Romanesque art facts for kids

Romanesque art was a popular art style in Europe from about 1000 AD until the Gothic style began in the 12th century. The time before it was called the Pre-Romanesque period. Experts in the 1800s created the name "Romanesque" because the architecture, especially, looked a lot like old Roman architecture. It used round arches, barrel vaults, and apses, but it also had many new ideas.

Romanesque art was the first art style to spread across all of Catholic Europe, from Sicily to Scandinavia. It was also greatly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting. The energetic decorations from Insular art in the British Isles also played a big role. All these influences came together to create a new and unique style.

Contents

What Makes Romanesque Art Special?

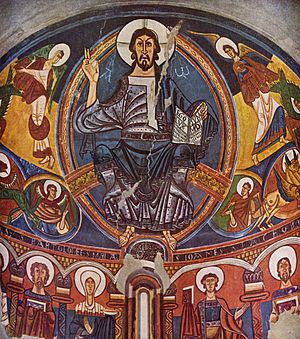

Beyond buildings, Romanesque art had a strong and lively style in both sculpture and painting. Paintings in churches often followed Byzantine ideas for common subjects. These included Christ in Majesty (Jesus on his throne), the Last Judgment, and scenes from Jesus's life.

More original ideas appeared in illuminated manuscripts (decorated books). This was because artists needed to show new scenes. The most beautifully decorated books were bibles and psalters (books of psalms). Column capitals (the tops of columns) were also very creative. They often had full scenes carved into them with many figures.

Large wooden crucifixes (crosses with Jesus's body) were a German idea from the start of this period. Free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna (Mary on a throne) also became popular. Most sculptures were in high relief, meaning they stuck out a lot from the background.

Colours in Romanesque art were very bright and mostly primary (red, blue, yellow). Today, we can usually only see these original vivid colours in stained glass and well-preserved manuscripts. Stained glass became widely used, but not many pieces have survived.

A new invention of this time was the carved tympanum above church doorways. These large carvings often showed Christ in Majesty or the Last Judgement. Artists had more freedom with these than with paintings, as there were no old Byzantine examples to copy.

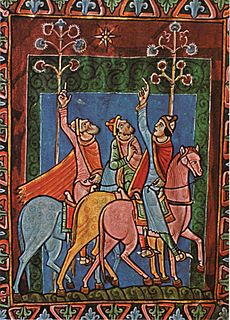

Artworks usually had little depth. Figures often varied in size, with more important figures shown larger. Landscape backgrounds were rare and looked more like abstract patterns than real places. The trees in the "Morgan Leaf" are a good example. Portraits of real people were almost non-existent.

Why Did Romanesque Art Appear?

During this time, Europe became richer. High-quality art was no longer just for kings and a few monasteries, as it had been in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. Monasteries were still very important, especially new orders like the Cistercian, Cluniac, and Carthusian monks, who spread across Europe.

But city churches, churches on pilgrimage routes, and many churches in small towns were also beautifully decorated. These smaller churches often survived, while bigger cathedrals in cities were rebuilt later. No Romanesque royal palaces have survived.

Artists who were not monks or priests became more valued. Many masons (stone carvers) and goldsmiths were now lay people. Lay painters, like Master Hugo, were common, especially for the best artworks, by the end of the period. These artists likely worked with church leaders to decide what to show in their art.

Amazing Romanesque Sculpture

Metalwork, Enamels, and Ivories

Precious objects made from metal, enamel, and ivory were highly valued during this time, perhaps even more than paintings. We know the names of more artists who made these objects than those who painted or carved stone. Metalwork, often decorated with enamel, became very advanced.

Many impressive shrines built to hold holy relics still exist. The most famous is the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral by Nicholas of Verdun and others (around 1180–1225). The Stavelot Triptych and Reliquary of St. Maurus are other examples of beautiful Mosan enamel work. Large reliquaries and altar frontals were built around a wooden frame. Smaller boxes were made entirely of metal and enamel. A few everyday items like mirror cases and jewellery also survived.

The bronze Gloucester candlestick and the brass font from 1108–1117 in Liège are excellent examples of metal casting. The candlestick is very detailed and energetic, inspired by manuscript art. The font shows the Mosan style at its most classic and grand. Other important metal pieces include the bronze doors at Hildesheim Cathedral, the Gniezno Doors, and the doors of the Basilica di San Zeno in Verona.

The aquamanile, a container for washing hands, first appeared in Europe in the 11th century. Artists often shaped them like fantastic zoomorphic (animal-like) creatures. Most surviving examples are made of brass.

The Cloisters Cross is a very large ivory crucifix with complex carvings. It has many figures of prophets and others. It is thought to be by Master Hugo, one of the few known artists, who also decorated manuscripts. Like many pieces, it was originally partly coloured. The Lewis chessmen are well-preserved examples of small ivory carvings. Many other small ivory pieces, like parts of croziers (bishop's staffs) and plaques, also remain.

Sculpture on Buildings

After the Western Roman Empire fell, the tradition of carving large stone statues and bronze figures mostly disappeared. It also stopped in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) world for religious reasons. Some life-size sculptures were made from stucco or plaster, but few have survived.

The most famous large sculpture from early Romanesque Europe is the life-size wooden Crucifix. It was ordered by Archbishop Gero of Cologne around 960–965. This became a very popular type of artwork. Later, these crucifixes were placed on a beam above the chancel arch, called a rood. From the 12th century, they were often joined by figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, figure sculpture strongly returned. Carved reliefs on buildings became a key feature of the later Romanesque period.

Styles and Inspirations

Figurative sculpture (sculpture showing figures) was inspired by two main sources: illuminated manuscripts and small ivory or metal sculptures. Some experts also suggest that the large carved friezes on Armenian and Syriac churches were an influence.

These sources led to a unique style that can be seen across Europe. However, the most impressive sculpture projects are found in South-Western France, Northern Spain, and Italy.

Images in metalwork were often embossed (raised from the surface). This created a surface with two main levels, and details were usually carved into it. This style was then used for stone carving, especially on the tympanum above church doorways. Here, images of Christ in Majesty with symbols of the Four Evangelists were copied directly from the gold covers or decorated pages of medieval Gospel Books. This type of doorway was common and continued into the Gothic period.

In South-Western France, many impressive examples have survived. These include Saint-Pierre in Moissac, Souillac, and La Madeleine, Vézelay. All these were "daughter houses" (churches connected to) of Cluny. They have many other sculptures in their cloisters and other buildings. Nearby, Autun Cathedral has a Last Judgement carving that is special because its creator, Giselbertus, signed it.

Figures in illuminated manuscripts often had to fit into small spaces, so they were twisted or bent to fit. Artists used this skill to design figures for doorposts, lintels, and other parts of buildings. The clothes of painted figures were often flat and decorative, not looking like real fabric. This style was also used in sculpture. A great example is the figure of the Prophet Jeremiah from the pillar of the portal at the Abbey of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, France, from about 1130.

One of the most important patterns in Romanesque art, found in both figure and non-figure sculpture, is the spiral. One source might be Ionic capitals (the tops of columns with scroll shapes). Scrolling vines were a common pattern in Byzantine and Roman art. They can be seen in mosaics from the 4th-century Church of Santa Costanza, Rome. Manuscripts and carvings from the 12th century have very similar scrolling vine patterns.

Another source of the spiral pattern is the illuminated manuscripts from the 7th to 9th centuries, especially Irish manuscripts like the St. Gall Gospel Book. These were brought to Europe by Irish and Scottish missionaries. In these books, the spiral was an abstract, mathematical pattern, not related to plants. This style was then picked up in Carolingian art and given a more plant-like look. This adapted spiral pattern appears in the clothing of both sculptures and stained glass windows. A great example is the central figure of Christ at La Madeleine, Vezelay.

Another influence from Insular art is the use of animals that are connected or intertwined. These were often used beautifully on column capitals (like at Silos) and sometimes on the columns themselves (like at Moissac). Many Romanesque decorations with paired, facing, or intertwined animals have similar Insular origins. This also applies to animals whose bodies turn into purely decorative shapes.

What Did Romanesque Sculpture Show?

Most Romanesque sculpture tells a story from the Bible. Many different themes are found on column capitals. These include scenes from the Creation and the Fall of Man. There are also stories from the life of Christ and Old Testament scenes that foreshadow his Death and Resurrection. Examples include Jonah and the Whale and Daniel in the lions' den.

Many Nativity (birth of Jesus) scenes appear, with the theme of the Three Kings being very popular. The cloisters (covered walkways) of Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey in Northern Spain and Moissac are excellent, complete examples. The relief sculptures on the many Tournai fonts found in churches in southern England, France, and Belgium are also fine examples.

Some Romanesque churches have large sculptural designs covering the area around the main doorway, or even much of the front of the building. Angouleme Cathedral in France has a very detailed sculpture plan set within the arches of its facade. In Catalonia (Spain), an elaborate picture story in low relief surrounds the door of the church of Santa Maria at Ripoll.

The goal of these sculptures was to teach Christian believers. They aimed to show that people should recognize their wrongdoings, feel sorry for them, and be saved. The Last Judgement reminds believers to repent. The carved or painted Crucifix, placed clearly inside the church, reminds sinners of salvation.

Often, the sculptures look strange or even scary. These works are found on capitals, corbels (support brackets), and bosses (decorative knobs), or woven into the patterns on door frames. They show forms that are hard to understand today. Common images include Sheela na Gig (a female figure), fearsome demons, ouroboros (dragons eating their tails), and many other mythical creatures with unclear meanings. Spirals and paired patterns originally had special meanings in old stories that are now lost.

A common theme on capitals from this period is a person being beaten by their wife or grabbed by demons. Demons fighting over the soul of a wrongdoer, like a greedy person, was another popular subject.

Late Romanesque Sculpture

Gothic architecture is usually thought to have started with the design of the choir at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, in 1144. Gothic sculpture is usually dated a little later, with the carving of figures around the Royal Portal at Chartres Cathedral, France, from 1150–1155.

The new style of sculpture spread quickly from Chartres, even faster than the new Gothic architecture. Many churches built in the late Romanesque period were actually built after Saint-Denis. This sculptural style, which focused more on looking at real life and natural forms than on strict designs, developed quickly.

One reason for this fast change to natural forms might have been a growing interest in old Roman and Greek art. Artists in places with many classical ruins started to copy their style. This means some doorways look Romanesque in shape but show the naturalism of early Gothic sculpture.

One example is the Pórtico da Gloria (Portico of Glory) from 1180, at Santiago de Compostela. This doorway is inside the building and is very well preserved. It even still has colour on the figures, showing how brightly painted much Romanesque art once was. Around the doorway are figures that are part of the small columns forming the door frame. They are three-dimensional but slightly flattened. They look very individual, not just in how they appear but also in their expressions. They look quite similar to the figures around the north porch of the Abbey of St. Denis, from 1170. Below the main carving, there is a realistic row of figures playing different, easily recognizable musical instruments.

Romanesque Painting

Decorating Books (Manuscript Illumination)

Several regional styles came together in early Romanesque illuminated manuscripts. The "Channel school" in England and Northern France was heavily influenced by late Anglo-Saxon art. In Southern France, the style was more influenced by Spain. In Germany and the Low Countries, Ottonian styles continued to develop and, along with Byzantine styles, influenced Italy. By the 12th century, all these styles had influenced each other, though each region kept its own unique look.

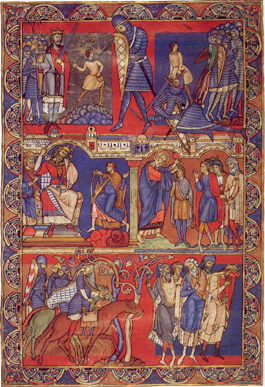

Romanesque artists mainly decorated Bibles and Psalters. In Bibles, each book might start with a large historiated initial (a letter with a picture inside). In Psalters, important initial letters were also decorated. More elaborate books might have full pages of scenes, sometimes with several scenes on one page, in separate sections. Bibles, especially, were often very long and might be bound into more than one volume.

Examples include the St. Albans Psalter, Hunterian Psalter, Winchester Bible (the "Morgan Leaf" shown above), Fécamp Bible, Stavelot Bible, and Parc Abbey Bible. By the end of the period, workshops run by lay (non-religious) artists and scribes became important. Books and their decorations became more widely available to both ordinary people and clergy.

Wall Paintings

The large, flat walls and curving ceilings of Romanesque buildings were perfect for mural (wall) decoration. Sadly, many of these early wall paintings have been destroyed by dampness or covered over with new plaster and paint. In England, France, and the Netherlands, such pictures were often destroyed or whitewashed during the Protestant Reformation.

However, murals in Denmark, Sweden, and other places have since been restored. In Catalonia (Spain), there was a project in the early 1900s to save these murals by removing them and moving them to safety in Barcelona. This resulted in the amazing collection at the National Art Museum of Catalonia. In other countries, paintings suffered from wars, neglect, and changing tastes.

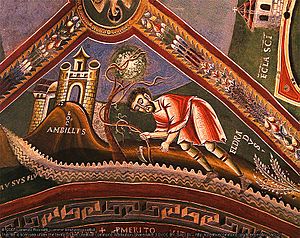

A typical plan for decorating a church with paintings, based on earlier mosaic examples, had a main focus in the semi-dome of the apse (the curved end of the church). This usually showed Christ in Majesty or Christ the Redeemer sitting on a throne inside a mandorla (an almond-shaped halo). He was framed by the four winged beasts, which are symbols of the Four Evangelists. This directly compares to the gold covers or decorated pages of Gospel Books from the period. If the Virgin Mary was the church's patron saint, she might be shown here instead of Christ.

On the apse walls below, there would be saints and apostles. There might also be story scenes, for example, about the saint the church was named after. On the arch leading to the sanctuary, there were figures of apostles, prophets, or the twenty-four "elders of the Apocalypse." They would look towards a bust of Christ, or his symbol, the Lamb, at the top of the arch. The north wall of the nave (main part of the church) would have stories from the Old Testament. The south wall would have stories from the New Testament. On the back west wall, there would be a Last Judgement, with Christ on his throne judging at the top.

One of the most complete painting schemes still existing is at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe in France. The long, curved ceiling of the nave was perfect for frescoes. It is decorated with scenes from the Old Testament, showing the Creation, the Fall of Man, and other stories. This includes a lively picture of Noah's Ark with a scary figurehead and many windows. Through these windows, you can see Noah and his family on the top deck, birds on the middle deck, and pairs of animals on the lower deck. Another scene powerfully shows Pharaoh's army being swallowed by the Red Sea. The paintings continue in other parts of the church, with the martyrdom of local saints shown in the crypt and the Apocalypse in the narthex. The colours used are limited to light blue-green, yellow ochre, reddish-brown, and black. Similar paintings exist in Serbia, Spain, Germany, Italy, and other parts of France.

The now-scattered paintings from Arlanza in the Province of Burgos, Spain, are from a monastery but show everyday subjects. They feature huge, energetic mythical beasts above a black and white pattern with other creatures. They give us a rare idea of what decorated Romanesque palaces might have looked like.

Other Romanesque Art Forms

Embroidery

Romanesque embroidery is best known from the Bayeux Tapestry in Bayeux, France, or the Tapestry of Creation in Girona, Spain. However, many more detailed pieces of Opus Anglicanum ("English work"—considered the finest in the West) and other styles have survived, mostly as church vestments (special clothes for priests).

Stained Glass

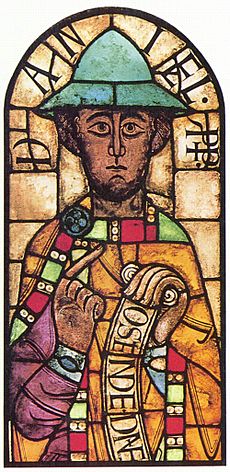

The oldest known pieces of medieval stained glass with pictures seem to be from the 10th century. The earliest complete figures are five prophet windows at Augsburg, from the late 11th century. The figures are stiff and formal, but they show great skill in design. This suggests the artist was very familiar with working with glass.

At Le Mans, Canterbury and Chartres Cathedrals, and Saint-Denis, several panels from the 12th century have survived. At Canterbury, these include a figure of Adam digging and another of his son Seth from a series of Ancestors of Christ. Adam looks very natural and lively, while in the figure of Seth, the robes are used for great decorative effect, similar to the best stone carving of the period.

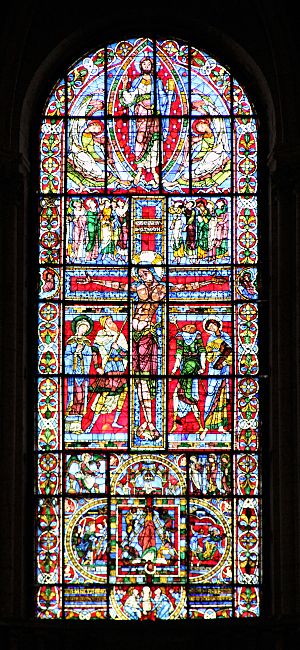

Glass artists were slower to change their style than architects. Much glass from at least the early 13th century can still be considered Romanesque. Especially beautiful are large figures from 1200 at Strasbourg Cathedral (some now in a museum) and from about 1220 at Saint Kunibert's Church in Cologne.

Most of the magnificent stained glass in France, including the famous windows of Chartres, are from the 13th century. Far fewer large windows from the 12th century remain complete. One such is the Crucifixion of Poitiers. This is a remarkable design that rises through three sections. The lowest has a quatrefoil (four-lobed shape) showing the Martyrdom of St Peter. The largest central section is dominated by the crucifixion. The upper section shows the Ascension of Christ in a mandorla. The figure of the crucified Christ already shows the Gothic curve. This window is described as being of "unforgettable beauty."

Many separate pieces are in museums. A window at Twycross Church in England is made up of important French panels saved from the French Revolution. Glass was expensive and could be moved or rearranged. It seems to have been often reused when churches were rebuilt in the Gothic style. The earliest dated English glass, a panel in York Minster from a Tree of Jesse (probably before 1154), was recycled in this way.

See also

In Spanish: Arte románico para niños

In Spanish: Arte románico para niños

- List of Romanesque artists

- Spanish Romanesque