Gallipoli campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gallipoli campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of the First World War | |||||||

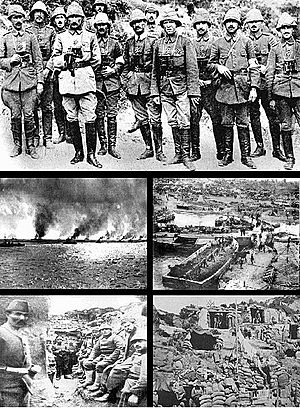

A collection of photographs from the campaign. From top and left to right: Ottoman commanders including Mustafa Kemal (fourth from left); Entente warships; V Beach from the deck of SS River Clyde; Ottoman soldiers in a trench; and Entente positions |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by: |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

Egyptian Labour Corps Maltese Labour Corps |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5 divisions (initial)

Supported by: |

6 divisions (initial)

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total: 300,000 (56,707 dead) |

Total: 255,268 (56,643 dead) |

||||||

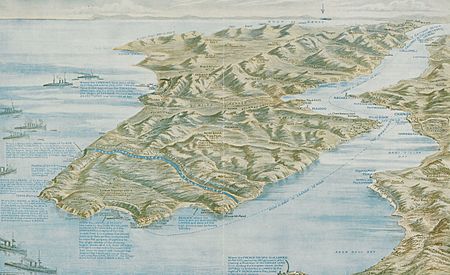

The Gallipoli campaign was a major military event during the First World War. It took place on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey from February 1915 to January 1916. The main goal for the Entente powers (Britain, France, and Russia) was to weaken the Ottoman Empire. They wanted to take control of the Ottoman straits, especially the Dardanelles. This would allow their warships to reach Constantinople (now Istanbul), the Ottoman capital. It would also open a supply route through the Black Sea to Russia.

The Entente fleet tried to force their way through the Dardanelles in February 1915 but failed. After this, soldiers were landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915. The fighting lasted for eight months. Both sides suffered huge losses, with about 250,000 casualties each. In January 1916, the Entente forces gave up and left.

The campaign was a big victory for the Ottoman Empire. In Turkey, it is seen as a very important moment in their history. It showed their strong defense of their homeland. This struggle also helped lead to the Turkish War of Independence. Eight years later, the Republic of Turkey was formed. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a key commander at Gallipoli, became its founder and first president.

For Australia and New Zealand, the campaign is often seen as the start of their national consciousness. The anniversary of the landings, April 25, is called Anzac Day. It is the most important day to remember military casualties and veterans in both countries.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Ottoman Empire Joins the War

The Ottoman Empire joined the First World War on October 29, 1914. Two former German warships, now part of the Ottoman navy, attacked the Russian port of Odessa. This led to the Ottomans fighting against Russia in the Caucasus campaign. Britain then briefly attacked forts in Gallipoli. They also thought about trying to force their way through the Dardanelles.

Entente Plans for the Dardanelles

The British and French were fighting in trench warfare on the Western Front. Trade routes to Russia were blocked by Germany and Austria-Hungary. The White Sea and Sea of Okhotsk were frozen in winter. The Baltic Sea was blocked by the German navy. The entrance to the Black Sea through the Dardanelles was controlled by the Ottoman Empire. They had even placed mines in the waterway.

Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the British navy, suggested a naval attack on the Dardanelles. He wanted to use older battleships that were not needed against the German fleet. He hoped attacking the Ottomans would also bring Bulgaria and Greece into the war on the Entente side. Russia asked Britain for help against the Ottomans. So, planning began for a naval show of force in the Dardanelles. This was meant to draw Ottoman troops away from the Caucasus.

The first attack on the Dardanelles began on February 19, 1915. British and French ships started firing at Ottoman coastal forts. Bad weather slowed them down. But by February 25, the outer forts were destroyed, and the entrance was cleared of mines.

Churchill pushed the naval commander, Admiral Sackville Carden, to try harder. Carden believed the fleet could reach Istanbul in 14 days. But he became ill from stress. Admiral John de Robeck took over command.

March 18, 1915: A Costly Day

On March 18, 1915, the Entente fleet, with 18 battleships, launched a big attack. They aimed for the narrowest part of the Dardanelles. Ottoman fire damaged some Entente ships. Minesweepers were sent in but had to retreat under fire.

The French battleship Bouvet hit a mine and sank in two minutes. Only 75 men out of 718 survived. The British ships Irresistible and Inflexible also hit mines. Irresistible sank, and Inflexible was badly damaged. Another British ship, Ocean, was sent to help Irresistible but also hit a mine and sank.

The French battleships Suffren and Gaulois were also damaged. They sailed through a new line of mines secretly placed by the Ottoman ship Nusret ten days earlier. Because of these losses, Admiral de Robeck ordered his fleet to retreat. The Entente stopped trying to force the straits by sea. They decided to capture the Turkish defenses by landing troops on land instead.

Preparing for Landings

Entente Forces Get Ready

After the naval attacks failed, troops were gathered. Their job was to destroy the Ottoman artillery that was stopping the minesweepers. General Sir Ian Hamilton was put in charge of the 78,000 men of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF).

Soldiers from Australia and New Zealand (called the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps or ANZAC) were training in Egypt. They joined British and French troops. Hamilton planned to land his forces at Cape Helles and Seddülbahir, at the southern tip of the peninsula. The Entente leaders did not think the Ottoman soldiers would fight very well.

The troops were loaded onto ships in the wrong order for landing. This caused a long delay. Many troops had to go to Alexandria to re-embark. This five-week delay gave the Ottomans time to make their defenses stronger.

The ANZAC Corps gathered on the Greek island of Lemnos on April 12. They practiced landings there. On April 17, a British submarine, HMS E15, tried to go through the straits. It hit a submarine net and was shelled, killing its commander and six crew.

Ottoman Forces Prepare

The Ottoman force ready to stop a landing was the 5th Army. This army had five divisions and was led by Otto Liman von Sanders, a German general. Many senior officers were also German.

Ottoman commanders agreed that holding the high ground on the peninsula's ridges was the best defense. Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal knew the Gallipoli peninsula well. He predicted that Cape Helles and Gaba Tepe were likely landing spots.

Sanders kept most of his forces inland as a reserve. He left only a few troops guarding the coast. Roads were built, and small boats were made to move troops quickly. Beaches were covered with barbed wire, and mines were made from torpedo parts. Trenches and gun positions were dug along the beaches.

The time the British took to organize the landings helped the Ottomans. Sanders later said, "the British allowed us four good weeks of respite for all this work." Ottoman aircraft also flew reconnaissance missions over Mudros. They watched the British naval force gathering.

The Landings Begin

The Entente planned to land troops, capture Ottoman forts and artillery, and then let the naval force go through to Istanbul. The landings were set for April 23 but were delayed until April 25 due to bad weather.

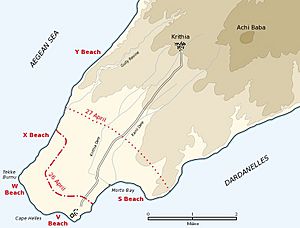

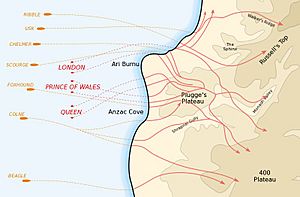

The 29th Division was to land at Helles, at the tip of the peninsula. The ANZACs were to land north of Gaba Tepe on the Aegean coast. From there, they would advance across the peninsula to cut off Ottoman troops. This area became known as ANZAC. The British and French area was called Helles. The French also made a fake landing at Kum Kale on the Asian shore to distract the Ottomans.

ANZAC Cove Landing

The ANZAC force had about 25,000 men. They were supposed to land and move inland to cut Ottoman communication lines. The 1st Australian Division would land first.

At about 2:00 a.m. on April 25, an Ottoman observer saw many ships far away. By 3:00 a.m., the moon was covered, and the ships were gone. The Ottomans were not sure if it was a real landing or a trick. When heavy artillery was heard around 6:00 a.m., more Ottoman troops were sent to the area.

At 4:00 a.m., the first wave of Australian troops began moving to shore. They landed about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) too far north, in a bay south of Ari Burnu. This was due to currents or a navigation mistake. The landing was harder because the ground rose steeply from the beaches. Only two Ottoman companies were defending the spot. But they caused many casualties before being defeated.

The rough land made it hard for the Australians to move inland together. Many groups got lost. Some reached the second ridge, but few reached their goals. By mid-morning, Mustafa Kemal had organized the defenders for a counter-attack. By evening, the Australian and New Zealand commanders wanted to re-embark. But the navy said it was impossible. So, the troops were ordered to dig in.

ANZAC casualties on the first day were around 2,000 killed or wounded. The failure to capture the high ground led to a stalemate. The landing was contained in a small area.

Cape Helles Landing

The Helles landing was done by the 29th Division. They landed on five beaches, named "S", "V", "W", "X", and "Y" from east to west. At "Y" Beach, the Entente landed without opposition and moved inland. But the commander pulled his force back to the beach, missing a chance to advance.

The main landings were at "V" Beach and "W" Beach. At "V" Beach, troops landed from a converted ship, SS River Clyde. It was run aground so troops could disembark. At "W" Beach, troops landed in open boats. On both beaches, Ottoman defenders were in strong positions. They caused many casualties as the British infantry landed. Of the first 200 soldiers from River Clyde, only 21 reached the beach.

The Ottoman defenders were too few to stop the landing. But they caused many casualties and kept the attack close to the shore. By the morning of April 25, the 57th Infantry Regiment had run out of ammunition. Mustafa Kemal ordered them: "I do not order you to fight, I order you to die." Every man of the regiment was killed or wounded.

At "W" Beach, the British managed to overcome the defenders. Six Victoria Crosses were given to soldiers there. After the landings, the Entente did little to push forward. The Ottomans had time to bring in more troops.

Fighting on Land Continues

Early Battles and Stalemate

On April 27, the Ottoman 19th Division counter-attacked the Entente at Anzac. With naval gunfire support, the Entente held them back. On April 28, the Entente fought the First Battle of Krithia to capture a village. But the attack failed, with 3,000 casualties.

As more Ottoman troops arrived, the chance of a quick Entente victory disappeared. The fighting at Helles and Anzac became a long, difficult battle. On April 30, the Royal Naval Division landed. That afternoon, Ottoman troops counter-attacked at Helles and Anzac. The attacks were stopped by heavy Entente machine-gun fire, causing many Ottoman casualties.

On April 30, the Australian submarine HMAS AE2 was sunk by an Ottoman torpedo boat. Its crew was captured. However, other British and French submarines were successful. They disrupted Ottoman communications and sank several ships. This made it harder for the Ottomans to send supplies and troops.

May 1915 Operations

On May 6, the Entente launched the Second Battle of Krithia. It involved 20,000 men. The attack began after 30 minutes of artillery fire. The British and French advanced but became separated. They came under heavy fire and the attack stopped. The next day, reinforcements continued the advance.

The attack continued on May 7 and 8. Australian and New Zealand troops advanced quickly. But the attack failed to take Krithia or Achi Baba. Both sides then strengthened their defenses.

On May 19, 42,000 Ottoman troops attacked Anzac. They wanted to push the 17,000 Australians and New Zealanders back into the sea. But British aircraft spotted their preparations. The Ottomans suffered about 13,000 casualties, with 3,000 killed. Australian and New Zealand casualties were 160 killed and 468 wounded.

Ottoman losses were so severe that a truce was arranged on May 24. This was to bury the dead in no man's land. This led to a friendly feeling between the armies, like the Christmas truce on the Western Front.

The British lost some battleships to Ottoman torpedoes and German submarines. This greatly reduced the Entente's naval firepower. Most warships were moved to a safer area.

June and July 1915 Operations

In the Helles sector, the Entente attacked Krithia and Achi Baba again on June 4. This was the Third Battle of Krithia. The attack was stopped. This ended any chance of a decisive breakthrough. Trench warfare continued, with very small gains. Both sides suffered about 25 percent casualties.

In June, the Entente air effort increased. The 52nd (Lowland) Division also landed at Helles. They fought in the Battle of Gully Ravine on June 28. This gained some ground for the British. Between July 1 and 5, the Ottomans counter-attacked several times but failed to get the lost ground back. On July 12, two fresh brigades attacked again. They gained very little ground and lost many men.

August Offensive: A Last Big Push

The Entente had failed to capture Krithia. So, Hamilton made a new plan. He wanted to capture the Sari Bair Range of hills and Hill 971. Both sides had received more troops. The Entente now had 15 divisions, and the Ottomans had 16.

The Entente planned to land two new divisions at Suvla, 5 kilometers (3 miles) north of Anzac. Then they would advance on Sari Bair from the north-west. At Anzac, an attack would be made against the Sari Bair range. This would involve attacking Baby 700 from the Nek and Chunuk Bair.

The landing at Suvla Bay happened on the night of August 6. There was little opposition. But the British commander did not push his troops to advance inland. So, little more than the beach was captured. The Ottomans quickly took the Anafarta Hills. This stopped the British from moving inland. The Suvla front became static trench warfare.

The offensive began with distractions. At Helles, the Battle of Krithia Vineyard was another costly stalemate. At Anzac, the Battle of Lone Pine captured the main Ottoman trench line. But the attacks at Chunuk Bair and Hill 971 failed.

The New Zealand Infantry Brigade got very close to Chunuk Bair by dawn on August 7. But they did not take the summit until the next morning. An attack at the Nek by Australian light horsemen failed with heavy losses. An attack on Hill 971 never happened. The New Zealanders held Chunuk Bair for two days. But an Ottoman counterattack on August 10, led by Mustafa Kemal, drove them off the heights. This was the Entente's best chance of victory, and it was lost.

The last British attempt to restart the offensive was on August 21. This was the Battle of Scimitar Hill and the Battle of Hill 60. Controlling these hills would have connected the Anzac and Suvla fronts. But these attacks also failed.

Conditions at Gallipoli became very bad. Summer heat and poor sanitation led to many flies. Eating was difficult. A dysentery epidemic spread through the trenches. Both sides suffered greatly from disease.

Leaving Gallipoli

After the August Offensive failed, the Gallipoli campaign slowly ended. Public opinion in Britain turned against the campaign. General Hamilton was replaced. Autumn and winter brought gales, blizzards, and floods. Many men drowned or froze to death. Thousands suffered frostbite.

Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. This opened a land route between Germany and the Ottoman Empire. The Germans sent heavy artillery, modern aircraft, and experienced crews to the Ottomans. This made the Ottoman defenses much stronger.

The British Cabinet decided to evacuate in early December. Many casualties were expected during the evacuation. But clever tricks were used to hide the departure. For example, William Scurry invented a self-firing rifle. It was set up to fire by water dripping into a pan attached to the trigger. This made the Ottomans think the trenches were still occupied.

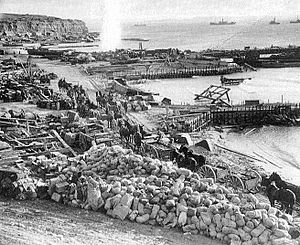

At Anzac Cove, troops stayed silent for an hour. When curious Ottoman troops came to check, the Anzacs opened fire. This stopped the Ottomans from checking when the real evacuation happened. A mine was set off at the Nek, killing 70 Ottoman soldiers. The Entente forces left with almost no casualties. But large amounts of supplies were left behind.

Helles was held for a while longer. But the decision to evacuate was made on December 28. The Ottomans were looking for signs of withdrawal this time. On January 7, 1916, the Ottomans attacked the British at Gully Spur. But the attack failed. Mines were set with timers. On the night of January 7/8, British troops began to retreat to the beaches. They used makeshift piers to board boats. The last British troops left from Lancashire Landing around 4:00 a.m. on January 8, 1916. The Newfoundland Regiment was part of the rearguard and left on January 9, 1916.

Despite predictions of up to 30,000 casualties, the evacuation was very successful. 35,268 troops, 3,689 horses and mules, 127 guns, and much equipment were removed. Some animals that could not be taken were killed. Many supplies and damaged equipment were left behind. Soon after dawn, the Ottomans retook Helles.

What Happened After

Military Impact

Historians have different views on the campaign's outcome. Some call it a defeat for the Entente. Others say it was a stalemate. The campaign did cause "enormous damage" to Ottoman resources. But the Entente failed to achieve its main goal of controlling the Dardanelles.

The Entente campaign suffered from unclear goals and poor planning. They had too little artillery, inexperienced troops, and bad maps. The geography also played a big part. The Ottomans used the high ground around the landing beaches to set up strong defenses. This kept the Entente forces stuck on narrow beaches.

British and French submarine operations in the Sea of Marmara were a success. They forced the Ottomans to stop using the sea for transport. This caused problems for Ottoman supplies and morale.

The Gallipoli campaign ended the careers of some commanders. But it helped others, like Australian brigade commanders John Monash and Harry Chauvel, get promoted. The campaign gave the Ottomans confidence in their ability to defeat the Entente.

The lessons from Gallipoli were studied for future amphibious operations. These included the Normandy Landings in 1944. The campaign also influenced US Marine Corps operations during the Pacific War.

Political Effects

Political problems in Britain started during the battle. Churchill was demoted and later resigned. The British government faced criticism for the failure at Gallipoli. An investigation, the Dardanelles Commission, was set up. It found that the campaign's success depended on the government giving it priority. It also found that Hamilton had been too optimistic.

Casualties of the Campaign

| Countries | Dead | Wounded | Missing or POW |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Empire |

56,643 | 97,007 | 11,178 | 164,828 |

| United Kingdom | 34,072 | 78,520 | 7,654 | 120,246 |

| France | 9,798 | 17,371 | — | 27,169 |

| Australia | 8,709 | 19,441 | — | 28,150 |

| New Zealand | 2,721 | 4,752 | — | 7,473 |

| British India | 1,358 | 3,421 | — | 4,779 |

| Newfoundland | 49 | 93 | — | 142 |

| Total (Entente) | 56,707 | 123,598 | 7,654 | 187,959 |

Casualty numbers vary, but over 100,000 men were killed in the Gallipoli Campaign. This included 56,000–68,000 Ottoman soldiers and about 53,000 British and French soldiers. Many soldiers also got sick due to unsanitary conditions. Diseases like typhoid and dysentery were common. About 90,000 British Empire soldiers were evacuated due to illness.

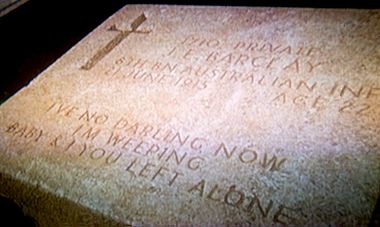

Graves and Memorials

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) maintains 31 cemeteries on the Gallipoli peninsula. Many soldiers who died on hospital ships and were buried at sea have no known grave. Their names are on "memorials to the missing." The Lone Pine Memorial remembers Australians and New Zealanders. The Helles Memorial remembers British, Indian, and Australian troops.

There are also three CWGC cemeteries on the Greek island of Lemnos. This island was a hospital base for the Entente forces. There is a French cemetery on the Gallipoli Peninsula. There are no large Ottoman/Turkish military cemeteries on the peninsula. But there are many memorials, like the Çanakkale Martyrs' Memorial.

After the Campaign

Entente troops were moved to Lemnos and then to Egypt. French forces were later used in Salonika, Greece. In Egypt, British Imperial and Dominion troops from Gallipoli formed the new Egyptian Expeditionary Force. Many of these units later fought on the Western Front.

The Sinai and Palestine campaign followed. British and Australian mounted units took part. The Sinai Peninsula was retaken in 1916. Palestine and the northern Levant were captured from the Ottoman Empire by 1918. The Ottoman Empire was later divided. The occupation ended in 1923 after the Turkish War of Independence.

Legacy of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli campaign is very important in Australia and New Zealand. It is seen as a "baptism of fire" and linked to their growth as independent nations. About 50,000 Australians and 16,000 to 17,000 New Zealanders served there. The campaign helped create a unique Australian identity. This is often linked to the "Anzac spirit" of the soldiers.

The landing on April 25 is remembered every year as "Anzac Day". It is a national holiday in both countries. Veterans march, and dawn services are held. Thousands of tourists visit Gallipoli for the dawn service there. Anzac Day is the most important day to remember military casualties and veterans in Australia and New Zealand.

-

Anzac Day march in Wagga Wagga, Australia, in 2015

-

The Çanakkale 1915 Bridge on the Dardanelles strait, connecting Europe and Asia, is the longest suspension bridge in the world.

-

The Australian Turkish Friendship Memorial in Kings Domain, Melbourne honours WWI fallen soldiers and is a tribute to Australian-Turkish relations

Many streets, places, and buildings are named after the campaign. This is especially true in Australia and New Zealand. The campaign also had a big impact on popular culture, like films and songs. The song "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda" by Eric Bogle tells the story of a young Australian soldier injured at Gallipoli. It is a famous anti-war song.

In Turkey, the battle is a key event in the country's history. It is mainly remembered for the fighting around the port of Çanakkale. There, the Royal Navy was stopped in March 1915. For Turks, March 18 is as important as April 25 is for Australians and New Zealanders. The campaign's main importance for Turks is the rise of Mustafa Kemal. He became the first president of the Republic of Turkey. The phrase "Çanakkale geçilmez" (Çanakkale is impassable) shows the country's pride. The song "Çanakkale içinde" (A Ballad for Chanakkale) remembers the Turkish youth who died in the battle.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Galípoli para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Galípoli para niños

- Timeline of the Gallipoli Campaign

- Gallipoli, a 1981 Australian film directed by Peter Weir

- Çanakkale 1915, a 2012 Turkish film based on some of the major political events of the Gallipoli campaign

- The Water Diviner, a 2014 Australian film directed by Russell Crowe

- Gallipoli Star, a military decoration of the Ottoman Empire

- "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda", a 1971 song by Eric Bogle

- Gallipoli Art Prize, awarded annually by the Gallipoli Memorial Club

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |