Guyana–Venezuela territorial dispute facts for kids

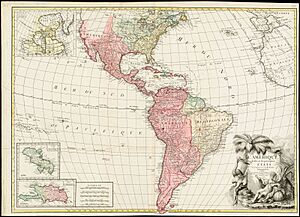

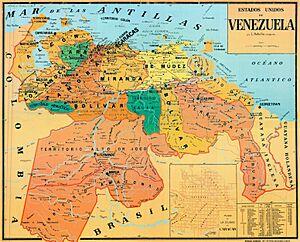

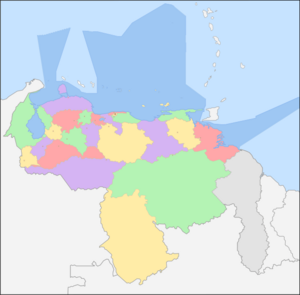

The Guyana–Venezuela territorial dispute is a disagreement between Guyana and Venezuela. They are arguing over a large area of land called the Essequibo region. This area is also known as Esequibo or Guayana Esequiba in Spanish. It covers about 159,500 square kilometers (61,600 sq mi) and is located west of the Essequibo River.

Currently, Guyana controls this territory. It is part of six of Guyana's regions. However, Venezuela claims it as its own, calling it the Guayana Esequiba State. This border argument started a long time ago. It began with the countries that used to rule these lands: Spain (for Venezuela) and the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (for Guyana). The dispute continued even after Venezuela and Guyana became independent.

In 1835, the British government asked an explorer named Robert Hermann Schomburgk to map the borders of British Guiana. He drew a line, which became known as the "Schomburgk Line". Both Venezuela and Britain disagreed with parts of this line. Tensions grew when gold was found in the region in 1876. This led to Venezuela stopping diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom in 1887.

The United States then represented Venezuela in talks with the United Kingdom. In 1899, a group of judges made a decision called the Paris Arbitral Award. This ruling mostly favored Britain. Later, in 1949, a secret note from one of the judges, Severo Mallet-Prevost, was published. It suggested that the 1899 decision was unfair and influenced by politics. This led Venezuela to complain to the United Nations in 1962. As a result, the Geneva Agreement was signed in 1966.

The Geneva Agreement says that the countries must find a "practical, peaceful, and satisfactory solution" to the dispute. If they cannot agree, the matter goes to an "appropriate international organ" or the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The Secretary-General sent the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In December 2020, the ICJ agreed to hear the case. In December 2023, Venezuela held a referendum where its people voted on whether the region should become a Venezuelan state. Venezuela said the vote showed strong support, but no vote happened in the disputed area itself.

Today, Venezuela claims all the land west of the Essequibo River. They call it Zona en Reclamación (Zone in Reclamation). In March 2024, Venezuela passed a law to make Essequibo a new state, governed from Tumeremo. This law is now being checked by their Supreme Court.

Contents

People in the Essequibo Region

In 2023, about 125,000 people lived in the Essequibo region. This is about 15.8% of Guyana's total population.

Early History of the Region

Before Europeans arrived, the the Guianas were home to many native groups. The Warao people are thought to be the first people in Guyana. Later, the Arawak and Kalina people also lived there. These native tribes were related to those in the northern Amazon. Evidence suggests the Arawaks came from the Orinoco and Essequibo River Basins. They moved into the northern islands and were later joined by the more warlike Carib Indians.

Spain claimed this region based on a papal bull from Pope Alexander VI and the Treaty of Tordesillas. However, other European countries like the Dutch and English did not recognize this treaty. They continued to settle the area. Most indigenous peoples of the Americas also did not recognize these European claims.

First European Visits

The first Europeans to see the region were ships led by Juan de Esquivel in 1498. The region was named after him. In 1499, Amerigo Vespucci and Alonso de Ojeda explored the mouths of the Orinoco River. They are believed to be the first Europeans to explore the Essequibo.

In 1581, Dutch settlers from Zeeland set up a trading post on the Pomeroon River. They were colonizing the land west of the Essequibo. This settlement, the Pomeroon colony, became part of the Essequibo colony. It was an important trading spot for the Dutch. Later, control of the area was given to the British.

Dutch Presence in the 1500s

Dutch colonisation of the Guianas mainly happened between the mouths of the Orinoco River in the west and the Amazon River in the east. The Dutch were in the Guianas by the late 1500s. They were even present as far west as the Araya Peninsula in Venezuela, where they used salt pans. By the 1570s, the Dutch were trading in the Guianas. At that time, neither the Portuguese nor the Spanish had set up permanent settlements there. A Dutch fort was built in 1596 at the mouth of the Essequibo River. The Spanish destroyed it later that year.

In 1597, Dutch interest in the Guianas grew after Sir Walter Raleigh published The Discovery of Guiana. On December 3, 1597, a Dutch expedition left Brielle and explored the coasts between the Amazon and Orinoco rivers. Their report, written by A. Cabeljau, gave more realistic information about the region than Raleigh's. It showed how the Dutch had traveled the Orinoco and Caroní River. They discovered many rivers and new lands. Cabeljau wrote that they had good relations with the native people. By 1598, Dutch ships often visited Guiana to set up settlements.

Dutch Settlements in the 1600s

Another Dutch fort was built at the mouth of the Essequibo River in 1613. Native groups supported it, but the Spanish destroyed it in November 1613. In 1616, Dutch ship captain Aert Adriaenszoon Groenewegen built Fort Kyk-Over-Al. It was located about 32 kilometers (20 mi) down the Essequibo River. He married the daughter of a native chief and controlled the Dutch colony for almost fifty years until his death in 1664.

By 1637, the Spanish noted that the Dutch had many people in their settlements at Amacuro, Essequibo, and Berbice. They also reported that all the Aruacs and Caribs were allied with the Dutch. Later reports showed the Dutch building forts from the Amazon River to the Orinoco River. In 1639, the Spanish said the Dutch in Essequibo were protected by 10,000 to 12,000 Caribs who were their allies. Captain Groenewegen was known for keeping both the Spanish and Portuguese from settling in the area.

In 1648, Spain signed the Peace of Münster with the Dutch Republic. Spain recognized the Dutch Republic's independence and their small possessions east of the Essequibo River. These had been founded by the Dutch before Spain recognized them. However, after a few decades, the Dutch started to spread west of the Essequibo River, into the Spanish Guayana Province. Spanish authorities often fought and destroyed these new settlements.

Serious Dutch colonization west of the Essequibo began in the early 1650s. The Pomeroon colony was being set up between the Moruka River and Pomeroon River. Many of these settlers were Dutch-Brazilian Jews who had left Pernambuco. By 1673, Dutch settlements reached as far as the Barima River.

The 1700s and Border Claims

In 1732, the Swedes tried to settle between the Low Orinoco and the Barima River. But by 1737, Major Sergeant Carlos Francisco de Sucre y Pardo (grandfather of Antonio José de Sucre) drove them out. By 1745, the Dutch had several territories in the region. These included Essequibo, Demerara, Berbice, and Surinam. Dutch settlements were also built on the Cuyuni River, Caroní River, and Moruka River.

When Spain created the Captaincy General of Venezuela in 1777, the Essequibo River was again stated as the natural border. This was between Spanish land and the Dutch colony of Essequibo. In 1788, Spanish officials officially complained about Dutch expansion into their territory. They suggested a new border line.

Dutch slaves in Essequibo and Demerara saw the Orinoco River as the border between Spanish and Dutch Guiana. Slaves often tried to cross the Orinoco to find more freedom in Spanish Guiana.

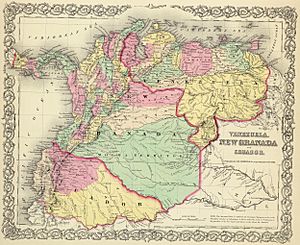

The 1800s: British Takeover and Disputes

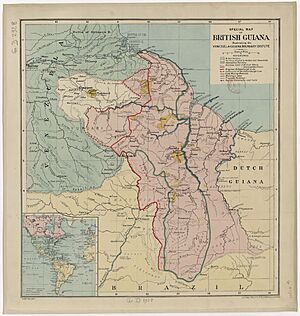

Under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, the Dutch colonies of Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo were given to the United Kingdom. By this time, the Dutch had defended the area from the British, French, and Spanish for almost 200 years. They often worked with native people who gave them information about Spanish attacks and escaped slaves. According to a scholar named Allan Brewer Carías, the 1814 treaty did not set a western border for what would become British Guiana. This is why explorer Robert Schomburgk was later asked to draw a border.

After Gran Colombia was formed in 1819, border arguments began between Gran Colombia (later Venezuela) and the British. In 1822, José Rafael Revenga, a Venezuelan official, complained to the British government. He said that British settlers in Demerara and Berbice had taken a large area of land west of the Essequibo River. He asked for these settlers to follow Venezuelan laws or move back to their old lands.

In 1824, Venezuela's new Ambassador to Britain, José Manuel Hurtado, officially claimed the Essequibo River as the border. Britain did not object at the time. However, the British government continued to encourage settlement west of the Essequibo River in the following years. In 1831, Britain combined the former Dutch territories into one colony, British Guiana.

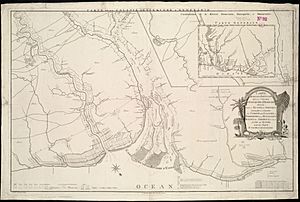

The Schomburgk Line

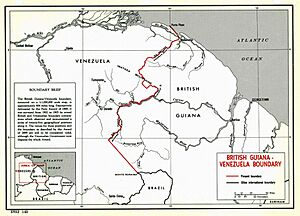

In 1835, a German explorer named Robert Hermann Schomburgk explored British Guiana. He drew a map showing what he believed was the western border claimed by the Dutch. In 1840, the British government asked him to officially survey the borders. This survey created the "Schomburgk Line". This line went far beyond where the British had settled. It gave British Guiana control of the mouth of the Orinoco River. Schomburgk himself said it did not include all the land Britain could claim.

Venezuela disagreed with Schomburgk's border markers at the Orinoco River. In 1844, Venezuela claimed all of Guiana west of the Essequibo River. In 1850, Britain and Venezuela agreed not to settle the disputed territory. But they did not define where this territory began or ended. Schomburgk's first map was published in 1840. Later, US President Grover Cleveland accused Britain of extending the line "in some mysterious way."

Gold is Discovered

The border dispute was quiet for many years until gold was found in the region. This discovery caused problems between the United Kingdom and Venezuela. In 1876, gold mines were set up in the Cuyuni basin. This area was Venezuelan territory beyond the Schomburgk line. Venezuela again claimed the border was at the Essequibo River. Britain responded with a counterclaim that included the entire Cuyuni basin.

In February 1887, Venezuela broke off diplomatic relations with Britain. In 1894, Venezuela asked the United States to help. The US suggested arbitration.

The Venezuela Crisis of 1895

The long-standing dispute became a major diplomatic problem in 1895. Venezuela hired William Lindsay Scruggs to represent them in Washington, D.C.. Scruggs argued that Britain's actions went against the Monroe Doctrine. This doctrine said that European powers should not interfere in the Americas. US President Grover Cleveland agreed.

British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and Ambassador Lord Pauncefote did not realize how important this dispute was to the US. The main issue was Britain's refusal to include the territory east of the Schomburgk Line in the arbitration. Eventually, Britain gave in and accepted the US's right to get involved. This forced Britain to agree to arbitration for the entire disputed territory.

The Treaty of Washington and Arbitration

The Treaty of Arbitration between the UK and Venezuela was signed in Washington on February 2, 1897. This treaty set up the rules for the arbitration. Its first article said: "An Arbitral Tribunal shall be immediately appointed to determine the boundary-line between the Colony of British Guiana and the United States of Venezuela."

The treaty also said that the judges would look into the lands that belonged to the Dutch or Spanish when Britain got British Guiana. They would then decide the border. Both Britain and Venezuela agreed that the arbitral ruling in Paris would be a "full, perfect, and final settlement" to the border dispute.

Venezuela argued that Spain, whose territory they had inherited, controlled land from the Orinoco River to the Amazon River. They said Spain only gave the Dutch a small amount of land within the disputed area. Britain, on the other hand, argued that the disputed Guiana region was not Spanish. They said it was too far away and not controlled by Spain. They also claimed that the native people had shared the land with the Dutch, not the Spanish.

Five judges heard the claims: two from Britain, two from the US (representing Venezuela), and one from Russia. The US represented Venezuela because Venezuela had broken off relations with Britain. Venezuela repeated its claim to the area west of the Essequibo. They said the border should run from the mouth of the Moruka River south to the Cuyuni River, then along the east bank of the Essequibo to the Brazilian border.

On October 3, 1899, the Tribunal mostly ruled in favor of Britain. The Schomburgk Line became the border, with two small changes. Venezuela received Barima Point at the mouth of the Orinoco. This gave them full control of the river. The second change moved the border to the Wenamu River instead of the Cuyuni River. This gave Venezuela a good amount of land east of the line. However, Britain received most of the disputed territory and all the gold mines.

Venezuelan representatives protested the outcome. They claimed that Britain had unfairly influenced the Russian judge.

After the 1899 Ruling

Right after the 1899 ruling, Venezuela's lawyers and officials expressed their disapproval. They said the award gave Venezuela Point Barima and a strip of land, giving them control of the Orinoco River. They also noted that 3,000 square miles in the interior were given to Venezuela. They felt that Britain's claims from 1895 were proven wrong. However, they also pointed out that Britain got almost all of its extreme claims, including valuable plantations and gold fields.

The Venezuelan government quickly showed its unhappiness with the 1899 Arbitral Award. On October 7, 1899, Venezuela's Foreign Minister, José Andrade, said the award was unfair and should not be followed. A mixed British-Venezuelan Boundary Commission began work in 1900 to mark the border. Venezuelan and British surveyors signed off on the border in 1905.

The 1900s: Renewed Dispute

After many diplomatic efforts failed, Venezuela complained about the 1899 award to the United Nations in 1945. This was four years before Guyana became independent from Britain.

In 1949, a US lawyer named Otto Schoenrich gave the Venezuelan government a secret note. It was written by Mallet-Prevost in 1944 and was only to be published after his death. Mallet-Prevost believed there was a political deal between Russia and Britain. He said the Russian judge, Friedrich Martens, had met with the two British judges before the ruling. Martens then offered the American judges a choice: accept a unanimous decision like the one made, or a 3-2 decision that would be even more favorable to the British. The alternative would have given the mouth of the Orinoco to the British. Mallet-Prevost said the American judges were upset but went along with Martens to avoid Venezuela losing even more land. This note gave Venezuela more reasons to claim the 1899 ruling was unfair.

By the 1950s, Venezuelan media pushed for the country to get the Essequibo region. Under the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, Venezuela planned to invade the Essequibo. But he was overthrown in 1958 before this could happen.

Complaint to the United Nations

Venezuela formally brought the issue up again at the United Nations in 1962. On November 12, 1962, Venezuelan foreign minister Marcos Falcón Briceño spoke to the United Nations General Assembly. He said the 1899 Paris Tribunal Arbitration was unfair and invalid. He argued that the British government and the judges acted wrongly. These complaints led to the 1966 Geneva Agreement.

The Geneva Agreement

On February 17, 1966, the governments of British Guiana, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela signed the "Agreement to resolve the controversy over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana." This is known as the Geneva Agreement of 1966. The agreement set up rules for the parties to solve the problem. A Mixed Commission was created to find solutions. However, the parties never agreed because they had different ideas about the agreement:

- Guyana said Venezuela had to prove the 1899 award was invalid before negotiations could start. Guyana did not accept that the 1899 decision was wrong.

- Venezuela said the Commission was for making a deal, not for legal arguments. They believed the 1899 award was implicitly invalid, otherwise the 1966 agreement would make no sense.

The Geneva Agreement also stated that any actions in the disputed territories while the agreement is in force "shall not be used to support or deny a claim to territorial sovereignty." It also said that both nations could only discuss the issue through official government channels.

When Guyana became independent on May 26, 1966, Venezuela recognized its territory east of the Essequibo River. But Venezuela clearly stated that it kept its claim over all the land west of the Essequibo River.

Venezuelan Occupation of Ankoko Island

Five months after Guyana became independent, Venezuelan troops took over Ankoko island in October 1966. They quickly built military bases and an airstrip. Guyana's Prime Minister, Forbes Burnham, protested and demanded the troops leave.

Venezuelan minister Ignacio Iribarren Borges replied that Ankoko Island was entirely Venezuelan territory and Venezuela had always owned it. The island remains under Venezuelan control, with an airport and military base.

The Rupununi Uprising

The rebellion was led by ranch owners in the Rupununi district. They feared the new Guyanese government would take away their land rights. Venezuela reportedly supported and armed these rebels.

Rebels attacked Lethem on January 2, 1969, using machine guns and bazookas. They locked citizens in their homes and blocked airfields. News reached Georgetown, and the Guyana Defence Force (GDF) was sent. When Guyanese soldiers arrived, the rebels quickly fled, ending the uprising.

The Guyanese government accused Venezuela of helping the rebels, which Venezuela denied. Members of the failed uprising fled to Venezuela for protection. Valerie Hart, a rebel leader, and others were given Venezuelan citizenship. This was because Venezuela claimed they were born in the disputed Essequibo territory. On January 6, 1969, Hart was removed from her political party for being involved "with the rebellion and plot by a foreign power."

Guyana charged 57 people with murder. Some Amerindian leaders later met with Prime Minister Burnham to declare their loyalty to Guyana.

The Port of Spain Protocol

In 1970, after the Mixed Commission ended, Presidents Rafael Caldera (Venezuela) and Forbes Burnham (Guyana) signed the Port of Spain Protocol. This agreement put Venezuela's claim on hold for 12 years. It allowed both governments to work together and build understanding. The protocol was signed by the foreign ministers of Venezuela and Guyana, and the British High Commissioner.

The Parliament of Guyana voted for the agreement. However, many Venezuelan politicians criticized it. Since 1970, Venezuelan maps show the entire area from the eastern bank of the Essequibo, including river islands, as Venezuelan territory. Some maps call the western Essequibo region the "Zone in Reclamation."

During the Falklands War in 1982, Venezuela showed renewed interest in its claims. A high-level Brazilian general warned Venezuela not to act against Guyana. In 1983, when the Port of Spain Protocol ended, Venezuelan President Luis Herrera Campins decided not to extend it. This meant Venezuela's claim over the territory was active again. Since then, contacts between Venezuela and Guyana are guided by a UN Secretary General's representative. The current representative is Dag Nylander, appointed in 2017.

The 2000s: Recent Developments

Chávez's Time in Office

President Hugo Chávez reduced tensions with Guyana. In 2004, during a visit to Georgetown, he said he considered the dispute finished.

The 2006 changes to the Venezuelan flag included an eighth star. This star represented the old Guayana Province and was seen as a way for Chávez to leave his mark.

In September 2011, Guyana asked the United Nations to extend its continental shelf by another 150 nautical miles. Guyana said there were "no disputes in the region" related to this request. Venezuela objected, saying that Guyana's request included the disputed territory west of the Essequibo River. Venezuela also noted that Guyana consulted other neighbors but not Venezuela.

Oil Discovery in Guyana

On October 10, 2013, the Venezuelan Navy stopped an oil exploration ship working for Guyana. The ship and its crew were taken to Margarita Island in Venezuela. Guyana said the ship was in Guyanese waters. Venezuela said the ship was in Venezuelan waters without permission. The ship, Teknik Perdana, was released a week later.

Despite Venezuela's protests, Guyana gave the American oil company ExxonMobil a license to drill for oil in the disputed sea area in early 2016. In May, Guyana announced that ExxonMobil had found promising oil results. Venezuela responded with a decree on May 27, 2015. This decree included the disputed maritime area in its national marine protection zone. This increased tensions, and Guyana took away the operating license of Conviasa, Venezuela's national airline.

On January 7, 2021, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro issued Decree No. 4415. This decree aims to strengthen Venezuela's claim to Guyana's Essequibo Region and its sea space.

The International Court of Justice

By December 2017, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres decided to send the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This was because there was no "significant progress" in resolving the dispute. In January 2018, Guterres concluded that the talks had not led to a peaceful solution. He chose to have the ICJ decide if the 1899 award was valid.

On March 29, Guyana asked the ICJ to solve the dispute. Venezuela suggested that Guyana restart diplomatic talks. Venezuela argued that Guterres had "exceeded his powers" and that the decision went against the Geneva Agreement. Venezuela also said it did not recognize the Court's authority as mandatory.

On June 19, Guyana announced it would ask the Court to rule in its favor. In July 2018, Venezuela, led by Nicolás Maduro, argued that the ICJ did not have authority over the dispute. Venezuela said it would not take part in the proceedings. The Court set deadlines for Guyana and Venezuela to present their arguments. During the Venezuelan presidential crisis, the opposition also supported the claim over the territory.

Oral hearings were planned for March 2020 but were delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Venezuela did not participate in the rescheduled hearings on June 30. On December 18, 2020, the Court ruled that it had authority and accepted the case. On March 8, 2021, Venezuela was given until March 8, 2023, to submit its counter-arguments.

On September 18, 2020, the United States announced it would join Guyana on sea patrols in the area. In September 2021, the Maduro government and the Venezuelan opposition agreed to work together on the claim over Essequibo. The ICJ ruled that it had authority to decide the dispute in April 2023.

Venezuelan Referendum in 2023

On October 31, 2023, the government of Guyana asked the ICJ to intervene against a proposed referendum in Venezuela. Guyana argued that the referendum was a way for Venezuela to stop negotiations. The Commonwealth of Nations and Caribbean Community (CARICOM) both condemned the referendum. They supported Guyana and the ICJ process.

Because of the increased tensions, the Brazilian military "intensified defensive actions" along its northern border on November 29, 2023. On December 1, 2023, the ICJ ordered Venezuela not to disrupt the territory currently controlled by Guyana until the court makes a final decision. The referendum took place on December 3. Venezuela's National Electoral Council reported that over 95% of Venezuelans voted "yes" on each of the five questions. However, international experts and media reported that voter turnout was very low and that Venezuela's government might have changed the results.

No similar vote has been held with the native people of the region by either Venezuela or Guyana.

Venezuelan Laws and Claims

Some Venezuelan laws say that Guayana Esequiba is part of the states of Bolívar and Delta Amacuro. The state of Bolívar's constitution says that its territory includes what historically belonged to the Guayana Province. It also states that the Paris Arbitral Award of 1899 is "void and null."

The state of Delta Amacuro's website says that it lost 23,467 square kilometers (9,061 sq mi) of its territory due to the 1899 award.

In Venezuela, the national government usually handles the Essequibo case. Local governors and mayors have little say. Maps of Venezuela must include the claimed area. This has led some people to wrongly think that Guayana Esequiba is a new Venezuelan state.

In 1999, Venezuela's new constitution stated that its territory includes what belonged to the Captaincy General of Venezuela before 1810. It also includes changes from treaties and arbitration awards that are not invalid.

In August 2015, some Venezuelan lawmakers suggested creating a 25th state called "Estado Esequibo." This would combine the Guayana Esequiba territory (159,500 square kilometers) with the Sifontes Municipality (24,393 square kilometers). Its capital would be Tumeremo. This proposal was not approved.

|

See Also

- Belizean–Guatemalan territorial dispute

- Borders of Venezuela

- Essequibo (colony)

- Gran Colombia

- Guayana Region

- Guyana–Venezuela relations

- South American territorial disputes

- Tigri Area, another territorial dispute involving Suriname

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |