Parrot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids ParrotsTemporal range: Eocene – Recent

54 mya – present |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| (unranked): |

Psittacopasserae

|

| Order: |

Psittaciformes

Wagler, 1830

|

| Superfamilies | |

|

Cacatuoidea (cockatoos) |

|

|

|

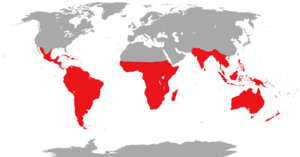

| Range of Parrots, all species (red) | |

Parrots are amazing birds found in warm, tropical, and subtropical parts of the world. They belong to a group called Psittaciformes. These birds are super smart! They have big brains, can learn new things, and some can even use simple tools. Many people love parrots as pets because they can copy human voices and have bright, colorful feathers.

Contents

What Makes a Parrot Special?

Parrots have a strong, compact body with a large head and a short neck. Their beaks are short, very strong, and curved. They use their powerful beaks to crack open tough fruits and seeds. Parrots also have a large, strong tongue.

Their legs are strong, and their feet are special! They have two toes pointing forward and two toes pointing backward. This helps them climb trees easily. Many parrots are very colorful, with feathers of many different shades. Cockatoos, a type of parrot, are usually white or black. They have a cool crest of feathers on their heads that they can move up and down. Most parrots look pretty similar whether they are male or female.

Types of Parrots

Parrots are divided into three main groups:

- The true parrots (Psittacoidea)

- The cockatoos (Cacatuoidea)

- The New Zealand parrots (Strigopoidea)

You can find the most different kinds of parrots in South America and a region called Australasia (which includes Australia and nearby islands).

How Parrots Behave

Studying parrots in the wild can be tricky! They are hard to catch, and if you put a tag on them, they often chew it off. Parrots also fly over large areas, so we don't know everything about their behavior.

Some parrots fly very fast and straight. Most spend a lot of time sitting or climbing in the tops of trees. They often use their beaks like an extra hand to grip branches while climbing. When they are on the ground, parrots often walk with a bit of a waddle.

What Parrots Eat

Parrots eat many different things like seeds, fruit, nectar (sweet liquid from flowers), pollen, and buds. Sometimes they even eat small insects or other tiny animals. For most true parrots and cockatoos, seeds are the most important food. Their strong beaks are perfect for opening tough seeds.

Most true parrots use the same trick to get the seed out of its shell: they hold the seed with their beak, crush the shell with their lower jaw, then turn the seed to remove the rest of the shell. They might even use their foot to hold bigger seeds.

Parrots often eat fruit just to get to the seeds inside. Seeds can have natural chemicals that protect them from being eaten. So, parrots are careful to remove the outer layers of seeds and fruits that might have these chemicals. Many parrots in places like the Americas, Africa, and Papua New Guinea eat clay. This clay can give them minerals and help absorb any bad stuff from their food.

Some parrots, like lories and lorikeets, mostly drink nectar and eat pollen. They have special brush-tipped tongues to collect it. Other parrots also drink nectar when they can find it.

A few parrot species hunt animals, especially insect larvae. For example, Golden-winged parakeets eat water snails. The New Zealand kea parrot can sometimes hunt sheep. Another New Zealand parrot, the Antipodes parakeet, goes into the burrows of nesting birds and kills the adults. Some cockatoos and the New Zealand kaka dig into branches and wood to find grubs (insect larvae).

Parrot Reproduction and Life Cycle

Parrots make their nests in holes or hollows and only protect the area right around their nest. Parrot pairs stay together for a long time, even when they join bigger groups outside of breeding season. Before they mate, parrots do a special dance or display. For cockatoos, these displays are quite simple. True parrots often do a "parade" or "stately walk," and the male might do an "eye-blaze," where his eye pupil gets very small to show the edge of his iris.

Almost all parrots and cockatoos nest in holes. These can be hollows in trees, or holes they dig into cliffs, banks, or the ground. Using holes in cliffs is more common in the Americas. Many species use termite nests, possibly to hide their nests or to keep them at a good temperature. Usually, both parents help dig the nest hole. The length of the burrow can be from about 0.5 to 2 meters (1.6 to 6.6 feet) long. Cockatoo nests are often lined with sticks and wood chips. Some parrots live in huge groups, like the Burrowing parakeet, which can nest in colonies of up to 70,000 birds!

The female parrot stays in the nest for almost the entire time the eggs are incubating (keeping warm). The male feeds her, and she takes short breaks. Incubation lasts from 17 to 35 days. When baby parrots are born, they are helpless. They either have no feathers or just a few sparse white ones. The young stay in the nest for three weeks to four months, depending on the species. Their parents might continue to care for them for several months after they leave the nest.

Larger parrots, like macaws, usually have only one or a few babies each year, and they might not breed every year.

Parrot Intelligence and Learning

Parrots are considered some of the smartest birds, right up there with crows, ravens, and jays. Scientists have seen parrots show their intelligence by learning to use words. Some parrots, like the kea, are also very good at using tools and solving puzzles.

Learning when they are young is very important for all parrots. Much of what they learn comes from watching and interacting with other parrots, especially their siblings. They usually learn how to find food from their parents. Playing is also a big part of how parrots learn. They might have play fights or practice flying wildly to learn how to escape from predators.

Sound Imitation and Speech

Many parrots can copy human speech and other sounds. A scientist named Irene Pepperberg studied a grey parrot named Alex. Alex learned to use words to identify objects, describe them, count them, and even answer tricky questions like "How many red squares?" He was right over 80% of the time! Another grey parrot named N'kisi learned about a thousand words and could even make up new words and use them correctly.

Grey parrots are famous for how well they can copy sounds and human speech. This has made them popular pets for a very long time.

Even though most parrot species can imitate sounds, some amazon parrots are considered the next best at speaking. We don't fully know why birds imitate, but those that do often score very high on problem-solving tests. Wild grey parrots have even been seen copying other birds.

Parrots as Pets

Parrots might not be the best pets for everyone because of their natural wild behaviors, like screaming and chewing. While young parrots can be very sweet, they can become aggressive when they grow up, especially if they aren't handled well. They might bite, which can cause serious injury.

The small budgerigar, or "budgie," is the most popular pet bird species.

Pet parrots can live in a cage or a large aviary. Tame parrots should also be allowed out regularly to play on a stand or a special "gym."

Some common pet parrot species include conures, macaws, amazon parrots, cockatoos, greys, lovebirds, cockatiels, budgerigars, caiques, and Eclectus, Pionus, and Poicephalus species.

Parrots need a lot of attention, care, and things to keep their minds busy. It's like taking care of a three-year-old child! Many people find it hard to provide this much care for a long time. Parrots bred as pets are often hand-fed or taught to interact with people from a young age so they become tame. However, even hand-fed parrots can become aggressive during certain times or if they are not handled well. Parrots are not easy pets. They need proper food, grooming, vet care, training, toys to play with, exercise, and social time with other parrots or humans to stay healthy.

How Long Parrots Live

Some large parrot species, like big cockatoos, amazons, and macaws, can live for a very long time. Some have been reported to live 80 years, and a few have lived over 100 years! Smaller parrots, like lovebirds and budgies, have shorter lives, usually up to 15–20 years.

Protecting Parrots

Many wild parrot populations have shrunk because people catch them for the pet trade. Other reasons include hunting, losing their natural homes, and competition from invasive species (new species that move into an area). Parrots are more affected by these problems than any other group of birds. Efforts to protect the homes of some well-known parrot species have also helped many other less famous species living in the same areas.

Interesting Facts About Parrots

- There are about 372 different species of parrots.

- The most different kinds of parrots live in South America and Australasia.

- The smallest parrot is the Buff-faced pygmy parrot, which weighs only about 11.5 grams (0.4 ounces) and is about 8.6 centimeters (3.4 inches) long.

- The hyacinth macaw is the longest parrot species, but half of its length is its tail!

- Parrot eggs are always white.

- Some grey parrots have shown they can understand what words mean and put together simple sentences.

- Parrots have a brain-to-body size ratio similar to that of higher primates (like monkeys and apes).

- Parrots don't have vocal cords. They make sounds by pushing air across a special organ called the syrinx in their windpipe. They change the depth and shape of their windpipe to make different sounds.

- The oldest known parrot fossils, found in Europe, are about 50 million years old.

Images for kids

-

Fossil jawbone specimen UCMP 143274, thought to be from an early parrot or a dinosaur called an oviraptorosaur

-

Fossil skull of a presumed parrot relative from the Eocene Green River Formation in Wyoming

-

Glossy black cockatoo showing the parrot's strong bill, clawed feet, and sideways-positioned eyes

-

Eclectus parrots, male left and female right

-

Most parrot species live in warm places, but some, like this austral parakeet, live in cooler areas.

-

The kea is the only parrot that lives in snowy mountains.

-

Hyacinth macaws were taken from the wild for the pet trade in the 1980s. Because of this, Brazil now has very few breeding pairs left in the wild.

-

Wild red-masked parakeets in San Francisco

-

The Norfolk kaka became extinct in the mid-1800s because of too much hunting and losing its home.

-

A preserved specimen of the Carolina parakeet, which was hunted until it became extinct.

See also

In Spanish: Psitaciformes para niños

In Spanish: Psitaciformes para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |