Dionysus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dionysus

(Bacchus) |

|

|---|---|

| God of wine, vegetation, fertility, festivity and theatre | |

| Member of the Twelve Olympians | |

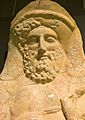

Marble bust of youthful Dionysus. Knossos, second century AD. Archaeology museum of Heraklion.

|

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Animals | Bull, panther, tiger or lion, goat, snake |

| Symbol | Thyrsus, grapevine, ivy, theatrical masks |

| Festivals | Bacchanalia (Roman), Dionysia |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Ariadne |

| Children | Priapus, Hymen, Thoas, Staphylus, Oenopion, Comus, Phthonus, the Graces, Deianira |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Angelos, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, Tantalus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Bacchus, Liber |

| Etruscan equivalent | Fufluns |

| Egyptian equivalent | Osiris |

| This article contains special characters. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols. |

Dionysus is a famous god in ancient Greek religion and myth. He is known as the god of the grape-harvest, making wine, plants, and having fun at parties and in the theatre. The Greeks also called him Bacchus, a name later used by the Romans.

People say Dionysus taught humans how to use oxen to plow fields instead of doing it by hand. Because of this, his followers often showed him with horns.

In some stories, Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Persephone. In others, he was the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Semele. Many tales say he was born in Thrace, traveled widely, and then came to Greece as a visitor.

Festivals for Dionysus included sacred plays that told his myths. These plays helped start the development of theatre in Western culture. Dionysus was also seen as a link between the living and the dead.

The Romans connected Bacchus with their own god, Liber Pater. Liber Pater was the "Free Father" and was honored during the Liberalia festival. He was the protector of winemaking, wine, and male fertility.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Dionysus comes from ancient Greek. The first part, dio-, has always been linked to Zeus. Zeus's name in an older Greek language was di-wo.

The second part of the name, -nūsos, is a bit of a mystery. It might be connected to Mount Nysa. This mountain is said to be where Dionysus was born and raised by nymphs (nature spirits). Some experts believe nūsē is a word from the Thracian language, meaning "Dionysus" would mean "son of Zeus."

Other scholars think the name comes from a language spoken in Greece before Greek. This is because it's hard to find a clear link to other ancient European languages.

How Old is Dionysus?

New findings show that Dionysus was one of the earliest gods in mainland Greek culture. The first written records of people worshiping Dionysus are from Mycenaean Greece, around 1300 BC.

The oldest known picture of Dionysus, with his name written next to it, is on a large mixing bowl called a dinos. This bowl was made by the potter Sophilos around 570 BC and is now in the British Museum. By the 600s BC, pictures on pottery show that Dionysus was already seen as more than just a god of wine. He was also linked to weddings, death, and sacrifices. His group of followers, including satyrs and dancers, was already well-known.

Exciting Myths of Dionysus

In the ancient world, there were many different stories about how Dionysus was born and lived. By the 1st century BC, people tried to combine these stories into one main tale. This story included not just one birth, but two or even three times the god appeared on Earth.

The historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that some storytellers said there were two gods named Dionysus. An older one was the son of Zeus and Persephone. The younger one then took on the older one's adventures. So, later people thought there was only one Dionysus because their names were the same. He also said that Dionysus was seen in "two forms." The older one had a long beard, like all men in early times. The younger one was young and beardless.

His First Birth

According to Diodorus, Dionysus was first the son of Zeus and Persephone. In some versions, he was the son of Zeus and Demeter. This first Dionysus was killed by the Titans and then reborn.

The myth says that baby Dionysus was taken to Mount Ida. There, he was protected by the dancing Curetes. Zeus wanted Dionysus to take his place as ruler of the universe. But Hera, Zeus's jealous wife, encouraged the Titans to kill the child.

Other stories say Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of farming. When the Titans tore Dionysus apart, Demeter gathered his body parts, and he was born again.

His Second Birth

Another birth story says that Dionysus was originally the son of Zeus and Persephone. When the Titans tore him apart, Zeus took the pieces of his heart. He put them into a drink and gave it to Semele. Semele was the daughter of Harmonia and Cadmus, the king and founder of Thebes.

Semele then had a dream. In her dream, Zeus destroyed a fruit tree with lightning but didn't harm the fruit. He sent a bird to bring him one of the fruits and sewed it into his thigh. This meant he would be both mother and father to the new Dionysus. She saw a bull-shaped man come out of his thigh and realized she had been the tree. Her father, Cadmus, was scared by the dream and told Semele to make sacrifices to Zeus.

Zeus then came to Semele disguised as a snake. He told her to be happy: "You will have a son who will not die, and I will call you immortal. Happy woman! You have imagined a son who will make people forget their troubles. You will bring joy to gods and men."

Semele was thrilled to know her son would be divine. She dressed in flowers and ivy and would run barefoot to the meadows and forests when she heard music. Hera became jealous. She feared Zeus would replace her with Semele as queen of Olympus.

Hera went to Semele disguised as an old woman. She made Semele jealous of the attention Zeus gave to Hera. She tricked Semele into asking Zeus to appear to her in his full god form. Zeus warned her that no other mortals had ever seen him with his lightning bolts. Semele reached out to touch them and was burned to ash. But baby Dionysus survived! Zeus saved him from the flames and sewed him into his thigh. Later, Dionysus was born from Zeus's thigh.

According to an Egyptian story, Dionysus is the son of Ammon and Amaltheia. When Dionysus was born, Ammon worried his wife, Rhea, would find the child. So, he took baby Dionysus to Nysa, where Dionysus traditionally grew up. Ammon brought Dionysus into a cave where Nysa, a hero's daughter, cared for him. Dionysus became famous for his artistic skills, beauty, and strength. It is said he discovered how to make wine when he was a boy. His fame reached Rhea, who was angry with Ammon for his trick. She tried to control Dionysus but couldn't. So, she left Ammon and married Cronus.

When Dionysus grew up, he discovered how to grow grapevines and make wine. He was the first to do this. He then traveled, teaching people how to grow grapes.

Other Famous Myths

Midas' Golden Touch

One myth tells how Dionysus found that his old teacher and foster father, Silenus, was missing. Silenus had wandered off and was found by some farmers. They took him to their king, Midas. The king recognized Silenus and hosted him for ten days and nights. On the eleventh day, Midas brought Silenus back to Dionysus. Dionysus was happy to see Silenus and told the king he could wish for anything he wanted.

Midas wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. Dionysus agreed. Midas quickly tested his new power. He touched an oak branch and a stone, and they turned to gold. But his happiness disappeared when his bread, meat, and wine also turned to gold. Later, when his daughter hugged him, she also turned to gold.

The king was horrified and wanted to get rid of his Midas Touch. He prayed to Dionysus to save him from starving. The god agreed, telling Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. After he did, the river sands turned to gold.

How Dionysus is Shown in Art

Symbols

The earliest pictures of Dionysus show him as a grown man with a beard and robes. He holds a staff made of fennel, with a pine-cone on top. This staff is called a thyrsus. Later pictures show him as a young man without a beard. He often wears the skin of a panther or leopard.

His parade, called a thiasus, includes wild female followers (maenads) and bearded satyrs who dance or play music. The god himself rides in a chariot, usually pulled by exotic animals like lions or tigers.

Dionysus was also strongly linked to the bull and to trees, especially the fig tree. The snake was a symbol of Dionysus in ancient Greece and of Bacchus in Greece and Rome.

In Ancient Art

Dionysus, and especially his followers, were often shown on the painted pottery of Ancient Greece. Much of this pottery was made to hold wine. But, apart from some carvings of maenads, Dionysian subjects were not often seen in large sculptures until the Hellenistic period. After that, they became common.

Well-known Hellenistic sculptures of Dionysian subjects, which we know from Roman copies, include the Barberini Faun and the Belvedere Torso. The Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus show related themes that became part of the Dionysian world. The marble Dancer of Pergamon is an original, as is the bronze Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, found recently in the sea.

The Lycurgus Cup from the 300s AD, in the British Museum, is a special glass cup. It changes color when light shines through it. It shows King Lycurgus tied up, being teased by the god and attacked by a satyr. This cup might have been used for celebrations of Dionysian mysteries.

Dionysus in Later Art

Art about Bacchus became popular again during the Italian Renaissance. It was almost as popular as it was in ancient times. Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne (1522–23) and The Bacchanal of the Andrians (1523–26) were both painted for the same room. They show a grand, peaceful scene. Meanwhile, Diego Velázquez in The Triumph of Bacchus (or Los borrachos – "the drinkers", around 1629) and Jusepe de Ribera in his Drunken Silenus chose a more realistic style. Flemish Baroque painting often showed Bacchus's followers, like in Van Dyck's Drunken Silenus and many works by Rubens. Poussin also often painted scenes with Bacchus.

A common theme in art from the 1500s onwards was showing Bacchus and Ceres (the goddess of grain) taking care of a symbol of love, often Venus, Cupid, or Amore. This idea came from a quote by the Roman comedian Terence (around 195/185 – around 159 BC). It became a popular saying: Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus ("without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus freezes"). This simply means that love needs food and wine to grow strong. Art based on this saying was popular from 1550 to 1630, especially in Northern Mannerism in Prague and the Low Countries, and by Rubens. Because he was linked to the grape harvest, Bacchus became the god of autumn. He and his followers were often shown in art representing the different seasons.

Worship and Festivals in Greece

The worship of Dionysus became well-established by the 600s BC. He might have been worshiped as early as 1500–1100 BC by Mycenaean Greeks. Signs of Dionysian-like worship have also been found in ancient Minoan Crete.

Dionysia Festivals

The Dionysia, Haloa, Ascolia, and Lenaia festivals were all dedicated to Dionysus. The Rural Dionysia (or Lesser Dionysia) was one of the oldest festivals for Dionysus. It started in Attica and likely celebrated the growing of grapevines. It was held during the winter month of Poseideon (around December or January). The Rural Dionysia involved a procession where people carried long loaves of bread, jars of water and wine, and other offerings. Young girls carried baskets. After the procession, there were drama performances and competitions.

The City Dionysia (or Greater Dionysia) took place in cities like Athens and Eleusis. Held three months after the Rural Dionysia, this larger festival was around the spring equinox in March or April. The procession for the City Dionysia was similar to the rural ones but much grander.

Bacchic Mysteries

The main religious group for Dionysus was known as the Bacchic or Dionysian Mysteries. We don't know exactly where this religion began.

The Bacchic mysteries were important for creating traditions for big changes in people's lives. This was often shown by meeting gods who rule over death and change, like Hades and Persephone. Dionysus's mother Semele also played a role, likely linked to joining the mysteries.

The religion of Dionysus often included rituals where goats or bulls were sacrificed. Some participants and dancers wore wooden masks linked to the god.

As early as the 400s BC, Dionysus was linked to Iacchus. Iacchus was a smaller god from the Eleusinian Mysteries. This connection might have happened because the names Iacchus and Bacchus sounded similar.

Images for kids

-

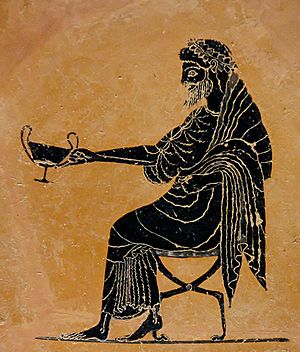

Dionysus extending a drinking cup (kantharos) (late sixth century BC)

-

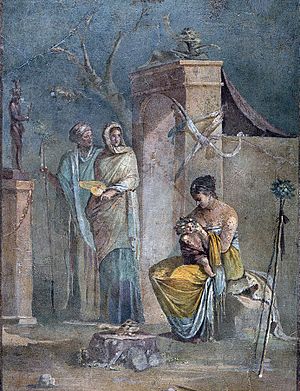

A Roman fresco depicting Bacchus with red hair, Boscoreale, c. 30 BC

-

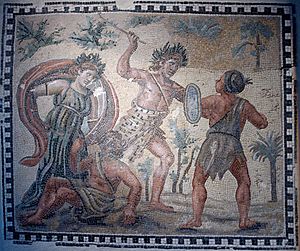

The Conquest of India by Dionysus at the archaeological museum of Sétif, ca. 200–300 CE

-

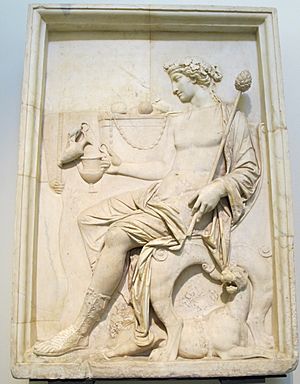

Roman marble relief (first century AD) from Naukratis showing the Greek god Dionysus, snake-bodied and wearing an Egyptian crown.

-

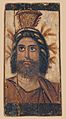

Painted wood panel depicting Serapis, who was considered the same god as Osiris, Hades, and Dionysus in Late Antiquity. Second century AD.

-

Bronze hand used in the worship of Sabazios (British Museum). Roman first–second century AD. Hands decorated with religious symbols were designed to stand in sanctuaries or, like this one, were attached to poles for processional use.

-

Birth of Dionysus, on a small sarcophagus that may have been made for a child (Walters Art Museum)

-

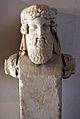

Marble bust of youthful Dionysus. Knossos, second century AD. Archaeology museum of Heraklion.

-

Wall protome of a bearded Dionysus. Boeotia, early fourth century BC.

-

Badakshan patera, "Triumph of Bacchus" (first–fourth century). British Museum.

-

North African Roman mosaic: Panther-Dionysus scatters the pirates, who are changed to dolphins, except for Acoetes, the helmsman; second century AD (Bardo National Museum)

-

Hanging with Dionysian Figures from Antinoöpolis, fifth–seventh century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Bacchus - Simeon Solomon (1867)

-

The Dionysus Cup, a sixth-century BC kylix with Dionysus sailing with the pirates he transformed to dolphins

-

Bronze head of Dionysus (50 BC – 50 AD) in the British Museum

-

Statue of Dionysus in Remich Luxembourg

-

Terracotta vase in the shape of Dionysus' head (circa 410 BC) – on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus

-

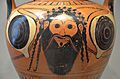

Amphora with cult mask of Dionysus, by the Antimenes Painter, around 520 BC, Altes Museum

-

Cult mask of Dionysus from Boeotia, fourth century BC

-

Marble statuette of Dionysos, early third century B.C, Metropolitan Museum

-

The Infant Bacchus, painting (c. 1505–1510) by Giovanni Bellini

-

Badakshan patera, "Triumph of Bacchus" (first–fourth century). British Museum.

-

A Hellenistic Greek mosaic depicting the god Dionysos as a winged daimon riding on a tiger, from the House of Dionysos at Delos (which was once controlled by Athens) in the South Aegean region of Greece, late second century BC, Archaeological Museum of Delos

-

North African Roman mosaic: Panther-Dionysus scatters the pirates, who are changed to dolphins, except for Acoetes, the helmsman; second century AD (Bardo National Museum)

-

Hanging with Dionysian Figures from Antinoöpolis, fifth–seventh century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Bacchus - Simeon Solomon (1867)

See also

In Spanish: Dioniso para niños

In Spanish: Dioniso para niños