Peter Heywood facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Heywood

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by John Simpson

|

|

| Born | 6 June 1772 Douglas, Isle of Man |

| Died | 10 February 1831 (aged 58) London |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1786–1816 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held | HMS Amboyna HMS Vulcan HMS Trincomalee HMS Trident HMS Leopard HMS Dedaigneuse HMS Polyphemus HMS Donegal HMS Nereus HMS Montagu |

| Battles/wars | |

| Alma mater | St Bees School |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Joliffe |

| Children | One daughter |

| Relations | Sir Thomas Pasley (uncle) |

Captain Peter Heywood (born June 6, 1772 – died February 10, 1831) was a British Royal Navy officer. He was on board HMS Bounty during the famous mutiny on April 28, 1789. Later, he was found in Tahiti, put on trial, and sentenced to death. However, he was then pardoned. He went back to his naval career and retired as a post-captain after 29 years of service.

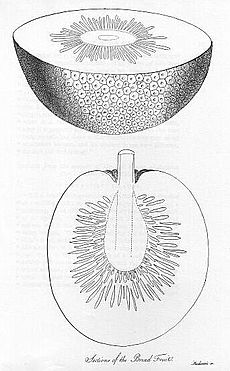

Peter Heywood came from an important family on the Isle of Man with many naval connections. He joined the Bounty at age 15. Even though he wasn't officially ranked, he had the benefits of a junior officer. The Bounty left England in 1787. Its mission was to collect breadfruit from the Pacific. It arrived in Tahiti in late 1788. The ship's captain, William Bligh, had problems with some of his officers, especially Fletcher Christian. These problems got worse during the five months the Bounty stayed in Tahiti.

Soon after the ship started its journey home, Christian and his unhappy followers took control of the ship. Bligh and 18 loyal crew members were put into a small open boat and left at sea. Heywood was one of those who stayed on the Bounty. Later, he and 15 others left the ship and settled in Tahiti. The Bounty then sailed on to Pitcairn Island. Bligh, after an amazing journey in the open boat, eventually reached England. There, he said Heywood was one of the main people who started the mutiny. In 1791, Heywood and his friends in Tahiti were found by the search ship HMS Pandora. They were arrested and held in chains to be taken back to England. Heywood and another sailor were happy to see the Pandora, thinking they were rescued. But they were arrested. The captain, Edward Edwards, put them and 12 others in an 11-foot box on deck. During their journey, the Pandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef. Four of Heywood's fellow prisoners drowned.

In September 1792, Heywood faced a court martial. He and five others were sentenced to be hanged. But the court suggested that Heywood should be shown mercy. King George III then pardoned him. His luck quickly changed. Senior officers started to favor him. After he returned to his career, he received many promotions. He got his first command at age 27 and became a post-captain at 31. He stayed in the navy until 1816. He had a good career as a hydrographer, which means he made maps of the sea. After that, he had a long and peaceful retirement.

It's not fully clear how guilty Heywood really was in the mutiny. There were different stories and possibly false statements during his trial. His powerful family connections helped him a lot. He also benefited from efforts by Christian's family to make Bligh look bad. They tried to show the mutiny as a fair reaction to Bligh's harsh rule. Newspapers at the time and later writers have compared Heywood's pardon to the fate of other prisoners who were hanged. These were common sailors who didn't have money or family influence and couldn't afford lawyers.

Contents

Peter Heywood's Early Life

Peter Heywood was born in 1772 at the Nunnery in Douglas, Isle of Man. He was the fifth of 11 children. His parents were Peter John Heywood and Elizabeth Spedding. The Heywood family had a long history, going back to the 12th century. One famous ancestor was Peter "Powderplot" Heywood. He arrested Guy Fawkes after the 1605 plot to blow up the English parliament. On his mother's side, Peter was related to Fletcher Christian's family. Christian's family had lived on the Isle of Man for many centuries.

In 1773, when Peter was one year old, his father had to sell The Nunnery. The family moved to Whitehaven, England, for several years. Later, his father got a job as an agent for the Duke of Atholl's properties on the Isle of Man. This brought the family back to Douglas.

Heywood's family had a tradition of serving in the navy and military. In 1786, at age 14, Heywood left St Bees School in England. He joined HMS Powerful, a training ship in Plymouth. In August 1787, Heywood was offered a spot on the Bounty. This was for a long trip to the Pacific Ocean under Lieutenant William Bligh. A family friend, Richard Betham, who was also Bligh's father-in-law, recommended Heywood. The Heywood family was having money problems at this time. Peter John Heywood had lost his job with the Duke. Betham wrote to Bligh, asking him to help the family. Bligh was happy to help. He invited young Heywood to stay with him in Deptford while the ship was getting ready.

On the HMS Bounty

The Journey Out

The Bounty's job was to collect breadfruit plants from Tahiti. These plants were to be taken to the West Indies. They would be a new food source for plantations there. Bligh was a skilled navigator. He had been to Tahiti in 1776 as Captain James Cook's sailing master. The Bounty was a small ship, about 91 feet long. It had 46 men crowded into small living spaces. Heywood was one of several "young gentlemen" on board. They were listed as able seamen but ate and slept with officers in the cockpit. His distant relative, Fletcher Christian, was a master's mate on the trip.

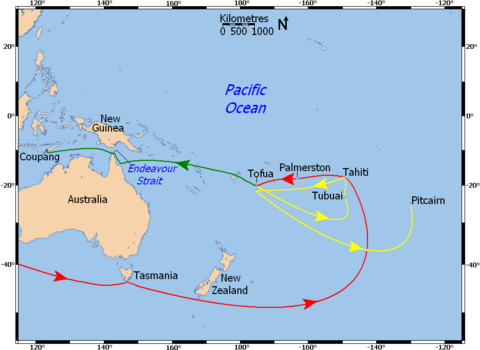

Bligh's orders were to enter the Pacific by sailing around Cape Horn. After collecting enough breadfruit plants from Tahiti, he was to sail west. He would go through the Endeavour Strait and across the Indian Ocean. Then, entering the Atlantic, he would continue to the West Indies. This would complete a circumnavigation of the world.

The Bounty left London on October 15, 1787. It was held at Spithead waiting for final orders. Bad weather caused more delays. It was December 23 before the ship finally sailed. This long wait meant the Bounty arrived at Cape Horn much later than planned. They met very severe weather. Bligh could not make progress against strong westerly winds and huge waves. He finally turned the ship and headed east. This meant taking a longer route to the Pacific. They would sail first to Cape Town, then south of Australia and New Zealand, before heading north to Tahiti.

Following its new route, the Bounty reached Cape Town on May 24, 1788. Here, Heywood wrote a long letter to his family. He described the journey so far. He gave vivid details of life at sea. Heywood said sailing had been "in the most pleasurable weather imaginable" at first. When describing the attempts to go around Cape Horn, he wrote: "I suppose there never were seas... to compare with those we met... for height, and length of swell." He said the oldest sailors on board had never seen anything like it. Heywood recorded that Bligh's decision to turn east was "to the great joy of everyone on board."

Time in Tahiti

The Bounty sailed from Cape Town on July 1, 1788. It reached Tasmania on August 19. Then it arrived at Matavai Bay, Tahiti, on October 26. However, during the last parts of this journey, problems started between Bligh and his officers and crew. Arguments and disagreements became more frequent.

When they arrived, Heywood and Christian were sent to a camp on shore. This camp would be a nursery for the breadfruit plants. They lived there for the whole time in Tahiti. This was a "comfortable and privileged situation." Historian Richard Hough said it was envied by those who had to stay on the ship. Whether crew members were ashore or on board, duties during the Bounty's five-month stay in Tahiti were quite easy.

Despite the relaxed atmosphere, relations between Bligh and his men continued to get worse. This was especially true between Bligh and Christian. Christian was often shamed by the captain. This happened in front of the crew and the native Tahitians. It was for real or imagined laziness. Also, severe punishments were given to men whose carelessness led to lost or stolen equipment. Floggings, which were rare on the way out, became common. As a result, three men ran away from the ship. They were quickly caught. A search of their things showed a list of names, including Christian and Heywood. Bligh confronted them and accused them of helping the deserters. They strongly denied it. Without more proof, Bligh could not act against them.

As the departure date from Tahiti got closer, Bligh's outbursts against his officers became more frequent. One witness said that "Whatever fault was found, Mr Christian was sure to bear the brunt." Tensions grew among the men. They faced a long and dangerous journey through the unknown Endeavour Strait. This would be followed by many months of hard sailing. Bligh was eager to leave. But, as Hough said, he "failed to anticipate how his company would react to the severity and austerity of life at sea... after five dissolute, hedonistic months at Tahiti." On April 5, 1789, the Bounty finally left and sailed into the open sea.

The Mutiny

Taking Control of the Bounty

For three weeks, the Bounty sailed west. Early on April 28, 1789, it was near Tofua island in the Friendly Islands (Tonga). Christian was the officer on watch. Bligh's behavior towards him had become very harsh. Christian was now ready to take over the ship. He had help from a group of armed sailors who would follow him.

Shortly after 5:15 AM local time, Bligh was seized and brought on deck. He was wearing only his nightshirt, and his hands were tied. There were hours of confusion as most of the crew tried to understand what was happening and decide what to do. Finally, around 10 AM, Bligh and 18 loyal crew members were put into the ship's launch. This was a 23-foot open boat with very few supplies and navigation tools. They were left at sea. Heywood was among those who stayed on board.

Not all 25 men who stayed on the Bounty were mutineers. Bligh's launch was too full. Some who stayed did so because they were forced. Bligh reportedly said, "Never fear, lads, I'll do you justice if ever I reach England." However, Bligh was sure that Heywood, who was not yet 17, was as guilty as Christian. In a letter to his wife, Betsy, Bligh called Heywood "one of the ringleaders." He added: "I have now reason to curse the day I ever knew a Christian or a Heywood." Bligh's later official report to the Admiralty listed Heywood with Christian and others as leaders of the mutiny. He described Heywood as a young man with talent for whom he had cared a lot. To the Heywood family, Bligh wrote: "His baseness is beyond all description."

Crew members later gave different stories about Heywood's actions during the mutiny. Boatswain William Cole said Heywood was kept on the ship against his will. Ship's carpenter William Purcell thought Heywood's unclear behavior was due to his youth and the excitement. He believed Heywood had no part in the uprising itself. On the other hand, Midshipman John Hallett reported that Bligh, with a bayonet at his chest and his hands tied, spoke to Heywood. Hallett claimed Heywood "laughed, turned round and walked away." Another midshipman, Thomas Hayward, said he asked Heywood his plans. Heywood told him he would stay with the ship. Hayward thought this meant Heywood had joined the mutineers.

After Bligh's boat left, Christian turned the Bounty east. He was looking for a hidden place where he and the mutineers could settle. He thought of Tubuai island, 300 nautical miles south of Tahiti. Christian planned to pick up women, servants, and animals from Tahiti. This would help start the new settlement. As the Bounty slowly sailed towards Tubuai, Bligh's boat faced many dangers. But it steadily made its way towards civilization. It reached Coupang (now Kupang), on Timor, on June 14, 1789. Here, Bligh gave his first report of the mutiny. He waited for a ship to take him back to England.

Living as a Fugitive

A month of sailing brought the Bounty to Tubuai on May 28, 1789. The island's natives were not friendly. But Christian spent several days looking at the land. He chose a spot for a fort. Then he took the Bounty to Tahiti. When they reached Matavai Bay, Christian made up a story. He said that he, Bligh, and Captain Cook were starting a new settlement at Aitutaki. Cook's name helped them get many gifts of animals and other goods. On June 16, the well-supplied Bounty sailed back to Tubuai. It had nearly 30 Tahitians, some of whom had been tricked into coming aboard. The attempt to start a colony on Tubuai failed. The mutineers often raided for "wives." The tricked Tahitians were also very unhappy. This ruined Christian's plans.

On September 18, 1789, the Bounty sailed back to Matavai Bay for the last time. Heywood and 15 others decided to stay in Tahiti. They would risk being discovered. Christian, with eight mutineers and many Tahitian men and women, took off in the Bounty for a secret place. Before leaving, Christian left messages for his family with Heywood. He told the story of the mutiny and said he alone was responsible.

In Tahiti, Heywood and his friends started to organize their lives. The largest group, led by James Morrison, began building a schooner. They named it Resolution after Cook's ship. Matthew Thompson and former master-at-arms Charles Churchill chose to live wild and drunken lives. Both ended up dying violently. Heywood preferred a quiet life in a small house with a Tahitian wife. He studied the Tahitian language and had a daughter. Over 18 months (from September 1789 to March 1791), he slowly started to dress like the natives. He also got many tattoos on his body. Heywood later explained: "I was tattooed not to gratify my own desires, but theirs." He added that in Tahiti, a man without tattoos was an outcast. He said, "I always made it a rule when I was in Rome to act as Rome did."

This peaceful life ended on March 23, 1791. The search ship HMS Pandora arrived. Heywood later wrote that his first feeling was "the utmost joy." As the ship anchored, he went out in a canoe to identify himself. However, he and others who came aboard willingly were not welcomed. Captain Edward Edwards, Pandora's commander, treated all the former Bounty men the same. All were made prisoners, manacled, and taken below deck.

Peter Heywood as a Prisoner

The Pandora Voyage

Within a few days, all 14 surviving fugitives in Tahiti had either given up or been caught. Among Pandora's officers was former Bounty midshipman Thomas Hayward. Heywood hoped his old shipmate would confirm his innocence. But his hopes were quickly crushed. Hayward "received us very coolly, and pretended ignorance of our affairs."

The Pandora stayed in Tahiti for five weeks. Captain Edwards tried to find out where the Bounty was, but he failed. A cell was built on Pandora's quarterdeck. This structure was called "Pandora's Box." The prisoners, with their legs in irons and wrists in handcuffs, were kept there for almost five months. Heywood wrote: "The heat... was so intense that the sweat frequently ran in streams... and the two necessary tubs... helped to render our situation truly disagreeable."

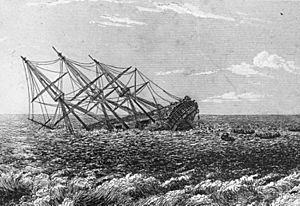

The Pandora left Tahiti on May 8, 1791. It searched for Christian and the Bounty among the thousands of southern Pacific islands. They found a few pieces of wood at Palmerston Island (Avarau), but no other signs of the ship. Attacks from natives were common. In early August, Edwards stopped the search. He headed for the Dutch East Indies through the Torres Strait. They knew very little about these waters and the reefs. On August 29, 1791, the ship hit the outer Great Barrier Reef and started to fill with water.

Three prisoners in "Pandora's Box" were let out. They were told to help the crew pump water. As the crew tried to save the ship, the other men in "Pandora's Box" were forgotten. At dawn, it was clear the ship could not be saved. The officers agreed to abandon ship. The armor-maker was ordered into the "box" to remove the remaining prisoners' leg irons and shackles. However, the ship sank before he finished. Heywood was one of the last to get out of the cell. Four prisoners, including Heywood's best friend George Stewart, drowned. Thirty-one regular crew members also drowned.

The 99 survivors, including ten prisoners, recovered on a nearby island. They stayed there for two nights. Then they started an open-boat journey. This journey was much like Bligh's trip two years earlier. The prisoners were mostly kept tied up on the slow trip to Coupang. They reached Coupang on September 17, 1791.

During this long ordeal, Heywood managed to keep his prayer book. He used it to write down dates, places, and events during his captivity. He recorded that at Coupang, he and his fellow prisoners were put in stocks and held in the fortress. Then they were sent to Batavia (now Jakarta) for the first part of the trip back to England. During a seven-week stay in Batavia on a Dutch East India Company ship, most prisoners, including Heywood, were allowed on deck only twice. On December 25, 1791, they were taken aboard a Dutch ship, Vreedenberg. This ship would take them to Europe via Cape Town. Still in Captain Edwards's care, the prisoners were kept in irons for most of the way. At the Cape, they were finally moved to a British warship, HMS Gorgon. This ship sailed for England on April 5, 1792. On June 19, the ship arrived in Portsmouth. The prisoners were moved to the guardship HMS Hector.

In Portsmouth

Bligh had landed in England on March 14, 1790, to public praise. He was quickly promoted to post-captain. In the following months, he wrote his story of the mutiny. On October 22, he was honorably cleared at a court martial for losing the Bounty. In early 1791, he was chosen to lead a new breadfruit trip. This trip left London on August 3, before any news of Heywood's capture reached London. Bligh would be gone for over two years. So, he would not be at the court martial for the returned mutineers.

After Heywood arrived in Portsmouth, his family sought help from their many influential friends. They worked to get the best lawyers. His older sister, Hester ("Nessy"), was most active. She gave her brother full support. On June 3, she wrote to him: "If the events of that day were as Mr. Bligh said, I am so sure of your worth and honor that I will bet my life on your innocence." Heywood sent his personal story of the mutiny to the Earl of Chatham. He was the First Lord of the Admiralty and brother to the prime minister, William Pitt. Heywood later regretted this step. He had not talked to his lawyers. His story had statements that Heywood later said were "errors of an imperfect memory."

On June 8, Nessy was told by her and Heywood's uncle, Captain Thomas Pasley, that Heywood seemed to be "the greatest culprit of all, Christian alone excepted." Pasley said he had "no hope of his not being condemned." Later, Pasley could offer some comfort. Captain George Montagu of Hector, where Heywood was held, was Pasley's "particular friend." By chance, another Heywood naval relative, Captain Albemarle Bertie, was in Portsmouth Harbour. His ship HMS Edgar was next to Hector. Mrs. Bertie and Edgar's officers often visited Heywood. They brought gifts of food, clothing, and other comforts.

Pasley hired Aaron Graham, a skilled lawyer, to lead Heywood's legal plan. Between June and September, Heywood and his sister exchanged many letters and poems. Nessy's last letter, just before the court martial, urged: "May the Almighty Providence... be still your bountiful Protector! May he put into the hearts of your judges every feeling of justice, generosity and compassion... and may you at last be restored to us."

The Court Martial

The court martial began on September 12, 1792. It was held aboard HMS Duke in Portsmouth Harbour. Heywood was accused along with Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh, and Charles Norman. These three had been cleared in Bligh's account and expected to be found innocent. Michael Byrne, the nearly blind ship's fiddler, also expected to be cleared. The other accused were James Morrison, Thomas Burkitt, Thomas Ellison, John Millward, and William Muspratt.

The court martial board was led by Lord Hood. He was the naval commander-in-chief at Portsmouth. The board also included Pasley's friend George Montagu and Heywood's relative, Albemarle Bertie.

The testimonies of boatswain Cole, carpenter Purcell, and sailing master John Fryer were not against Heywood. However, Thomas Hayward's statement that Heywood was with the mutineers was damaging. So was John Hallett's evidence about Heywood's supposed disrespect in laughing at Bligh. Hallett had previously written to Nessy Heywood saying he knew nothing about Heywood's part in the mutiny.

Heywood started his defense on September 17, 1792. One of his lawyers read a long, prepared statement. It began by admitting his difficult situation. To be accused of mutiny was to "appear at once the object of unpardonable guilt." His case was based on several arguments. Historian Caroline Alexander points out these arguments were not always consistent.

First, Heywood said his "extreme youth and inexperience" caused him to fail to join Bligh and the loyalists. He said he was "influenced... by the Example of my Messmates, Mr. Hallet and Mr. Hayward." He claimed Hayward, though experienced, cried when Christian ordered him into the boat. Heywood then gave a different reason for staying on the Bounty. He said Bligh's boat was too full. Any more people would have destroyed it. Finally, Heywood said he had planned to join Bligh but was stopped. He said he told Mr. Cole he would get things and follow him into the boat, but "was afterwards prevented."

Under more questions, Cole confirmed he believed Heywood was held against his will. William Peckover, Bounty's gunnery officer, said if he had stayed to retake the ship, he would have looked to Heywood for help. Witnesses from the Pandora said Heywood had given himself up willingly. They also said he was very helpful in giving information. On the issue of his laughing at Bligh, Heywood questioned Hallett's testimony. He asked how Hallett could "particularise the muscles of a man's countenance" from a distance during the chaos of a mutiny. Heywood ended his defense by saying that if Bligh had been in court, he would have "exculpated me from the least disrespect."

Verdict and Sentences

On September 18, 1792, Lord Hood announced the court's decisions. As expected, Coleman, McIntosh, Norman, and Byrne were found innocent. Heywood and the other five were found guilty of mutiny. They were ordered to be hanged. Lord Hood added: "Considering various circumstances, the court humbly and very strongly recommended the said Peter Heywood and James Morrison to His Majesty's Royal Mercy." Heywood's lawyer, Aaron Graham, quickly told his family that the young man's life was safe and he would soon be free.

As weeks passed, Heywood calmly studied the Tahitian language. Meanwhile, his family, especially Nessy, worked hard for him. Another plea was made to the Earl of Chatham in very emotional terms. Soon after, there was a sign that a royal pardon was coming. On October 26, 1792, on Hector's quarterdeck, Captain Montagu formally read the pardon to Heywood and Morrison. Heywood replied with a short statement. It ended: "I receive with gratitude my Sovereign's mercy, for which my future life will be faithfully devoted to his service." A Dutch newspaper reported that his regret was shown with "a flood of tears." William Muspratt, the only other accused person to use a lawyer, was pardoned in February 1793 due to a legal detail.

Three days later, aboard HMS Brunswick, Millward, Burkitt, and Ellison were hanged. Historian Greg Dening called them "a humble remnant on which to wreak vengeance." There was some worry in the press. People suspected that "money had bought the lives of some, and others fell sacrifice to their poverty." A report that Heywood was to inherit a large fortune was not true. Still, Dening states that "in the end it was class or relations or patronage that made the difference." Some accounts say the condemned trio kept saying they were innocent until the very end. Others speak of their "manly firmness that... was the admiration of all."

What Happened Next

On Lord Hood's specific advice, Heywood went back to his naval career. He became a midshipman aboard his uncle Thomas Pasley's ship HMS Bellerophon. In September 1793, Lord Howe, commander of the Channel Fleet, called him to serve on HMS Queen Charlotte. This was the fleet's flagship. Richard Hough notes that a pardon, followed by promotion, for one of Bligh's main targets was "a public rebuke to the absent captain." Everyone knew it.

Bligh had left on his second breadfruit trip in August 1791 as a national hero. But the court martial had shown damaging evidence of his difficult and bossy behavior. The families of Heywood and Christian, seeing how lenient the court was, began their own efforts to clear their names and get revenge on Bligh. When Bligh returned in August 1793, public opinion had turned against him. Lord Chatham, at the Admiralty, refused to see him or his report. Bligh was then left without a job for 19 months before his next assignment.

Soon after his release, Heywood wrote to Edward Christian, Fletcher's older brother. He said he would "try to prove that your brother was not that vile wretch... but, on the contrary, a most worthy character... beloved by all (except one, whose bad report is his greatest praise)." This statement was published in a local newspaper. It went against the respect Heywood had shown Bligh in court. This led to the publication of Edward Christian's Appendix in late 1794. It was presented as an account of the "real causes and circumstances of that Unhappy Transaction." The press said the Appendix tried to "make Christian and the Mutineers look better, and to blame Captain Bligh." In the arguments that followed, Bligh's replies could not stop doubts about his own conduct. His position was further weakened when William Peckover, a Bligh loyalist, confirmed that the claims in the Appendix were mostly true.

Peter Heywood's Later Career

Heywood served on Queen Charlotte until March 1795. He was on board when the French fleet was defeated at Ushant on June 1, 1794. This event is known as the "Glorious First of June". In August 1794, he was promoted to acting lieutenant. In March 1795, any doubts about his right to further promotion as a convicted mutineer were set aside. His promotion to full lieutenant was approved. This was despite him not having the required six years of sea service. Among those who supported his promotion was Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian, a relative of Fletcher Christian.

In January 1796, Heywood was made third lieutenant to HMS Fox. He sailed with her to the East Indies. He stayed in this area for nine years. By the end of 1796, he was Fox's first lieutenant. He remained so until mid-1798 when he moved to HMS Suffolk. On May 17, 1799, Heywood received his first command. This was HMS Amboyna, a brig-of-war. In August 1800, Heywood was made commander of a bomb ship, the Vulcan. In this ship, he visited Coupang, where he had been a prisoner eight years earlier. At this time, he began the hydrographic work that would be a big part of his naval career.

As a Hydrographer

In 1803, after several commands, Heywood was promoted to post-captain. In command of HMS Leopard, Heywood carried out surveys of the eastern coasts of Ceylon and India. These areas had not been studied before. He produced what Caroline Alexander calls "beautifully drafted charts." In later years, he made similar charts for the north coast of Morocco. He also charted the River Plate area of South America, parts of the coasts of Sumatra and northwest Australia, and other channels and coastlines.

His skill in this area may have come from Bligh's teaching. Bligh was a good mapmaker. He had written about Christian and Heywood: "These two had been objects of my particular regard and attention, and I had taken great pains to instruct them." James Horsburgh, who was a hydrographer for the East India Company, wrote that Heywood's work "greatly helped make my Sailing Directory for the Indian navigation much more perfect." Heywood's professional reputation was clear when he was offered the position of Admiralty Hydrographer in 1818. This was after he had retired from the sea. He turned it down. The job went to Francis Beaufort on Heywood's recommendation.

Captain Heywood took command of HMS Dedaigneuse in April 1803 in the East Indies. On December 14, she captured the French privateer Espiegle. Because of his poor health and the death of his elder brother, Captain Heywood left his command on January 24, 1805. He then returned to the United Kingdom as a passenger on the East Indiaman Cirencester.

Later Service

After a short time ashore in 1805–06, Heywood was made flag captain to Rear-Admiral Sir George Murray. He served aboard HMS Polyphemus. In March 1802, Murray's squadron transported troops from the Cape of Good Hope to South America. This was to support a failed British attempt to capture Buenos Aires from the Spanish. The Spanish were allied with the French during the Napoleonic Wars. Polyphemus stayed in the River Plate area. It carried out surveys and protected merchant vessels.

In 1808, Heywood was back in England. He commanded HMS Donegal. The next year, this ship was part of a squadron that attacked and destroyed three French frigates in the Bay of Biscay. He received thanks from the Admiralty for this action. After taking command of HMS Nereus in May 1809, Heywood served briefly in the Mediterranean under Admiral Lord Collingwood. After Collingwood's death in March 1810, Heywood brought his commander's body back to England. He then took Nereus to South America. He stayed there for three years. He earned the thanks of British merchants in that region for protecting trade routes. Heywood's last command was HMS Montagu. In this ship, he escorted King Louis XVIII on his return to France in May 1814. He stayed with Montagu for the rest of his naval service.

Caroline Alexander suggests that throughout his later career, Heywood felt guilty about his pardon. He knew he had "lied" by saying he was kept below deck and could not join Bligh. She believes Pasley and Graham might have paid William Cole to say Heywood was held against his will. This is similar to what Thomas Bond, Bligh's nephew, claimed in 1792. Bond said "Heywood's friends have bribed through thick and thin to save him." John Adams, the last survivor of Christian's Bounty party, was found in 1808. In 1825, Adams said Heywood was on the gangway, not below. He "might have gone [in the open boat] if he pleased."

Retirement and Death

On July 16, 1816, Montagu was taken out of service in Chatham. Heywood finally retired from the sea. Two weeks later, he married Frances Joliffe, a widow he had met ten years earlier. They settled at Highgate, near London. The couple had no children. However, a will he signed in 1810 suggests Heywood also had a British child. The will mentions Mary Gray, "an infant under my care and protection."

In May 1818, Heywood turned down command of the Canadian Lakes with the rank of commodore. He was happy with life on shore. He said he would only accept another job if there was a war. In retirement, Heywood published his dictionary of the Tahitian language. He wrote papers about his profession and corresponded widely. He knew people like the writer Charles Lamb. He was a close friend of the hydrographer Francis Beaufort. He destroyed much of his writing shortly before his death. But a document from 1829 survives. In it, he shares his views on the unsuitability of Greeks, Turks, Spaniards, and Portuguese for self-government. He also wrote about the problems of the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. He also questioned the benefits of Catholic emancipation in Ireland.

Heywood had strong religious beliefs. He became more interested in spiritual matters in his last years. His health began to fail in 1828. He died after having a stroke in February 1831, at age 58. He was buried in the vault of Highgate School chapel. A memorial plaque was placed there on December 8, 2008. He is also remembered on his widow Frances's grave on the west side of Highgate Cemetery.

Nessy Heywood died on August 25, 1793, less than a year after Peter's pardon. Heywood's Bounty opponents John Hallett and Thomas Hayward both died at sea within three years of the court martial. William Bligh fought in the battles of Camperdown and Copenhagen. In 1806, he was made Governor of New South Wales. He returned to London in 1810 after another rebellion by local army officers. They opposed Bligh's attempts to change local practices and his rule by strict orders. Bligh was again court-martialed and cleared. When he retired, he was promoted to rear admiral. He died in 1817. Likewise, his Pandora opponents Edward Edwards died in 1816 and Lt John Larkin died in 1830. William Muspratt died in Royal Navy service in 1797, as did James Morrison in 1807. Fletcher Christian, who took the Bounty to Pitcairn Island and started a colony there, was killed in September 1793 during a fight. Christian's last words were supposedly "Oh, dear!"

Images for kids

-

HMS Pandora, wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef; an etching based on a sketch by Peter Heywood.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |