Anders Johan Lexell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anders Lexell

|

|

|---|---|

Silhouette by F. Anting (1784)

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1740 Åbo, Finland

|

| Died | 11 December 1784 (aged 43) [OS: 30 November 1784] |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Alma mater | The Royal Academy of Turku |

| Known for | Calculated the orbit of Lexell's Comet Calculated the orbit of Uranus |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematician Physicist Astronomer |

| Institutions | Uppsala Nautical School Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences |

| Doctoral advisor | Jakob Gadolin |

| Other academic advisors | M. J. Wallenius |

| Influences | Leonhard Euler |

Anders Johan Lexell (born December 24, 1740 – died December 11, 1784) was a famous Finnish-Swedish astronomer, mathematician, and physicist. He spent most of his life working in Imperial Russia. There, he was known as Andrei Ivanovich Leksel.

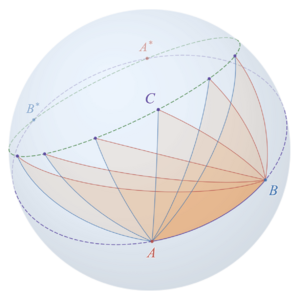

Lexell made important discoveries in areas like polygonometry (the study of polygons) and celestial mechanics (the study of how planets and comets move). One of his biggest achievements was calculating the path of a comet that was later named after him. He was also known for his work on spherical trigonometry, which helped him understand the movement of comets and planets. A special rule for spherical triangles is also named after him.

Lexell was a very active member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He published 66 papers in just 16 years! The famous mathematician Leonhard Euler highly praised Lexell's work. Another scientist, Daniel Bernoulli, also admired Lexell, saying his work was "profound and interesting."

Lexell never married. He was a close friend of Leonhard Euler and his family. He was even with Euler when he passed away. Lexell took over Euler's position as the head of the mathematics department at the Russian Academy of Sciences. Sadly, Lexell himself died the very next year. An asteroid called 2004 Lexell and a lunar crater called Lexell are named in his honor.

Contents

Life Story

Early Years

Anders Johan Lexell was born in Turku, Finland. His father, Johan Lexell, was a goldsmith and a local officer. When Anders was 14, he started studying at the Academy of Åbo. In 1760, he earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree. His main teacher was Jakob Gadolin. In 1763, Lexell moved to Uppsala, Sweden. He worked there as a mathematics lecturer at Uppsala University. By 1766, he became a professor of mathematics at the Uppsala Nautical School.

Working in St. Petersburg

In 1762, Catherine the Great became the ruler of Russia. She wanted to make Russia a center for science. She invited the famous mathematician Leonhard Euler to come to St. Petersburg. After Euler returned to Russia, he suggested that the Russian Academy of Sciences invite Lexell. Euler wanted Lexell to study mathematics and how it applied to astronomy, especially spherical geometry. Lexell was very interested in this opportunity. He also wanted to help with the observations of the 1769 transit of Venus. This event was going to be watched from eight different places across the huge Russian Empire.

To join the Russian Academy of Sciences, Lexell wrote a paper on integral calculus in 1768. Euler reviewed the paper and praised it highly. Because of this, Lexell was invited to join the Academy as a mathematics assistant. He accepted the offer. In the same year, the Swedish king allowed him to leave Sweden, and he moved to St. Petersburg.

His first job was to learn about the astronomical tools. These tools would be used to watch the 1769 transit of Venus. He helped observe this event in St. Petersburg. He worked alongside Christian Mayer.

Lexell greatly helped in understanding the Lunar theory (the moon's movement). He also helped figure out the parallax of the Sun. This was based on the observations from the transit of Venus. His work was recognized by many. In 1771, he became an academician (a full member) of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Astronomy. He also became a member of other important academies in Sweden and France.

Travels Abroad

In 1775, the Swedish King offered Lexell a professor position at the University of Åbo. However, he was allowed to stay in St. Petersburg for three more years to finish his work. This permission was extended even longer. By 1780, Lexell was supposed to return to Sweden. This would have been a big loss for the Russian Academy of Sciences. So, the Academy suggested he travel to Germany, England, and France. After that, he could return to St. Petersburg through Sweden. Lexell agreed to the trip. To the Academy's delight, he was allowed to stay in St. Petersburg permanently. He returned in 1781, very happy with his journey.

Sending scientists abroad was not common back then. Lexell was eager to go. He was asked to write down his travel plans. His goals were to visit major observatories and learn how they were built. He also wanted to see their scientific instruments. If he found anything new, he was supposed to buy the plans. He also needed to learn about cartography (map-making). He was asked to get new geographic, hydrographic, military, and mineralogic maps. He also had to write letters to the Academy regularly. These letters would report interesting news about science, arts, and literature.

Lexell left St. Petersburg in July 1780 by sailing ship. He arrived in Berlin, Germany, and stayed there for a month. He then traveled to Potsdam. In September, he went to Bavaria, visiting cities like Leipzig and Göttingen. In October, he traveled to Straßbourg and then to Paris, where he spent the winter. In March 1781, he moved to London. In August, he left London for Belgium. He visited Flanders and Brabant. Then he went to the Netherlands, visiting The Hague and Amsterdam. He returned to Germany in September. He visited Hamburg and then sailed to Sweden. He spent three days in Kopenhagen on the way. In Sweden, he visited his hometown of Åbo, and also Stockholm and Uppsala. In early December 1781, Lexell returned to St. Petersburg. He had been traveling for almost a year and a half.

Lexell wrote 28 letters during his trip to Johann Euler, Leonhard Euler's son. These letters often described the places and people he met. They also shared his impressions of his travels.

Last Years

Lexell became very close to Leonhard Euler. In his later years, Euler lost his eyesight. But he kept working with the help of his elder son, Johann Euler, who read to him. Lexell helped Euler a lot, especially with applying mathematics to physics and astronomy. He helped Euler with calculations and preparing papers. On September 18, 1783, after lunch with his family, Euler was talking with Lexell. They were discussing the newly found planet Uranus and its orbit. Euler suddenly felt sick and passed away a few hours later.

After Euler's death, Princess Dashkova, the Director of the Academy, appointed Lexell as Euler's replacement in 1783. Lexell also became a member of the Turin Royal Academy. The London Board of Longitude added him to their list of scientists who received their scientific papers.

Lexell did not get to enjoy his new position for long. He died on November 30, 1784.

Scientific Contributions

Lexell is best known for his work in astronomy and celestial mechanics. But he also worked in many other areas of mathematics. These included algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. He published 62 works during his 16 years at the Russian Academy of Sciences. He also co-authored 4 more papers with other scientists like Leonhard Euler and Christian Mayer.

Polygonometry

Polygonometry was a big part of Lexell's work. This field uses trigonometry to solve problems about simple polygons (shapes with straight sides). Lexell developed a general way to solve polygons. He looked at two types of problems. The first type had polygons defined by their sides and angles. The second type used their diagonals and the angles between them. He created general formulas to solve polygons with any number of sides. He also showed how to classify these problems.

Celestial Mechanics and Astronomy

Lexell's first major work at the Russian Academy of Sciences was analyzing data from the 1769 transit of Venus. He published several papers and a book in 1772 about figuring out the parallax of the Sun.

He also helped Euler finish his Lunar theory, which explains the moon's movements. Lexell was even listed as a co-author on Euler's 1772 book, "Theoria motuum Lunae."

After that, Lexell focused a lot on comet astronomy. He calculated the paths of many newly discovered comets. One of the most famous was a comet found by Charles Messier in 1770. Lexell calculated its path and showed that it had been much further from the Sun before it passed near Jupiter in 1767. He also predicted that after it met Jupiter again in 1779, it would be thrown out of the inner Solar System. This comet was later named Lexell's Comet.

Lexell was also the first to calculate the path of Uranus. He proved that it was a planet and not a comet. He made his first calculations while traveling in Europe in 1781. These were based on observations by Hershel and Maskelyne. When he returned to Russia, he made more precise calculations. He found an old record of a "star" observed in 1759 by Christian Mayer. This "star" was not in later catalogs. Lexell thought it might be an earlier sighting of Uranus. Using this old data, he calculated the exact path, which turned out to be an ellipse. This proved that the new object was indeed a planet. Lexell also estimated the planet's size more accurately than others at the time. He noticed that Uranus's orbit was being slightly changed, or perturbed. He suggested that there might be other planets in the Solar System that were causing these changes.

See also

In Spanish: Anders Johan Lexell para niños

In Spanish: Anders Johan Lexell para niños

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |