History of Baton Rouge, Louisiana facts for kids

Baton Rouge, Louisiana started as a settlement in 1721. It was built near a "red stick" boundary marker used by the Muscogee people. Later, in 1849, it became the capital city of Louisiana.

Contents

Ancient Times

People have lived in the Baton Rouge area for a very long time, since about 8000 BC. We know this from things found near the Mississippi, Comite, and Amite rivers. Ancient people, who were hunter-gatherers, built large earth mounds here. This happened around 4000 BC. Around 1000 BC, the languages of the early Muskogean people started to split into different ones. By 800 AD, these groups were part of the Mississippian culture. When the Spanish first explored the area in the early 1500s, many of these native towns were already becoming smaller or were empty. The region had many small native groups and villages.

Colonial Period

French Rule (1699-1763)

In 1699, French explorer Sieur d'Iberville explored the Mississippi River. His group saw a red pole that marked the border between the hunting lands of the Houma and Bayogoula tribes. The French called this place le bâton rouge, which means "the red pole." This was a translation of a native word, Istrouma, which might have come from the Choctaw words iti humma, meaning "red pole." A carpenter named André-Joseph Pénicaut, who was with d'Iberville, wrote about the trip in 1723. He said the red stick marked the land between the Bayogoula and Oumas tribes. The red pole was likely at Scott's Bluff, where Southern University is today. It was said to be a 30-foot-tall painted pole decorated with fish bones. Europeans began settling Baton Rouge in 1721 when the French built a military post. In 1755, many French-speaking settlers from Canada, called Acadians, were forced to leave their homes by the British. Many of them moved to rural Louisiana. These people are now known as Cajuns, and they have kept their unique culture.

British Rule (1763-1779)

On February 10, 1763, the Treaty of Paris was signed. This happened after France lost the Seven Years' War to Great Britain. France gave its land in North America to Britain and Spain. Britain got all French lands east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans. During this time, about 11,000 Acadians were forced out of eastern Canada by British officers. Many were sent to France and later moved to southern Louisiana (New Spain). They settled in an area west and south of Baton Rouge, which became known as Acadiana. The first group of Acadian settlers arrived in 1765. At this time, the Mississippi River was the border between Spanish land (including Acadiana) and British land (including Baton Rouge). These settlers eventually called themselves Cajuns. They kept their own culture, including their clothing, music, food, and Catholic faith. Today, their descendants are an important part of Baton Rouge's culture. Baton Rouge became part of the new British province of West Florida. It was important because it was the southwestern edge of British North America. Spain ruled New Orleans and all the former French lands west of the Mississippi River. Baton Rouge slowly grew under British rule. The British leaders, based in Pensacola, gave out land and attracted European-American settlers. When the older British colonies on the Atlantic coast started to rebel in 1775, West Florida stayed loyal to the British Crown.

In 1778, during the American Revolutionary War, France declared war on Britain. Spain joined them in 1779. That year, the Spanish Governor Don Bernardo de Gálvez led nearly 1,400 soldiers from New Orleans toward Baton Rouge. They won battles at Fort Bute and on Lake Pontchartrain. Then, they captured Fort New Richmond in the Battle of Baton Rouge. Spanish officials renamed the site Fort San Carlos and took control of Baton Rouge. The British also gave up Fort Panmure (which became Natchez, Mississippi) and Fort New Richmond. Galvez later captured Mobile in 1780 and Pensacola in 1781, ending British control of the Gulf Coast. After the Revolutionary War, Great Britain gave West Florida to Spain.

Spanish Rule (1779-1810)

In the 1780s, a group of German farmers moved north from Bayou Manchac after floods. They settled south of Baton Rouge on high ground that protected them from the Mississippi River floods. They were called "Dutch Highlanders" (Dutch came from Deutsch, meaning German). Historic Highland Road, a main road in Baton Rouge today, was first a supply road for the indigo and cotton farms of these early settlers. German families like the Kleinpeters and Starings were very important in the area. Their descendants are still active in local businesses. In 1800, the Tessier-Lafayette buildings were built on what is now Lafayette Street, and they are still there today. In 1805, the Spanish leader Don Carlos Louis Boucher de Grand Pré planned the area known today as Spanish Town. In 1806, Elias Beauregard led the planning for what is now Beauregard Town.

Louisiana Statehood to Civil War

Republic of West Florida (1810-1812)

In 1803, the United States bought the former French territory in North America in the Louisiana Purchase. At this point, Spanish West Florida was almost completely surrounded by U.S. land. The Spanish fort at Baton Rouge became the only non-U.S. military post on the Mississippi River. Some people in West Florida started to plan a rebellion. One of them was Fulwar Skipwith, who was from Baton Rouge. A meeting was held in a house on a street now called Convention Street. On September 23, 1810, the rebels defeated the Spanish soldiers in Baton Rouge. They raised the flag of the new Republic of West Florida, called the Bonnie Blue Flag. This flag had a single white star on a blue background and later inspired the Texas flag. The West Florida Republic lasted for about 90 days, with St. Francisville as its capital. President James Madison saw this as a chance to add the territory to the United States. He ordered W. C. C. Claiborne to take control of the new republic. Madison said the land was always part of the U.S. because of the Louisiana Purchase. The rebels, who were mostly American settlers, did not fight Claiborne's forces. On December 10, 1810, the "Stars and Stripes" was raised. This meant that almost all the land that would become the state of Louisiana was now part of the U.S.

Early Statehood & Capital (1812-1860)

In 1812, Louisiana became a state. Baton Rouge was an important military spot. From 1819 to 1822, the U.S. Army built the Pentagon Barracks. This became a major command post during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor oversaw its construction and was its commander. In the 1830s, the "Old Arsenal" was built. This unique building was first used to store gunpowder for the U.S. Army. In 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette, a French hero of the American Revolution, visited Baton Rouge. The town celebrated him with a big dinner and dance. To honor him, the city changed the name of Second Street to Lafayette Street.

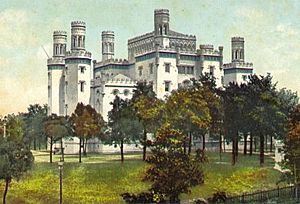

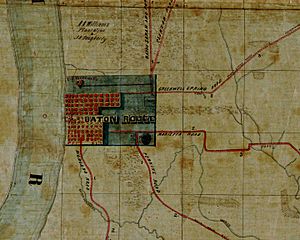

In 1849, the Louisiana state government in New Orleans decided to move the capital to Baton Rouge. Many lawmakers, especially wealthy farmers, worried that too much power was in New Orleans, the state's largest city. They also wanted to lessen the influence of French Creoles in politics. In 1840, New Orleans had over 102,000 people, making it the third-largest city in the U.S. Its economy was strong, partly due to the slave trade. Goods from the center of the country passed through New Orleans for export. In contrast, Baton Rouge had only 2,269 people in 1840. New York architect James Dakin designed the new capitol building in Baton Rouge. Instead of looking like the U.S. Capitol, he designed a medieval-style castle with turrets and crenellations, overlooking the Mississippi River. In 1859, the Capitol was praised in DeBow's Review, a famous magazine in the South. But the writer Mark Twain disliked it. In his book Life on the Mississippi (1874), he wrote that it was "pathetic" that such a castle was built in an "otherwise honorable place." Twain also wrote about the city: "Baton Rouge was covered in flowers, like a greenhouse. We were in the true South now. The magnolia trees in the Capitol grounds were beautiful and smelled wonderful, with their thick leaves and huge snowball blossoms.... We were definitely in the South at last; for here the sugar region begins, and the plantations—large green flat areas, with sugar mills and slave quarters grouped together in the distance—were in view." During the first half of the 1800s, the city grew steadily because of steamboat trade and transportation. By 1861, when the American Civil War began, the population had more than doubled to nearly 5,500 people. The Civil War stopped economic growth, but the city was not badly damaged until Union forces took it over in 1862.

Civil War (1860-1865)

Southern states left the Union mainly because of disagreements over slavery. South Carolina was the first state to leave in December 1860, and other states quickly followed. In January 1861, Louisiana voted to leave the Union, with 112 votes for and 17 against. Baton Rouge formed several volunteer groups for the Confederate army, including the Pelican Rifles and the Delta Rifles. About one-third of the town's men volunteered. The Confederates gave up Baton Rouge (which had 5,429 people in 1860) with little fighting, choosing to gather their forces elsewhere. In May 1862, Union troops entered the city and began their occupation. The Confederates tried only once to take Baton Rouge back. Even with help from a group called the Barbarians, they were outnumbered and outgunned. The Confederates lost the battle, and the town was badly damaged. However, Baton Rouge did not suffer as much destruction as other cities that were major battle sites during the Civil War. Many buildings from before the war are still standing. In 1886, a statue of a Confederate soldier was put up to honor those who fought in the Civil War. In the early 2000s, the statue was moved to make way for the new North Boulevard Town Square, which started construction in 2010. This was part of a plan to create a central area for events downtown. The statue will be placed on the grounds of the Old Capitol Building when the work is finished.

Reconstruction to Civil Rights Era

Reconstruction Era (1865-1900)

After the Civil War, many freed slaves moved to towns and cities in the South. This led to a big increase in Baton Rouge's black population. They left rural areas to escape white control and find jobs, education, and safety in their own communities. In 1860, black people (mostly slaves) made up almost one-third of the town's population. By 1880, Baton Rouge was 60 percent black. It wasn't until 1920 that the white population in Baton Rouge was more than 50 percent of the total. During the Reconstruction Era, state offices were in New Orleans, where U.S. troops were based. After 1868, elections often involved violence and cheating as white people tried to regain power and stop black people from voting. In 1874, thousands of White League members, a paramilitary group, took over state government buildings in New Orleans for several days. Black people continued to be elected to local offices. Before Reconstruction ended in 1877, white Democratic politicians regained control of the state and city governments. They used violence and threats from groups like the White League to stop black people from voting. By 1880, Baton Rouge was recovering from the war. The city's population reached 7,197. At the end of the 1800s, white Democrats in the state government passed laws that took away voting rights from black people, including educated Louisiana Creole people. They also passed laws for racial segregation and "Jim Crow," which treated African Americans as second-class citizens. This system lasted until the 1960s, when federal civil rights laws, like the Voting Rights Act of 1965, were passed to protect voting rights. However, this period of strict control by white Democrats was shorter in Baton Rouge. In the 1890s, a more modern type of leadership developed among whites in the city. More people cared about the city, and the arrival of the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway brought new businesses and led to better leadership.

Early to Mid 20th Century (1900-1953)

The city built new water systems, brought electricity to many homes and businesses, and spent money on public buildings, new schools (which were segregated by race), paved streets, and improved drainage and sewers. They also created a public health department. Because black people were not allowed to vote, their segregated schools and neighborhoods received less funding, even though they paid taxes. By the early 1900s, Baton Rouge became an industrial city because of its good location for oil, natural gas, and salt production. In 1909, the Standard Oil Company (now ExxonMobil) built a facility that attracted other chemical companies. Although the waterfront flooded in 1912, the city avoided major damage then and during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which caused a lot of damage in other areas.

In 1932, during the Great Depression, Governor Huey P. Long ordered the building of a new Louisiana State Capitol. This was a big public project and a sign of modernization. He also improved services for the people. The growth of the state government helped the city's businesses and services grow.

Around the same time, the Louisiana Institute for the Blind and the School for the Deaf and Dumb were built in Baton Rouge. During World War II, the military needed more production from local chemical plants, which helped the city grow and created many new jobs. In the late 1940s, Baton Rouge and East Baton Rouge Parish combined their governments, with a mayor/president in charge. It was one of the first cities in the U.S. to do this. The parish includes three other cities: Baker, Zachary, and Central.

Civil Rights Era (1953-1968)

In 1953, Baton Rouge was the site of the first bus boycott by African Americans in the civil rights movement. On June 20, 1953, black citizens of Baton Rouge started an organized boycott of the segregated city bus system. It lasted for eight days. Since black people made up 80% of the riders, the boycott greatly affected the city's income. They protested against being limited to certain seats and being forced to give up seats to white riders. This boycott became a model for the more famous Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. The boycott was led by the new United Defense League (UDL), directed by Willis Reed and Reverend T. J. Jemison. A volunteer "free ride" system, organized through black churches, helped African Americans get around. Because of the boycott, the Baton Rouge city council passed a new rule. It changed segregated seating so that black riders would fill seats from the back, and white riders would fill seats from the front. They made sure the races did not sit in the same rows. Many historians believe the boycott's success in getting fair treatment for black bus riders paved the way for larger civil rights efforts. The boycott was celebrated on its 50th anniversary in June 2003. The student sit-ins that began in Greensboro, NC on February 1, 1960, reached Baton Rouge on March 28. Seven Southern University (SU) students were arrested for sitting at a Kress lunch counter to get service. Public education was still segregated, and SU was a historically black college. The next day, nine more students were arrested for sitting in at the Greyhound bus station. The day after that, Major Johns, an SU student and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) member, led over 3,000 students in a march to the state capitol to protest segregation and the arrests. Major Johns and the 16 students arrested were expelled from SU and banned from all public colleges in the state, which threatened their education. SU students organized a class boycott to get the expelled students back. Many parents took their children out of the college, fearing for their safety. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the students' arrests. In 2004, Southern University gave them honorary degrees, and the state government honored them with a resolution. In October 1961, SU students Ronnie Moore, Weldon Rougeau, and Patricia Tate restarted the Baton Rouge CORE chapter. After talks with downtown stores failed to end segregation, they called for a boycott in early December, at the start of the busy holiday shopping season. Fourteen CORE protesters were arrested in mid-December and held in jail for a month. Over 1,000 SU students marched to the state capitol on December 15 to protest. Police attacked them with dogs and tear gas, arresting more than 50 students. Thousands rallied on the SU campus against segregation. To stop more protests, SU leaders closed the campus four days early for Christmas break. In January 1962, U.S. Federal Judge Gordon West issued an order against CORE that banned all protests at SU. The university expelled many activist students, and state police occupied the campus to stop further protests. Judge West's order was finally overturned by a higher court in 1964. However, during those years, civil rights activities were largely stopped. In February 1962, Dion Diamond, a Freedom Rider and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, was arrested for entering the SU campus to meet with students. He was accused of "criminal anarchy"—trying to overthrow the government of Louisiana. SNCC Chairman Chuck McDew and white field secretary Bob Zellner were also arrested and charged with "criminal anarchy" when they visited Diamond in jail. Zellner was put in a cell with white prisoners, who attacked him as a "race-mixer" while the guards watched. After years of legal battles, the charges against Diamond were dropped, but he had to serve 60 days for other charges. In 1964 and 1965, federal civil rights laws were passed. These laws ended legal segregation and began to enforce African Americans' right to vote and serve on juries.

Recent History to Present

In the 1970s, Baton Rouge saw a big increase in the petrochemical industry. This caused the city to grow outwards from its original center, leading to modern suburban areas. However, in recent years, the government and businesses have started to move back to the downtown area. A building boom began in the 1990s and continues today, with many large projects improving the city and adding new buildings. At the start of the 2000s, Baton Rouge continued to grow steadily. It also became a technology leader among cities in the South. It was ranked No. 1 among America's most wired cities, even more wired than New Orleans. Baton Rouge added advanced traffic camera systems, a wide city-wide wireless internet network, and a modern cell phone network. The city's population grew steadily, reaching over 225,000 in the 2000 Census. This was more than similar cities like Mobile, Alabama, Montgomery, Alabama, and Corpus Christi, Texas. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Levees broke, flooding much of New Orleans and parts of lower Mississippi. Although Baton Rouge had minor damage, it lost power and services. The city also became a safe place for people from New Orleans. Baton Rouge served as a main center for federal and state emergency efforts in Louisiana. The city carried out huge rescue efforts as people from the New Orleans metropolitan area moved north after the disaster. LSU's basketball arena, the Pete Maravich Assembly Center, and the nearby LSU Field House were turned into emergency hospitals. Victims were flown in by helicopter and brought by buses to be treated. They were checked, and depending on their condition, were treated there or sent further west to Lafayette, Louisiana. By late 2005, about 200,000 displaced people had moved to Baton Rouge. As a result, by August 31, TV station WAFB reported that the city's population had more than doubled, from about 228,000 to at least 450,000. East Baton Rouge Parish's population grew to almost 600,000 after the forced evacuation. Since then, city planning efforts have led to many completed and planned improvements to the city's infrastructure.

By the end of the 2000s, Baton Rouge was one of the largest mid-sized business cities in the United States. It is also one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas with a population under 1 million. It had 633,261 residents in 2000 and an estimated 750,000 in 2008. Baton Rouge's city population grew rapidly after Hurricane Katrina as people from the New Orleans area moved north. Most of them later returned to their original cities. Because hurricane victims returned home and native Baton Rouge residents moved to nearby parishes like Livingston and Ascension, the U.S. Census Bureau in its 2007-2008 estimate said Baton Rouge was the second-fastest city in declining population. Baton Rouge has created a Downtown Development District and started a process of urban growth and renewal to focus on attractions downtown. North Boulevard Town Square, for example, built near the Old Capitol Building, provides a place for city events and reconnects the city to the river.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |