Melvin Edwards facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Melvin Edwards

|

|

|---|---|

Edwards in 2024

|

|

| Born |

Melvin Eugene Edwards, Jr.

May 4, 1937 |

| Alma mater | University of Southern California (BFA) |

| Known for | Sculpture |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Karen Hamre

(m. 1960, divorced) |

Melvin "Mel" Edwards (born May 4, 1937) is an American artist known for his abstract sculptures. He also creates prints and teaches art. Edwards, an African-American artist, grew up in both segregated (separated by race) and integrated (mixed race) communities in the United States.

He started his art career in California in the 1950s. Edwards first studied painting but soon began working with sculpture and welding in the early 1960s. He moved to New York in 1967.

Edwards is famous for his Lynch Fragments sculptures. These are small, abstract steel artworks made from welded metal objects like spikes, scissors, and chains. He started this series in 1963. Edwards said these works are like metaphors for the challenges and triumphs of African Americans in the United States.

He also created large sculptural environments using barbed wire and chains. His Rockers sculptures are painted metal pieces that can rock back and forth. Edwards also makes huge outdoor sculptures, often using geometric metal shapes and large chain designs. He has also made many prints throughout his career. Even though his art is abstract, it often connects to African-American and African history, as well as current events.

Edwards has had many solo art shows in museums and galleries worldwide. In 1970, he was the first African-American sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York. His art gained more attention in the 2000s and 2010s. Edwards also taught art at several universities, including Rutgers University for 30 years. He lives and works in upstate New York, New Jersey, and Senegal.

A special exhibition of Edwards's work is currently on display at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland. It will be there until August 17, 2025.

Contents

- Early Life and Art Education

- Life and Art Career

- Early Sculptures and Lynch Fragments

- Growing Recognition and New York

- Community Art and Barbed Wire

- 1970s: Whitney Show and Rockers

- 1980s: Public Art and Travel

- 1990s: First Commercial Show and Retrospective

- 2000s: Senegal and Retirement

- 2010s: Major Retrospectives and Venice Biennale

- 2020s: Public Art and European Shows

- Public Artworks

- Exhibitions

- Awards and Honors

- Notable Artworks in Public Collections

- See Also

Early Life and Art Education

Melvin Eugene Edwards Jr. was born on May 4, 1937, in Houston, Texas. He was the oldest of four children. His family moved to McNair, Texas, in 1942, and then to Dayton, Ohio, in 1944. In Dayton, Edwards went to schools that were racially integrated, meaning students of all races attended together.

He first understood art in fourth grade when his teacher taught figure drawing. Edwards noticed his drawing was more realistic than his classmates'. He often visited the Dayton Art Institute with his family and school.

In 1949, his family moved back to Houston, Texas. Edwards grew up in Houston during a time of racial segregation, where black and white people were kept separate. He started making art seriously at a young age. His father, who was an amateur painter, encouraged him. A high school teacher introduced Edwards to abstract art. He also took art classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Edwards was also a keen athlete and played football in high school.

After high school, he moved to Los Angeles in 1955. He worked part-time to pay for classes at Los Angeles City College. He later transferred to the University of Southern California (USC) to play football and study art. At USC, he focused on painting. He also studied sculpture at the Los Angeles County Art Institute. Edwards returned to USC on a football scholarship. He learned about African history later in life, partly because he felt his college history classes were too focused on Europe.

While at USC, Edwards met Karen Hamre, an art student. They married in 1960 and had their first daughter that year. Edwards became friends with other artists in Los Angeles. He also met Charles White, a famous African-American artist. Edwards spent time at Dwan Gallery, where he met artists known for minimalism and land art. He finished most of his college work by 1960 but received his degree in 1965.

Life and Art Career

Early Sculptures and Lynch Fragments

After college, Edwards learned to weld from a graduate student named George Baker. He took more classes in 1962 to improve his welding skills. To support his family, Edwards worked at a ceramics factory and a film production company. He also visited the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, where he met famous artists and curators. He was inspired by Mexican muralist artists like David Alfons Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. He wanted to use his art to share his social and political views.

In the early 1960s, Edwards experimented with welding. In 1963, he created a small abstract sculpture called Some Bright Morning. It was made of steel, a blade, and a chain. The title came from a story about a black family in Florida who fought back against threats. This sculpture was the first in his Lynch Fragments series. These small, welded metal wall sculptures were inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. Edwards described them as representing the struggles of African Americans. He used various metal objects like hammer heads, scissors, and chains in these works.

Edwards visited New York for the first time in 1963. He met artists like William Majors and Hale Woodruff. He showed Woodruff some of his Lynch Fragments. In the mid-1960s, Edwards helped Dwan Gallery repair sculptures by other artists.

Growing Recognition and New York

Edwards had his first solo art show in 1965 at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. He showed Lynch Fragments and a new work called Chaino. Chaino was a metal sculpture suspended in the air by chains. A critic praised his skill and understanding of materials. In 1965, Edwards also started teaching at the Chouinard Art Institute. His twin daughters were born that same year.

Around this time, he began making new works with abstract metal forms suspended inside metal frames. One such work from 1965 was The Lifted X, named in honor of Malcolm X after his death. This piece has a large metal form with a meat hook hanging from it, above an "X" shape. In 1966, Edwards created Cotton Hangup, another suspended sculpture. He said these works explored the idea of "suspension."

His art was part of a big exhibition called The Negro in American Art at UCLA in 1966. He became friends with artist Sam Gilliam after seeing his work there. Edwards moved to New York in January 1967 with his family. Other artists encouraged him to move there for more opportunities. Soon after, Edwards and his wife separated, and she returned to California with their daughters. Edwards began teaching art at Orange County Community College.

He met artists William T. Williams and Frank Bowling, who became close friends and supporters of his work. In 1968, Edwards created large abstract geometric sculptures made of painted metal during a residency in Minneapolis. These sculptures used bright, primary colors. The Walker Art Center showed these works.

Community Art and Barbed Wire

Edwards joined Smokehouse (also known as Smokehouse Associates) in New York. This was a community project led by William T. Williams. They created large wall paintings with geometric patterns in Harlem, working with local community members. This project aimed to create public art that helped communities. Edwards saw this work as connected to the Mexican muralists he admired. He participated in Smokehouse during the summers of 1968 and 1969.

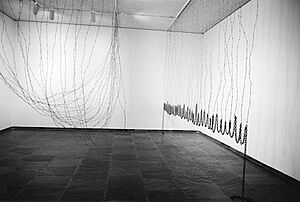

In late 1968, Edwards began a new series of barbed-wire sculptures. These works used strands of barbed wire and chain stretched across gallery spaces, creating environments rather than single sculptures. In 1969, Edwards created drawings for a poetry book by Jayne Cortez. They had met before but became closer while working on her first book, ... Stairs and the Monkey Man's Wares.

Edwards, Williams, and Gilliam showed their art together in June 1969 at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Edwards displayed his first barbed-wire installations, including Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid. This piece was a pyramid shape made of barbed wire in a corner of the gallery. These artists, all African-American and making abstract art, had more shows together in the 1970s. At the time, some black artists felt art should have a clear political purpose, but Edwards's abstract works explored different ideas.

In fall 1969, Frank Bowling organized an exhibition called 5+1 at SUNY Stony Brook. It featured six black abstract artists, including Edwards. Edwards showed Curtain for William and Peter, a wall of barbed wire strands that divided the gallery space.

Edwards also completed his first major public sculpture in 1969. It was called Homage to My Father and the Spirit and was made for Cornell University. The sculpture is a large stainless-steel disc connected to a triangular steel panel painted in bright colors. That same year, he met the French poet Léon-Gontran Damas, a founder of the Négritude movement. Damas became a friend and mentor to Edwards.

1970s: Whitney Show and Rockers

In early 1970, Edwards was invited to an exhibition called Afro-American Artists but chose not to participate. He felt that white artists were not asked if they objected to being in "white shows."

In March 1970, Edwards had a solo exhibition, Melvin Edwards: Works, at the Whitney Museum in New York. He was the first African-American sculptor to have a solo show there. Edwards chose to display his barbed-wire installations, including new works like Corner for Ana and "look through minds mirror distance and measure time" – Jayne Cortez. He also recreated Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid and Curtain for William and Peter. The exhibition influenced artist David Hammons.

In 1970, Edwards started his Rockers series. These are kinetic sculptures built on large metal half-circles that can rock. Edwards was inspired by his grandmother Coco's rocking chair. He connected the rocking movement to syncopation in African-American music, especially jazz. The first work, Homage to Coco (1970), had two painted steel half-circles with chains that swung as it rocked. It was shown at the Whitney Museum's annual sculpture exhibition. That same year, he installed his second public sculpture, Double Circles, in Harlem. This sculpture had large vertical steel circles that people could walk through.

Edwards became an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut in 1970. That summer, he took his first trip to Africa, visiting Nigeria, Togo, Benin, and Ghana. He traveled with a program called "Educators to Africa" with Jayne Cortez and other African-American teachers. He has traveled to Africa many times since, saying it greatly influenced his work. In Benin City, Nigeria, he learned bronze casting from Chief Moregbe Inneh.

In 1971, Edwards withdrew his work from a Whitney Museum exhibition called Contemporary Black Artists in America. He and 24 other black artists protested because the museum would not hire a black curator for the show. Edwards published a statement in Artforum criticizing the museum's treatment of black artists. He also returned to Nigeria in 1971.

In 1972, he became an assistant professor at Rutgers University. That same year, Edwards, Gilliam, and Williams had a three-person exhibition called Interconnections in Chicago. One work was Good Friends in Chicago, a Rockers sculpture with two stacked metal forms. Edwards said he made it in Chicago because there was no money to ship his art.

Edwards had stopped making prints after college, but in 1973, printmaker Robert Blackburn encouraged him to start again. He made several prints at Blackburn's workshop. He also traveled to Nigeria again. In 1973, Edwards briefly returned to making new Lynch Fragments sculptures due to racial tensions in New York. He showed them in several exhibitions, including Extensions in 1974. Edwards and Cortez married in 1975.

In 1976, Edwards had another exhibition with Gilliam and Williams called Resonance. He showed works named after his travels to Africa, like Angola 1973. Edwards participated in FESTAC (the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1977. He met many artists from the African diaspora there, which he found very important.

The Studio Museum in Harlem held Edwards's first retrospective exhibition in 1978. It included Lynch Fragments, Rockers, and a steel work dedicated to his friend Léon-Gontran Damas, who died that year. The exhibition did not receive much attention from critics. Seeing his Lynch Fragments together inspired him to start making new works in that series again. In 1978, he also became the American editor for a Nigerian art journal, writing about African-American art.

1980s: Public Art and Travel

In 1980, Edwards became a full professor at Rutgers. That year, he traveled to Egypt, Kenya, Gambia, and France. In 1981, he went to Cuba with Jayne Cortez and other artists. He gave a lecture about African-American art and met Cuban artists like Wifredo Lam. Edwards later made a sculpture in Lam's memory.

In 1982, Edwards created a sculpture for a public housing complex in Columbus, Ohio. The work, Out of the Struggles of the Past to a Brilliant Future, used steel half-discs and geometric shapes to form an archway. It also featured a large, column-like section of oversized steel chain. This was the first time he used the chain motif in his large, freestanding sculptures. He received several more commissions for public artworks in the 1980s, including in North Carolina and New Jersey. In 1984, he had a major exhibition of his sculptures in Paris. He showed many new Lynch Fragments, including At Cross Roads, which included a metal vise.

Edwards traveled widely in the 1980s, visiting Nicaragua, France, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Gabon, and Brazil. In 1988, he made a Lynch Fragment called Palmares to mark 100 years since slavery was abolished in Brazil. He received a Fulbright Fellowship to Zimbabwe in 1988. While there, he taught metalworking workshops and created new Lynch Fragments, which were the largest in the series so far.

Even though he continued to create new art, his career in New York faced some challenges in the 1980s. Some critics felt his abstract art was not as politically valuable as figurative art. Also, the serious subject of his Lynch Fragments was difficult for some in the art world. In 1988, a critic called Edwards "one of the best American sculptors" but also "one of the least known."

In 1989, Edwards completed a large outdoor sculpture called Confirmation for the Social Security Administration building in Queens, New York. It was made of large stainless-steel geometric shapes, including a disc, a triangle, and an arch.

1990s: First Commercial Show and Retrospective

Edwards continued making Lynch Fragments throughout the 1980s. He showed many of them in a ten-year exhibition at Montclair State College in 1990. He also had his first solo commercial gallery exhibition in New York in 1990. He showed seventeen Lynch Fragments and a large freestanding steel work called To Listen. Museums like the Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Modern Art bought sculptures from this show. The gallery owner noted it was harder to sell Lynch Fragments to private collectors. Edwards said he just kept working even when his career didn't take off as he expected after his Whitney Museum show.

In 1993, Edwards had a 30-year retrospective exhibition at the Neuberger Museum of Art in New York. A critic from The New York Times wrote that his art didn't fit neatly into common art styles, which might explain why it took so long for a museum to give him such a serious show. That same year, Edwards won the grand prize at the Fujisankei Biennale Sculpture Competition in Japan for his outdoor sculpture Asafo Kra No. This large painted-steel work had a chain and a rocking element. It was permanently installed at a museum in Nagano.

In 1996, Edwards traveled to Senegal for an artist residency. He created a print portfolio there with other artists.

2000s: Senegal and Retirement

With help from an artist friend, Edwards and Cortez began living part-time in Dakar, Senegal, in 2000. Edwards set up a studio there. In Senegal, he started making new Lynch Fragments-style works. These included local metal drainage covers onto which he mounted his sculptures. Around the same time, he and Cortez bought a larger property in upstate New York. Also in 2000, Edwards had an exhibition of his prints, drawings, and small sculptures at the Jersey City Museum.

Edwards retired from teaching at Rutgers University in 2002. He moved most of his large sculptures to storage in New York but kept his New Jersey studio active. He now has art studios in Accord, New York, Plainfield, New Jersey, and Dakar. In 2006, his work was part of an exhibition called Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction, 1964–1980 at the Studio Museum in Harlem. This show helped to re-examine the work of black abstract artists like Edwards.

In 2008, he completed Transcendence, a large sculpture for Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. This work, made of stainless-steel geometric shapes and chain links, honors David K. McDonogh. McDonogh was a 19th-century ophthalmologist who escaped slavery and went to Lafayette College.

2010s: Major Retrospectives and Venice Biennale

In fall 2010, Edwards had an exhibition of new and old works in New York. He showed newer Lynch Fragments that referenced current events like the Iraq War. Critics praised the exhibition, noting the "quiet, undiminished integrity" of his art. Several of his Lynch Fragments were shown in Los Angeles in 2011. This led to new interest in his work from younger curators. In 2012, he recreated his barbed-wire sculpture Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid at the Art Basel art fair. Jayne Cortez passed away in 2012.

In 2014, Edwards had his first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom in London. It featured sculptures, drawings, and a special installation. A critic noted that renewed interest in Edwards's work was important, given the similarities between the struggles of the 1960s and current events.

The Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas opened a 50-year retrospective of Edwards's work in January 2015. It included art from every period of his career. One part of the exhibition recreated his barbed-wire sculptures from his 1970 Whitney Museum show. Edwards's work was also included in the 56th Venice Biennale in May 2015. This was the first time an African curator organized the exhibition. Edwards's Lynch Fragments were displayed in two rows, making visitors walk between them. His inclusion in the Biennale brought even more attention to his career.

Edwards traveled to Oklahoma in 2016 for an artist residency. He used materials from local scrapyards to create new works, including sculptures with metal forms suspended by chains. He showed these new pieces in his 2017 exhibition In Oklahoma. Also in 2017, Edwards had a solo exhibition at Brown University. Among the new works was Corner for Ana (Scales of Injustice), an installation with a scale holding metal pieces behind barbed wire. Edwards said it was inspired by a migrant who drowned in Venice while people filmed instead of helping. That same year, several of his sculptures were in the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at the Tate Modern in London. This important show featured Curtain for William and Peter and Some Bright Morning.

In 2018, the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) hosted a large exhibition of Edwards's Lynch Fragments. The following year, Edwards returned to Brazil for a residency. He created many new works, including the room-sized installation Continuous Resistance Room and six new Lynch Fragments. These works were shown in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Bahia. Also in 2019, Edwards had a solo exhibition called Crossroads at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Throughout the 2010s, many museums bought Edwards's work as interest in his career grew. He also began experimenting with creating tapestries.

2020s: Public Art and European Shows

In 2021, the Public Art Fund organized Melvin Edwards: Brighter Days. This exhibition of Edwards's outdoor sculptures from 1970 to 2020 was held in New York's City Hall Park. It included Homage to Coco (1970) and a new large sculpture called Song of the Broken Chains. The exhibition was originally planned for 2020 but was postponed by Edwards to support the Black Lives Matter protests.

In April 2022, Edwards, Gilliam, and Williams had their final three-artist exhibition together. Gilliam passed away in June of that year. Also in 2022, the Dia Art Foundation opened a long-term installation of Edwards's barbed-wire sculptures at Dia Beacon. These sculptures had only existed as sketches before.

In 2023, Edwards had a solo exhibition in Berlin, Germany. He showed sculptures, drawings, and an installation called Now’s the Time. This piece featured a saxophone hanging from the ceiling behind barbed wire. Also in 2023, Edwards completed the public sculpture David's Dream. It was commissioned in honor of art historian David Driskell. The sculpture, made of stainless-steel discs, geometric shapes, and large chains, was installed at the University of Maryland, College Park in 2024.

Edwards had his first solo museum exhibition in Europe in 2024 at the Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany. This exhibition, Some Bright Morning, included Lynch Fragments, large metal sculptures, and drawings and prints. A version of this exhibition opened at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland on June 12, 2025, and is currently on view.

Public Artworks

Edwards has created many large public sculptures. Some of his notable public artworks include:

- Homage to My Father and the Spirit (1969) at Cornell University

- Homage to Billie Holiday and the Young Ones of Soweto (1976–1977) at Morgan State University

- Out of the Struggles of the Past to a Brilliant Future (1982) in Columbus, Ohio

- Breaking of the Chains (1995) in San Diego

- David's Dream (2023) at the University of Maryland, College Park

Exhibitions

Edwards has had many solo shows in the United States and other countries. Some important solo exhibitions include:

- Melvin Edwards (1965) at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, his first solo museum show.

- Melvin Edwards: Works (1970) at the Whitney Museum, his first solo museum show in New York and the first by an African-American sculptor there.

- Melvin Edwards (1990) at CDS Gallery in New York, his first solo show at a commercial gallery.

- Melvin Edwards (2014–2015) at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, his first solo exhibition in the UK.

- Melvin Edwards (2022), a long-term installation of previously unbuilt sculptures at Dia Beacon.

He has also had several museum retrospective exhibitions, which look back at his entire career:

- Melvin Edwards: Sculptor (1978) at the Studio Museum in Harlem, his first retrospective.

- A 30-year traveling retrospective in 1993, starting at the Neuberger Museum of Art in New York.

- A 50-year traveling retrospective in 2015, starting at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.

- Some Bright Morning (2024–2025), his first traveling retrospective in Europe, starting at the Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany.

Edwards has also participated in many group exhibitions, including the 56th Venice Biennale (2015) and the Havana Biennial (2019).

Awards and Honors

Edwards has received many grants and fellowships:

- National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) fellowships in 1971 and 1984.

- A Guggenheim Fellowship in 1975.

- A Fulbright Fellowship to Zimbabwe in 1988.

He was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate in 1992 and became a full Academician in 1994. He has also received honorary degrees from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Brooklyn College.

Edwards received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center in 2024.

Notable Artworks in Public Collections

- Chaino (1964), Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts

- August the Squared Fire (1965), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- The Lifted X (1965), Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Curtain for William and Peter (1969/1970), Tate, London

- Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid (1969/1970), Whitney Museum, New York

- Gate of Ogun (1983), Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York

- Justice for Tropic-Ana (dedicated to Ana Mendieta) (1986), from the series Lynch Fragments, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

- Good Word from Cayenne (1990), from the series Lynch Fragments, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Off and Gone (1992), from the series Lynch Fragments, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

- Tambo (1993), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Siempre Gilberto de la Nuez (1994), from the series Lynch Fragments, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Soba (2002), from the series Lynch Fragments, Detroit Institute of Arts

- Scales of Injustice (2017/year of exhibition), Baltimore Museum of Art

See Also

- Abstract art by African-American artists

- List of African-American visual artists