History of roads in Ireland facts for kids

Ireland has a long history of roads and pathways, connecting towns and helping people trade goods since ancient times. Today, the country has a huge network of public roads that link every part of the island.

Contents

Ireland's First Roads: Ancient Paths

The very first paths in Ireland were made in prehistoric times. Some of these old paths later became wider roads that wheeled vehicles could use. Many smaller roads in Ireland today might have started as these ancient paths. These "evolved roads" changed over many, many years, often from tracks used thousands of years ago. They usually followed the natural shape of the land, like going along the tops of hills or crossing rivers at shallow spots called fording points.

There isn't much proof that big roads were built in Ireland during the Stone Age. However, a very large oval henge (a circular monument) from around 2500 BC (the Neolithic period) might have had an old road linked to it. This henge was found at the Hill of Tara archaeological site. It's unlikely that any road from this time was used for regular transport.

Wooden Trackways and Early Wheels

When people were building a new road in County Longford, they found many wooden trackways and platforms. These were built from the Neolithic period (around 4000 BC) to the early medieval period (around AD 400-790).

Wheeled vehicles with solid wooden wheels arrived in northern Europe around 2000 BC. An old wooden wheel was found next to a wooden trackway in the Netherlands. This suggests that building roads became important when wheeled carts were introduced.

An early Bronze Age trackway, from just after 2000 BC, was found in County Offaly. It might have been made for disc-wheeled vehicles. Another wooden trackway, about 1 meter wide, was found in County Leitrim. It was built around 1500 BC, but it was too narrow for wheeled vehicles. Similar wooden trackways were found all over Ireland from the Late Bronze Age. One in County Antrim was 2 meters wide and made of oak, suggesting it was for carts or wagons.

Stone Roads and Bogs

Archaeologists have found some stone roads built in the Irish Iron Age. Ireland was never part of the Roman Empire, so there were no Roman roads here. However, a 22-kilometer stone road, part of a defense system, was found in Munster. This shows that "Roman methods of road construction were known in Ireland."

Most surfaced paths from this time were made of wood. They helped people travel through bogs. These special roads, called Togher (Irish: tóchar) roads, were like causeways built through wet boggy areas. They were found in many parts of the country.

Roads in Medieval Ireland

Even though old Irish laws described different types of roads, and old records mentioned major highways, Ireland never had a road network as developed as the Roman Empire's. The roads stayed pretty basic through the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods. It wasn't until the 18th century that a big system of roads suitable for long-distance travel was built. These new roads were wider and straighter. Many of them are still part of Ireland's main road network today.

Road building continued into the early 19th century. Then, railways became the main way to travel and transport goods from the 1840s onwards. Later, with the invention of the internal combustion engine and cars, traffic on roads increased. Roads were then improved and developed even more. Ireland's roads have continued to grow and get better right up to today.

Five Ancient Highways to Tara

According to an old Irish record called the Annals of the Four Masters, in AD 123, there were five main highways (Irish: slighe) leading to Tara. The record says these roads were "discovered" when a famous king, Conn of the Hundred Battles, was born.

The five roads were:

- Slighe Asail: Went west towards Lough Owel in County Westmeath.

- Slighe Midluachra: Went north through Slane and Moyry Pass to Emain Macha, ending at Dunseverick on the north coast of County Antrim.

- Slighe Cualann: Went south-east through Dublin, crossing the River Liffey on a wooden bridge.

- Slighe Dala: Went towards Ossory in County Kilkenny.

- Slighe Mhór ('Great Highway'): Followed the Esker Riada towards County Galway.

In reality, the old road system didn't spread out from Tara, but more likely from Dublin.

What Were Medieval Roads Like?

Unlike Roman roads, these medieval Irish routes were not always clear, paved paths. They were more like "rights of way" or traditional routes. Roads often followed the easiest path, twisting and turning to avoid wet or difficult areas. If there was a hill or a tough spot, many different tracks might form, with travelers choosing the easiest one. Routes could also change with the seasons, depending on the weather.

Words for Roads in Old Irish Law

Old Irish law books described five types of roads:

- Highway (slige): Wide enough for two chariots to pass without one having to move aside.

- Local road (rout or ród): Wide enough for one chariot and two riders to pass side-by-side.

- Connecting road (lámraite): A smaller road linking two major roads.

- Side road (tógraite): Led to a forest or river. People could rent these roads and charge tolls for cattle.

- Cow road (bóthar): Had to be as wide as two cows, one standing normally and one sideways.

The word bóthar is now the most common word for "road" in modern Irish. Its smaller form, bóithrín, (or boreen in English) means a very narrow, country road.

Early Bridges

Before the Normans arrived, bridges in Ireland were not made of stone. They were built from timber, sometimes supported by natural rocks or man-made pillars. A wooden bridge was built across the Shannon at Killaloe in 1071. Some bridges were made of strong woven hurdles supported on piles. This type of bridge gave Dublin its Irish name: Baile Átha Cliath, meaning 'Town of the Hurdled Ford'.

The Esker Riada: An Ancient Highway

The Esker Riada (Irish: Eiscir Riada) is a natural system of ridges, called eskers. It stretches across the narrowest part of Ireland, between Dublin and Galway. Because this slightly higher ground offered a path through the bogs of central Ireland, it has been a major highway connecting the east and west of Ireland since ancient times. Its old Irish name was An Slighe Mhór, meaning ‘The Great Highway’.

Today, the route of the Dublin-Kinnegad-Galway road (the N4, M4, N6, M6) roughly follows the Esker Riada. The Esker Riada also formed an ancient dividing line in Ireland: Leath Cuinn (‘Conn’s Half’) to the north, and Leath Mogha (‘Mogha’s Half’) to the south.

Travel in Later Medieval Times

In later medieval Ireland, roads were not the most important way to travel. Most long journeys between towns happened by sea or on rivers. Road conditions were often bad and dangerous, making travel slow and uncomfortable. An old writer, Giraldus Cambrensis, described 12th-century Ireland as a "desert land [meaning sparsely populated], without roads, but well watered."

Traveling by sea was much faster than by land. It was also easier to move large amounts of goods by ship. A ship could travel 96 to 145 kilometers per day, while a traveler on land might only cover 40 kilometers. Most paths were not good for wheeled vehicles, so people used pack animals to carry goods.

Some efforts were made to improve routes during the Tudor period. For example, people tried to clear rivers of obstacles and built more roads and bridges for military reasons. But these efforts were not very organized. In 1558, it took a government official two days to travel about 100 kilometers from Limerick to Galway.

Roads from the 17th to 19th Centuries

17th Century Road Challenges

In 1614, the Irish Parliament passed the Highways Act. This law required local parishes to maintain roads within their areas that led to market towns. The Act encouraged improvements to existing roads and building new ones, especially in the Ulster Plantation area. The fact that local parishes were in charge of road maintenance is partly why Ireland has so many small roads today.

Travelers in the 17th century faced many difficulties on Irish roads. One military officer traveling in 1602 said he "lost our way and were compelled to go on foot, leading our horses through bogs and marshes." The journey took two days. Another traveler in 1619-1620 described his horse sinking into boggy roads and his saddles getting ruined. He often had to swim his horse across streams, which was dangerous. These stories show that most roads and tracks at this time were not suitable for any kind of wheeled vehicle.

18th Century Road Improvements

By the 18th century, Ireland had a much better road network. Important roads were shown on maps, like Herman Moll's "New Map of Ireland" from 1714.

In 1765, new laws gave county Grand Juries the power to spend money on repairing old roads or building new ones. This system of funding roads, called the presentment system, lasted until 1898. It was very successful in giving Ireland a good system of public roads. English travelers like Arthur Young were impressed, saying Ireland had "got suddenly so much the start of us in the article of roads."

New roads had to be at least 9.14 meters wide between fences, with a 4.27-meter wide gravel surface. In 1777, regular maintenance contracts were set up. Detailed maps of Ireland's roads were published in 1778 and 1783.

Turnpike Roads and Tolls

From 1729, a network of turnpike roads was built. These roads charged tolls (a fee to use them). A "turnpike" was a gate across the road that opened when you paid the toll. Most turnpike roads were about 30 miles long. Routes to and from Dublin were developed first, and the network spread across the country.

Turnpikes operated until 1858. They became less popular as the railway network grew. Turnpike roads were not as widely used in Ireland as in England because there were many toll-free roads built under the presentment system. If a turnpike road didn't have much traffic, it didn't earn enough money, and maintenance was neglected.

However, in the early 1800s, contracts for mail coaches increased income, and the quality of turnpike roads improved. Horse-drawn carriage services, like the Bianconi coaches, also used turnpike roads. By 1820, Ireland had about 2,400 kilometers of turnpike roads, but this dropped to 480 kilometers by 1856. By 1858, all turnpike roads in Ireland were gone.

You can still see signs of turnpike roads today, like milestones and old toll-booths. Some Irish place names also remember the turnpike system, like Dublin Pike and Kerry Pike in Cork.

19th Century Road Expansion

Even though Ireland's road network was good by 1800, many remote areas, especially in the west, still didn't have good roads. In 1822, the government offered money for road building projects, and roads were built in western counties. New roads brought big changes to some areas. For example, Belmullet had only three houses when the first wheeled vehicle arrived in 1823. Ten years later, it had 185 houses, shops, and hotels!

In 1831, the Board of Public Works (Ireland) was created. It was in charge of many public duties, including building roads and bridges. By 1848, it was responsible for about 1,600 kilometers of roads. Many major roads in the north of Ireland were improved by the Board. New routes were also built, like the coast road between Larne and Ballycastle in County Antrim.

Special roads were built in Munster to help the butter trade, which was centered in Cork. The first "butter road" was built in 1748. One of these routes, opened in 1829, cut the distance between Cork and Listowel from 102 miles to 66 miles.

In other areas, like County Wexford and County Wicklow, military roads were built. These helped the British military control remote areas. The Military Road through County Wicklow was started in 1800 and finished in 1809. The R115 is part of this historic road.

Many roads built in the 18th and 19th centuries became the foundation for today's National Primary, National Secondary, and Regional roads in the Republic of Ireland. They also formed the main roads in Northern Ireland.

Roads from the 20th Century Onwards

From the mid-1800s, railways were the main way to travel on land. This continued until the first half of the 20th century. Then, cars, buses, and trucks gradually took over as the most important way to get around.

The 20th century brought a new focus on roads as the main way to transport people and goods. With more and more cars on the road, urgent improvements were needed to make roads suitable for the "automobile age."

In 1909, a Road Board was set up to improve roads. It was funded by a tax on motor fuel and car licenses, called the Road Fund. Road surfaces were improved, and roads were widened and straightened. The Road Board was later replaced by the Ministry of Transport. After the Irish Free State was formed in 1922, the Minister for Local Government took over responsibility for roads.

Roads in Northern Ireland and the Republic

Since the partition of Ireland in 1921-1922, the public road networks in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have developed differently. Responsibility for roads in Northern Ireland went to the Stormont government.

There are several differences between roads in the North and South:

- Road Classification: Roads in the Republic are signed with M (for motorways), N (for national roads), R (for regional roads), and L (for local roads). Roads in Northern Ireland are signed with M (for motorways), A (for A-class roads), and B (for B-class roads).

- Distances and Speed Limits: Signs in Northern Ireland show distances in miles, and speed limits are in miles per hour (mph). In the Republic, signs show distances in kilometers, and speed limits are in kilometers per hour (km/h). Metric speed limits were introduced in the Republic in 2005.

- Language on Signs: The Republic's road signs are bilingual, using both Irish and English. Signs in Northern Ireland are in English only.

- Warning Signs: Northern Ireland uses warning signs similar to those in Great Britain, which are black symbols on a white background with a red border, in a triangle shape. Since 1956, the Republic of Ireland has used diamond-shaped warning signs, with black symbols on a yellow (or reddish-orange for temporary) background, similar to signs in the US and Australia.

Because of these differences, you'll see signs at the border warning drivers about the change to either metric or imperial systems. Some signs also show route numbers used in the other country.

Road Improvements: 1920s to 1950s

In 1922, the Irish Free State inherited a road network that needed major improvements. Most road surfaces were made of crushed stone without tar. The Local Government Act, 1925 made local county councils responsible for building and maintaining main roads and county roads.

Money from the Road Fund was given to local councils to improve and maintain roads. By the 1930s, the surfaces of main roads were improved, and attention turned to widening and straightening them. Most main roads now had tarmac surfaces. Road improvements stopped during World War II because tar and bitumen were hard to get. After the war, roads were repaired and improved again.

From Trunk Roads to National Roads

Ireland has had different ways of classifying roads since 1925. Before the current system, roads were called T (Trunk Roads), L (Link Roads), and unclassified roads. This system was in place by the 1950s. However, the original Trunk and Link road system was never formally made law.

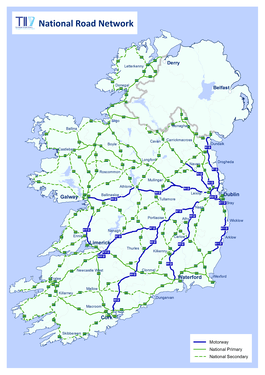

Ireland's Current Road System

The current system of road classification began in the late 1960s. In 1969, a study suggested classifying roads into national roads (primary and secondary), regional roads, and county roads. This system was later adopted.

In 1974, the Local Government (Roads and Motorways) Act allowed roads to be called motorways or national roads. The first national roads were officially named on June 1, 1977. This included 25 National Primary routes (N1-N25) and 33 National Secondary routes (N51-N83).

The change to the new system was slow. Maps from the late 1970s still showed a mix of old Trunk and Link road numbers and new National route numbers. Many of the remaining classified roads became Regional roads. Other roads became Local roads.

The National Roads Authority (NRA) was set up in 1994. Its main job is to "secure the provision of a safe and efficient network of national roads." This means they are responsible for planning, building, and maintaining motorways and national roads. They also put up traffic signs on national roads. Many large road projects are built through public-private partnerships (PPP), where private companies help fund and build the roads.

Road Improvements: 1980s and 1990s

In 1979, a plan called "Road Development Plan for the 1980s" was published. Its main goals were:

- To create a good system of roads connecting major towns, seaports, and airports.

- To make sure national roads had at least two lanes, with higher standards for some sections.

- To build bypasses around towns on national routes.

- To build new river crossings, ring roads, and relief routes in cities.

The National Development Plan (1989–1993) set out a program of road improvements. It included 34 major projects to build dual carriageways or motorways on 290 kilometers of national primary routes. Another 290 kilometers were to be upgraded to wide single carriageway standard. By the end of 1993, 35% of the national road network was "adequate or improved."

Some changes were made to the national road network in the 1980s and 1990s. New national secondary roads were added, and some roads were reclassified. For example, the N27, N28, N29, and N31 became national primary roads.

Road Improvements: 2000-2010

The 2000-2006 National Development Plan (NDP) set new goals for Ireland's national road network. Several routes, called Major Inter-Urban routes, were chosen to be upgraded to motorway or high-quality dual carriageway standard. These routes were completed by December 2010. The plan aimed for:

- Developing five major routes (Dublin to Dundalk, Dublin to Galway, Dublin to Cork, Dublin to Limerick, Dublin to Waterford) to motorway standard.

- Major improvements on other national primary routes.

- Finishing the M50 motorway and the Dublin Port Tunnel.

- Improving national secondary routes important for economic growth.

All these goals were met by December 2010. The M50 was finished in 2005 and upgraded between 2006 and 2010. The Dublin Port Tunnel opened in 2007. The major inter-urban routes were also completed.

As of December 2015, Ireland had a total of 5,306 kilometers of national roads. This included 2,649 kilometers of national primary routes (like motorways) and 2,657 kilometers of national secondary routes. The total length of the national road network changes each year due to new roads opening, old routes being replaced, and changes in road classification.

Besides national roads, Ireland also has many other public roads: 11,630 kilometers of regional roads and 78,972 kilometers of local roads.

Motorways in the Republic of Ireland

The most recent big change to Ireland's road network has been building motorways (Irish: mótarbhealach). The first motorway section in Ireland was the M7 Naas bypass, which opened in 1983. Several major routes between Dublin and other cities have been upgraded to motorway standard. Since December 2010, all motorways in Ireland are part of, or form, national primary roads.

There was a lot of motorway and dual carriageway construction between 2000 and 2010. By the end of 2010, there were a total of 916 kilometers of motorway, high-quality dual carriageway, and 2+2 roads. This was about 45% of the national primary route network.

In 2007, it was announced that about 800 kilometers of roads would become motorways. This included roads already open, under construction, or planned. Another new motorway, the M20, is being planned as the main route between Cork and Limerick.

By 2020, Ireland will have about 1,200 kilometers of motorway.

| Motorway number | Estimated/actual length | Corridor |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | 80 km | Dublin - Dundalk |

| M2 | 13 km | Dublin - Ashbourne |

| M3 | 49 km | Dublin - Navan |

| M4 | 55 km | Lucan - Mullingar |

| M6 | 144 km | Kinnegad - Galway |

| M7 | 175 km | Dublin - Limerick |

| M8 | 155 km | Portlaoise - Cork |

| M9 | 116.5 km | Naas - Waterford |

| M11 | 36 km | Dublin - Wexford |

| M17 | 25.5 km | Galway - Tuam |

| M18 | 60.8 km | Shannon - Galway |

| M20 | Approx 95 km | Cork - Limerick |

| M50 | 45.55 km | Dublin Orbital |

| Total | 1200 km | National motorway network. |

While many people welcome new motorways, some projects have caused controversy. For example, the building of the M3 motorway through the important archaeological area of Tara-Skryne valley led to protests. Many people, including the Director of the National Museum of Ireland, called for the protection of the landscape. The Smithsonian Institution in the US even put the Hill of Tara archaeological site on its list of endangered cultural treasures because of the M3's construction.

Images for kids

-

Herman Moll 1732 map showing the principal roads

-

Construction of dual-carriageway on A1 at Cloghogue Roundabout, Newry.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |