History of the euro facts for kids

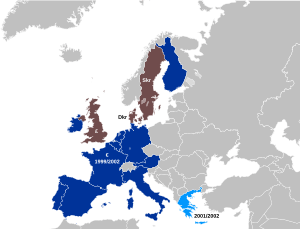

The euro is the money used by many countries in Europe. It started on 1 January 1999, but the idea of a single European money had been around since the 1960s. After many talks, the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1993. Its goal was to create an economic and monetary union (EMU) by 1999. Most EU countries joined, except for the UK and Denmark.

The euro first existed as digital money in 1999. Real euro notes and coins began to be used in 2002. It quickly replaced the old money in many countries. Over time, more countries joined the euro area. In 2009, the Lisbon Treaty officially set up the Eurogroup, which is like the euro's political leader, working with the European Central Bank.

Contents

How the Euro Was Created

Early Ideas for European Money

People thought about having a single money in Europe even before the European Communities were formed. For example, in 1929, a leader named Gustav Stresemann suggested a European currency. This was because Europe had many new countries after World War I, which made trade harder. People also remembered the Latin Monetary Union, which was a group of countries (like France, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland) that used similar coins. This union had broken apart after the First World War.

In 1969, the European Commission tried to create an economic and money union. They said countries needed to work together more on their money policies. Leaders met in The Hague in December 1969. They asked Pierre Werner, who was the Prime Minister of Luxembourg, to find a way to make currency exchange rates more stable. His report in 1970 suggested that countries should fix their money values to each other and allow money to move freely. But he didn't suggest one single currency or a central bank. An early attempt to control currency changes, called the snake in the tunnel, didn't work out.

In 1971, the US President Richard Nixon stopped linking the US dollar to gold. This caused problems for money systems around the world. But in March 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) was created. It fixed exchange rates to an accounting currency called the European Currency Unit (ECU). This helped keep exchange rates stable and control rising prices.

In 1986, the Single European Act made political cooperation official within the European Economic Community, including money matters. In 1988, leaders started planning how to work together on money. France, Italy, and the European Commission wanted a full money union with a central bank. But the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was against it.

Starting Again: The Delors Plan

Leaders asked Commission President Jacques Delors to lead a group of central bank governors. This group, called the Delors Committee, had to suggest a new plan for creating an economic and money union.

In 1989, the Delors report suggested a three-step plan to introduce the euro. It also included creating new groups like the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which would manage money policy. The first step began on 1 July 1990, when countries removed controls on money moving between them. Leaders agreed on the money union with the Maastricht Treaty, signed in 1992. They agreed to create a single currency by January 1999, though the UK would not join.

Getting countries to agree to the treaty was hard. Germany was worried about giving up its strong money, the German Mark. France only just approved the treaty. Denmark said no until they got to opt out of the money union, just like the UK. On 16 September 1992, known as Black Wednesday in the UK, the British pound sterling had to leave the fixed exchange rate system because its value fell quickly.

The Second Stage: Getting Ready

The second stage of the plan began in 1994 with the creation of the European Monetary Institute. This was a step towards the European Central Bank. Its first president was Alexandre Lamfalussy. After much discussion, in December 1995, the name euro was chosen for the new currency. They also agreed on 1 January 1999 as the launch date.

In 1997, the European Council agreed on the Stability and Growth Pact. This was to make sure countries managed their budgets well after the euro was created. A new exchange rate system (ERM II) was also set up to keep the euro stable with countries that hadn't joined yet. Then, in May 1998, 11 countries were chosen to join the euro from 1 January 1999. To join, countries had to meet strict rules. For example, their budget deficit had to be less than 3% of their GDP, and their debt less than 60% of GDP. They also needed low inflation and interest rates. Greece didn't meet these rules and couldn't join in 1999.

On 1 June 1998, the European Central Bank officially started. It got its full powers when the euro was created on 1 January 1999. The bank's first president was Wim Duisenberg. The exchange rates between the 11 national currencies and the euro were then set. These rates were fixed so that one ECU would equal one euro. All money conversions had to be done through the euro to avoid rounding problems.

The Euro is Born

Launch Day

The euro was launched as digital money (for things like bank transfers) at midnight on 1 January 1999. The old national currencies of the countries that joined (the eurozone) stopped existing on their own. Their exchange rates were locked, making them like smaller parts of the euro. The euro took over from the European Currency Unit (ECU).

The old notes and coins were still used as legal money until new euro notes and coins came out on 1 January 2002. From 1999, all government debts in eurozone countries were in euros.

The euro started at US$1.1686 on 31 December 1998. It went up on its first trading day, closing at about US$1.18. People quickly started using it. Traders were surprised how fast it replaced national currencies. For example, trading in the Deutsche Mark almost stopped as soon as markets opened. However, by the end of 1999, the euro had dropped to be worth the same as the dollar. This led to major countries (the G7) taking action to support the euro in 2001.

In 2000, Denmark voted on whether to give up their opt-out from the euro. They decided to keep their krone. This also made the UK delay its plans for a euro vote. The way the exchange rate for the Greek drachma was fixed was different. It was set several months before Greece joined, as the euro was already two years old.

Making the Coins and Notes

The designs for the new euro coins and notes were announced between 1996 and 1998. Production started on 11 May 1998. It was a huge job, taking three and a half years. In total, 7.4 billion notes and 38.2 billion coins were made ready for people and businesses by 1 January 2002. In some countries, the new coins had a 2002 date. But in Belgium, Finland, France, the Netherlands, and Spain, the coins had the date they were made (1999, 2000, or 2001). Small numbers of coins from Monaco, Vatican City, and San Marino were also made. These quickly became popular with collectors.

At the same time, people needed to learn about the new money. Posters showed the designs, which appeared on everything from playing cards to T-shirts. As a final step, on 15 December 2001, banks started giving out "euro starter kits". These were small plastic bags with a selection of new coins, usually worth 10 to 20 euros. They couldn't be used in shops until 1 January, when notes also became available.

Shops and government offices also had a big job. For things sold to the public, prices were often shown in both the old money and euros. Postage stamps often had both values too. Banks had a huge task, not just preparing for the new money, but also updating their computer systems. From 1999, all deposits and loans were technically in euros, but people still deposited and withdrew old money. Bank statements showed balances in both currencies from mid-2001.

From 1 December 2001, coins and notes were sent from secure places to big shops, then to smaller ones. Many people expected big problems on 1 January. A changeover like this, across twelve countries, had never been tried before.

Switching to the Euro

The new coins and notes were first used on the French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. The first official purchase with euros was for one kilogram of lychees there. In Frankfurt, the midnight moment at the ECB offices marked the official switch.

In Finland, the Central Bank opened at midnight for an hour so people could exchange money. In Athens, a huge euro pyramid decorated Syntagma Square. Other countries also celebrated. Paris's Pont Neuf bridge was lit up in EU colors. In the German town of Gifhorn, there was a symbolic funeral for the Deutsche Mark.

The plan for introducing the euro was mostly the same everywhere, except for Germany. Banks would exchange old money and ATMs would give out euros from 1 January. Shops would accept old money but only give change in euros. In Germany, the Deutsche Mark stopped being legal money on 1 January and had to be exchanged at banks.

Despite having lots of euros ready, people worried about chaos. In France, fears grew because postal workers threatened to strike. But the strike was settled. Bank workers also threatened to strike, but that was settled too.

In the end, the changeover went smoothly with few problems. By 2 January, ATMs in 7 countries and at least 90% in 4 others were giving out euros. Italy was the slowest, with only 85% of ATMs dispensing euros. People unexpectedly spent their old money instead of exchanging it at banks. This led to a temporary shortage of small euro change, and some shops gave change in old money.

Some businesses used the changeover to raise prices. A study in Germany found that prices went up, but people bought less. An Italian coffee shop that raised coffee prices by a third was ordered to pay money back to customers.

After the Big Switch

Countries could keep their old money as legal tender for two months, until 28 February 2002. The exact date when national currencies stopped being legal varied. In Germany, the Deutsche Mark stopped being legal on 31 December 2001. Most countries allowed their old money to be used for the full two months. Old money could be exchanged at commercial banks for a longer time, usually until 30 June 2002.

Even after these dates, national central banks continued to exchange old money for different periods. In Austria, Germany, Ireland, and Spain, they still exchange old money indefinitely. Coins from these four countries and Finland can still be exchanged. The first coins to become worthless were the Portuguese escudos, which lost their value after 31 December 2002. All banknotes from 1 January 2002 were valid until at least 2012.

In Germany, Deutsche Telekom changed 50,000 pay phones in 2005 to accept Deutsche Mark coins again, at least for a while. Callers could use DM coins, with one DM equal to one euro, which was almost double the usual rate.

In France, even in 2007, receipts still showed prices in both francs and euros. In other eurozone countries, this was no longer needed. As of 2008, some small shops in France still accepted franc notes.

The Euro Grows Stronger

After falling to US$0.8296 in October 2001, the euro soon got stronger. Its value last closed below $1.00 in September 2022. It reached its highest value against the US dollar at $1.5916 in July 2008. As its value grew against the pound sterling in the late 2000s, its use around the world increased quickly. The euro became more important, with its share of money held by central banks rising from almost 18% in 1999 to 25% in 2003. Alan Greenspan, a famous economist, said in 2007 that the eurozone had benefited from the euro's rise. He thought it was possible the euro could become as important or even more important than the US dollar in the future.

Public Support for the Euro

The graph below shows how much people supported the euro in each country between 2001 and 2006.

The Euro During Tough Times

The 2008 Financial Crisis

Because of the global financial crisis that started in 2007-2008, the eurozone faced its first official recession in late 2008. The EU had negative economic growth for several quarters. Even with the recession, Estonia joined the eurozone. Iceland even applied to join the EU and the euro, seeing it as a safe place for its money.

The Lisbon Treaty and Eurogroup

In 2009, the Lisbon Treaty officially recognized the Eurogroup. This is a meeting of finance ministers from euro countries, with an official president. Jean-Claude Juncker was president before and after this change. He wanted to make the group stronger and have more economic cooperation. The recession made people want stronger economic cooperation. However, Germany had been against strengthening the Eurogroup, fearing it would weaken the European Central Bank's independence.

Leaders of eurozone countries held a special meeting in Paris in October 2008 because of the financial crisis. They met as heads of state to create a plan to stabilize the European economy. Many important euro changes were agreed at these meetings.

Helping Countries in Need

Leaders created a plan to deal with the financial crisis. This plan involved billions of euros to prevent a financial collapse. They agreed on a bank rescue plan: governments would invest in banks to help them and guarantee loans between banks. Working together was very important to stop one country's problems from hurting others.

Even though some people worried the eurozone might break up in early 2009, the euro actually got stronger. The difference in borrowing costs between Germany and weaker economies decreased. Many people gave credit to the ECB for this, as it put €500 billion into banks. The euro became seen as a safe haven, meaning a safe place for money. Countries outside the euro, like Iceland, did worse than those inside.

Bailout Funds

However, when Greece faced a risk of not being able to pay its debts in late 2009-2010, eurozone leaders agreed to help countries that couldn't raise money. This was a big change from EU rules, which said countries shouldn't bail each other out. But with Greece struggling and other countries at risk, a temporary bailout plan was agreed. This plan created the "European Financial Stability Facility" (EFSF) to help keep Europe's finances stable. The crisis also led to calls for more economic cooperation.

In 2010, countries agreed on a plan for EU members to review each other's budgets before they went to their own parliaments. Each government would show their plans for growth, inflation, and spending. If a country had too much debt, it would be watched more closely. These plans would apply to all EU members. In June 2010, France agreed to support Germany's idea of taking away voting rights from members who broke the rules.

In late 2010 and early 2011, it was agreed to replace the temporary bailout funds with a permanent one called the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). This needed a change to the EU treaties. Meanwhile, to help Italy, the ECB started buying Italian bonds, just as it had done with Greece.

New Financial Rules

In March 2011, new rules were started to make the Stability and Growth Pact stronger. This meant automatically giving penalties if countries broke budget or debt rules. The Euro Plus Pact set out many reforms for the eurozone. The French and German governments also agreed to push for a "true economic government" with regular eurozone leader meetings and a tax on financial transactions.

The European Fiscal Union is an agreement about how countries manage their money together. It was agreed in December 2011 by eurozone countries and most other EU members. The agreement started on 1 January 2013 for the first 16 countries that approved it. By April 2014, all 25 countries that signed it had approved it.

More Countries Join the Euro

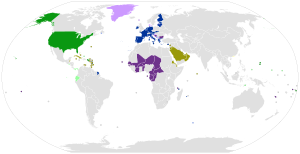

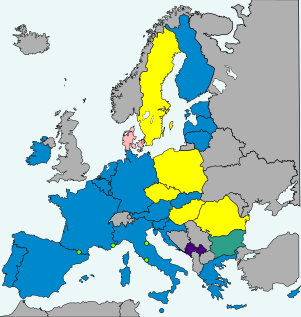

- European Union (EU) member states

- 20 in the eurozone 1 in ERM II, without opt-out (Bulgaria) 1 in ERM II, with an opt-out (Denmark) 5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member territories

- 4 using the euro with a monetary agreement (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City) 2 using the euro unilaterally (Kosovo and Montenegro)

Even though there were worries about the euro during the crisis, some newer EU countries from the 2004 expansion joined the currency. Slovenia, Malta, and Cyprus joined within the first two years of the recession. Slovakia followed in 2009. The three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—joined in 2011, 2014, and 2015. Eight years later, Croatia joined the eurozone in 2023.

Slovenia Joins

Slovenia was the first country to join the eurozone after the euro notes and coins were launched. It joined the ERM II system in 2004. In July 2006, the EU Council allowed Slovenia to join the euro area from 1 January 2007. This made it the first country from the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to use the euro. The euro replaced the Slovenian tolar on 1 January 2007. Unlike earlier launches, both cash and digital euro transactions started at the same time.

Cyprus Joins

Cyprus replaced the Cypriot pound with the euro on 1 January 2008. Cyprus officially asked to join the eurozone in February 2007. In May 2007, the European Commission and European Central Bank approved its plan to join in January 2008.

A campaign to tell people in Cyprus about the euro started in March 2007. In July 2007, the EU finance ministers confirmed the date. The exchange rate was fixed at 0.585274 Cypriot pounds for one euro. On 1 January 2008, the euro became the official money. The euro is used in the government-controlled parts of Cyprus, the UK's military bases there, and the UN Buffer Zone. The northern part of Cyprus still uses the new Turkish lira.

Malta Joins

Malta replaced the Maltese lira with the euro on 1 January 2008. The EU approved Malta's plan in May 2007. From that day, shops had to show prices in both old money and euros. The first Maltese euro coins were made in Paris. People could get "euro starter packs" with new coins from 1 December 2007. These were for businesses to fill their cash registers. Smaller "mini-kits" were available for the public from 10 December 2007. Old Maltese coins could be exchanged until February 2010.

Maltese citizens could get euro information from special "Euro Centres" in their towns. People trained about the euro changeover were there to help. In December 2007, as part of the celebrations, streets in Valletta were covered with carpets showing euro coin designs. New Year's Eve celebrations included fireworks near the Grand Harbour.

Slovakia Joins

Slovakia adopted the euro on 1 January 2009. The koruna had been part of the ERM II system since 2005. Its exchange rate was changed several times before being fixed in July 2008.

To help with the change, the National Bank of Slovakia announced its plan for taking old koruna notes and coins out of use. In April 2008, Slovakia officially asked to join the eurozone. The European Commission approved the request in May 2008.

Slovakia met all the rules to join the euro. Its inflation was low, and its budget deficit and government debt were within limits. Most people supported the switch, but many worried about prices going up. Three months after joining, 83% of Slovaks thought it was the right decision.

To promote the change, a "euromobile" drove around the countryside. An actor held quizzes about the euro, and winners got euro T-shirts, calculators, and chocolate coins. Euro starter kits were popular Christmas gifts in 2008. These coins were not legal until 1 January 2009. Shops that used the changeover to raise prices could be fined.

Baltic States Join

In 2010, Estonia got approval to join the euro on 1 January 2011. It became the first country from the former Soviet Union to use the euro. In 2013, Latvia got approval to join on 1 January 2014. On 23 July 2014, Lithuania became the last Baltic state to get permission to join the euro, which it did on 1 January 2015.

Croatia Joins

Croatia planned to adopt the euro after joining the EU on 1 July 2013. The country joined the ERM II on 10 July 2020. On 12 July 2022, the EU Council allowed Croatia to join the eurozone from 1 January 2023. The euro replaced the Croatian kuna on that date. The exchange rate was set at 7.5345 Croatian kuna for one euro. Like Slovenia, Croatia introduced cash and digital euro transactions at the same time. On the same day, Croatia also joined the Schengen Area.

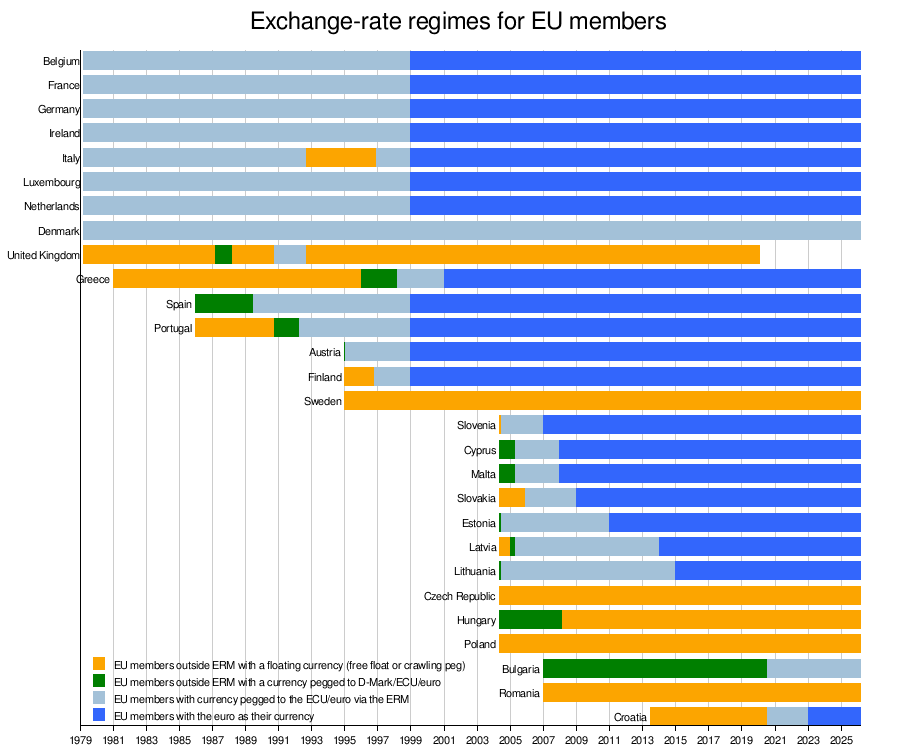

Eurozone Growth and Exchange Rates

The chart below shows how EU countries have managed their money exchange rates since the European Monetary System started in 1979. The euro replaced the ECU (European Currency Unit) in 1999. Before the euro, the Deutsche Mark was like a main currency for the ECU.

Sources: EC convergence reports 1996-2014, Italian lira, Spanish peseta, Portuguese escudo, Finnish markka, Greek drachma, Sterling

The eurozone started with 11 countries on 1 January 1999. Greece was the first country to join later, on 1 January 2001, even before euro notes and coins were physically used. Other countries that joined the EU in 2004 later joined the eurozone: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009), Estonia (2011), Latvia (2014), Lithuania (2015), and Croatia (2023).

All new EU members who joined after the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 must adopt the euro. But first, they need to meet five economic rules. One rule is that their exchange rate must be stable for at least two years as an ERM-member.

In 2011, a source said that the money union these new countries thought they were joining might change a lot. It could mean much closer financial, economic, and political cooperation. This might make them think the original promise to join was no longer valid. This could even lead to new votes on whether to adopt the euro.

Public Support for the Euro Over Time

| Member State or Candidate |

Joined Eurozone |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 59 | 68 | 72 | 75 | 72 | 67 | 68 | 73 | 65 | 67 | 60 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 66 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 64 | 68 | 63 | 58 | 65 | 66 | 65 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 63 | 62 | 69 | 62 | 68 | 69 | 67 | 70 | 73 | |

| 1999 | 75 | 72 | 82 | 81 | 85 | 81 | 83 | 89 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 85 | 84 | 82 | 84 | 82 | 83 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 82 | 80 | 75 | 69 | 76 | 74 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 79 | 77 | 76 | 78 | 81 | 82 | 84 | 92 | |

| N/A | 74 | 67 | 63 | 65 | 62 | 66 | 64 | 57 | 68 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 55 | 54 | 57 | 50 | 54 | 46 | 44 | 51 | 41 | 45 | 43 | 37 | 42 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 35 | 35 | 42 | |||||||

| 2023 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 59 | 63 | 68 | 66 | 65 | 63 | 59 | 67 | 67 | 64 | 63 | 62 | 52 | 61 | 57 | 53 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 54 | 52 | 51 | 43 | 46 | 40 | 45 | |||||||||

| 2008 | 65 | 59 | 53 | 46 | 46 | 43 | 50 | 46 | 58 | 58 | 67 | 63 | 57 | 63 | 55 | 55 | 52 | 48 | 47 | 44 | 53 | 51 | 44 | 49 | 53 | 52 | 60 | 67 | 69 | 74 | 74 | |||||||

| N/A | 56 | 60 | 63 | 60 | 57 | 60 | 60 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 51 | 55 | 36 | 41 | 28 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 33 | |||||||

| N/A | 40 | 47 | 52 | 55 | 53 | 52 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 53 | 54 | 52 | 51 | 51 | 53 | 53 | 42 | 43 | 41 | 29 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 29 | 34 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 30 | 30 | |

| 2011 | 46 | 55 | 59 | 53 | 48 | 49 | 54 | 54 | 56 | 58 | 31 | 63 | 57 | 63 | 71 | 64 | 71 | 69 | 73 | 76 | 80 | 83 | 83 | 82 | 78 | 81 | 83 | 84 | 88 | 85 | 89 | |||||||

| 1999 | 67 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 75 | 70 | 73 | 79 | 77 | 79 | 75 | 78 | 81 | 77 | 80 | 82 | 83 | 81 | 77 | 64 | 77 | 71 | 74 | 76 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 75 | 78 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 76 | 82 | 77 | |

| 1999 | 49 | 63 | 67 | 71 | 75 | 68 | 68 | 78 | 76 | 78 | 70 | 76 | 72 | 74 | 71 | 73 | 73 | 69 | 65 | 69 | 69 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 62 | 63 | 68 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 70 | 68 | 72 | 71 | 70 | 72 | 74 | |

| 1999 | 53 | 60 | 67 | 62 | 70 | 60 | 58 | 69 | 59 | 66 | 63 | 66 | 72 | 69 | 69 | 71 | 69 | 66 | 62 | 67 | 63 | 66 | 65 | 69 | 66 | 71 | 75 | 74 | 76 | 73 | 73 | 81 | 83 | 81 | 83 | 81 | 82 | |

| 2001 | 72 | 79 | 80 | 71 | 70 | 64 | 64 | 62 | 49 | 46 | 51 | 49 | 47 | 51 | 51 | 58 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 60 | 75 | 75 | 65 | 60 | 62 | 69 | 63 | 69 | 70 | 62 | 68 | 64 | 66 | 69 | 67 | 73 | |

| N/A | 63 | 60 | 64 | 64 | 66 | 61 | 67 | 65 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 66 | 67 | 71 | 61 | 54 | 47 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 49 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 57 | 53 | 53 | 67 | |||||||

| 1999 | 72 | 73 | 78 | 80 | 76 | 79 | 83 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 85 | 87 | 88 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 86 | 86 | 84 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 67 | 69 | 70 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 76 | 80 | 85 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 90 | |

| 1999 | 83 | 79 | 87 | 76 | 82 | 70 | 69 | 62 | 67 | 64 | 66 | 64 | 67 | 63 | 58 | 61 | 61 | 63 | 64 | 68 | 67 | 57 | 53 | 57 | 59 | 53 | 54 | 54 | 59 | 55 | 54 | 53 | 58 | 59 | 61 | 63 | 70 | |

| 2014 | 55 | 59 | 57 | 55 | 46 | 53 | 47 | 48 | 54 | 47 | 48 | 53 | 55 | 52 | 53 | 42 | 39 | 35 | 43 | 53 | 68 | 74 | 78 | 72 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 83 | 81 | 83 | |||||||

| 2015 | 63 | 69 | 60 | 54 | 46 | 55 | 54 | 48 | 57 | 48 | 52 | 52 | 50 | 51 | 48 | 46 | 42 | 43 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 63 | 73 | 67 | 65 | 67 | 65 | 68 | 65 | 67 | 83 | |||||||

| 1999 | 81 | 84 | 91 | 89 | 88 | 83 | 88 | 85 | 87 | 89 | 81 | 84 | 81 | 85 | 82 | 83 | 86 | 80 | 79 | 86 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 72 | 77 | 79 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 82 | 87 | 85 | 77 | 81 | 85 | 83 | |

| 2008 | 46 | 46 | 50 | 50 | 47 | 55 | 64 | 63 | 72 | 63 | 68 | 66 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 61 | 63 | 64 | 68 | 69 | 73 | 77 | 78 | 74 | 75 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 72 | 74 | 80 | |||||||

| 1999 | 66 | 71 | 75 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 58 | 72 | 71 | 71 | 70 | 73 | 77 | 81 | 80 | 83 | 81 | 81 | 71 | 76 | 74 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 68 | 71 | 76 | 76 | 75 | 75 | 77 | 77 | 79 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 84 | |

| N/A | 59 | 65 | 56 | 50 | 54 | 52 | 54 | 49 | 49 | 44 | 47 | 46 | 43 | 47 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 36 | 29 | 35 | 37 | 40 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 34 | 32 | 36 | 34 | 36 | 35 | |||||||

| 1999 | 59 | 67 | 73 | 70 | 75 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 65 | 67 | 57 | 63 | 64 | 60 | 54 | 53 | 54 | 61 | 53 | 56 | 49 | 54 | 58 | 55 | 52 | 50 | 59 | 58 | 62 | 67 | 69 | 74 | 74 | 77 | 80 | 77 | 85 | |

| N/A | 74 | 71 | 74 | 66 | 65 | 70 | 73 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 64 | 64 | 65 | 61 | 60 | 56 | 56 | 58 | 63 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 57 | 55 | 60 | 57 | 61 | 55 | 83 | |||||||

| 2009 | 68 | 69 | 72 | 60 | 63 | 65 | 69 | 63 | 66 | 76 | 89 | 86 | 87 | 89 | 82 | 78 | 80 | 72 | 77 | 78 | 74 | 79 | 81 | 78 | 78 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 77 | 77 | 81 | |||||||

| 2007 | 85 | 87 | 83 | 77 | 82 | 83 | 91 | 86 | 90 | 90 | 86 | 88 | 82 | 83 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 83 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 75 | 78 | 77 | 80 | 85 | 83 | 85 | 84 | 86 | 91 | |||||||

| 1999 | 68 | 69 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 70 | 74 | 69 | 58 | 61 | 60 | 64 | 68 | 68 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 62 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 63 | 55 | 63 | 52 | 56 | 60 | 65 | 61 | 67 | 68 | 71 | 75 | 82 | 76 | 78 | 86 | |

| N/A | 29 | 51 | 49 | 51 | 41 | 41 | 45 | 46 | 48 | 44 | 50 | 51 | 45 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 51 | 52 | 34 | 37 | 34 | 23 | 27 | 23 | 19 | 23 | 19 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 23 | |

| N/A | 59 | 61 | 67 | 63 | 66 | 59 | 60 | 63 | 59 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 63 | 61 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 60 | 56 | 58 | 56 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 51 | 52 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 56 | 55 | 58 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 62 | 70 | |

| Eurozone | 79 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| N/A | 25 | 27 | 31 | 28 | 24 | 23 | 26 | 31 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 29 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 19 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 17 | 24 | 23 | 30 | 27 | 28 |

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |