Texas Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Texas Revolution |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

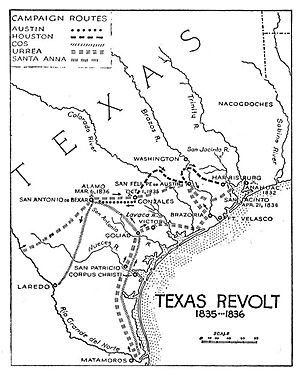

The campaigns of the Texas Revolution |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 2,000 | c. 6,500 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a fight where settlers from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) rebelled against the Mexican government. This happened in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. The Mexican government thought the United States had caused the uprising to take over Texas.

The revolution started in October 1835. This was after ten years of disagreements between the Mexican government and the growing number of American settlers in Texas. The Mexican government had become more powerful, and the rights of its citizens were limited. This was especially true for people moving from the United States. Mexico had also ended slavery in Texas in 1829. Many Anglo Texans wanted to keep slavery, which was a big reason for the conflict.

Settlers and Tejanos argued about their main goal. Some wanted complete independence, while others wanted to return to the Mexican Constitution of 1824. While leaders discussed their goals, Texians (Texas settlers) and many volunteers from the United States defeated small groups of Mexican soldiers by mid-December 1835. A new government was set up, but it struggled with disagreements.

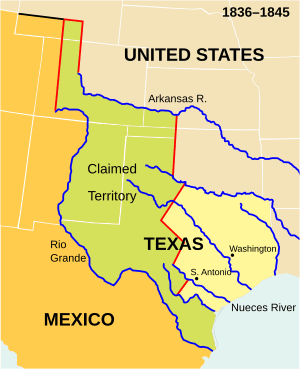

In March 1836, a second meeting declared Texas independent. They also chose leaders for the new Republic of Texas. Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna wanted to get Texas back. His army entered Texas in February 1836 and found the Texians unprepared. Mexican General José de Urrea led troops along the Texas coast. He defeated Texian forces and killed most of those who surrendered. Santa Anna led a larger force to San Antonio de Béxar. His troops won the Battle of the Alamo, killing almost all the defenders.

A new Texian army, led by Sam Houston, kept moving. Many scared civilians fled with the army in an event called the Runaway Scrape. On March 31, Houston stopped his men at Groce's Landing. For two weeks, the Texians trained hard. Santa Anna became too confident and divided his troops further. On April 21, Houston's army launched a surprise attack at the Battle of San Jacinto. The Mexican troops were quickly defeated. Texians killed many who tried to surrender. Santa Anna was captured. To save his life, he ordered the Mexican army to leave Texas. Mexico did not recognize the Republic of Texas. Small fights continued into the 1840s. Texas joined the United States in 1845. This led directly to the Mexican–American War.

Contents

Why the Revolution Started

After France tried to settle Texas in the late 1600s, Spain planned to settle the area. Texas shared a border with Louisiana to the east. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States also claimed land in Texas. From 1812 to 1813, people who opposed Spain and American adventurers rebelled. They declared Texas independent in 1813. However, the new Texas government and army were defeated in the Battle of Medina in August 1813. This was the deadliest battle in Texas history.

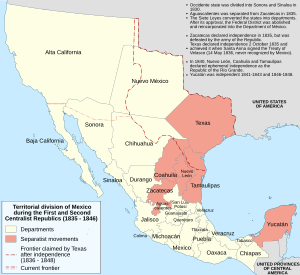

Texas became part of Mexico after the Mexican War of Independence. Under the Constitution of 1824, Texas and Coahuila became one state, Coahuila y Tejas. Texas had only one representative in the state government, which was far away. After many complaints from Tejanos (Mexican-born Texans), Texas became a separate part of the new state. Its capital was San Antonio de Béxar.

Texas had very few people, about 3,500 residents and 200 soldiers. This made it easy for native tribes and American adventurers to attack. To encourage more settlers and stop raids, Mexico allowed more people to move there. Soon, Anglo settlers from the United States greatly outnumbered the Tejanos. Many came from the southern United States and owned slaves. Most were Protestants and did not trust Catholics, which was Mexico's official religion.

Mexican leaders worried about the region's stability. In 1829, Mexico ended slavery, causing unrest. In response, President Anastasio Bustamante passed the Laws of April 6, 1830. These laws stopped more Americans from moving to Texas, increased taxes, and repeated the ban on slavery. Settlers often ignored these laws. By 1834, about 30,000 Anglos lived in Coahuila y Tejas, compared to only 7,800 Mexican-born residents. By late 1835, nearly 5,000 enslaved people lived in Texas.

In 1832, Antonio López de Santa Anna led a revolt to remove Bustamante. Texians, or English-speaking settlers, used this as a reason to fight. By mid-August, all Mexican troops had left east Texas. Texians held two meetings to ask Mexico to change the Laws of April 6, 1830. Bustamante was replaced by Valentin Gomez Farias, who tried to work with the Texans. In November 1833, Mexico addressed some concerns. They removed parts of the law and gave colonists more say in the government. Stephen F. Austin, who brought the first American settlers to Texas, wrote that "Every evil complained of has been remedied." Mexican leaders watched carefully, worried that the colonists wanted to break away.

Santa Anna removed Gomez Farias in April 1834. He soon showed he wanted a strong central government. In 1835, the 1824 Constitution was canceled. State governments were shut down, and local armies were disbanded. People who believed in a federal system across Mexico were upset. Citizens in Oaxaca and Zacatecas fought back. After Santa Anna's troops stopped the rebellion in Zacatecas in May, he allowed his soldiers to take things from the city for two days. Over 2,000 innocent people were killed.

Public opinion in Texas was divided. Some in the United States wanted Texas to be fully independent. After a small revolt against taxes in Anahuac in June, local leaders called for a meeting. They wanted to see if most settlers wanted independence, a return to federalism, or to keep things as they were. By late August, most communities agreed to send people to the Consultation on October 15.

By April 1835, military leaders in Texas asked for more soldiers. They feared the citizens would rebel. Mexico was not ready for a big civil war. But unrest in Texas was a danger to Santa Anna's power. If people in Coahuila also fought, Mexico could lose a lot of land. Without Texas as a buffer, American influence might spread. This could put Nuevo Mexico and Alta California at risk. Santa Anna wanted to stop the unrest before the United States got involved. In early September, Santa Anna ordered his brother-in-law, General Martín Perfecto de Cos, to lead 500 soldiers to Texas. Cos and his men arrived on September 20. Austin asked all towns to form local armies to defend themselves.

Texian Attacks: October–December 1835

The Gonzales Cannon Fight

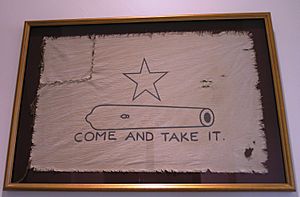

In the early 1830s, the Mexican army lent a small cannon to the people of Gonzales. This was for protection against Native American raids. On September 10, 1835, Mexican leaders decided it was not safe to leave the settlers with a weapon. Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea sent soldiers to get the cannon back. After settlers made the soldiers leave without the cannon, Ugartechea sent 100 soldiers with Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda. He ordered them to get the cannon, but to avoid fighting if possible.

Many settlers thought Mexico was looking for an excuse to attack. Texians delayed Castañeda for days, waiting for help from other towns. In the early morning of October 2, about 140 Texian volunteers attacked Castañeda's force. After a short fight, Castañeda asked to meet with Texian leader John Henry Moore. Castañeda said he agreed with their federalist ideas but had to follow orders. As Moore returned to camp, the Texians raised a homemade white flag. It had a black cannon painted on it with the words "Come and Take It". Castañeda realized he was outnumbered and left for Béxar. In this first battle, two Mexican soldiers were killed. Texians quickly claimed victory. News of the fight spread, encouraging many adventurers to join the fight in Texas.

More volunteers kept arriving in Gonzales. On October 11, the troops chose Austin as their leader. He had no military experience. Austin's first order was to remind his men to obey their officers. Encouraged by their win, the Texians decided to drive the Mexican army out of Texas. They began preparing to march to Béxar.

Gulf Coast Campaign

After hearing about the attack at Gonzales, Cos quickly went to Béxar. On October 6, Texians in Matagorda marched on Presidio La Bahía in Goliad. They wanted to capture Cos and take $50,000 rumored to be with him. On October 10, about 125 volunteers, including 30 Tejanos, stormed the fort. The Mexican soldiers surrendered after 30 minutes. One or two Texians were hurt, and three Mexican soldiers were killed.

The Texians stayed in the fort, led by Captain Philip Dimmitt. He sent all local Tejano volunteers to join Austin's march to Béxar. Later that month, Dimmitt sent men under Ira Westover to attack the Mexican fort at Fort Lipantitlán, near San Patricio. On November 3, the Texians took the fort without a fight. They then took apart the fort and prepared to return to Goliad. The rest of the Mexican soldiers, who had been on patrol, approached. They were with 15–20 loyal Mexicans from San Patricio. After a 30-minute fight, the Mexican soldiers and their allies left. With this win, the Texian army controlled the Gulf Coast. This forced Mexican commanders to send all messages by land, which was much slower.

When Westover's group returned to Goliad, they met Governor Viesca. He had been freed by friendly soldiers and came to Texas to restart the state government. Dimmitt welcomed Viesca but would not accept him as governor. This caused problems among the Texian soldiers. Dimmitt declared military rule and soon upset most local residents. Over the next few months, the area between Goliad and Refugio had civil unrest. A Goliad native, Carlos de la Garza, led small attacks against Texian troops.

Siege of Béxar

While Dimmitt was on the Gulf Coast, Austin led his men towards Béxar to fight Cos. Many delegates from the Consultation (the provisional government) joined the army. The Consultation was delayed until November 1. On October 16, the Texians stopped 25 miles (40 km) from Béxar. Austin sent a message to Cos, stating what the Texians needed to stop fighting. Cos replied that Mexico would not "yield to the dictates of foreigners".

About 650 Mexican soldiers quickly built defenses in the town. Within days, the Texian army, about 450 strong, began to surround Béxar. They slowly moved their camp closer. On October 27, a group led by James Bowie and James Fannin chose Mission Concepción as their next camp. They sent for the rest of the Texian army. When Ugartechea learned the Texians were divided, he led troops to attack Bowie and Fannin's men. The Mexican cavalry could not fight well in the wooded area. The Mexican infantry's weapons had a shorter range than the Texians'. After three Mexican attacks were pushed back, Ugartechea ordered a retreat. One Texian soldier died, and between 14 and 76 Mexican soldiers were killed.

As the weather got colder and food ran low, some Texians left without permission. Morale improved on November 18 when the first volunteers from the United States, the New Orleans Greys, joined the Texian army. Unlike most Texian volunteers, the Greys looked like soldiers. They had uniforms, good rifles, enough ammunition, and some discipline.

Austin left his command to become a representative to the United States. Soldiers then chose Edward Burleson as their new leader. On November 26, Burleson heard that a Mexican supply train of mules and horses, with 50–100 Mexican soldiers, was 5 miles (8 km) from Béxar. After some disagreement, Burleson sent Bowie and William H. Jack to stop the supplies. In the fight, Mexican forces had to retreat to Béxar, leaving their goods behind. To the Texians' disappointment, the bags only held food for the horses. This fight became known as the Grass Fight. This win briefly cheered the Texian troops, but morale dropped again as the weather got colder and men got bored.

After several plans to take Béxar by force were rejected by the Texian troops, Burleson suggested on December 4 that the army leave Béxar and go to Goliad until spring. In a final effort to avoid retreating, Colonel Ben Milam asked for volunteers to attack. The next morning, Milam and Colonel Frank W. Johnson led hundreds of Texians into the city. For the next four days, Texians fought house to house towards the fortified areas in the town center.

Cos received 650 more soldiers on December 8. But most were new recruits, many still in chains. They were not helpful and used up the limited food supplies. With few other choices, on December 9, Cos and most of his men went into the Alamo Mission outside Béxar. Cos planned a counterattack, but his cavalry officers refused, fearing they would be surrounded. About 175 soldiers from four cavalry groups left the mission and rode south. Mexican officers later said the men misunderstood their orders and were not deserting. The next morning, Cos surrendered.

Under the surrender terms, Cos and his men would leave Texas. They would no longer fight against those who supported the 1824 Constitution. With his departure, there were no organized Mexican troops in Texas. Many Texians believed the war was over. Burleson left his command on December 15 and went home. Many men did the same. Johnson took command of the 400 soldiers who remained.

Of the 1,300 men who volunteered for the Texian army in October and November 1835, only 150–200 came from the United States after October 2. The rest were Texans who had lived there for a while. However, after Cos surrendered, many Texans went home. Of the volunteers serving from January to March 1836, 78 percent had arrived from the United States after October 2, 1835.

Planning for the Future: November 1835 – February 1836

Texas Government and the Matamoros Plan

The Consultation finally met on November 3 in San Felipe. There were 58 of the 98 elected delegates. After days of strong debate, the delegates voted to create a temporary government. It would be based on the ideas of the 1824 Constitution. They did not declare independence. But they said they would not rejoin Mexico until the federal system was brought back. The new government would have a governor and a General Council. Each town would have one representative.

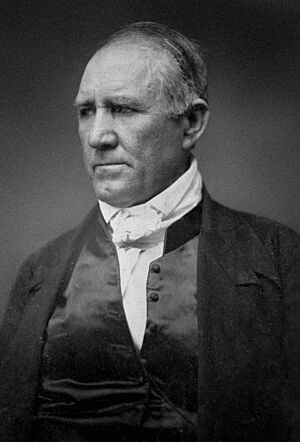

On November 13, delegates voted to create a regular army. They named Sam Houston its commander-in-chief. To attract volunteers from the United States, soldiers would get land. This was important because all public land belonged to the state or federal government. This showed that the delegates expected Texas to become independent. Houston had no power over the volunteer army led by Austin. Houston was also put on a committee for Native American affairs. Three men, including Austin, were asked to go to the United States. Their job was to get money, volunteers, and supplies. The delegates chose Henry Smith as governor. On November 14, the Consultation ended, leaving Smith and the Council in charge.

The new Texas government had no money. So, the military was allowed to take supplies. This policy soon made people dislike the council. Food and supplies became hard to find, especially near Goliad and Béxar, where Texian troops were. Few volunteers joined Houston's regular army. The Telegraph and Texas Register newspaper said that "some are not willing, under the present government, to do any duty... That our government is bad, all acknowledge."

Leaders in Texas kept debating if the army was fighting for independence or for the old federal system. On December 22, Texian soldiers at La Bahía declared independence. The Council did not want to decide this themselves. So, they called for another election for delegates to the Convention of 1836. The Council said all free white men could vote. Mexicans who did not support the central government could also vote. Smith tried to stop Mexicans from voting, even those who supported federalism.

Important federalists in Mexico, like former governor Viesca, Lorenzo de Zavala, and José Antonio Mexía, wanted to attack centralist troops in Matamoros. Council members liked the idea of a Matamoros Expedition. They hoped it would make other federalist states rebel. It would also keep bored Texian troops from leaving the army. Most importantly, it would move the war outside Texas. The Council approved the plan on December 25. On December 30, Johnson and his helper Dr. James Grant took most of the army and supplies to Goliad to get ready.

Arguments between Smith and the Council grew worse. On January 9, 1836, Smith threatened to fire the Council. He said they must cancel their approval of the Matamoros Expedition. Two days later, the Council voted to remove Smith. They named James W. Robinson as Acting Governor. It was unclear if either side had the power to remove the other. By this time, Texas was in chaos.

Under orders from Smith, Houston convinced all but 70 men not to follow Johnson. With his own power questioned, Houston left the army. He went to Nacogdoches to make a treaty with Cherokee leaders. Houston promised that Texas would recognize Cherokee land claims in East Texas. In return, the Cherokee would not attack settlements or help the Mexican army. In his absence, Fannin, the highest-ranking officer, led the men who did not want to go to Matamoros to Goliad.

The council did not give clear rules for the February vote for convention delegates. Each town decided how to balance the wishes of old residents and new volunteers from the United States. This caused confusion. In Nacogdoches, the election judge turned away 40 volunteers from Kentucky. The soldiers pulled out their weapons. Colonel Sidney Sherman said he "had come to Texas to fight for it." Eventually, the troops were allowed to vote. With rumors that Santa Anna was preparing a large army, the conflict became seen as a race war.

Mexico's Army of Operations

News of the fighting at Gonzales reached Santa Anna on October 23. Few people in Mexico, besides the leaders and army, knew or cared about the revolt. Those who knew blamed the Anglos for not following Mexican laws and culture. They felt Anglo immigrants had forced a war on Mexico. Mexican honor demanded that the rebels be defeated. Santa Anna gave his presidential duties to Miguel Barragán. He wanted to personally lead troops to end the Texian revolt. Santa Anna and his soldiers believed the Texians would be easily scared. The Mexican Secretary of War, José María Tornel, wrote that Mexican soldiers were better than "mountaineers of Kentucky and the hunters of Missouri."

At this time, Mexico had only 2,500 soldiers. This was not enough to stop a rebellion and protect against Native American and federalist attacks. Santa Anna got three loans to pay for the Texas expedition. He began to gather a new army, called the Army of Operations in Texas. Most of the soldiers were forced into service or were people who had broken laws and chose military service over jail. Mexican officers knew their muskets had a shorter range than Texian weapons. But Santa Anna believed his plans would lead to an easy win. There was a lot of corruption, and supplies were scarce. From the start, food was short, and there were no medical supplies or doctors. Few troops had warm coats or blankets for winter.

In late December, Santa Anna had the Mexican Congress pass the Tornel Decree. This law said that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates." In the early 1800s, captured pirates were immediately killed. This meant the Mexican army could kill Texian fighters without taking prisoners. This information was not widely known. Most American recruits in the Texian army probably did not know they would not be taken as prisoners of war.

By December 1835, 6,019 soldiers began their march to Texas. Progress was slow. There were not enough mules to carry all the supplies. Many civilian wagon drivers quit when their pay was delayed. Many women and children followed the army, which further reduced the already scarce supplies. In Saltillo, Cos and his men from Béxar joined Santa Anna's forces. Santa Anna ignored Cos's promise not to fight in Texas, saying it was made to rebels.

From Saltillo, the army had three ways to go. Santa Anna ordered General José de Urrea to lead 550 troops to Goliad. Some of Santa Anna's officers wanted the whole army to go along the coast. This way, supplies could come by sea. But Santa Anna focused on Béxar, the political center of Texas. It was also where Cos had been defeated. Santa Anna wanted to restore his family's and Mexico's honor. Santa Anna might also have thought Béxar would be easier to defeat. His spies told him most of the Texian army was along the coast, preparing for the Matamoros Expedition. Santa Anna led most of his men up the Camino Real to approach Béxar from the west. This surprised the Texians, who expected an attack from the south. On February 17, they crossed the Nueces River, officially entering Texas.

Temperatures dropped very low. By February 13, about 15–16 inches (38–41 cm) of snow had fallen. Many new soldiers were from the warm climate of the Yucatán. They could not get used to the harsh winter. Some died from cold, and others got sick. Soldiers who fell behind were sometimes killed by Comanche raiding parties. Still, the army kept marching towards Béxar. As they moved, settlers in their path in South Texas left their homes and went north. The Mexican army searched and sometimes burned the empty homes. Santa Anna and his commanders got good information about Texian troop locations and plans. This came from a network of Tejano spies organized by de la Garza.

Santa Anna's Attacks: February–March 1836

The Alamo Battle

Fewer than 100 Texian soldiers remained at the Alamo Mission in Béxar. They were led by Colonel James C. Neill. He could not spare enough men to defend the large fort. In January, Houston sent Bowie with 30 men to remove the cannons and destroy the complex. Bowie wrote to Governor Smith that "the salvation of Texas depends in great measure on keeping Béxar out of the hands of the enemy." He added, "Colonel Neill and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy." Few extra soldiers were sent. Cavalry officer William B. Travis arrived in Béxar with 30 men on February 3. Five days later, a small group of volunteers arrived, including the famous frontiersman Davy Crockett. On February 11, Neill left to get more soldiers and supplies. In his absence, Travis and Bowie shared command.

On February 23, scouts reported that the Mexican army was in sight. The unprepared Texians gathered what food they could find in town. They then went back to the Alamo. By late afternoon, about 1,500 Mexican troops occupied Béxar. They quickly raised a blood-red flag, meaning they would take no prisoners. For the next 13 days, the Mexican army surrounded the Alamo. Several small fights gave the defenders hope, but did not change much. Bowie became ill on February 24, leaving Travis in sole command. That same day, Travis sent messengers with a letter To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World. He begged for more soldiers and promised "victory or death." This letter was printed in the United States and Europe. Texian and American volunteers gathered in Gonzales, waiting for Fannin to lead them to help the Alamo. After days of not deciding, Fannin prepared to march his 300 troops to the Alamo on February 26. But they turned back the next day. Fewer than 100 Texian reinforcements reached the fort.

About 1,000 more Mexican soldiers arrived on March 3. The next day, a local woman, likely Bowie's relative Juana Navarro Alsbury, tried to arrange a surrender for the Alamo defenders. Santa Anna refused. This visit made Santa Anna more impatient. He planned an attack for early March 6. Many of his officers were against the plan. They wanted to wait until the cannons had damaged the Alamo's walls more, forcing the defenders to surrender. Santa Anna believed a clear victory would boost morale and send a strong message to others fighting in Texas.

In the early hours of March 6, the Mexican army attacked the fort. Troops from Béxar were kept from the front lines. This was so they would not have to fight their families and friends. At first, the Mexican troops were at a disadvantage. Their column formation meant only the front rows could fire safely. But inexperienced new soldiers in the back also fired their weapons. Many Mexican soldiers were accidentally killed. As Mexican soldiers climbed over the walls, at least 80 Texians fled the Alamo. They were cut down by Mexican cavalry. Within an hour, almost all of the Texian defenders, estimated at 182–257 men, were killed. Between four and seven Texians, possibly including Crockett, surrendered. General Manuel Fernández Castrillón tried to save them, but Santa Anna insisted they be killed immediately.

Most historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. This was about one-third of the Mexican soldiers in the final attack. This is a very high number of casualties. The battle was not important militarily, but it had a huge political impact. Travis had bought time for the Convention of 1836, planned for March 1, to meet. If Santa Anna had not stopped in Béxar for two weeks, he would have reached San Felipe by March 2. He likely would have captured the delegates or made them flee.

The survivors, mostly women and children, were questioned by Santa Anna and then released. Susanna Dickinson was sent with Travis's slave Joe to Gonzales. She was to spread the news of the Texian defeat. Santa Anna thought that knowing the large number of Mexican troops and the fate of the Alamo soldiers would stop the resistance. He believed Texian soldiers would quickly leave.

Goliad Campaign

Urrea reached Matamoros on January 31. He was a federalist himself. He soon convinced other federalists that the Texians' real goal was to break away from Mexico. He said their plan to start a federalist revolt in Matamoros was just a way to distract from themselves. Mexican double agents kept telling Johnson and Grant that they could easily take Matamoros. While Johnson waited in San Patricio with a small group, Grant and between 26 and 53 others explored the area. They were supposedly looking for more horses. But Grant was likely also trying to contact his sources in Matamoros to plan an attack.

Just after midnight on February 27, Urrea's men surprised Johnson's forces. Six Texians, including Johnson, escaped. The rest were captured or killed. After learning where Grant was from local spies, Mexican soldiers ambushed the Texians at Agua Dulce Creek on March 2. Twelve Texians were killed, including Grant. Four were captured, and six escaped. Urrea's orders were to kill those captured. But he sent them to Matamoros as prisoners instead.

On March 11, Fannin sent Captain Amon B. King to help people leave the mission in Refugio. King and his men spent a day searching local ranches for people who supported the central government. They returned to the mission on March 12. Soon, Urrea's advance troops and de la Garza's soldiers surrounded them. That same day, Fannin received orders from Houston to destroy Presidio La Bahía (now called Fort Defiance) and march to Victoria. Fannin did not want to leave any of his men behind. So, he sent William Ward with 120 men to help King's company. Ward's men drove off the troops surrounding the church. But instead of returning to Goliad, they stayed a day longer to raid more ranches.

Urrea arrived with almost 1,000 troops on March 14. At the battle of Refugio, similar to the battle of Concepción, the Texians pushed back several attacks. They caused many casualties, using their more accurate rifles. By the end of the day, the Texians were hungry, thirsty, tired, and almost out of ammunition. Ward ordered a retreat. Under the cover of darkness and rain, the Texian soldiers slipped through Mexican lines. They left several badly wounded men behind. Over the next few days, Urrea's men, with help from local centralist supporters, rounded up many Texians who had escaped. Most were killed. However, Urrea pardoned a few after their wives begged for their lives. Mexican Colonel Juan José Holzinger insisted that all non-Americans be spared.

By the end of March 16, most of Urrea's forces marched to Goliad to trap Fannin. Still waiting for news from King and Ward, Fannin kept delaying his departure from Goliad. As they prepared to leave on March 18, Urrea's advance troops arrived. For the rest of the day, the two groups of cavalry fought without much purpose. This only tired the Texian oxen, which had been tied to their wagons all day without food or water.

The Texians began their retreat on March 19. The pace was slow. After traveling only 4 miles (6.4 km), the group stopped for an hour to rest and let the oxen eat. Urrea's troops caught up to the Texians later that afternoon. Fannin and his force of about 300 men were crossing a prairie. Urrea had learned from the fighting at Refugio. He was determined that the Texians would not reach the trees about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) ahead, along Coleto Creek. As Mexican forces surrounded them, the Texians formed a tight square for defense. They pushed back three attacks during this battle of Coleto. About nine Texians were killed and 51 wounded, including Fannin. Urrea lost 50 men, with another 140 wounded. Texians had little food, no water, and running low on ammunition. But they voted not to try to break for the trees, as they would have had to leave the wounded behind.

The next morning, March 20, Urrea showed off his men and his newly arrived cannons. Seeing their hopeless situation, the Texians with Fannin surrendered. Mexican records show that the Texians surrendered without conditions. Texian accounts claim that Urrea promised the Texians would be treated as prisoners of war and sent to the United States. Two days later, a group of Urrea's men surrounded Ward and the last of his group less than 1 mile (1.6 km) from Victoria. Despite Ward's strong objections, his men voted to surrender. They later said they were told they would be sent back to the United States.

On Palm Sunday, March 27, Fannin, Ward, Westover, and their men were marched out of the fort and shot. Mexican cavalry were nearby to catch anyone who tried to escape. About 342 Texians died. 27 either escaped or were saved by Mexican troops. Several weeks after the Goliad massacre, the Mexican Congress officially pardoned any Texas prisoners who had been sentenced to death.

Texas Convention of 1836

The Convention of 1836 in Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1 had 45 delegates. They represented 21 towns. Within an hour of the convention starting, George C. Childress presented a proposed Texas Declaration of Independence. It passed by a large vote on March 2. On March 6, hours after the Alamo had fallen, Travis's last message arrived. His distress was clear. Delegate Robert Potter immediately suggested that the convention stop and all delegates join the army. Houston convinced the delegates to stay. He then left to take charge of the army. With the convention's support, Houston was now the commander-in-chief of all Texas forces.

Over the next ten days, delegates wrote a constitution for the Republic of Texas. Parts of the document were copied directly from the United States Constitution. Other parts were rephrased. The new nation's government was similar to the United States'. It had two legislative bodies, a chief executive, and a supreme court. Unlike its model, the new constitution allowed taking goods and forcing soldiers to stay in homes. It also clearly made slavery legal. After adopting the constitution on March 17, delegates chose temporary leaders to govern the country. Then they ended the meeting. David G. Burnet, who was not a delegate, was elected president. The next day, Burnet announced the government was moving to Harrisburg.

The Retreat: March–May 1836

Texian Retreat: The Runaway Scrape

On March 11, Santa Anna sent one group of troops to join Urrea. Their orders were to move to Brazoria once Fannin's men were defeated. A second group of 700 troops under General Antonio Gaona would go along the Camino Real to Mina, and then to Nacogdoches. General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma would take another 700 men to San Felipe. The Mexican groups were moving northeast on paths roughly parallel, about 40–50 miles (64–80 km) apart.

The same day Mexican troops left Béxar, Houston arrived in Gonzales. He told the 374 volunteers there that Texas was now an independent republic. Just after 11 p.m. on March 13, Susanna Dickinson and Joe brought news that the Alamo had fallen. They said the Mexican army was marching towards Texian settlements. A quick meeting decided to leave the area and retreat. The evacuation started at midnight. It happened so fast that many Texian scouts did not know the army had moved. Everything that could not be carried was burned. The army's only two cannons were thrown into the Guadalupe River. When Ramírez y Sesma reached Gonzales on the morning of March 14, he found the buildings still smoking.

Most people fled on foot, many carrying their small children. A cavalry group led by Seguín and Salvador Flores was assigned to protect the rear. Their job was to evacuate isolated ranches and protect civilians from Mexican troops or Native Americans. The further the army retreated, the more civilians joined the flight. For both armies and the civilians, the pace was slow. Heavy rains had flooded the rivers and turned the roads into mud.

As news of the Alamo's fall spread, the number of volunteers grew. By March 19, there were about 1,400 men. Houston learned of Fannin's defeat on March 20. He realized his army was the last hope for an independent Texas. Houston worried that his untrained army would only be good for one battle. He also knew Urrea's forces could easily outflank his men. So, Houston kept avoiding a fight, which greatly displeased his troops. By March 28, the Texian army had retreated 120 miles (190 km) across the Navidad and Colorado Rivers. Many troops left. Those who stayed complained that their commander was a coward.

On March 31, Houston stopped his men at Groce's Landing, about 15 miles (24 km) north of San Felipe. Two companies that refused to retreat further were assigned to guard the Brazos River crossings. For the next two weeks, the Texians rested and recovered from illness. For the first time, they began practicing military drills. While there, two cannons, called the Twin Sisters, arrived from Cincinnati, Ohio. Interim Secretary of War Thomas Rusk joined the camp. He had orders from Burnet to replace Houston if he refused to fight. Houston quickly convinced Rusk that his plans were good. Secretary of State Samuel P. Carson advised Houston to keep retreating to the Sabine River. There, more volunteers would likely come from the United States, allowing the army to counterattack. Burnet was unhappy with everyone. He wrote to Houston: "The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight." Complaints in the camp became so strong that Houston posted notices. They said anyone trying to take his place would be court-martialed and shot.

Santa Anna and a smaller force had stayed in Béxar. After hearing that the acting president, Miguel Barragán, had died, Santa Anna thought about returning to Mexico City. He wanted to strengthen his power. But fear that Urrea's victories would make him a political rival convinced Santa Anna to stay in Texas. He wanted to personally oversee the final part of the campaign. He left on March 29 to join Ramírez y Sesma. He left only a small force to hold Béxar. At dawn on April 7, their combined force marched into San Felipe. They captured a Texian soldier who told Santa Anna that the Texians planned to retreat further if the Mexican army crossed the Brazos River. Santa Anna could not cross the Brazos because of the small group of Texians blocking the crossing. On April 14, a frustrated Santa Anna led about 700 troops to capture the temporary Texas government. Government officials fled just hours before Mexican troops arrived in Harrisburg. Santa Anna sent Colonel Juan Almonte with 50 cavalry to stop them in New Washington. Almonte arrived just as Burnet left in a rowboat, heading for Galveston Island. Although the boat was still within range of their weapons, Almonte ordered his men not to fire. He did not want to endanger Burnet's family.

At this point, Santa Anna believed the rebellion was almost over. The Texian government had been forced off the mainland. They had no way to talk to their army, which had shown no interest in fighting. He decided to block the Texian army's retreat and end the war. Almonte's scouts wrongly reported that Houston's army was going to Lynchburg Crossing. This was on Buffalo Bayou, to join the government in Galveston. So Santa Anna ordered Harrisburg burned and went on towards Lynchburg.

The Texian army had continued their march eastward. On April 16, they came to a crossroads. One road led north towards Nacogdoches, the other to Harrisburg. Without orders from Houston and no discussion among themselves, the leading troops took the road to Harrisburg. They arrived on April 18, not long after the Mexican army had left. That same day, Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes captured a Mexican messenger. He was carrying information about the locations and future plans of all Mexican troops in Texas. Realizing that Santa Anna had only a small force and was nearby, Houston gave a powerful speech to his men. He urged them to "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad." His army then rushed towards Lynchburg. Houston worried that his men might not tell the difference between Mexican soldiers and the Tejanos in Seguín's company. So, he first ordered Seguín and his men to stay in Harrisburg. They were to guard those too sick to travel quickly. After strong protests from Seguín and Antonio Menchaca, the order was canceled. But the Tejanos had to wear a piece of cardboard in their hats to show they were Texian soldiers.

San Jacinto Battle

The area along Buffalo Bayou had many thick oak trees and marshes. This type of land was familiar to the Texians but very strange to the Mexican soldiers. Houston's army, with 900 men, reached Lynch's Ferry in the morning on April 20. Santa Anna's 700-man force arrived a few hours later. The Texians camped in a wooded area along the bayou. This spot provided good cover and helped hide their full strength. But it also left the Texians no room to retreat. Despite protests from several of his officers, Santa Anna chose to camp in a weak spot. It was a plain near the San Jacinto River, bordered by woods on one side and marsh and lake on another. The two camps were about 500 yards (460 m) apart. They were separated by a grassy area with a small hill in the middle. Colonel Pedro Delgado later wrote that Santa Anna's chosen camp was "against military rules."

Over the next few hours, two short fights happened. Texians won the first, forcing a small group of Mexican cavalry and artillery to leave. Mexican cavalry then forced the Texian cavalry to retreat. In the confusion, Rusk, who was on foot to reload his rifle, was almost captured by Mexican soldiers. But he was saved by a newly arrived Texian volunteer, Mirabeau B. Lamar. Despite Houston's objections, many infantrymen rushed onto the field. As the Texian cavalry fell back, Lamar stayed behind to save another Texian who had been thrown from his horse. Mexican officers reportedly praised his bravery. Houston was angry that the infantry had disobeyed his orders. This gave Santa Anna a better idea of their strength. The men were equally upset that Houston had not allowed a full battle.

Throughout the night, Mexican troops worked to strengthen their camp. They built defenses from anything they could find, including saddles and brush. At 9 a.m. on April 21, Cos arrived with 540 more soldiers. This brought the Mexican force to 1,200 men, outnumbering the Texians. Cos's men were new recruits, not experienced soldiers. They had marched steadily for more than 24 hours, with no rest or food. As the morning passed with no Texian attack, Mexican officers relaxed. By afternoon, Santa Anna had given permission for Cos's men to sleep. His own tired troops also rested, ate, and bathed.

Not long after the Mexican reinforcements arrived, Houston ordered Smith to destroy Vince's Bridge, 5 miles (8 km) away. This was to slow down any more Mexican reinforcements. At 4 p.m., the Texians began creeping quietly through the tall grass, pulling the cannons behind them. The Texian cannon fired at 4:30, starting the battle of San Jacinto. After a single volley, Texians broke ranks. They swarmed over the Mexican defenses to fight hand-to-hand. Mexican soldiers were completely surprised. Santa Anna, Castrillón, and Almonte shouted often conflicting orders, trying to organize their men. Within 18 minutes, Mexican soldiers left their camp and ran for their lives.

Many Mexican soldiers retreated through the marsh to Peggy Lake. Texian riflemen stood on the banks and shot at anything that moved. Many Texian officers, including Houston and Rusk, tried to stop the killing. But they could not control the men. Texians kept chanting "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!" while scared Mexican infantry yelled "Me no Alamo!" and begged for mercy. In what one historian called "one of the most one-sided victories in history," 650 Mexican soldiers were killed and 300 captured. Eleven Texians died, with 30 others, including Houston, wounded.

Santa Anna's troops had been completely defeated. But they were not the main part of the Mexican army in Texas. Another 4,000 troops remained under Urrea and General Vicente Filisola. Texians had won the battle because of Santa Anna's mistakes. Houston knew his troops would have little hope of winning again against Urrea or Filisola. As darkness fell, a large group of prisoners was led into camp. Houston first thought they were Mexican reinforcements and shouted that all was lost.

Mexican Retreat and Surrender

Santa Anna had escaped towards Vince's Bridge. Finding the bridge destroyed, he hid in the marsh and was captured the next day. He was brought before Houston, who had been shot in the ankle and badly wounded. Texian soldiers gathered around, demanding the Mexican general be killed immediately. To save his life, Santa Anna suggested he order the remaining Mexican troops to stay away. In a letter to Filisola, who was now the highest-ranking Mexican official in Texas, Santa Anna wrote that "yesterday evening [we] had an unfortunate encounter" and ordered his troops to retreat to Béxar and wait for more instructions.

Urrea urged Filisola to continue the fight. He was confident he could defeat the Texian troops. However, Filisola did not want to risk another defeat. Spring rains ruined the ammunition and made the roads almost impossible to use. Troops sank to their knees in mud. Mexican troops soon ran out of food and began to get sick. Their supply lines had completely broken down, so there was no hope of more soldiers. Filisola later wrote that if the enemy had met them in these conditions, they would have had to die or surrender.

For several weeks after San Jacinto, Santa Anna continued to talk with Houston, Rusk, and then Burnet. Santa Anna suggested two treaties. One was public, with promises made between the two countries. The other was private, with Santa Anna's personal agreements. The Treaties of Velasco required all Mexican troops to retreat south of the Rio Grande. It also said that all private property (meaning slaves) should be respected and returned. Prisoners of war would be released unharmed. Santa Anna would be given passage to Veracruz immediately. He secretly promised to convince the Mexican Congress to recognize the Republic of Texas. He also promised to recognize the Rio Grande as the border.

When Urrea began marching south in mid-May, many families from San Patricio who had supported the Mexican army went with him. When Texian troops arrived in early June, they found only 20 families left. The area around San Patricio and Refugio saw a "noticeable decrease in population" during the Republic of Texas years. Although the treaty said Urrea and Filisola would return any slaves their armies had protected, Urrea refused. Many former slaves followed the army to Mexico, where they could be free. By late May, the Mexican troops had crossed the Nueces. Filisola fully expected that the defeat was temporary. He thought a second campaign would be launched to retake Texas.

What Happened Next

Military Outcomes

When Mexican leaders heard about Santa Anna's defeat at San Jacinto, flags across the country were lowered in mourning. Mexican leaders said any agreements signed by Santa Anna, a prisoner of war, were not valid. They refused to recognize the Republic of Texas. Filisola was criticized for leading the retreat and was quickly replaced by Urrea. Within months, Urrea gathered 6,000 troops in Matamoros, ready to retake Texas. However, the new Mexican invasion of Texas never happened. Urrea's army was sent to deal with other rebellions in Mexico.

Most people in Texas thought the Mexican army would return quickly. So many American volunteers came to the Texian army after the victory at San Jacinto that the Texian government could not keep an accurate list of enlistments. As a precaution, Béxar remained under military rule throughout 1836. Rusk ordered all Tejanos in the area between the Guadalupe and Nueces Rivers to move to east Texas or Mexico. Some who refused were forced to leave. New Anglo settlers moved in and used threats and legal tricks to take land once owned by Tejanos. Over the next few years, hundreds of Tejano families moved to Mexico.

For years, Mexican leaders used the idea of retaking Texas to justify new taxes. They also made the army the top spending priority for the poor nation. Only small fights happened. Larger expeditions were delayed because military money was always sent to other rebellions. This was due to fear that those regions would join Texas and break up the country even more. The northern Mexican states briefly formed an independent Republic of the Rio Grande in 1839. In the same year, the Mexican Congress thought about a law to make it treason to speak positively about Texas. In June 1843, leaders of the two nations agreed to a ceasefire.

Republic of Texas

On June 1, 1836, Santa Anna boarded a ship to go back to Mexico. For the next two days, crowds of Texian soldiers, many who had just arrived from the United States, demanded he be killed. Lamar, now Secretary of War, gave a speech saying that "Mobs must not intimidate the government." But on June 4, soldiers seized Santa Anna and put him under military arrest. This event greatly weakened the temporary government. A group of soldiers tried an unsuccessful takeover in mid-July. In response, Burnet called for elections to approve the constitution and elect a Congress. This was the sixth group of leaders for Texas in 12 months. Voters overwhelmingly chose Houston as the first president. They approved the constitution from the Convention of 1836. They also approved a request to join the United States. Houston ordered Santa Anna to Washington, D.C., and from there he was soon sent home.

During his absence, Santa Anna had been removed from power. When he arrived, the Mexican press immediately attacked him for his cruelty towards the prisoners killed at Goliad. In May 1837, Santa Anna asked for an investigation into the event. The judge said the investigation was only to find facts and took no action. Press attacks in both Mexico and the United States continued. Santa Anna was disgraced until the next year, when he became a hero in the Pastry War.

The first Texas Legislature refused to approve the treaty Houston had signed with the Cherokee. They said he had no authority to make any promises. The temporary Texian governments had promised to pay citizens for goods taken during the war. But most livestock and horses were not returned. Veterans were promised land. In 1879, surviving Texian veterans who served more than three months from October 1, 1835, to January 1, 1837, were given an extra 1,280 acres (518 ha) of public land. Over 1.3 million acres (526 thousand ha) of land were given out. Some of this was in Greer County, which was later found to be part of Oklahoma.

Republic of Texas laws changed the status of many people living in the region. The constitution did not allow free black people to live in Texas permanently. Individual slaves could only be freed by a special order from Congress. The newly freed person would then be forced to leave Texas. Women also lost important legal rights under the new constitution. It replaced the Spanish law system with English common law. Under common law, the idea of community property was removed. Women could no longer act for themselves legally, like signing contracts, owning property, or suing. Some of these rights were given back in 1845 when Texas added them to the new state constitution. During the Republic of Texas years, Tejanos also faced much unfair treatment.

Foreign Relations

Mexican leaders blamed the loss of Texas on the United States. The United States officially stayed neutral. But 40 percent of the men who joined the Texian army from October 1 to April 21 came from the United States after the fighting began. More than 200 of the volunteers were members of the United States Army. None were punished when they returned to their posts. American individuals also gave supplies and money to help Texas become independent. For the next ten years, Mexican politicians often criticized the United States for its citizens' involvement.

The United States agreed to recognize the Republic of Texas in March 1837. But it refused to take Texas as a state. The new republic then tried to convince European nations to recognize it. In late 1839, France recognized the Republic of Texas. They were convinced it would be a good trading partner.

For several decades, official British policy was to keep strong ties with Mexico. They hoped Mexico could stop the United States from expanding further. When the Texas Revolution started, Great Britain did not get involved. They officially said they were confident Mexico could handle its own affairs. In 1840, after years where the Republic of Texas was neither joined by the United States nor taken back by Mexico, Britain signed a treaty. It recognized Texas and agreed to help Texas get recognition from Mexico.

The United States voted to annex Texas as the 28th state in March 1845. Two months later, Mexico agreed to recognize the Republic of Texas. This was only if Texas did not join the United States. On July 4, 1845, Texans voted to join the United States. This led to the Mexican–American War. In this war, Mexico lost almost 55 percent of its land to the United States. It also formally gave up its claim on Texas.

Legacy of the Revolution

No new fighting techniques were used during the Texas Revolution. But the number of deaths and injuries was very unusual for the time. Usually, in 1800s warfare, the number of wounded was two or three times higher than those killed. From October 1835 to April 1836, about 1,000 Mexican and 700 Texian soldiers died. The wounded numbered 500 Mexican and 100 Texian. This difference was because Santa Anna decided to call Texian rebels traitors. It was also because Texians wanted revenge.

During the revolution, Texian soldiers became known for their bravery and fighting spirit. Less than five percent of the Texian population joined the army during the war. Texian soldiers knew the Mexican cavalry was much better than their own. Over the next ten years, the Texas Rangers copied Mexican cavalry tactics. They adopted the Spanish saddle and spurs, the riata (lasso), and the bandana.

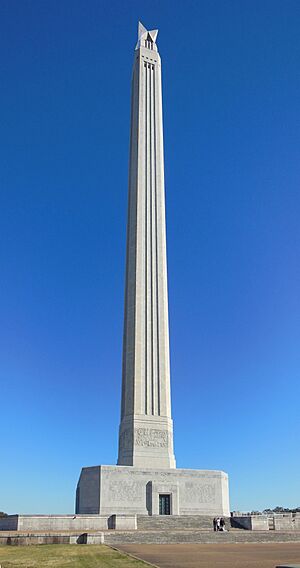

The Texas Veterans Association, made up only of revolutionary veterans living in Texas, was active from 1873 to 1901. It helped convince the government to create a monument to honor the San Jacinto veterans. In the late 1800s, the Texas government bought the San Jacinto battlefield. It is now home to the San Jacinto Monument, the tallest stone monument in the world. In the early 1900s, the Texas government bought the Alamo Mission. It is now an official state shrine. In front of the church, in the center of Alamo Plaza, stands a cenotaph. It is a monument that honors the defenders who died during the battle. More than 2.5 million people visit the Alamo every year.

The Texas Revolution has been written about in poems and many books, plays, and films.

Images for kids

-

The Fall of the Alamo depicts Davy Crockett swinging his rifle at Mexican troops who have breached the south gate of the mission.

-

Presidio La Bahía, also known as Fort Defiance, in Goliad

-

"Surrender of Santa Anna" by William Henry Huddle shows the Mexican president and general surrendering to a wounded Sam Houston, battle of San Jacinto

See also

In Spanish: Independencia de Texas para niños

In Spanish: Independencia de Texas para niños