History of the Russian Federation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Russian Federation

Российская Федерация

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–present | |||||||||

|

Top: Emblem

(1992–93) Bottom: Coat of arms (1993–) |

|||||||||

|

Anthem:

Патриотическая песня Patrioticheskaya pesnya "The Patriotic Song" (1991–2000) Государственный гимн Российской Федерации Gosudarstvennyy gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii "State Anthem of the Russian Federation" (2000–present) |

|||||||||

Russian territory since the 2022 annexation of Ukrainian territory on the globe, with unrecognised territory shown in light green.

|

|||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

Moscow 55°45′N 37°37′E / 55.750°N 37.617°E |

||||||||

| Official language and national language |

Russian | ||||||||

| Recognised national languages | See Languages of Russia | ||||||||

| Ethnic groups

(2010)

|

|||||||||

| Religion

(2017)

|

|

||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Russian | ||||||||

| Government | Federal presidential republic (1991–1992) Federal semi-presidential republic (1992–1993) under rule by decree (Sep–Dec 1993) Federal semi-presidential constitutional republic (1993–present) under an authoritarian dictatorship (2014–present) |

||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1991–1999

|

Boris Yeltsin | ||||||||

|

• 1999–2008

|

Vladimir Putin | ||||||||

|

• 2008–2012

|

Dmitry Medvedev | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

|

• 1991–1992

|

Boris Yeltsin (first) | ||||||||

|

• 2020–present

|

Mikhail Mishustin (current) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet (1991–1993) Constitutional Conference (Oct–Dec 1993) Federal Assembly (1993–present) |

||||||||

| Soviet of Nationalities (1991–1993) Federation Council (1993–present) |

|||||||||

| Soviet of the Republic (1991–1993) State Duma (1993–present) |

|||||||||

| Independence

from the Soviet Union

|

|||||||||

|

• RSFSR sovereignty

|

12 June 1990 | ||||||||

|

• Yeltsin inaugurated

|

10 July 1991 | ||||||||

|

• Renamed

|

25 December 1991 | ||||||||

| 26 December 1991 | |||||||||

|

• Current constitution

|

12 December 1993 | ||||||||

|

• Second Chechen War

|

7 August 1999 – 30 April 2000 | ||||||||

| 8 December 1999 | |||||||||

| 7–12 August 2008 | |||||||||

| 18 March 2014 | |||||||||

|

• Last amendments

|

4 July 2020 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

|

• Total

|

17,098,246 km2 (6,601,670 sq mi)17,125,200 km2 (including Crimea) (1st) | ||||||||

|

• Water (%)

|

13 (including swamps) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

|

• 2022 estimate

|

|

||||||||

|

• Density

|

8.4/km2 (21.8/sq mi) (181st) | ||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2021 estimate | ||||||||

|

• Total

|

|||||||||

|

• Per capita

|

|||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate | ||||||||

|

• Total

|

|||||||||

|

• Per capita

|

|||||||||

| Gini (2018) | ▼ 36.0 medium · 98th |

||||||||

| HDI (2019) | very high · 52nd |

||||||||

| Currency | Russian ruble (₽) (RUB) | ||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+2 to +12 | ||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||

| Calling code | +7 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | RU | ||||||||

| Internet TLD |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Russia | ||||||||

The modern history of Russia began when the Russian Republic, part of the Soviet Union, started gaining more freedom. This happened as the USSR was breaking apart between 1988 and 1991. Russia declared itself sovereign in June 1990. A year later, Boris Yeltsin became its first elected President.

The Russian SFSR was the biggest part of the Soviet Union. It made up over 60% of the USSR's economy and more than half of its people. Russians were also very important in the Soviet military and the Communist Party. Because of this, Russia was seen as the main country taking over from the USSR. It took on the USSR's permanent spot and veto power in the United Nations Security Council.

Before the Soviet Union broke up, Boris Yeltsin was elected President of the Russian SFSR in June 1991. This was the first time a Russian president was chosen by direct vote. This meant he would lead Russia after the USSR dissolved. There was a lot of political tension as Soviet and Russian leaders struggled for power. This led to the August 1991 coup attempt, where the Soviet military tried to remove Mikhail Gorbachev. The coup failed, but it made the Soviet Union even more unstable.

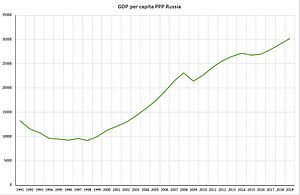

By October 1991, the USSR was about to collapse. Yeltsin announced big changes for Russia, including "shock therapy" to bring in capitalism. This caused a long economic recession. The average income per person didn't return to 1991 levels until the mid-2000s. After Yeltsin left office in 1999, Vladimir Putin became the main political leader, serving as either President or Prime Minister. Russia's economy has improved a lot under Putin.

Contents

Economic Changes in Russia

Introducing "Shock Therapy"

"Shock therapy" was a plan for fast economic changes. It was designed by Yeltsin's deputy prime minister, Yegor Gaidar. This idea was first used in Bolivia to fight high inflation. After some success there, it was brought to Poland and then to Russia.

One part of "shock therapy" was lifting price controls. This led to very high inflation, meaning prices went up very quickly. This almost bankrupted many Russian industries.

Selling State-Owned Businesses

After the Soviet Union ended, the new Russian government had to manage many state-owned businesses. The goal was to turn these businesses into profitable companies that didn't need government money to survive. This process was called Privatization.

To sell these businesses quickly and get public support, the government used a system of free vouchers. People received these vouchers, which they could use to buy shares in companies.

Later, in 1995, the government needed money for the 1996 presidential elections. They used a "loans-for-share" plan. Under this plan, some of Russia's biggest state industries were leased to commercial banks. The banks lent money to the government. However, these auctions were often unfair, and the businesses were sold at very low prices to a small group of powerful business people.

This privatization helped a small group of wealthy business leaders and "New Russians" gain a lot of money. Many of these people were in the natural gas and oil industries.

Challenges to Economic Reform

Russia faced many unique problems during its change from the Soviet system. These included changing its political system, restructuring its economy, and redrawing its borders. These changes were hard for Russia.

One big problem was the Soviet Union's huge spending on the Cold War. In the late 1980s, a quarter of the Soviet economy was spent on defense. Many adults worked in military factories. This made Russian industries less competitive when they moved to a market economy. When the Cold War ended, military spending was cut. It was hard for factories to change from making military equipment to making everyday goods.

Another problem was that many Russian regions depended on just one industry or one big factory. When the Soviet Union broke up, economic connections were cut. Production across the country dropped by more than half. Many cities had only one large factory. This led to huge unemployment when these factories struggled.

Also, Russia didn't have a strong system for social support like welfare from the USSR. Companies used to provide housing, healthcare, and education for their workers. When companies struggled, these services were lost. Local governments didn't have the money or systems to take over.

Finally, many people in Russia were not ready for a market economy. Soviet workers and managers were good at following plans, but not at taking risks or focusing on profits. They had little experience with decision-making in a market system. This made it hard to adapt to the new economic rules.

Economic Hardship and Recovery

After the first big changes, Russia's economy went into a deep depression in the mid-1990s. This was due to problems with the reforms and low global prices for goods. The Great Depression in the United States was less severe than Russia's economic decline in terms9 of total economic output.

In 1995, only about 3% of workers were officially unemployed. But many more worked part-time or were on forced leave. Millions of Russians went to work but were not paid. Some were paid with goods instead of money. For example, car factory workers might get paid in car parts.

By 1997, about one in four Russian workers, nearly 20 million people, were not paid for months. Many people had to find other ways to survive, like growing food or selling things on the street.

The economic problems led to a big increase in poverty and economic inequality. In the late Soviet era, only 1.5% of people lived in poverty. By mid-1993, between 39% and 49% of the population was poor. Average incomes fell even more by 1998.

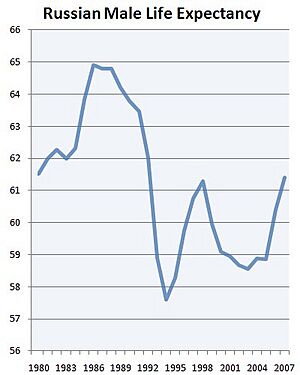

Public health also got worse. Birth rates dropped, and life expectancy for men fell from 64 years in 1990 to 57 years by 1994. While stores had more goods, most Russians couldn't afford to buy them because their incomes were so low.

Political Challenges and Crises

The 1993 Constitutional Crisis

The struggle for power in Russia after the Soviet Union's collapse led to a political crisis in 1993. President Yeltsin wanted fast privatization. The parliament, called the Supreme Soviet, opposed him. On September 21, Yeltsin dissolved the parliament, which was against the current constitution. He called for new elections and a vote on a new constitution.

The parliament then declared Yeltsin removed from office. They appointed Aleksandr Rutskoy as acting president. Tensions grew quickly. On October 4, Yeltsin ordered special forces and army units to storm the parliament building, known as the "White House." Tanks were used against the parliament's defenders. Rutskoy and other supporters surrendered and were arrested. The official count was 147 dead and 437 wounded.

This event ended the period of political change. A new constitution was approved in December 1993. It gave the president strong powers. Radical privatization continued. The old parliamentary leaders were released in February 1994, but they no longer played a public role in politics.

The First Chechen War

In 1994, Yeltsin sent 40,000 troops to Chechnya to stop it from leaving Russia. The Chechens, who are mostly Muslim, had a long history of resisting Russia. Dzhokhar Dudayev, Chechnya's leader, declared independence in 1991.

Russia did not recognize Chechnya's independence. In 1994, the Russian Armed Forces invaded. They faced strong resistance. In January 1995, the Russian army attacked the Chechen capital, Grozny. About 25,000 Chechen civilians died from air raids and artillery fire. Russian forces used heavy artillery and air strikes. However, Chechen forces took many Russian hostages and caused big losses for the Russian troops.

The Russians finally took control of Grozny in February 1995 after heavy fighting. In August 1996, Yeltsin agreed to a ceasefire with Chechen leaders. A peace treaty was signed in May 1997. However, the conflict started again in 1999. This time, Vladimir Putin led the effort to crush the rebellion.

The 1996 Presidential Election

The first round of voting was on June 16, 1996. Yeltsin won 35% of the vote, and Gennady Zyuganov won 32%. Since no candidate got more than half the votes, Yeltsin and Zyuganov went to a second round. Yeltsin gained support by appointing Aleksandr Lebed, a popular former general, to a top security job.

In the second round on July 3, Yeltsin won with 53.8% of the vote. Zyuganov received 40.3%. Yeltsin had promised to change his unpopular economic policies and increase public spending. However, within a month of his election, he canceled almost all of these promises. After the election, Yeltsin's health became very poor. Many of his duties were handled by his advisers.

The 1998 Financial Crisis

The global economic downturn of 1998 made Russia's economic problems worse. This crisis started with the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Countries that relied on exporting raw materials like oil were hit hard. Oil, natural gas, metals, and timber made up over 80% of Russia's exports. This made Russia vulnerable to changes in world prices. Oil was also a major source of government income.

The value of the Russian currency, the ruble, fell sharply. Many people avoided paying taxes, which reduced government income even more. Soon, the government could not pay its huge loans. It also couldn't pay its employees on time. Workers were often paid with goods instead of money. Coal miners were especially affected. They blocked parts of the Trans-Siberian railroad to protest.

In March, Yeltsin suddenly fired Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin. He appointed Sergei Kiriyenko, a young energy minister, as acting prime minister. The Duma (parliament) rejected Kiriyenko twice. Yeltsin threatened to dissolve the legislature, and the Duma finally approved Kiriyenko in April.

Kiriyenko tried to stop the ruble's fall by raising interest rates very high. But investors were already pulling money out of Russia due to the Asian crisis and low oil prices. By mid-1998, it was clear Russia needed help from the IMF. The IMF approved a $22.6 billion emergency loan in July.

Despite the loan, Russia's interest payments were still higher than its tax revenues. Investors continued to leave Russia. On August 17, Kiriyenko's government had to stop payments on Russia's foreign debt for 90 days. They also had to devalue the ruble. The ruble fell very quickly as Russians rushed to buy dollars. Many Russian banks were destroyed. Foreign investment left the country, and there was a huge flight of money from Russia.

Political Impact of the Crisis

The financial crisis caused a political crisis. Yeltsin's support was disappearing, and the parliament's opposition grew stronger. On August 23, Yeltsin fired Kiriyenko. He wanted Chernomyrdin back as prime minister. But the legislature refused to approve Chernomyrdin.

Yeltsin's power was clearly weakening. He nominated Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov instead. On September 11, the Duma overwhelmingly approved Primakov. Primakov's appointment brought political stability. He was seen as a compromise candidate who could unite different groups. Primakov promised to pay back wages and pensions first. He also invited members of the main parliamentary groups into his government.

On October 7, Communists and trade unions held a nationwide strike. They called for President Yeltsin to resign. On October 9, Russia asked for international humanitarian aid, including food, because of a bad harvest.

Economic Recovery

Russia recovered from the August 1998 financial crash surprisingly fast. One big reason was that world oil prices rose quickly in 1999–2000. This meant Russia earned a lot more money from exports. Another reason was that Russian industries, like food processing, benefited from the ruble's devaluation. This made imported goods more expensive, so people bought more Russian products.

Also, much of Russia's economy used barter (trading goods) instead of money. So, the financial collapse had less impact on many producers. Finally, more cash flowed into the economy. As businesses paid back wages and taxes, people had more money to spend. This increased demand for Russian goods and services. For the first time in years, unemployment fell in 2000.

However, the country's political and social balance remains fragile. Power is still very much tied to individuals. The economy can still be affected if world oil prices fall sharply.

The Succession Crisis

Yevgeny Primakov did not stay as prime minister for long. Yeltsin became suspicious that Primakov was gaining too much power and popularity. He dismissed Primakov in May 1999, after only eight months. Yeltsin then named Sergei Stepashin, who had been head of the FSB (the successor to the KGB), to replace him. The Duma approved Stepashin easily.

Stepashin's time in office was even shorter. In August 1999, Yeltsin again suddenly dismissed the government. He named Vladimir Putin as his choice to lead the new government. Like Stepashin, Putin had a background in the secret police. Yeltsin even said he saw Putin as his successor for president. The Duma narrowly approved Putin.

When he was appointed, Putin was not very well known. But he quickly became popular, largely because of the Second Chechen War. Just days after Putin was named prime minister, Chechen forces fought the Russian army in Dagestan. In the next month, hundreds of people died in apartment building bombings in Moscow and other cities. Russian authorities blamed Chechen rebels. In response, the Russian army entered Chechnya in September 1999, starting the Second Chechen War. The Russian public supported the war, which made Putin very popular.

After political groups close to Putin did well in the December 1999 parliamentary elections, Yeltsin felt confident enough in Putin. He resigned from the presidency on December 31, 1999, six months early. This made Putin acting president. It gave Putin a big advantage for the presidential election on March 26, 2000, which he won. In February 2000, Russian troops entered Grozny, the Chechen capital. A week before the election, Putin flew to Chechnya on a fighter jet, claiming victory.

The Putin Era in Russia

Vladimir Putin became president at a good time. The ruble's value had fallen in 1998, which made people buy more Russian goods. Also, world oil prices were rising. During his first seven years as president, Russia's economy grew by 6.7% each year on average. Average incomes increased by 11% annually. The government also managed to cut 70% of its foreign debt.

On March 14, 2004, Putin was re-elected for a second term, winning 71% of the vote. In 2005, the National Priority Projects were launched. These projects aimed to improve Russia's healthcare, education, housing, and agriculture.

The Constitution of Russia prevented Putin from serving a third term in a row. First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was elected as his successor.

In 2008, Kosovo declared independence. This caused Russia's relationship with Western countries to get worse. Also in 2008, there was the 2008 South Ossetia war against Georgia. This war happened after Georgia tried to take control of the region of South Ossetia. Russian troops entered South Ossetia and pushed Georgian troops back. Russia then recognized the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Putin has said that two main achievements of his second time as Prime Minister were overcoming the world economic crisis and stabilizing Russia's population size. The population had been shrinking since the 1990s.

At a political meeting in Moscow on September 24, 2011, Medvedev suggested that Putin run for President again in March 2012. Putin accepted. On March 4, 2012, Putin won the 2012 Russian presidential election in the first round with 63.6% of the vote.

Russia's International Relations

After Russia became independent, its foreign policy changed. It moved away from its old communist ideas. Russia wanted to work with Western countries to solve global problems. It also asked for economic help from the West to support its internal reforms.

However, Russia's leaders faced challenges in defining new relationships with countries in Eastern Europe. Russia opposed the expansion of NATO into former Soviet bloc nations like the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary in 1997. It especially opposed NATO's expansion into Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia in 2004. In 1999, Russia opposed the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia for over two months. But it later joined NATO peacekeeping forces in the Balkans in June 1999.

Relations with the West have also been affected by Russia's ties with Belarus. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko is an authoritarian leader. He has not shown interest in Western-backed economic and political reforms. Instead, he has aligned his country with Russia. A union agreement between Russia and Belarus was formed on April 2, 1996. This union was strengthened over the years.

Under Putin, Russia has tried to build stronger ties with People's Republic of China. They signed the Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation. They also built the Trans-Siberian oil pipeline to meet China's growing energy needs. Putin also appeared with U.S. President George W. Bush, and they described each other as "friends."

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Federación de Rusia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Federación de Rusia para niños

- Economy of Russia

- Military history of the Russian Federation

- Politics of Russia

- Timeline of largest projects in the Russian economy

Images for kids

-

An abandoned radiotelescope facility near Nizhny Novgorod (2006).