Common thresher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Common thresher |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Alopiidae |

| Genus: | Alopias |

| Species: |

A. vulpinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Alopias vulpinus (Bonnaterre, 1788)

|

|

|

|

| Confirmed (dark blue) and suspected (light blue) range of the common thresher | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

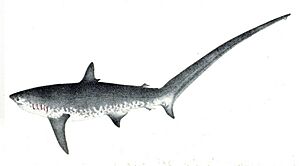

The common thresher (Alopias vulpinus), also called the Atlantic thresher, is the biggest type of thresher shark. It can grow up to 6 meters (20 feet) long. About half of its length is its super long tail fin. This shark has a sleek body, a short pointed snout, and medium-sized eyes. It looks a lot like the pelagic thresher shark.

You can tell the common thresher apart by the white color on its belly. This white color goes up in a band over the bases of its pectoral fins (the fins on its sides). Common threshers live all over the world in both warm and cool waters. They prefer cooler temperatures. You can find them near the shore or far out in the open ocean. They swim from the surface down to about 550 meters (1,800 feet) deep. These sharks travel to different places depending on the season. They spend summers in warmer areas.

The common thresher's long tail is used like a whip. It helps them hit and stun their prey. These sharks mostly eat small schooling fish like herrings and anchovies. They are fast, strong swimmers and can even jump out of the water! They have special body features that keep them warmer than the surrounding ocean water. Common threshers give birth to live young. Their babies grow by eating undeveloped eggs inside their mother. Females usually have four pups at a time after being pregnant for nine months.

Even though they are big, common threshers are not very dangerous to humans. They have small teeth and are usually shy. People value this shark for its meat, fins, skin, and liver oil. Many are caught by large fishing boats using longlines and gillnets. Sport fishers also like to catch them because they put up a great fight. Common threshers do not have many babies, so they cannot handle too much fishing. For example, the thresher shark fishing industry off California quickly collapsed in the 1980s. Because more and more common threshers are being caught, the International Union for Conservation of Nature says this species is vulnerable.

Contents

Discovering the Common Thresher

The common thresher shark was first described by a French scientist named Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre. He named it Squalus vulpinus in 1788. Later, another scientist named Constantine Samuel Rafinesque described a similar shark as Alopias macrourus in 1810. Scientists then realized that Alopias was a good name for this type of shark. They also found that A. macrourus was the same as S. vulpinus. So, the shark's official scientific name became Alopias vulpinus.

The word vulpinus comes from the Latin word vulpes, which means "fox". This is why the common thresher was first called the "fox shark" in English. People in ancient times thought these sharks were very clever, like foxes. In the mid-1800s, the name "thresher" became more popular. This name refers to how the shark uses its tail like a flail, or "thresher," to hit prey. Scientists Henry Bigelow and William Schroeder gave it the name "common thresher" in 1945. This helped tell it apart from other thresher sharks. It also has many other names like sea fox, slasher, and whiptail shark.

What Does a Common Thresher Look Like?

The common thresher is a strong shark with a body shaped like a torpedo. It has a short, wide head. The top of its head slopes smoothly down to a pointed snout. Its eyes are a good size, but they do not have special eyelids that close. Its small mouth is curved and has grooves at the corners.

This shark has many rows of small, triangular teeth. These teeth are smooth and do not have extra points on the sides. It has five short pairs of gill slits. The last two pairs are located above its pectoral fins.

The pectoral fins are long and curved like a sickle. They end in narrow, pointed tips. The first dorsal fin (the fin on its back) is tall. It is placed a bit closer to the pectoral fins than to the pelvic fins (the fins on its belly). The pelvic fins are almost as big as the first dorsal fin. Male sharks have long, thin claspers on their pelvic fins. The second dorsal fin and the anal fin (near the tail) are very small. The second dorsal fin is in front of the anal fin.

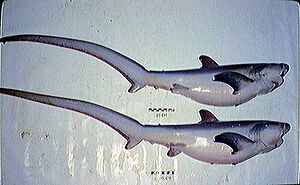

The common thresher's tail fin is very long. The upper part of the tail is about as long as the rest of the shark's body! This thin, curved tail points upwards and has a small notch near the tip.

Its skin is covered in tiny, overlapping scales called dermal denticles. Each scale has three ridges. The shark is metallic purplish-brown to gray on top. Its sides are more bluish. Its belly is white, and this white color extends over the bases of its pectoral and pelvic fins. This is different from the pelagic thresher, which has solid color on these fins. Sometimes, there is a white spot at the tips of its pectoral fins.

The common thresher is the largest thresher shark. It often reaches 5 meters (16 feet) long and weighs 230 kilograms (500 pounds). The longest one ever recorded was 5.7 meters (18.7 feet) long. Some very large ones might even weigh up to 900 kilograms (2,000 pounds)!

Where Do Common Threshers Live?

Common threshers live in both warm and cold waters all around the world. In the western Atlantic Ocean, you can find them from Newfoundland down to the Gulf of Mexico. They are rare north of New England. They also live from Venezuela to Argentina. In the eastern Atlantic, they are found from the North Sea and the British Isles to Ghana. This includes places like Madeira, the Azores, and the Mediterranean Sea. They also live from Angola to South Africa.

In the Indo-Pacific Ocean, these sharks are found from Tanzania to India and the Maldives. They also live near Japan, Korea, southeastern China, Sumatra, eastern Australia, and New Zealand. You can also find them around many Pacific islands like New Caledonia and the Hawaiian Islands. In the eastern Pacific, they have been seen from British Columbia to Chile. This includes the Gulf of California.

Common threshers travel a lot. They move to cooler areas when the water gets warm. For example, in the eastern Pacific, males travel further north than females. They can reach Vancouver Island in late summer and early fall. Young sharks usually stay in warm areas where they were born. In New Zealand, young sharks are found near the coast of the North and upper South Islands.

Scientists think there might be different groups of common threshers in different oceans. Even though they travel far, sharks from different areas do not seem to mix and have babies together very often.

What is the Common Thresher's Home Like?

Common threshers live in both coastal waters (near land) and the open ocean. They are usually found closer to land, especially young sharks. Young ones often stay in places like bays. They are mostly found within 30 kilometers (19 miles) of the coast. There are fewer of them further out at sea.

Most common threshers are seen near the surface of the water. However, they have been recorded diving down to at least 550 meters (1,800 feet) deep. One study tracked eight sharks off southern California. These sharks spent most of their time within 40 meters (130 feet) of the surface. But they would also dive much deeper, sometimes to 100 meters (330 feet) or more. In the tropical Marshall Islands, common threshers mostly spend their days at depths of about 160-240 meters (520-790 feet). The water there is about 18-20 °C (64-68 °F). Common threshers seem to like water temperatures between 16 and 21 °C (61 and 70 °F). But they can sometimes be found in water as cold as 9 °C (48 °F).

Life and Habits of the Common Thresher

Common threshers are very active and strong swimmers. Sometimes, they even leap completely out of the water! Like other fast sharks, they have a special red muscle along their sides. This muscle helps them swim powerfully and efficiently for a long time. They also have a special system of blood vessels that helps them keep their bodies warm. This means the temperature inside their red muscles is usually about 2 °C (3.6 °F) warmer than the ocean water. This helps them stay strong even in cooler waters.

Young common threshers can be eaten by bigger sharks. Adult common threshers do not have many known natural predators. However, killer whales have been seen eating them off New Zealand.

What Do Common Threshers Eat?

The common thresher uses its long upper tail fin to hit and stun its prey. About 97% of their diet is made up of bony fishes. They mostly eat small schooling fish like sardines, anchovys, mackerels, and herrings. Before they strike, the sharks swim around schools of fish. They splash the water with their tails to gather the fish closer together. They often do this in pairs or small groups. Threshers also eat larger, single fish like lancetfish. They also eat squid and other animals that live in the open ocean.

Off California, common threshers mostly eat northern anchovy. They also eat Pacific hake, Pacific sardine, Pacific mackerel, and market squid. During cold-water years, they focus on just a few types of prey. But during warmer El Niño periods, when there is less food, they are not as picky.

Many people have seen common threshers using their long tails to stun prey. They are often caught on longlines by their tails. This happens when they try to hit the bait with their tails. In 1914, a shark watcher named Russell J. Coles saw a thresher shark use its tail to flip fish into its mouth. In 1923, scientist W.E. Allen saw a 2-meter (6.6-foot) thresher shark chasing a fish. The shark swung its tail above the water like a whip, hurting the fish badly.

How Do Common Threshers Have Babies?

Like other mackerel sharks, common threshers give birth to live young. They usually have two to four pups in the eastern Pacific. In the eastern Atlantic, they have three to seven pups. They are thought to have babies throughout their range. One known place where they have babies is off southern California.

They usually breed in the summer, around July or August. The babies are born from March to June, after the mother has been pregnant for nine months. The baby sharks grow by eating eggs that the mother produces inside her body. The teeth of young embryos are small and not useful. They are covered by soft tissue. As the babies grow, their teeth become more like adult teeth. But they stay hidden until just before birth.

Newborn pups are usually 114 to 160 centimeters (3.7 to 5.2 feet) long. They weigh about 5 to 6 kilograms (11 to 13 pounds). Young sharks grow about 50 centimeters (20 inches) each year. Adults grow about 10 centimeters (4 inches) a year. The age at which they become adults can be different in different groups of sharks. In the eastern North Pacific, males become adults at 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) long and five years old. Females become adults at 2.6 to 4.5 meters (8.5 to 14.8 feet) long and seven years old. They are known to live for at least 15 years. Some scientists think they can live up to 45–50 years.

Common Threshers and People

Even though common threshers are large, they are not very dangerous to humans. Most divers say they are shy and hard to get close to underwater. The International Shark Attack File has only one record of a thresher shark attacking a person because it was provoked. There are also four records of them attacking boats, which probably happened when the sharks were trying to escape.

Fishing for Common Threshers

Common threshers are caught a lot by large fishing boats. These boats use longlines and big gillnets. This happens especially in the northwestern Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and the North Atlantic. Countries like Japan, Taiwan, Spain, and the United States catch them.

The meat of the common thresher is very popular. It can be cooked, dried and salted, or smoked. Their skin is used to make leather. Their liver oil is used for vitamins. Their fins are used for shark fin soup. In 2006, the United Nations reported that 411 metric tons of common threshers were caught worldwide.

In the United States, a special gillnet fishery for common threshers started in southern California in 1977. At first, there were only 10 boats. But within two years, there were 40 boats. The most sharks were caught in 1982, with 228 boats catching 1,091 metric tons. However, the common thresher population quickly dropped because of too much fishing. By the late 1980s, fewer than 300 metric tons were caught each year. The larger sharks almost disappeared.

Common threshers are still caught for sale in the United States. About 85% come from the Pacific Ocean and 15% from the Atlantic. Most are caught by the California-Oregon gillnet fishery. This fishery now focuses on catching swordfish, but they still catch threshers by accident. A small number of Pacific threshers are also caught with harpoons and other nets. In the Atlantic, threshers are mostly caught on longlines meant for swordfish and tuna.

Catching Threshers for Fun

Common threshers are very popular with sports fishers. They are known as one of the strongest fighting sharks, along with the shortfin mako shark. The International Game Fish Association considers them a game fish. Anglers use rods and reels to catch them off California, South Africa, and other places. Some fishers say thresher sharks are "exceedingly stubborn" and harder to catch than mako sharks.

Fishing for common threshers is similar to fishing for mako sharks. It is recommended to use a strong rod and a big reel with at least 365 meters (400 yards) of strong line. The best way to catch them is by trolling with baitfish. This means dragging the bait behind a boat, either deep or letting it float.

Protecting Common Threshers

In 2007, all three types of thresher sharks were listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This means they are at risk of becoming endangered. The quick drop in the California population showed that these sharks can be easily overfished. This is a concern in other areas where fishing data is not well reported. Besides fishing, common threshers are also caught by accident in other fishing gear like bottom trawls and fish traps. Fishermen who catch mackerel sometimes see them as a problem because they get tangled in their nets.

The United States has rules to manage common thresher fishing. These include limits on how many sharks can be caught by commercial fishers. There are also minimum sizes and limits for recreational fishers. It is against U.S. federal law to remove only the fins from sharks and throw the rest of the body back into the ocean.

After the common thresher population dropped in California, the number of fishing boats was limited to 70. Rules were also put in place about when and where they could fish. Some signs show that the California population is now recovering. Scientists estimate that the population could grow by 4–7% each year.

In New Zealand, the Department of Conservation says the common thresher shark is "Not Threatened."

Old Stories About Thresher Sharks

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (who lived from 384–322 BCE) wrote some of the first observations about the common thresher. He claimed that hooked threshers could free themselves by biting through fishing lines. He also said they protected their young by swallowing them. These "clever" behaviors led the ancient Greeks to call it alopex, which means "fox." This is where its modern scientific name comes from. However, science has not proven these stories to be true.

There is a common myth that common threshers work with swordfish to attack whales. In one version, the thresher shark swims around the whale and distracts it by splashing the water with its tail. This allows the swordfish to stab the whale in a weak spot with its long snout. Another story says the swordfish goes under the whale. Then, the thresher jumps out of the water and lands on top of the whale, pushing it onto the swordfish's snout. Some stories even say the thresher uses its tail to make "huge gashes" in the whale's side.

However, neither threshers nor swordfish eat whales. They also do not have the right teeth to do so. This story might have started because sailors mistook the tall dorsal fins of killer whales for thresher shark tails. Killer whales do attack large cetaceans (whales and dolphins). Also, swordfish bills have been found stuck in blue and fin whales. This was probably an accident because of how fast these fish swim. And while thresher sharks do some of the actions mentioned, they do not do them to attack whales.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |