired by these older English models. For example, Massachusetts' Castle Island Penitentiary, built in 1780, was similar to the English workhouses.

Prisons in America: A Changing System

Early American prisons were influenced by English laws and also by religious ideas about punishment. Because there weren't many people in the eastern states, it was hard to follow all the criminal laws. But as the population grew, the prison system in the U.S. began to change.

Prisons are meant to keep people safe, maintain order, provide good conditions (like health care), and help prisoners change their behavior so they can return to their communities. The idea of holding criminals in confinement is very old. The Romans, for example, had a well-developed system for imprisoning different types of offenders.

Real reform in America began in 1789. After gaining independence, states like New York changed their laws because they seemed too harsh. Pennsylvania stopped punishing robbery and burglary with death, leaving only first-degree murder as a crime punishable by death. Other states also reduced their lists of crimes punishable by death. This meant there was a need for other punishments, which led to longer prison sentences.

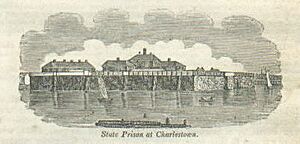

The oldest prison was built in York, Maine, in 1720. The very first jail that became a state prison was the Walnut Street Jail. This led to many state prisons being built across the eastern U.S. For example, Newgate State Prison in Greenwich Village was built in 1796, and New Jersey, Virginia, Kentucky, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maryland soon followed.

In the early 1800s, Americans wanted to reform prisons. They believed that prisons should help criminals become law-abiding citizens. The Auburn state prison was the first to try this idea. It aimed to keep inmates separate, teach them to obey rules, and use their labor for production. The goal was to reform prisoners, not just to scare them. Soon, another model, the Pennsylvania system, emerged. It was similar to Auburn but aimed to completely prevent human contact between inmates. Prisoners were kept in their cells alone, ate alone, and could only see approved visitors.

Prisons have changed a lot from the 1800s to today. By 1990, over 750,000 people were in state prisons or county jails. Prisons weren't built to hold so many people. With new materials and ideas, prisons changed physically to fit the growing population. While they still had high walls, they added modern technology like surveillance and electronic monitoring. Prisons also started to branch out into different types, like "open prisons" or "weekend prisons," to meet various needs.

The English Workhouse: An Early Prison Idea

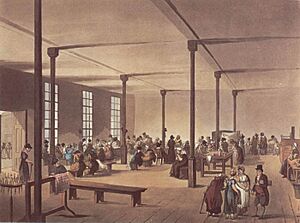

The English workhouse was an early idea that influenced prisons in the United States. It was first created to deal with poor people who were seen as "idle." Over time, English officials began to see the workhouse as a way to rehabilitate all kinds of criminals.

In the 1500s, many in England thought that property crimes happened because people were "idle." In 1557, the City of London reopened the Bridewell as a place for homeless people arrested in the city. People could be sent there for weeks or even years. Soon, "houses of correction" or "workhouses" like the Bridewell became common across England.

The workhouse wasn't just a place to hold people. Many hoped that hard labor in the workhouse would help residents become productive citizens. They also thought the threat of the workhouse would stop people from being homeless, and that inmate labor could help pay for the workhouse itself.

Even though workhouses first held homeless people, there were discussions about using them for other criminals. Thinkers like Thomas More suggested using forced labor instead of death as punishment. Over time, laws allowed people convicted of minor crimes to be sent to workhouses.

In the 1700s, even as England's harsh "Bloody Code" (which had many crimes punishable by death) was in place, hard labor in workhouses was seen as an acceptable punishment for various criminals. In 1779, during the American Revolution (which made sending convicts to America difficult), the English Parliament passed the Penitentiary Act. This law called for building two London prisons where prisoners would work hard all day, with strict control over their food, clothes, and communication. Although these specific prisons were never built, the idea of rehabilitative imprisonment through hard labor was important.

English Philanthropists and Prison Reform

Another group that supported prisons in England were religious leaders and kind-hearted people who wanted to make the criminal justice system less harsh in the 1700s. Early reformers like John Howard focused on the terrible conditions in jails where people waited for trial. But many also cared about the spiritual well-being of inmates and wanted to stop mixing all prisoners together. Their ideas about separating prisoners and using solitary confinement influenced American prisons.

Writers like Jonas Hanway began to focus on how to rehabilitate criminals after they were convicted. These philanthropists often believed that crime came from a person being far from God. They thought that restoring a criminal's faith could help them change.

Many in the 1700s suggested solitary confinement to help inmates become better people. They thought it would keep prisoners away from the bad influence of other inmates and help them focus on their spiritual recovery. They believed solitude was better than just hard labor, which only affected a person physically, not their inner self. This idea of a "penitentiary" (a place for repentance) was new and greatly influenced prisons in the U.S.

Building individual cells for each prisoner was expensive, which was a challenge. But by the 1790s, some solitary confinement facilities for convicted criminals appeared in England.

The idea of isolation and preventing "moral contamination" became a key part of early U.S. prisons. For example, the Auburn and Eastern State prisons in the 1820s used solitary confinement to try and morally rehabilitate prisoners. The idea of classifying inmates (dividing them by behavior, age, etc.) is still used in U.S. prisons today.

Rationalist Ideas for Prison Reform

A third group involved in English prison reform were the "rationalists" or "utilitarians." These thinkers used logic and reason, rather than religious texts, to guide how society should be organized.

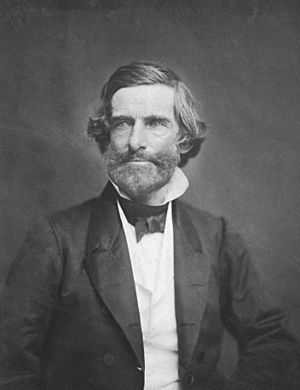

Philosophers like Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham developed a new idea about crime: that an action should be punished based on the harm it caused to society. For them, sins that didn't harm others weren't the court's business. Many rationalists believed that a criminal's behavior came from their environment.

Beccaria thought that if punishment was "rapid and infallible" (meaning quick and certain), then punishments could be less severe. He didn't disagree with common punishments like whipping, but he wanted them to be applied more consistently.

Other rationalists, like Jeremy Bentham, believed that simply deterring crime wasn't enough. They thought the social environment was the root of crime. Bentham agreed with philanthropists that offenders needed rehabilitation, but he believed the goal was to show convicts that crime was illogical, not that they were far from religion. For these rationalists, society was both the cause and the solution to crime.

Hard labor became a popular solution for rationalists. Bentham's famous 1791 design for the Panopticon prison called for inmates to work in solitary cells. Another rationalist, William Eden, helped draft the Penitentiary Act of 1779, which also called for hard labor.

While the rationalists had less direct impact on U.S. prisons, their ideas about how society influences crime and the importance of rehabilitation still echo in prison practices today.

How U.S. Prison Systems Developed Over Time

Even though convicts played a big part in British settlement of North America, putting criminals in prison on a large scale is a fairly new idea in American law. Prisons existed from the earliest English settlements, but their purpose changed in the early U.S. due to a widespread "penitentiary" movement. The way prisons look and work in the U.S. has continued to change because of new ideas, political shifts, and reform movements during the Jacksonian Era, Reconstruction Era, Progressive Era, and since the 1970s. However, using prison as the main way to punish criminals has stayed the same since it first became popular after the American Revolution.

Early American Settlements and Convict Transportation

Prisons and prisoners arrived in North America with the first European settlers. For example, some of Christopher Columbus's crew were convicts. By 1570, Spanish soldiers in St. Augustine, Florida, built the first major prison in North America. As other European countries competed for land, they also used convicts to fill their ships.

Convicts were very important for English settlement in what is now the U.S. In the late 1500s, Richard Hakluyt suggested sending many criminals to settle the New World for England. This idea gained traction in 1606 when the English crown increased its efforts to colonize.

Sir John Popham's colony in present-day Maine was filled with people from "all the gaols [jails] of England." The Virginia Company, which settled Jamestown, even allowed colonists to take Native American children to convert them. The colonists themselves lived almost like prisoners under the Company's governor.

When Sir Edwin Sandys took control of the Virginia Company in 1618, efforts to bring many unwilling settlers to the New World increased. Laws about homelessness (vagrancy) began to allow for penal transportation (sending criminals away) to the American colonies instead of death. The definition of "vagrancy" also became much wider.

Soon, a royal commission said that any criminal (except murderers, witches, or burglars) could be legally sent to Virginia or the West Indies to work on plantations. Sandys also suggested sending women to Jamestown as "breeders" to become wives for planters. Over sixty women soon made the trip, and more followed. King James I also sent "homeless" children to the New World as servants. Between 1619 and 1627, as many as 1,500 children were sent to Virginia. By 1619, African prisoners were also brought to Jamestown and sold as slaves.

This pattern of sending kidnapped children, women, convicts, and Africans to Virginia continued for almost two centuries. By 1650, most British people who came to colonial North America arrived as "prisoners" of some kind, whether as indentured servants, convict laborers, or slaves.

The trade in prisoners became a driving force of English colonial policy after 1660. By 1680, it was estimated that almost 10,000 people were sent to the Americas each year by the English crown.

Parliament sped up the prisoner trade in the 1700s. Under England's "Bloody Code," many convicted criminals faced the death penalty. However, pardons were common, often in exchange for agreeing to be sent to the colonies. In 1717, Parliament allowed English courts to directly sentence offenders to transportation. By 1769, transportation was the main punishment for serious crimes in Great Britain. Over two-thirds of those sentenced in London in 1769 were transported. The list of "serious crimes" that led to transportation kept growing. Historians estimate that as many as one-quarter of all British people who moved to colonial America in the 1700s were convicts. In the 1720s, James Oglethorpe settled the colony of Georgia almost entirely with convict settlers.

A typical transported convict in the 1700s was brought to North America on a "prison ship." When they arrived, they were cleaned up and prepared for a convict auction. Newspapers advertised the arrival of these "cargoes," and buyers would come to purchase convicts.

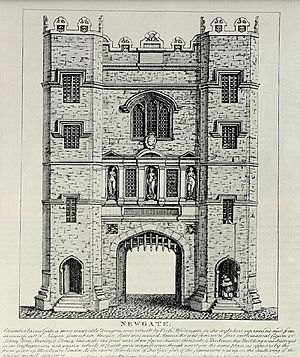

Prisons were crucial to this convict trade. Some old prisons, like the Fleet and Newgate, were still used. But often, an old house or private building would serve as a temporary holding place for those going to American plantations or the Royal Navy. Running secret prisons in port cities for people whose transportation wasn't strictly legal became a profitable business. Unlike modern prisons, these places mainly held people, rather than punishing them.

Many colonists in British North America didn't like convict transportation. As early as 1683, Pennsylvania tried to stop criminals from being brought into its borders. Benjamin Franklin called it "an insult." He even suggested sending rattlesnakes to England in revenge! But sending convicts to England's North American colonies continued until the American Revolution. Many English officials saw it as a necessary and more humane option given the harsh laws and crowded jails in England.

When the American Revolution ended the prisoner trade to North America, Britain's prison system became chaotic. Jails quickly filled with convicts who would have otherwise been sent away. Conditions got worse, which led to the work of prison reformer John Howard. His detailed study of British prisons, The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, was published in 1777, right after the Revolution began.

After the Revolution: New Prisons in the U.S.

The first big prison reform movement in the U.S. happened after the American Revolution, in the early 1800s. This reform was driven by population growth and social changes, which made people rethink how to deal with crime. Lawmakers and reformers began to push for a system of hard labor to replace less effective physical punishments. These early efforts led to the creation of the first penitentiary systems in the U.S.

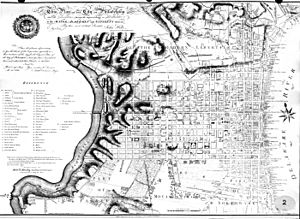

The 1700s brought huge changes to American life. The population grew quickly, and more cities appeared. After the Revolutionary War, this trend continued. Between 1790 and 1830, the population of the new states increased greatly, and cities became larger and more crowded. For example, New York's population increased five times!

People also moved around more in the 1700s, especially after the Revolution. Moving to cities, new territories, and up the social ladder made it harder for the old local ways of life to work. The Revolution made these changes even faster, leaving many families and soldiers struggling after the war. Crowded cities like Philadelphia seemed to blur class, gender, and racial lines, which worried some people.

These population changes happened at the same time as shifts in crime. After 1700, writings from ministers, newspapers, and judges suggest that property crime rates went up. Conviction rates also seemed to rise, especially in cities. People also noticed that former criminals moved around a lot.

Communities started to see a distinct "criminal class." In Philadelphia in the 1780s, authorities worried about taverns outside the city, which they saw as places for "alternative, interracial, lower-class culture" and "the very root of vice." In Boston, a higher crime rate led to a special urban court in 1800.

Traditional, community-based punishments became less effective. Forced labor, common in British and colonial American justice, almost disappeared. Fines and promises of good behavior, common in the colonial era, were hard to enforce among poor people who moved around a lot. As people's loyalty shifted from local areas to their new state governments, banishment (sending criminals away) also seemed wrong because it just passed criminals to a neighboring community. Public shaming punishments, like the pillory, depended on the public's participation. As society changed, people at public punishments sometimes sympathized with the accused instead of shaming them. In cities like Philadelphia, growing class and racial tensions after the Revolution led crowds to support the accused at executions.

Colonial governments began trying to reform their prison buildings and get rid of many traditional punishments even before the Revolution. Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut started efforts to change their systems so that hard labor in prison would be the only punishment for most crimes. Although the war interrupted these efforts, they were renewed afterward. After the Revolution, there was a new political mood that made lawmakers open to all kinds of legal changes, as they reshaped their laws to reflect their separation from England. People also wanted to get rid of punishments inherited from English law because they disliked England.

Reformers in the U.S. also began to think about how punishment itself affected crime. Some concluded that the harsh punishments from the colonial era, inherited from England, did more harm than good. William Bradford, an attorney, wrote in 1793 that the "mother country had stifled the colonists' benevolent instincts," forcing them to copy old, harsh customs that only made crime worse.

By the 1810s, almost every state had changed its criminal laws to make imprisonment (mostly with hard labor) the main punishment for all but the most serious crimes. Massachusetts began using short terms in workhouses for deterrence in the 1700s, and by the mid-1700s, laws requiring long-term hard labor in workhouses as punishment appeared. In New York, a 1785 law allowed officials to replace physical punishment with up to six months of hard labor in a workhouse. This program expanded to the whole state in 1796. Pennsylvania created a hard labor law in 1786. Hard-labor programs spread to New Jersey in 1797, Virginia in 1796, Kentucky in 1798, and Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maryland in 1800.

This shift to imprisonment didn't mean an immediate end to traditional punishments. Many new laws simply gave judges more choices, including imprisonment. For example, a 1785 Massachusetts law allowed judges to choose from whipping, hard labor, jail, the pillory, fines, or any combination for setting fire to a non-dwelling. Judges used this new freedom for twenty years before fines, imprisonment, or the death penalty became the only options. Other states, like New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, also took time to fully shift to incarceration.

Prison construction kept up with these legal changes. All states that changed their criminal laws to include imprisonment also built new state prisons. However, reformers in these early years focused more on the idea of imprisonment itself, rather than the daily life inside the prisons or how it affected offenders. Imprisonment seemed more humane than hanging or whipping, and it could theoretically match the punishment more closely to the crime. But it would take another period of reform, during the Jacksonian Era, for state prisons to truly become justice institutions.

The Jacksonian Era: New Prison Systems Emerge

By 1800, eleven of the sixteen U.S. states had some form of prison. But the main focus was still on the legal system, not on the prisons themselves. This changed during the Jacksonian Era, as ideas about crime continued to evolve.

Starting in the 1820s, a new type of institution, the "penitentiary," became central to criminal justice in the U.S. At the same time, other new institutions like asylums for the mentally ill and almshouses for the poor also emerged. For its supporters, the penitentiary was an ambitious plan to fix the disorder and immorality they believed caused crime in American society. Although it was adopted unevenly at first, the penitentiary became a well-known institution in the U.S. by the end of the 1830s.

The Pennsylvania System: Solitude and Reflection

The Pennsylvania system, first used in the early 1830s at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia and Western State Penitentiary in Pittsburgh, was designed to keep inmates completely separate at all times. Until 1904, prisoners entered with a black hood over their heads so they wouldn't know who their fellow convicts were. They were then led to their cell, where they would spend the rest of their sentence in almost complete solitude. Building Eastern State Penitentiary was very expensive, costing $750,000, one of the largest state expenses at the time.

Like its rival, the Auburn system, the Eastern State system believed in the inmate's ability to change individually. Solitude, not labor, was its main feature; labor was only allowed for inmates who earned the privilege. Prisoners at Eastern State had almost no contact with the outside world. Supporters claimed that a Pennsylvania inmate was "perfectly secluded from the world... hopelessly separated from... family, and from all communication with and knowledge of them for the whole term of imprisonment."

Supporters believed that through isolation and silence—complete separation from the bad influences of the outside world—inmates would begin to reform. They thought that each person's conscience would become their own punisher.

Proponents also said that the Pennsylvania system would only need mild discipline, believing that isolated men would not have the means or opportunity to break rules or escape.

In the end, only three prisons ever used the costly Pennsylvania system. However, almost all prison reformers of that time believed in the idea of solitary confinement. The system remained largely in place at Eastern State Penitentiary until the early 1900s.

The Auburn System: Work and Silence

The Auburn or "Congregate" System became the most common prison model in the 1830s and 1840s, spreading from New York's Auburn Penitentiary across the Northeast, Midwest, and South. The Auburn system combined working together in prison workshops during the day with solitary confinement at night. This became a widely accepted ideal for U.S. prison systems, even if it wasn't always fully put into practice.

Under the Auburn system, prisoners slept alone at night but worked together in a shared workshop during the day for their entire sentence. Prisoners at Auburn were not allowed to talk or even look at each other. Guards wore moccasins and patrolled secret passages behind the workshop walls, so inmates never knew if they were being watched.

One official said Auburn's discipline aimed to convince criminals that they were "no longer their own master" and had to learn a useful trade to earn an honest living after release. Inmates were not allowed to know about outside events. An early warden said Auburn inmates were "to be literally buried from the world." This system remained largely in place until after the Civil War.

Auburn was the second state prison built in New York State. The first, Newgate, in New York City, had few solitary cells. Its first keeper, Quaker Thomas Eddy, believed rehabilitation was the main goal of punishment. Eddy used solitary confinement with limited food as his main disciplinary tool, forbade guards from hitting inmates, and allowed "well-behaved" inmates supervised family visits every three months. Eddy tried to make prison labor profitable, hoping it would cover costs and provide money for inmates when they were released. However, discipline was hard to enforce, and major riots happened in 1799 and 1800, with the latter needing military help. Conditions worsened, especially after a crime wave following the War of 1812.

New York lawmakers funded Auburn prison to fix Newgate's problems and overcrowding. From the start, Auburn officials chose a harsher style than Eddy's "humane" approach at Newgate. Floggings (whippings) were allowed for rule-breaking under an 1819 law, which also permitted stocks and irons. The practice of giving convicts some of their earnings upon release was stopped. The harshness of the new system likely caused more riots in 1820, leading to the creation of a New York State Prison Guard to handle future problems.

Officials at Auburn also started classifying inmates after the riots: (1) the worst were kept in constant solitary confinement; (2) middle offenders were kept in solitary but worked in groups when well-behaved; and (3) the "least guilty" slept in solitary and worked in groups. A new solitary cell block for the "hardened" offenders opened in December 1821. However, within a year, five of these men died, forty-one were seriously ill, and several went insane. Governor Joseph C. Yates was so shocked by their condition that he pardoned several of them.

Auburn faced another scandal when a female inmate became pregnant in solitary confinement and later died after beatings and pneumonia. (Women were part of the prison population for washing and cleaning, but the first separate women's prison in New York wasn't built until 1893.) A jury convicted the keeper who beat the woman, but he kept his job. A grand jury investigation into the prison's management followed, but it was difficult because convicts couldn't testify in court. Still, the grand jury found that guards were allowed to whip inmates without a higher official present, which was against state law. No officers were prosecuted, and whipping increased at Auburn and the newer Sing Sing prison.

Despite its early scandals and political struggles, Auburn remained a model prison nationwide for decades. Massachusetts opened a new prison based on the Auburn system in 1826. Within ten years of Auburn's existence, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia all built prisons like it. By the start of the American Civil War, Illinois, Indiana, Georgia, Missouri, Mississippi, Texas, and Arkansas were all trying to set up Auburn-style prisons.

The widespread shift to penitentiaries in the U.S. before the Civil War changed where and how criminals were punished. Offenders were now taken to centralized prisons, often hidden from public view. This largely ended community involvement in the punishment process, though many prisons allowed visitors to see inmates for a fee throughout the 1800s.

The South and Prisons Before the Civil War

Before the American Civil War, crime wasn't a major concern in the Southern United States. Southerners often saw crime as a problem for the North. A traditional system of settling disputes, based on honor, meant that personal violence was common in the South. Southern prisons only held the most serious criminals. Most criminals remained outside formal state control, especially outside Southern cities.

Southern Politics and Opposition to Prisons

Historical records show that Southern states had unique political concerns about building prisons before the Civil War. Debates about "republicanism" (the role of the state in governing society) became a key part of the discussion about Southern prisons.

Many Southerners believed that "republicanism" meant freedom from anyone else's control. They thought that centralized power, even for a government trying to improve society, would cause more harm than good. This view was partly shaped by slavery, which created a rural, local culture where people distrusted powerful strangers. In this environment, giving up individual freedoms, even for criminals, for some idea of "social improvement" was often disliked.

However, some Southerners supported prisons. They believed that freedom would grow best under a strong state government that made criminal law more effective by ending brutal practices and offering criminals a chance to reform. Some also thought prisons would remove "depraved" people who threatened the republican ideal. The idea of keeping up with the world's "progress" also motivated Southern reformers.

A large part of the Southern population did not support building prisons. When voters in Alabama and North Carolina had a chance to vote on prisons, the idea lost by a lot. Some saw traditional public punishments as the most "republican" way to do justice because they were open to everyone. Some worried that since prison suffering would be much worse than traditional punishments, Southern juries would continue to acquit people. Religious leaders also opposed prisons, especially if they meant reducing the death penalty, which they saw as a biblical requirement for certain crimes.

Opposition to prisons crossed political parties. But Southern governors consistently and enthusiastically supported prisons. Their reasons aren't entirely clear: perhaps they wanted the extra jobs a prison would create, or they were genuinely worried about crime, or both. Grand juries, made up of Southern "elites," also regularly called for prisons.

Ultimately, prison supporters won in the South, just like in the North. Southern lawmakers passed prison laws before the Civil War, often despite public opposition. Their reasons were mixed. Some lawmakers, often from elite classes, might have believed they knew what was best for their people. They might also have wanted to control the lower classes, even while presenting their prison efforts as benevolent. Historians suggest that Southern hesitation about prisons, especially in South Carolina, came from the slave system, which made the idea of a white criminal underclass undesirable.

Building Prisons in the South

Southern states built prisons alongside Northern ones in the early 1800s. Virginia (1796), Maryland (1829), Tennessee (1831), Georgia (1832), Louisiana and Missouri (1834–1837), and Mississippi and Alabama (1837–1842) all built prisons before the Civil War. Only North Carolina, South Carolina, and mostly unsettled Florida did not build any prisons before the war.

Virginia was the first state after Pennsylvania, in 1796, to greatly reduce the number of crimes punishable by death. Its lawmakers also called for building a "gaol and penitentiary house" as the main part of a new justice system. Designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Virginia's first prison in Richmond looked like Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon design. All inmates had to spend a mandatory period in solitary confinement when they first arrived.

Unfortunately, Virginia's first prison was built next to a stagnant, sewage-filled pool. The cells had no heating, and water seeped from the walls, causing inmates' hands and feet to freeze in winter. Prisoners couldn't work during their solitary time, which they spent completely isolated in near-total darkness. Many went insane. Those who survived solitary joined other inmates in the prison workshop to make goods for the state militia. The workshop never made a profit, and escapes were common.

Despite Virginia's example, Kentucky, Maryland, and Georgia all built prisons before 1820, and this trend continued in the South. Early Southern prisons were known for escapes, violence, and arson. The personal reform of inmates was mostly left to underpaid prison chaplains. Strong public opposition and severe overcrowding were common in Southern prisons before the Civil War. But once established, Southern prisons developed their own complex histories of change and stagnation, good and bad wardens, prosperity and poverty, fires, escapes, and political attacks.

During the time of slavery, few black Southerners in the lower South were imprisoned, and almost no slaves were imprisoned. Slaves accused of crimes were often tried informally on plantations. Most Southern inmates before the Civil War were foreign-born white people. However, in the upper South, free black people made up a significant (and very high) one-third of state prison populations. Governors and lawmakers in both the upper and lower South worried about racial mixing in their prisons. Virginia even tried selling free black people convicted of "serious" crimes into slavery for a time, until public opposition led to the law being repealed (but only after forty people were sold).

Very few women, black or white, were imprisoned in the South before the Civil War. But for those who were, conditions were often "horrendous." Female inmates in the South did not have specialized facilities, unlike in many Northern prisons.

Like in the North, the costs of imprisonment worried Southern authorities, perhaps even more so. Southern governors before the Civil War generally had little patience for prisons that didn't make a profit or at least break even. Southern prisons used many of the same money-making tactics as Northern ones. They earned money by charging visitors fees and by using convict labor to produce simple goods like slave shoes, wagons, pails, and bricks. But this caused unrest among free workers and tradesmen in Southern towns and cities. To avoid these conflicts, some states, like Georgia and Mississippi, experimented with prison industries for state-run businesses. In the end, few prisons, North or South, made a profit before the Civil War.

However, foreshadowing later developments, Virginia, Georgia, and Tennessee began considering leasing their convicts to private businesses by the 1850s. Prisoners in Missouri, Alabama, Texas, Kentucky, and Louisiana were all leased out before the Civil War under various arrangements, some inside the prison and others outside.

The Reconstruction Era: Changes After the Civil War

The American Civil War and its aftermath brought huge changes to Southern society and its justice system. As formerly enslaved people became free, they came under the control of local governments for the first time. At the same time, the market economy began to affect parts of the South that hadn't been touched before. Widespread poverty in the late 1800s changed the South's old race-based social structure. In cities like Savannah, Georgia, old rules about race began to break down almost immediately after the war. Local police forces, weakened by the war, couldn't enforce the racial order as they had before. White people, suffering from poverty and anger, were also not as united in policing race as they had been. By the end of Reconstruction, a new system of crime and punishment emerged in the South: a mix of racialized forced labor, with convicts leased to private businesses, which lasted well into the 1900s.

Power Struggles Over Justice in the South

The biggest change in crime and punishment in the 1800s South was "the state's assumption of control over blacks from their ex-masters." This process was slow and difficult, but it began the moment masters told their slaves they were free. In this situation, the Freedmen's Bureau (a federal agency) competed with Southern white people—through official government groups and informal ones like the Ku Klux Klan—over different ideas of justice in the post-war South.

Southern white people mostly tried to save as much of the old system as possible after the American Civil War, waiting to see what changes would be forced upon them. The "Black Codes" passed almost immediately after the war (Mississippi and South Carolina passed theirs in 1865) were an early effort. Although they didn't use racial terms, the Codes defined and punished a new crime, "vagrancy" (homelessness), broadly enough to ensure that most newly free black Americans would remain in a state of forced labor. The Codes gave local judges and juries a lot of power to carry out this mission: County courts could choose punishments that weren't available before. Punishments for vagrancy, arson, and burglary—which white people thought were especially "black crimes"—became much harsher after the war.

Soon after the fighting ended, black "vagrants" in Nashville, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana, were being fined and sent to city workhouses. In San Antonio, Texas, and Montgomery, Alabama, free black people were arrested, imprisoned, and forced to work on the streets to pay for their own upkeep.

At the same time that Southern governments passed the "Black Codes," they also began to change the state's prison system to make it an economic tool. The use of forced labor by Southern state governments after the Civil War was an "important bridge" between an agricultural economy based on slavery and the new industrialization of the South.

Many prisons in the South were in bad shape by the end of the American Civil War, and state budgets were empty. Mississippi's prison, for example, was destroyed during the war. In 1867, the state's military government began leasing convicts to rebuild damaged railroads and levees. By 1872, it was leasing convicts to Nathan Bedford Forrest, a former Confederate general and slave trader, who was also the first leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

Texas also faced a major economic downturn after the war. Its lawmakers passed tough new laws calling for forced inmate labor inside prisons and on public works projects outside. Soon, Texas began leasing convicts to railroads, irrigation projects, and mines.

Virginia's prison in Richmond collapsed after the city surrendered in 1865, but occupying Union forces gathered as many convicts as they could to put them back to work. Alabama began leasing out its Wetumpka Prison to private businesses soon after the Civil War.

During the Reconstruction Era, the North Carolina legislature allowed state judges to sentence offenders to work on chain gangs on county roads, railroads, or other improvements for up to one year. North Carolina had not built a prison before the Civil War and planned to build an Auburn-style prison to replace forced labor. But corruption meant a new prison wasn't built, and North Carolina convicts continued to be leased to railroad companies.

Formerly enslaved black people became the main workers in the South's new forced labor system. Those accused of property crimes—white or black—had the highest chance of conviction in post-war Southern courts. But black property offenders were convicted more often than white ones. Overall, conviction rates for white people dropped significantly after the war.

The Freedmen's Bureau, responsible for carrying out federal reconstruction in the former Confederate states, was the main group that opposed the increasing racial bias in Southern criminal justice. The Bureau believed in fair legal processes and aimed to ensure black people's legal equality. The Bureau ran courts in the South from 1865 to 1868 to handle minor cases involving formerly enslaved people. Ultimately, the Bureau largely failed to protect formerly enslaved people from white violence or from the unfair Southern legal system, though it did provide much-needed services like food, clothing, and school support.

In rural areas of the South, the Freedmen's Bureau was only as strong as its isolated agents, who often couldn't enforce their will against local white people. Lack of staff and local white resentment led to early compromises where Southern civilians were allowed to serve as magistrates on the Freedmen's Courts, even though many formerly enslaved people opposed this.

In cities like Savannah, Georgia, the Freedmen's Courts seemed even more willing to enforce the wishes of local white people, sentencing formerly enslaved people (and Union Army veterans) to chain gangs, physical punishments, and public shaming. The Savannah Freedmen's Courts even approved arrests for "offenses" like "shouting at a religious colored meeting" or speaking disrespectfully to a white man.

The Bureau's influence on crime and punishment after the war was temporary and limited. The U.S. Congress believed that only its federal intervention could bring true republicanism to the South, but Southerners resented this as a violation of their own republican ideals. Southerners had always preferred less formal law, and once they linked formal law with outside oppression, they saw little reason to respect it. This resentment led to vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan, though the Klan was a relatively short episode in a long history of violence in the South.

Formerly enslaved people in the Reconstruction-era South also tried to fight white supremacist violence and injustice. In March 1866, Abraham Winfield and ten other black men asked the head of the Georgia Freedmen's Bureau for help against the unfairness of the Bureau's Court in Savannah. In rural areas, black people met white vigilante violence with their own violence. But with the withdrawal of the Freedmen's Bureau in 1868 and continued political violence from white people, black people ultimately lost this struggle. Southern courts were largely unable to bring white people to justice for violence against black Southerners. By the early to mid-1870s, white political control was re-established across most of the South.

In Southern cities, a different kind of violence emerged after the war. Race riots broke out almost immediately and continued for years. Poverty and old legal restrictions on black people were a main cause of these clashes. White people resented labor competition from black people in the struggling post-war Southern economy, and police forces, often made up of unreconstructed Southerners, frequently used violence. The ultimate goal for both black and white people was to gain political power in the chaos after the war; again, black people ultimately lost this struggle during Reconstruction.

The Start of the Convict Lease System

Convict leasing, which had been used in the North since early prison days, was adopted by Southern states in a big way after the American Civil War. Using convict labor remained popular nationwide after the war. A 1885 survey reported that 138 institutions used over 53,000 inmates in industries, producing goods worth $28.8 million. While this was a small amount compared to goods produced by free labor, prison labor was big business for those involved in certain industries.

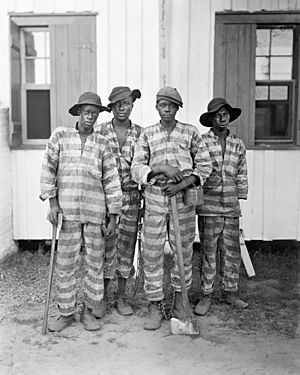

However, convict leasing in the post-war South played a more central role in crime and punishment than in the North. It continued with the approval of leading Southern men well into the 1900s. For over half a century after the Civil War, convict camps were common across the South, and thousands of men and women—most of them formerly enslaved—spent years in this system. Wealthy individuals, from both North and South, bought years of these convicts' lives and put them to work in large mining and railroad operations, as well as smaller businesses. On average, the death rate in Southern leasing arrangements was three times higher than in Northern prisons.

The convict lease system in the South wasn't just an attempt by state governments to bring back slavery. It showed how race relations continued but also how the Southern economy fundamentally changed after the war. For the first time, millions of formerly enslaved people came under the control of state prison systems. At the same time, new industries in the South faced a shortage of money and workers. Formerly enslaved people were the easiest group to force into service and adapt to these new industries.

Ultimately, the longest legacy of the system may be as a symbol of injustice and inhumanity in the white South. In 1912, one expert called the Southern convict "the last surviving vestige of the slave system." A Northern writer in the 1920s called the Southern chain gang the South's new "peculiar institution".

Southern prisons from before the Civil War generally continued to fall into disrepair after the war, becoming mere outposts of the much larger convict labor system. One by one, Southern prison systems had fallen apart during the American Civil War. Mississippi sent its prisoners to Alabama for safety during a Northern invasion. Louisiana put its prisoners into a single city workhouse. Arkansas released its convicts in 1863 when the Union Army entered its borders. Occupied Tennessee hired out its prisoners to the U.S. government, while Georgia freed its inmates as General William Tecumseh Sherman marched toward Atlanta in 1864. With the fall of Richmond, most of Virginia's prisoners escaped.

The convict lease system slowly emerged from this chaos, just as the penitentiary itself had years before. The penitentiary had become a Southern institution by this point, and getting rid of it completely would have required a major overhaul of state criminal laws. Some states, like Georgia, tried to revive their prison systems after the war, but they first had to deal with crumbling state buildings and a growing prison population. The three states that hadn't built prisons before the Civil War—the Carolinas and Florida—rushed to build them during Reconstruction.

But many Southern states—including North Carolina, Mississippi, Virginia, and Georgia—soon turned to the lease system as a temporary solution, as rising costs and convict populations overwhelmed their limited resources. The South "stumbled into the lease," trying to avoid large expenses while hoping a better plan would appear. These leasing arrangements were an "important bridge" between an agricultural economy based on slavery and the industrialization of the New South. This may explain why support for the convict lease was widespread in Southern society. No single group—black or white, Republican or Democrat—consistently opposed the lease once it gained power.

The type of labor convicts performed changed as the Southern economy evolved after the American Civil War. Former plantation owners benefited early on, but new industrial businesses—like phosphate mines and turpentine plants in Florida, and railroads across the South—soon demanded convict labor. The South had a severe labor shortage after the war, and there weren't enough displaced farm workers to meet the needs of factory owners, as there had been in England.

The lease system was useful for capitalists who wanted to make money quickly: Labor costs were fixed and low, and labor uncertainty was almost gone. Convicts could be, and were, pushed to limits that free laborers wouldn't tolerate. While labor unrest and economic problems continued to affect the North and its factories, the lease system protected its beneficiaries in the South from these outside costs.

In many cases, the businessmen who used the convict-lease system were also the politicians who ran it. The system became a "mutual aid society" for the new capitalists and politicians who controlled the white Democratic governments of the New South. So, officials often had something to hide, and reports on leasing operations often avoided or ignored the terrible conditions and death rates.

In Alabama, 40 percent of convict lessees died during their term of labor in 1870. In Mississippi, lessees died at nine times the rate of inmates in Northern prisons throughout the 1880s. One man who had been in the Mississippi system claimed that reported death rates would have been much higher if the state hadn't pardoned many sick convicts before they died, so they could die at home instead.

Compared to non-leasing prison systems nationwide, which only recovered 32 percent of expenses on average, convict leasing systems earned average profits of 267 percent. Even compared to Northern factories, the lease system's profitability was real and lasted well into the 1900s.

Exposés (reports exposing bad conditions) on the lease system began appearing more often in newspapers, state documents, Northern publications, and national prison association publications after the war. Mass grave sites containing the remains of convict lessees have been found in Southern states like Alabama, where the United States Steel Corporation bought convict labor for its mining operations in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The focus of Southern justice on racial control after the war greatly affected who was in the lease system. Before the Civil War, almost all Southern prisoners were white, but under post-war leasing arrangements, almost all (about 90 percent) were black. Before the war, white immigrants made up a large share of the South's prison population, but they almost disappeared from prison records after the war. This was likely because white immigrants generally avoided the post-war South due to its poor economy and the big increase in labor competition from formerly enslaved people. Also, post-war Southern police forces focused less on crime committed by white people.

The source of convicts also changed after the war. Before the American Civil War, rural counties sent few defendants to state prisons, but after the war, rural courts became steady suppliers to their states' leasing systems (though cities remained the largest supplier). Savannah, Georgia, for example, sent convicts to leasing operations at about three times the number its population would suggest, a pattern made worse by the fact that 76 percent of all black people convicted in its courts received a prison sentence.

Most convicts were in their twenties or younger. The number of women in Southern prison systems increased after the war to about 7 percent, a major increase for the South, which had previously prided itself on the good morals of its (white) female population. Almost all of these women were black.

Officials who ran the South's leasing operations tried to keep strict racial separation in the convict camps, refusing to recognize social equality between the races, even among criminals. White people who ended up in Southern prisons were considered the lowest of their race. Some lawmakers even used racial slurs for white prisoners.

The Southern lease system was not a "total system." Most convict-lease camps were spread out, with few walls or security measures—though some Southern chain gangs were transported in open-air cages to work sites and kept in them at night. Order in the camps was generally weak. Escapes were frequent, and the brutal punishments were given with a clear sense of desperation.

Reflecting changing crime patterns in Southern courts, about half of prisoners in the lease system were serving sentences for property crimes. Rehabilitation played no real role in the system.

Some supporters of the lease claimed it would teach black people to work, but many observers came to realize that the system greatly harmed any moral authority white society had. Time in prison came to carry little shame in the black community, as preachers and leaders spread word of its cruelty.

White people were not united in defending the lease system during the Reconstruction Era. Reformers and government insiders began condemning the worst abuses early on. Newspapers started to criticize it by the 1880s, though they had defended it right after the Civil War. But the system also had its defenders—sometimes even the reformers themselves, who disliked Northern criticism even when they agreed with its points. The "scientific" racial attitudes of the late 1800s also helped some supporters ease their doubts. One commentator wrote that black people died in such numbers on convict lease farms because of their "inferior, uneducated" blood.

Economic concerns, rather than moral ones, led to the more successful attacks on leasing. Labor groups launched effective opposition movements after the war. Birmingham, Alabama, and its Anti-Convict League, formed in 1885, were at the center of this movement. Coal miner revolts against the lease happened twenty-two times in the South between 1881 and 1900. By 1895, Tennessee gave in to its miners' demands and abolished its lease system. These revolts notably crossed racial lines. In Alabama, white and black free miners marched together to protest the use of convict labor in local mines.

In these confrontations, convict labor seemed more important to free workers than it actually was. Only 27,000 convicts were in some form of labor arrangement in the 1890s South. But the nature of Southern industry and labor groups—which tended to be smaller and more concentrated—meant that a small number of convicts could affect entire industries.

The Progressive Era: Ending the Convict Lease

The Slow End of Convict Leasing

Just as the convict lease system slowly emerged in the post-war South, it also slowly disappeared.

Although Virginia, Texas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri used Northern-style manufacturing prisons in addition to their farms, as late as 1890, most Southern convicts still served their sentences in convict camps run by private businessmen. But the 1890s also marked the beginning of a gradual shift towards compromise over the lease system, in the form of state-run prison farms. States began to remove women, children, and the sick from the old privately run camps during this period, to protect them from "bad criminals" and provide a healthier environment and work system. Mississippi passed a new state constitution in 1890 that called for the end of the lease by 1894.

Despite these changes and ongoing attacks from labor movements and political groups, only two Southern states besides Mississippi ended the system before the 1900s. Most Southern states did bring their systems under tighter control and increasingly used state penal farms by the 1900s, which led to improved conditions and a drop in death rates. Georgia abolished its system in 1908, after a report by Charles Edward Russell in Everybody's Magazine revealed "hideous" conditions on lease projects. Florida's prison camps remained in use until 1923.

Replacements for the lease system, such as chain gangs and state prison farms, were not so different from what came before. An example of the lasting influence of the lease system can be found in the Arkansas prison farms. By the mid-1900s, Arkansas' male prison system still had two large prison farms, which remained almost totally cut off from the outside world and operated much as they had during the Reconstruction Era. Conditions in these camps were so bad that, as late as the 1960s, an Oregon judge refused to send back escapees from Arkansas who had been caught in his state. The judge said that returning the prisoners to Arkansas would make his state involved in what he called "institutes of terror, horror, and despicable evil," which he compared to Nazi concentration camps.

In 1966, around the time of the Oregon judge's ruling, the ratio of staff to inmates at the Arkansas penal farms was one staff member for every sixty-five inmates. In contrast, the national average at the time was about one prison staff member for every seven inmates. The state wasn't the only one profiting from the farm; private operators controlled some of its industries and made high profits. For example, the doctor who ran the farm's for-profit blood bank earned between $130,000 and $150,000 per year from inmate donations that he sold to hospitals.

Because of this severe shortage of staff, authorities at the penal farms relied on armed inmates, known as "trusties" or "riders," to guard the convicts while they worked. Under the trusties' control, prisoners worked ten to fourteen hours per day, six days a week. Arkansas was, at the time, the only state where prison officials could still whip convicts.

Violent deaths were common on the Arkansas prison farms. An investigation started by Governor Orval Faubus during a heated 1966 election revealed ongoing abuses. When the chairman of the Arkansas legislature's prison committee was asked about the allegations, he replied, "Arkansas has the best prison system in the United States." Only later, after a federal court stepped in, did reforms begin at the Arkansas prison camps.

Modern Developments in U.S. Prisons

Today, the U.S. prison system continues to evolve. There's a focus on safety and security, including understanding and preventing gang activity inside prisons. This means stopping illegal money transactions, extortion, and corruption, as these can lead to more violence.

Prisons are also looking at how to help people re-enter society, especially those involved with gangs. There's a recognition that prisons can sometimes become places where gang activity thrives. All state prisons deal with gangs in some way, through associations, recruitment, force, or extortion.

There's a need for reform at all levels. This includes focusing on individuals to prevent new gang recruitment, ensuring law enforcement is not corrupt, and looking into individuals with gang-related tattoos and their associates. Regular inspections of prison operations and cleansing of bad practices are important. Officials are encouraged to look for trends, try new ideas, be curious, test limits, and be aware of how organized crime changes.

For-profit privately owned prisons often don't pay prisoners who work a fair amount, and basic necessities are overpriced and undersupplied. Some suggest that inmates should be assigned environmental work with reasonable pay, which could also reduce the need for taxpayer money. There's a demand for more security, guards, camera monitoring, unpredictable schedules, and modern prison architecture to prevent problems. Inmates are entitled to protection from gang recruitment, violence, and physical harm.

Images for kids

-

Former workhouse in Nantwich, dating from 1780

-

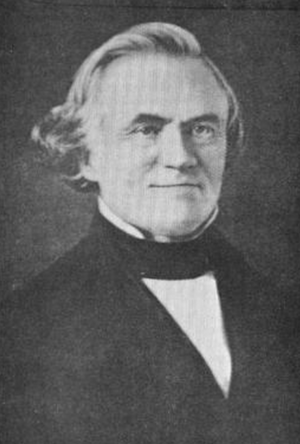

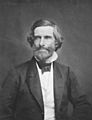

Cesare Beccaria, Italian rationalist penal reformer and author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764).

-

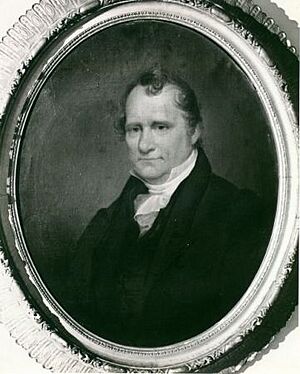

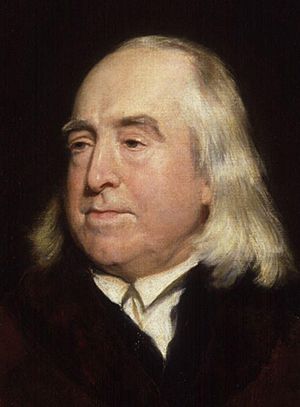

Jeremy Bentham, English rationalist penal reformer and designer of the Panopticon.

-

Richard Hakluyt, promoter of large-scale English settlement in the Jamestown Colony by convicts, as depicted in stained glass in the west window of the south transept of Bristol Cathedral.

-

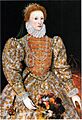

Under Queen Elizabeth I, English vagrancy laws began increasingly to provide for penal transportation as a substitute for capital sentences.

-

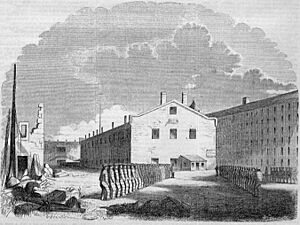

The Old Newgate Prison in London was one of many detention centers that facilitated the convict trade between England and its American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries.

-

Present-day exterior shot of the gate at Eastern State Penitentiary, birthplace of the "Pennsylvania (or Separate) System" of prison governance.

-

Present-day photograph of a typical cell at the Eastern State Penitentiary, where the "Pennsylvania (or Separate) System" was first practiced, in restored condition.

-

Samuel Gridley Howe, antebellum American reformer and advocate for the "Pennsylvania (or Separate) System" of prison governance.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |