Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson |

|

|---|---|

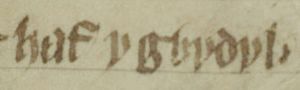

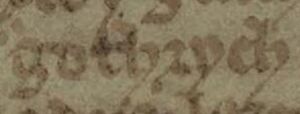

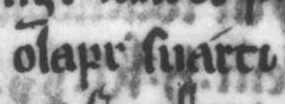

Rǫgnvaldr's name and title as it appears on folio 154r of Oxford Jesus College 111 (the Red Book of Hergest): "Reinaỻt urenhin yr ynyssed".

|

|

| King of the Isles | |

| Reign | 1187–1226 |

| Predecessor | Guðrøðr Óláfsson |

| Successor | Óláfr Guðrøðarson |

| Died | 14 February 1229 Tynwald |

| Burial | St Mary's Abbey, Furness |

| Issue | Guðrøðr Dond |

| House | Crovan dynasty |

| Father | Guðrøðr Óláfsson |

Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson (died 14 February 1229) was a powerful ruler known as the King of the Isles. He reigned from 1187 to 1226. Rǫgnvaldr was the oldest son of Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Dublin and the Isles. Even though his father might have wanted his younger brother, Óláfr, to be king, the people of the Isles chose Rǫgnvaldr. He was likely Óláfr's half-brother. Rǫgnvaldr ruled the Kingdom of the Isles for nearly 40 years before Óláfr took control.

During Rǫgnvaldr's time, the Crovan dynasty was very strong. He was called "the greatest warrior in the western lands" by a Scandinavian writer. He helped William I, King of Scotland in battles and even took over Caithness for a short time. Rǫgnvaldr also had strong ties with the rulers of northern Wales. His daughter was set to marry Rhodri ab Owain, a prince from Gwynedd. In 1193, Rǫgnvaldr sent soldiers to help Rhodri. He was also involved in Irish politics, as he was the brother-in-law of John de Courcy, a powerful English lord.

Rǫgnvaldr often showed loyalty to the English kings, John, King of England and Henry III, King of England. In return, they promised to help him protect his kingdom. Rǫgnvaldr also agreed to protect English interests in the Irish Sea. But when Norway became stronger, Rǫgnvaldr had to show loyalty to Ingi Bárðarson, King of Norway after a Norwegian attack in 1210. He even asked Pope Honorius III for protection in 1219, promising to pay a yearly fee.

Óláfr was given the islands of Lewis and Harris to rule. But he wanted more land. Rǫgnvaldr had him captured and imprisoned by the Scots for almost seven years. After Óláfr was freed, Rǫgnvaldr arranged for him to marry his own wife's sister. Óláfr later ended this marriage and married the daughter of a Scottish leader. This led to a war between the half-brothers in the 1220s. Óláfr's victories forced Rǫgnvaldr to seek help from Alan fitz Roland, Lord of Galloway. Rǫgnvaldr married his daughter to Alan's son, Thomas. But the people of Mann didn't want a king from Galloway, so they chose Óláfr instead. Rǫgnvaldr was killed in battle against Óláfr on 14 February 1229. He was buried at St Mary's Abbey, Furness.

Contents

- Early Life and Becoming King

- Conflicts with Brother Óláfr

- Alliances with Scotland

- Welsh Connections

- Involvement in Ireland

- Ties with English Kings

- Divided Loyalties: England and Norway

- Lasting Ties with England

- Under the Pope's Protection

- Family Reunions and Scottish Plans

- Civil War and Family Strife

- Church Disputes

- Alliance with Alan of Galloway

- Final Battle and Death

Early Life and Becoming King

Rǫgnvaldr was a son of Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Dublin and the Isles. He was part of the Crovan dynasty. In the mid-1100s, Rǫgnvaldr's father, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, became King of the Isles. This kingdom included the Hebrides and the Isle of Man.

His father soon faced trouble from his brother-in-law, Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll. Somairle took control of part of the kingdom in 1153. Three years later, he took over the entire kingdom until he died in 1164. Guðrøðr Óláfsson got his kingdom back. But the lands lost to Somairle stayed with his family, known as the Meic Somairle.

Guðrøðr Óláfsson had one daughter, Affrica, and at least three sons: Ívarr, Óláfr, and Rǫgnvaldr. Óláfr's mother was Findguala Nic Lochlainn, an Irishwoman. She married Guðrøðr Óláfsson around 1176 or 1177, when Óláfr was born.

When Guðrøðr Óláfsson died in 1187, the Chronicle of Mann says he wanted Óláfr to be king. This was because Óláfr was born "in lawful wedlock." However, the people of the Isles chose Rǫgnvaldr instead. He was a strong young man, ready to rule. Óláfr was just a child at the time.

The chronicle suggests that Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr had different mothers. This might explain the big fights between them later on. This family conflict was a major part of Rǫgnvaldr's long reign.

| Simplified family tree of Rǫgnvaldr showing how he was related to the rulers of England, the Isles, Carrick, Galloway, Gwynedd, Kintyre, and Ulster. Rǫgnvaldr and the three Meic Somairle men who could have been the father of his wife are highlighted. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Conflicts with Brother Óláfr

The Chronicle of Mann says Rǫgnvaldr gave Óláfr an island called "Lodhus." The chronicle describes it as rocky and not good for farming. It said the people there lived by hunting and fishing. "Lodhus" is actually Lewis, the northern part of Lewis and Harris. The chronicle seems to have mixed up the island's parts. It also claimed Óláfr was poor and lived "a sorry life." This might show the chronicle's bias against Rǫgnvaldr's family and in favor of Mann.

Because of this supposed poverty, Óláfr went to Rǫgnvaldr, who was also in the Hebrides. Óláfr demanded more land. Rǫgnvaldr had Óláfr captured and sent to William I, King of Scotland. William kept him in prison for almost seven years. It's possible Rǫgnvaldr acted against Óláfr because Óláfr had asked the Norwegian King for help to become king.

The chronicle says William died in December 1214. Before he died, William ordered all his political prisoners to be released. So, Óláfr was likely imprisoned between 1207 and 1214 or early 1215. After his release, the half-brothers met on Mann. Óláfr then went on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela.

Around 1209, the Annals of Ulster reported that the sons of Ragnall mac Somairle attacked Skye. They killed many people there. We don't know if this attack was related to the killing of Ragnall's brother, Áengus mac Somairle, and his three sons the next year. These events show that the Crovan dynasty wasn't the only one causing trouble in the Isles. The death of Áengus and his sons greatly affected the Meic Somairle family and Rǫgnvaldr's rule.

Alliances with Scotland

Rǫgnvaldr and William of Scotland had friendly relations earlier. William faced many rebellions during his rule. One big problem was Haraldr Maddaðarson, Earl of Orkney and Caithness. Haraldr Maddaðarson had married Hvarflǫð, the daughter of an Earl of Moray. This marriage might have pulled him into conflict with the Scottish king. Haraldr Maddaðarson constantly fought against Scottish and Norwegian royal power in his lands.

In 1196, Haraldr Maddaðarson seemed to control Moray. William managed to regain control and gave Caithness to Haraldr Eiríksson. But Haraldr Maddaðarson defeated Haraldr Eiríksson and took back the earldom. This is when Rǫgnvaldr likely got involved. The Orkneyinga saga says William asked Rǫgnvaldr to help. Rǫgnvaldr gathered an army from the Isles, Kintyre, and Ireland. He went to Caithness and took control.

For the winter, Rǫgnvaldr returned to the Isles, leaving three stewards in Caithness. Haraldr Maddaðarson later murdered one of these stewards. William then forced Haraldr Maddaðarson to surrender. The fact that Haraldr Maddaðarson only regained power after Rǫgnvaldr left suggests Rǫgnvaldr had support in the area.

The English historian Roger de Hoveden also wrote about Rǫgnvaldr's involvement in Caithness. He said Rǫgnvaldr bought Caithness from William after talks with Haraldr Maddaðarson failed. This happened around 1200. Before Rǫgnvaldr's involvement, Roger said Haraldr Maddaðarson got military help from the Isles. If this help came from Rǫgnvaldr's kingdom, it shows how easily alliances could change. If it came from the Meic Somairle, it means Haraldr Maddaðarson was working with Rǫgnvaldr's rivals.

Rǫgnvaldr was related to earlier Orcadian earls through his grandfather's marriage. William might have used Rǫgnvaldr to play one powerful family against another. However, Rǫgnvaldr had no known blood ties to the earls. This could mean he was the first Scottish-backed ruler of Caithness without such a connection. Rǫgnvaldr might have ruled as Earl of Caithness for a short time, but records only show he was appointed to manage the area.

Rǫgnvaldr's help for the Scottish king could be because he was related to Roland fitz Uhtred, Lord of Galloway. Or it could be because they both disliked the Meic Somairle. There was confusion about two men named Máel Coluim in the 1100s. One was Máel Coluim mac Áeda, Earl of Ross. The other was Máel Coluim mac Alasdair, an illegitimate son of Alexander I, King of Scotland. The latter Máel Coluim tried to take the Scottish throne and was related by marriage to Somairle's family. If Hvarflǫð's father was this Máel Coluim, it could explain an alliance between Haraldr Maddaðarson and the Meic Somairle. Such an alliance with Rǫgnvaldr's rivals would explain why the Scottish king used Rǫgnvaldr against Haraldr Maddaðarson.

Welsh Connections

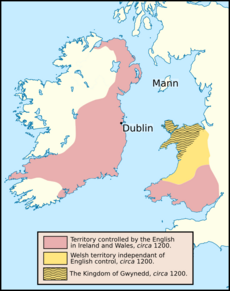

From the start, the Crovan dynasty made alliances with the northern Welsh rulers of the Kingdom of Gwynedd. Rǫgnvaldr's early rule involved him in northern Wales. In the late 1100s, the region had fierce family wars. In 1190, Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd was driven from Anglesey by his brother's sons. The Welsh texts Brenhinedd y Saesson and Brut y Tywysogyon show that Rǫgnvaldr sent military help to Rhodri. This helped Rhodri successfully take back Anglesey three years later. Another Welsh text calls 1193 "the summer of the Gaels" (haf y Gwyddyl). This might refer to Rǫgnvaldr and his soldiers being in Wales.

Rǫgnvaldr and Rhodri also had a marriage alliance. A letter from the Pope in November 1199 says Rǫgnvaldr's daughter was engaged to Rhodri. Rǫgnvaldr's military support for Rhodri in 1193 was almost certainly linked to this. Rhodri died in 1195. The same papal letter says his widow was then arranged to marry his nephew, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Prince of Gwynedd. This arrangement was part of Llywelyn's plan to strengthen his power in Gwynedd. Like his uncle, Llywelyn wanted an alliance with the Islesmen to boost his position in Wales.

This arrangement showed Rǫgnvaldr's power in the region. But Llywelyn later ended the marriage to ally with a stronger power, the English king. Although the marriage between Llywelyn and Rǫgnvaldr's daughter had papal approval in April 1203, it was canceled in February 1205. This was convenient for Llywelyn, who was by then married to Joan, an illegitimate daughter of John, King of England. This might be when Rǫgnvaldr first started his long relationship with the English Crown.

Rǫgnvaldr also helped with Welsh translations of medieval texts about Charlemagne and Roland. Ten manuscripts still exist that contain Cân Rolant, the Welsh version of La chanson de Roland. These, along with Welsh versions of other texts, are part of the Welsh Charlemagne cycle. Most of these manuscripts say Rǫgnvaldr was behind the original translation. This work likely happened after he became king, possibly after his daughter married Rhodri.

The reason for these translations is not clear. During the reign of Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway, many Anglo-Norman manuscripts were translated into Old Norse. Rǫgnvaldr might have learned about these stories in Norway and then asked for his own translations. Or he might have learned about them in England. Rǫgnvaldr's family ties with the Welsh, and possibly church connections between Mann and Wales, might explain his role in the translations. The work was likely done at the Ceredigion monastery of Llanbadarn Fawr, a center for Welsh learning.

Involvement in Ireland

Even though Rǫgnvaldr isn't mentioned in Irish records, other sources show he had Irish connections. For example, Orkneyinga saga says he led a large army from Ireland to help William in Caithness. Also, Henry III ordered Rǫgnvaldr in 1218 to explain "excesses committed upon the people of our Lord the King, as well in England as in Ireland." This means Rǫgnvaldr's men might have caused trouble in Ireland. The poem Baile suthach síth Emhna also talks about his Irish connections. While the poem exaggerates, its claims of raids into Ireland might be true, given Henry III's order.

The poem also hints at Rǫgnvaldr's right to the kingship of Tara and a desire to take power in Dublin. Rǫgnvaldr's ancestors were linked to the Norse-Gaelic Kingdom of Dublin. But when English adventurers took over Dublin in 1170, the Crovan dynasty found itself surrounded by this new English power. Despite their earlier opposition, the dynasty quickly allied with the English. An example is the marriage between Rǫgnvaldr's sister, Affrica, and John de Courcy, a powerful Englishman.

In 1177, Courcy invaded Ulaid (modern County Antrim and County Down). He took Down (now Downpatrick), drove out the king, and ruled his lands independently for about 25 years. The date of Courcy and Affrica's marriage is unknown, but it might have helped his success in Ireland. The rulers of Ulaid and Mann had a difficult past. Courcy's marriage to the Crovan dynasty might have led to his attack on Ulaid. Guðrøðr Óláfsson also formalized his marriage to Findguala in 1176/1177, linking his family to the Meic Lochlainn, another enemy of Ulaid. Courcy likely used these alliances to his advantage, and Guðrøðr Óláfsson used Courcy's campaigns to settle old scores.

Courcy lost power in conflicts with the English king between 1201 and 1204. By 1205, he was forced out of Ireland, and his lands were given to Hugh de Lacy. When Courcy rebelled that year, Rǫgnvaldr helped him. The Chronicle of Mann says Rǫgnvaldr reinforced Courcy's army with 100 ships. They attacked a castle called "Roth" but were defeated when Walter de Lacy arrived. The Annals of Loch Cé also records this expedition. It says Courcy brought a fleet from the Isles to fight the Lacys. The expedition failed, but the invaders plundered the countryside. The castle was almost certainly Dundrum Castle. This defeat in 1205 marked Courcy's downfall; he never regained his Irish lands.

Ties with English Kings

Rǫgnvaldr's involvement in Ireland and his connection to Courcy likely led to his contact with English kings John and Henry III. Courcy's downfall might have been a relief for Rǫgnvaldr. It meant he no longer had to choose between loyalty to the English king and his brother-in-law. On 8 February 1205, John took Rǫgnvaldr under his protection. A year later, John allowed Rǫgnvaldr to come to England. Rǫgnvaldr showed loyalty to John during this visit. John ordered that Rǫgnvaldr be given land worth 30 marks a year. He also ordered 30 marks to be paid to Rǫgnvaldr.

Rǫgnvaldr's growing ties with the English king after Courcy's fall suggest that John wanted to weaken Courcy and prevent further trouble in the Irish Sea. Rǫgnvaldr's marriage alliance with Llywelyn ap Iorwerth also ended around this time. It's possible the English king also arranged this breakup.

In 1210, the Chronicle of Mann reported that John led 500 ships to Ireland. While Rǫgnvaldr and his men were away from Mann, John's forces landed and raided the island for two weeks. They left with hostages. There's no other sign of bad relations between Rǫgnvaldr and John at this time. So, John's attack on Mann was likely not because of Rǫgnvaldr's earlier help for Courcy. Instead, it was probably linked to John's conflicts with the Lacy and Briouze families. In 1208, William de Briouze and his family fled from John to Ireland. The Lacys helped them. When John arrived in Ireland in 1210, the Briouzes fled towards Scotland. They were caught in Galloway by Donnchad mac Gilla Brigte, Earl of Carrick, who was related to Rǫgnvaldr and close to Courcy.

A text from the 1200s, Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d'Angleterre, says the Briouzes stayed on Mann for four days before being captured. It's unclear if Rǫgnvaldr allowed them to stay. But their close ties with the Lacys, and Rǫgnvaldr's ties with Courcy (who the Lacys had driven out), make cooperation unlikely. Other sources confirm the English attacks on Mann. John himself said he learned of the Briouzes' capture while at Carrickfergus. This might mean the attack on Mann was a punishment.

If it was retaliation, it might not have been because of Rǫgnvaldr's own actions. Hugh de Lacy also fled with the Briouzes but escaped capture. He was temporarily hidden in Scotland. The Lacys had connections in Dublin and Ulster. Hugh might have had supporters on Mann. His stay on Mann while Rǫgnvaldr was away might have been possible because of the conflict between Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr.

Divided Loyalties: England and Norway

After the death of Magnús Óláfsson in 1103, Norwegian power in the Isles was weak due to civil war in Norway. But in the mid-1100s, Rǫgnvaldr's father visited Norway and became a vassal of Ingi Haraldsson, King of Norway. A chronicler reported that the kings of the Isles had to pay the Norwegian kings ten marks of gold when a new king took the throne.

In 1210, while loyal to the English king, Rǫgnvaldr became a target of Norway's renewed power in the Isles. The Icelandic annals say a Norwegian military expedition to the Isles was planned in 1209. The next year, they report "warfare" in the Isles and that Iona was plundered. These reports are confirmed by Bǫglunga sǫgur, a saga that says a Norwegian fleet plundered the Isles. It also says "Ragnwald" (King of Möen) and "Gudroder" (King of Manö) had not paid their taxes to the Norwegian kings. As a result, the Isles were ravaged until the two kings went to Norway. They made peace with Ingi Bárðarson, King of Norway and received their lands back as a fief.

The two kings who surrendered in Bǫglunga sǫgur were likely Rǫgnvaldr and his son, Guðrøðr Dond. The tax they paid to Ingi was probably the same tribute mentioned by the chronicler. The Islesmen's surrender happened as the Norwegian king grew stronger and the Crovan dynasty weakened due to internal fights. The destructive Norwegian actions might have been official punishment for Rǫgnvaldr's refusal to pay taxes and his recent alliance with England.

Rǫgnvaldr might have also gone to Norway to protect his kingship from Óláfr's claims. His absence from Mann during the English attack might be explained by this trip. Rǫgnvaldr's surrender to Ingi could have led to the English attack. It might have given the English a reason to devastate Rǫgnvaldr's lands because he had allied with John only a few years before. If this was the case, Rǫgnvaldr's surrender to Norway, though meant to protect his kingdom, had serious consequences.

Lasting Ties with England

Many sources show that Rǫgnvaldr grew closer to the English king after the attacks on Mann and the Isles. For example, on 16 May 1212, Rǫgnvaldr formally swore loyalty to John. This was likely his second visit to England in six years. Records confirm his visit, showing payment for his journey home. They also show the release of some of Rǫgnvaldr's men who had been held in English castles.

On the same day, John ordered his officials in Ireland to help Rǫgnvaldr if his land was threatened by "Wikini or others." This was because Rǫgnvaldr had promised to help John against his enemies. "Wikini" might refer to the Norwegian raiders who plundered the Isles in 1210. This order shows that Rǫgnvaldr was protected by John. It also meant he had to defend John's interests in the Irish Sea. This strengthened Rǫgnvaldr's security and extended John's influence over the Isles.

Also on 16 May, Rǫgnvaldr received a grant of land at Carlingford and yearly corn payments. This was in return for his loyalty and service to the English king. This grant gave Rǫgnvaldr a valuable foothold in Ireland. It also gave his powerful fleet a safe place to dock. The exact location of this land is unknown. Carlingford had been a power center for Hugh de Lacy. Rǫgnvaldr's grant might have filled the power vacuum after Lacy's lands were destroyed.

Rǫgnvaldr's gifts from the English king might have been part of John's plan to counter Philip Augustus, King of France. Around this time, the French king had formed an alliance with Wales. This was to distract the English with a Welsh uprising so they couldn't focus on France. John managed to get support from several foreign lords, including Rǫgnvaldr. But Welsh uprisings and an English revolt kept English forces from invading France.

Because Rǫgnvaldr was loyal to the English king and guarded English sea routes, his men likely caused fewer raids along the English and Irish coasts. Around the same time, several Scottish lords received land grants in northern Ireland. These included three of Rǫgnvaldr's relatives: Alan fitz Roland, Lord of Galloway, his brother Thomas fitz Roland, Earl of Atholl, and Donnchad. These grants were probably part of a plan by the English and Scottish kings to gain control over distant territories.

A record from 3 January 1214 confirms England's intention to protect the Islesmen. It forbade Irish sailors from entering Rǫgnvaldr's lands. The English promises of protection suggest Rǫgnvaldr was under pressure. So, the naval attacks on Derry in 1211/1212 by Thomas fitz Roland and the sons of Ragnall (likely Ruaidrí and Domnall) might have supported Rǫgnvaldr's interests in Ireland. They attacked Derry again in 1213/1214. These raids might have also served Scottish and English interests, aiming to limit Irish support for rebels. If these attacks were against political enemies, Rǫgnvaldr and his forces were likely involved too.

John died in October 1216, and his young son, Henry III, became king. In 1218, Henry III ordered Rǫgnvaldr to fix "excesses" committed by his men in Ireland and England. This could mean Islesmen took advantage of England's troubles by raiding coasts. If so, there's no more evidence of such raids. The "excesses" might also refer to an event where Irish fishermen caused violence on Mann and were killed. Later, Rǫgnvaldr was given safe passage to England to explain his men's actions.

It's unknown if Rǫgnvaldr went to England that year. But he certainly did the next year. He was granted safe passage on 24 September 1219. Records show he swore loyalty to Henry III and received the same land grant John had given him. Henry III added a condition: if enemies rebelled, Rǫgnvaldr had to help defend their lands as long as he remained loyal. So, by 1219, Rǫgnvaldr was again a friendly ally of the English king.

Under the Pope's Protection

In September 1219, while in London, Rǫgnvaldr gave Mann to the papacy. He swore loyalty for the island and promised to pay 12 marks of silver yearly as tribute forever. Pandulf, the Pope's representative in England, accepted Rǫgnvaldr's submission for Pope Honorius III. This kind of submission wasn't new. John had given his kingdom to the papacy six years earlier when he faced a crisis and a French invasion.

The exact reason for Rǫgnvaldr's submission is unclear. It might have been because of the growing power of the Norwegian king. Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway had become king two years earlier, and civil war in Norway was ending. In his submission, Rǫgnvaldr said the kingdom was his by birthright and he owed nothing to anyone. This contradicts Bǫglunga sǫgur, which said he and his son swore loyalty to Hákon and received their kingdom as a fief. So, the submission might have been Rǫgnvaldr's way to free himself from Norwegian rule.

On 23 September 1220, Henry III ordered his officials in Ireland to help Rǫgnvaldr against his enemies. On 4 November 1220, Henry III ordered his men to help Rǫgnvaldr. This was because Rǫgnvaldr had shown proof that Hákon was planning to invade his island kingdom. Soon after this, the Annals of Loch Cé and Annals of the Four Masters reported the death of Diarmait Ua Conchobair in 1221. He was killed by Thomas fitz Roland. These sources say Diarmait was gathering a fleet in the Isles to reclaim the kingship of Connacht. But his actions might have been linked to the Norwegian threat Rǫgnvaldr feared.

Rǫgnvaldr's submission to the Pope might also be linked to his feud with Óláfr. John had appealed to Pope Innocent III to secure his son Henry III's succession. While the timeline of Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr's conflict isn't fully clear, fighting involving Rǫgnvaldr's son broke out in the 1220s. So, Rǫgnvaldr might have wanted to secure his own kingship and his son's future. It's unknown how well Rǫgnvaldr kept his promises to the papacy. Later records suggest his successors didn't continue his commitments. Still, centuries after his death, Rǫgnvaldr's deal with the papacy was remembered in a fresco in the Vatican Archives.

Family Reunions and Scottish Plans

After Óláfr returned from his pilgrimage, the Chronicle of Mann says Rǫgnvaldr had him marry "Lauon," his own wife's sister. Rǫgnvaldr then gave Lewis and Harris back to Óláfr. They lived there until Reginald, Bishop of the Isles arrived. The chronicle says the bishop disapproved of the marriage. A church meeting was held, and the marriage was canceled. The chronicle claimed Óláfr's marriage was wrong because the couple was too closely related. But there's evidence the real reason was the bad feelings between the half-brothers.

For example, Reginald and Óláfr seemed close. The chronicle notes that Reginald was Óláfr's sister's son, and Óláfr welcomed him warmly. Reginald also started the annulment. After the previous Bishop of the Isles died in 1217, Reginald and Nicholas de Meaux, Abbot of Furness competed for the bishop's office. Óláfr seemed to support Reginald, while Rǫgnvaldr supported Nicholas.

The identity of the half-brothers' shared father-in-law is uncertain. The chronicle describes him as a nobleman from Kintyre. This suggests he was a member of the Meic Somairle family, who were strongly linked to Kintyre. The father-in-law could have been Rǫgnvaldr's cousin Ragnall, or Ragnall's son Ruaidrí. Both were called "Lord of Kintyre." Or it could have been Ragnall's younger son, Domnall. The first marriage might have happened before 1210, possibly after 1200. This is because Rǫgnvaldr's son, Guðrøðr Dond, was an adult by 1223 and had a son by then.

These marriages were likely an attempt to improve relations between the Meic Somairle and the Crovan dynasty. These neighboring families had fought bitterly over the kingship of the Isles for about 60 years. Rǫgnvaldr's kingship might have been formally recognized by Ruaidrí, who seemed to be the main Meic Somairle leader after Áengus died in 1210. This would have made Ruaidrí a powerful lord within a unified Kingdom of the Isles. Since most of Ruaidrí's lands were on the mainland, the Scottish king likely saw this as a threat to his own claims over Argyll. The Scots might have released Óláfr in 1214 to cause family conflict in the Isles. If so, their plan failed temporarily because Óláfr made peace and married.

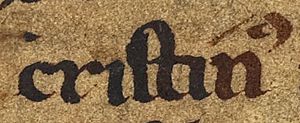

Civil War and Family Strife

Once Óláfr was free from his arranged marriage, the Chronicle of Mann says he married Cristina, daughter of Ferchar mac an tSacairt. Ferchar became known in 1215. By the mid-1220s, around the time of Cristina and Óláfr's marriage, Alexander II, King of Scotland rewarded Ferchar with the Earldom of Ross for his service. Óláfr's previous marriage to a Meic Somairle woman ended around the time Ruaidrí was seemingly driven from Kintyre by Alexander II's forces in 1221–1222. Óláfr's new alliance with Ferchar, Alexander's favorite, shows Óláfr recognized the shift in power in northwest Scotland. It might also signal Rǫgnvaldr's loss of Scottish support.

If the chronicle is true, Óláfr's separation from Lauon angered her sister. She secretly tricked her son, Guðrøðr Dond, into attacking Óláfr. Thinking he was following his father's orders, Guðrøðr Dond gathered an army on Skye. He went to Lewis and Harris and destroyed most of the island. Óláfr barely escaped with a few men and fled to his father-in-law in Ross. Óláfr was followed by Páll Bálkason, a sheriff on Skye who refused to fight Óláfr. The chronicle says they landed on Skye, found Guðrøðr Dond, and defeated him. His captured followers were killed, and Guðrøðr Dond himself was blinded.

Around this time, Joan, Queen of Scotland wrote to her brother, Henry III. She mentioned rumors that the Norwegian king was planning a naval expedition to the west. Joan's letter suggested this was a threat to English interests in Ireland. But it's more likely Hákon was focused on the growing conflict in the Isles. Óláfr might have asked Hákon for help against Rǫgnvaldr.

The family conflict mostly happened on Skye and Lewis and Harris. These islands were very important to the kingdom. Kings often gave northern territories to their heir-apparents or unhappy family members. For example, in the 1000s, the northern part of the kingdom might have been ruled by Guðrøðr Crovan's son, Lǫgmaðr. Rǫgnvaldr was in the Hebrides when his father died in 1187. This might mean Rǫgnvaldr was the rightful heir, despite the chronicle's claims. Also, Rǫgnvaldr's son was on Skye, suggesting he lived there as his father's heir. Rǫgnvaldr giving Lewis and Harris to Óláfr might mean Óláfr was seen as Rǫgnvaldr's rightful successor, at least for a while. Or it could have been a way to calm down an unhappy family member who was passed over for the kingship. Either way, this division of land would have greatly weakened the kingdom.

Church Disputes

The church area within Rǫgnvaldr's kingdom was the large Diocese of the Isles. Like the Kingdom of the Isles, this diocese might have started with the Uí Ímair's rule. In the mid-1100s, during Rǫgnvaldr's father's reign, the diocese became part of the new Norwegian Archdiocese of Niðaróss. The diocese's borders and its loyalty to Norway seemed to match the Kingdom of the Isles. But by the end of the 1100s, a new church area, the Diocese of Argyll, started to appear during the ongoing fights between the Meic Somairle and the Crovan dynasty.

In the early 1190s, the Chronicle of Mann says Cristinus, Bishop of the Isles, was removed. He was from Argyll and likely chosen by the Meic Somairle. He was replaced by Michael, a Manxman who Rǫgnvaldr probably supported. Cristinus had been bishop for at least 20 years during a time when the Meic Somairle were powerful. His downfall happened when the Crovan dynasty, led by the newly crowned Rǫgnvaldr, became strong again.

After Michael died in 1203, a man named Koli was consecrated in 1210. The situation during these years is unclear. The bishop's seat might have been empty. Or Koli might have been elected in 1203 but only consecrated later. Another possibility is that the area was managed from Lismore, the future seat of the Diocese of Argyll. This would have been under the authority of Áengus, the Meic Somairle leader killed in 1210.

Koli's consecration might also be linked to the attack on Iona in 1209/1210. The Norwegian expedition forced Rǫgnvaldr and his son to surrender to the Norwegian king in 1210. It also landed in Orkney and took the Orcadian earls and their bishop back to Norway. The whole operation might have been to reassert Norwegian control over both secular and church leaders in their overseas territories. If so, the trip seems to have been planned by Ingi and his chief bishop. Although the Meic Somairle controversially rebuilt Iona and put it under the Pope's protection, the Norwegian attack on the island might not have been planned. It's possible a visit by the Norwegian group turned violent by accident.

The next bishop after Koli was Reginald. Reginald's rival, Nicholas, had support from Furness and Rushen. But he never seemed to take the bishop's seat. Nicholas spent much time in Rome. Papal letters show he was exiled from his see because "the lord of the land and others" were "altogether opposed to him." As early as November 1219, the Pope urged the leaders of the Isles to accept Nicholas as bishop.

Rǫgnvaldr's good relations with the Pope and his worsening relationship with Óláfr suggest the papal letters supporting Nicholas were aimed at Óláfr, not Rǫgnvaldr. Rǫgnvaldr's support for Nicholas might also be shown by his renewal of St Mary's Abbey, Furness's right to elect the Bishop of the Isles. The English king's warning to Óláfr about harming the monks of Furness could mean Óláfr had a problem with them. Rǫgnvaldr's burial at Furness shows his own connection to the community. The dispute over bishops seems to be another part of the ongoing family conflict within the Crovan dynasty. Nicholas's final resignation in 1224 matches the kingdom's realignment between Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr. The whole dispute happened as Óláfr slowly gained power against Rǫgnvaldr. Reginald's successor was a man named John, who died in an accident. The next bishop was Simon, who was consecrated in 1226 and outlived both Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr.

Alliance with Alan of Galloway

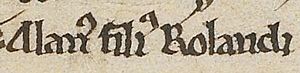

In 1224, the year after Rǫgnvaldr's son was defeated, the chronicle says Óláfr took hostages from the Hebridean leaders. With 32 ships, he landed on Mann at Ronaldsway. He confronted Rǫgnvaldr directly. They agreed to split the kingdom: Rǫgnvaldr kept Mann and the title of king, and Óláfr kept a share of the Hebrides. With Óláfr gaining power, Rǫgnvaldr turned to Alan, a powerful Scottish lord. Alan and Rǫgnvaldr were closely related. Both were great-grandsons of Fergus, Lord of Galloway. Both had received lands in Ulster from the English around the same time. Their connections might have led to Rǫgnvaldr's involvement with the Scottish king in Caithness.

In a letter to Henry III from 1224, Alan said he was busy with his army and fleet, traveling from island to island. This might show the start of joint military operations by Alan and Rǫgnvaldr against Óláfr, which the chronicle mentions for the next year. However, the chronicle says the campaign failed because the Manx people didn't want to fight Óláfr and the Hebrideans. Alan's letter suggests his actions in the Isles were related to his conflict with the Lacys in Ireland. This could mean the Lacys' ambitions in Ulster were aligned with Óláfr in the Isles.

Also in 1224, Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar reports that Hákon was visited by Gillikristr, Óttar Snækollsson, and many Islesmen. They brought letters about their lands' needs. These needs might refer to the violent family conflict and the recent treaty between the half-brothers. The saga might show that the Norwegian king was approached by either side of the conflict, or by neutral leaders caught in the middle. More attempts to stop the fighting through the Norwegian king might have happened in 1226, when Simon, Bishop of the Isles, met with Hákon.

A short time later, around 1225 or 1226, the chronicle says Rǫgnvaldr arranged for his daughter to marry Alan's young illegitimate son, Thomas. This marriage alliance cost Rǫgnvaldr his kingship. The chronicle records that the Manxmen removed him from power and replaced him with Óláfr. The resentment of this marriage suggests that Alan's son was meant to succeed Rǫgnvaldr. Rǫgnvaldr was about 60 years old, and his grandchildren were likely very young. Many Islesmen might have seen Óláfr as the rightful heir. This could explain why the Manxmen were not enthusiastic about Alan and Rǫgnvaldr's campaign in the Hebrides. Since Thomas was probably just a teenager, it would have been clear that Alan would hold the real power.

The Scottish king might have encouraged Alan's ambitions in the Isles. Alan's son could become a loyal king on Mann, extending Scottish power along the western coast and bringing stability. Alan himself faced the possibility that Galloway would be split among his legitimate daughters after his death. The marriage alliance might have been a way to secure a power base for Thomas, whose illegitimacy meant he couldn't inherit his father's lands under English and Scottish law.

At this low point, Rǫgnvaldr seems to have gone to Alan's court in Galloway. In 1228, while Óláfr and his leaders were away in the Hebrides, the chronicle reports an invasion of Mann by Rǫgnvaldr, Alan, and Thomas fitz Roland. The attack devastated the southern half of the island, almost turning it into a desert. The chronicle says Alan put bailiffs on Mann to collect tribute and send it to Galloway. This might show the price Rǫgnvaldr paid for Alan's help. Rǫgnvaldr's role in the takeover is not recorded.

Óláfr, facing serious setbacks, asked Henry III for English help against his half-brother. Henry III's letters to Óláfr mention aggression from Alan. Eventually, after Alan left Mann for home, Óláfr and his forces returned to the island. They defeated the remaining Gallovidians, and peace was restored to Mann.

That same year, English records show Henry III tried to make peace between the half-brothers. He gave Óláfr safe passage to England. This might explain Óláfr's temporary absence from Mann that year. It could also mark when Rǫgnvaldr finally lost English support. Although the English king officially recognized Óláfr's kingship the year before, the aggressive tone towards him suggests Rǫgnvaldr might have been the preferred ruler at that time.

Final Battle and Death

In early January 1229, the chronicle says Rǫgnvaldr surprised Óláfr's forces. Rǫgnvaldr sailed from Galloway with five ships and launched a night raid on the harbor at St Patrick's Isle, near Peel. During this attack, Rǫgnvaldr destroyed all of Óláfr's and his chieftains' ships. The chronicle's description hints at Galloway's involvement, as the expedition started there. But the fact that Rǫgnvaldr only had five ships suggests this support might have been weakening. This doesn't mean Alan abandoned Rǫgnvaldr, as Alan might have been fighting a rebellion against the Scottish king. Even so, Rǫgnvaldr might have seen Alan's involvement as a disadvantage at this point.

Rǫgnvaldr then established himself in the southern part of Mann. The chronicle says he gained the support of the southerners. Meanwhile, Óláfr gathered his forces in northern Mann. This means the island was divided between them for much of January and February, before their final confrontation. According to the chronicle, Rǫgnvaldr and Óláfr led their armies to Tynwald. The name "Tynwald" comes from Old Norse words meaning "assembly" and "field." This suggests that negotiations might have been planned there.

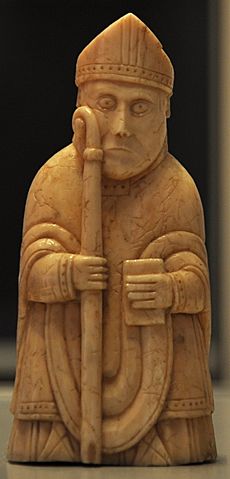

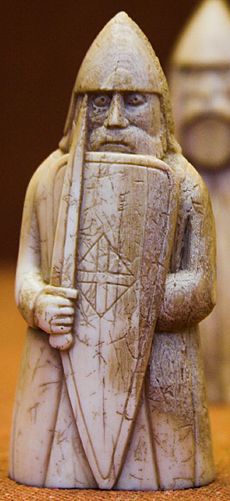

On 14 February, Óláfr's forces attacked Rǫgnvaldr at Tynwald. Rǫgnvaldr's troops were defeated, and he was killed. Icelandic records briefly confirm Rǫgnvaldr's death. Other sources suggest his death was due to betrayal. The Chronicle of Lanercost says Rǫgnvaldr "fell a victim to the arms of the wicked." The Chronicle of Mann says Óláfr grieved his half-brother's death but never sought revenge on his killers. The chronicle states that the monks of Rushen took Rǫgnvaldr's body to Furness, where he was buried at the abbey in a place he had chosen earlier. A stone statue of an armed warrior found at the abbey has been linked to Rǫgnvaldr since the 1800s, but this connection is uncertain.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |