History of Lviv facts for kids

Lviv is a very old city in western Ukraine. It has been a settlement for over 1,000 years and a city for more than 700 years! Before Ukraine became a modern country, Lviv was part of many different states and empires.

It was known as Lwów when it was part of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was called Lemberg when it belonged to the Austrian Empire and later Austria-Hungary. After World War I, it was briefly part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic, then Poland again, and finally the Soviet Union. Even the Swedes and Ottoman Turks tried to conquer Lviv, but they didn't succeed.

Contents

Early History of Lviv

Scientists have found signs that people lived in the Lviv area as far back as the 5th century. They found an old fort, called a gord, on Chernecha Hora Street. It is believed to have been built by the White Croats.

In 981, the Cherven Cities, including the Lviv area, were taken over by Volodymyr the Great. They became part of Kyivan Rus'. Later, in 1031, Yaroslav the Wise, another prince of Kyiv, took control.

Founding of Lviv

Lviv was officially started in 1256 by King Daniel of Galicia. He named the city after his son, Lev. The name Lviv means "Leo's lands" or "Leo's City." This is why its Latin name is Leopolis.

In 1261, the city was attacked by the Tatars. Some stories say the city was completely destroyed, while others say only the castle was ruined. Everyone agrees that the Mongol general Burundai gave the order. He told the local ruler, "If you want peace with me, then destroy all your castles."

After King Daniel died, his son Lev rebuilt Lviv around 1270. Lev made Lviv the capital of Galicia-Volhynia. The city quickly grew because it was a major trading center. Many German, Armenian, and other merchants came to live there. Lots of Polish people also moved to Lviv from Kraków, Poland, after a big famine. By 1280, many Armenians lived in Lviv and even had their own Archbishop.

Changes in Power

In 1323, the local ruling family, the Romanovich dynasty, ended. The city was then inherited by Boleslaus of Masovia. He became a ruler and changed his name to "Yuriy." He also converted to Eastern Orthodoxy. However, the local nobles didn't support him, and he was eventually poisoned.

In 1340, the city was taken over by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was ruled by a voivode (a type of governor) named Dmytro Dedko. He was a favorite of the Lithuanian prince Lubart.

Wars and Polish Rule

After Boleslaus Yuriy died in 1340, King Casimir III of Poland claimed the city. The local nobles chose Dmytro Dedko as their ruler and fought off a Polish invasion. King Casimir III tried to conquer Lviv in 1340 and burned down the old princely castle.

After Dedko died, King Casimir III finally took Lviv and the region of Red Ruthenia in 1349. Casimir built two new castles. From then on, the people of Lviv were encouraged to become more Polish and Catholic.

In 1356, Casimir III gave Lviv Magdeburg rights. This meant that wealthy citizens could elect a city council to manage city issues. The city council's seal from the 14th century said Civitatis Lembvrgensis. This led to fast growth for the city. The Latin Cathedral was built, and a church was built where today's St. George's Cathedral stands. The new self-government also helped the Armenian community grow, and they built their Armenian Cathedral in 1363.

After Casimir died in 1370, his nephew, King Louis I of Hungary, took over. In 1372, he put Lviv under the control of his relative Władysław. When Władysław left in 1387, the Hungarians occupied Galicia-Volhynia. But soon, Jadwiga, the ruler of Poland, took it over and made it part of the Polish Crown.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

When Lviv was part of Poland (and later the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), it was known as Lwów. It became the capital of the Ruthenian Voivodeship, a large region. The city was given the right to charge fees for goods passing through it. This meant Lwów made a lot of money from trade between the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea.

In the centuries that followed, Lwów's population grew quickly. It became a city with many different ethnic groups and religions. It was also an important center for culture, science, and trade. The city's defenses were made stronger, making Lviv one of the most important fortresses protecting the Commonwealth from the southeast.

Lwów had three important religious leaders: a Roman Catholic archbishop, a Greek Catholic archbishop, and an Armenian Catholic archbishop. Many different groups lived in the city, including Germans, Jews, Italians, Englishmen, and Scotsmen. By the 16th century, there were also strong Protestant communities. By the early 1600s, the city had about 25,000 to 30,000 people. Around 30 craft organizations were active, covering over a hundred different skills.

Challenges for the Commonwealth

In the 17th century, Lviv was attacked many times but was never captured. This led to its motto, Semper fidelis, which means "Always faithful." In 1649, Bohdan Khmelnytsky and his Cossacks attacked the city and destroyed the local castle. However, the Cossacks didn't stay and left after receiving a payment.

In 1655, the Swedish armies invaded Poland. They tried to capture Lviv but had to leave before they could. The next year, armies from Transylvania attacked Lviv, but the city was not taken. In 1672, the Ottoman army attacked Lviv again. But the war ended before the city was captured. In 1675, the Ottomans and Tatars attacked, but King John III Sobieski defeated them in the Battle of Lwów.

However, in 1704, during the Great Northern War, the city was captured and looted for the first time by the armies of Charles XII of Sweden.

Habsburg Era

18th Century Changes

In 1772, after the First Partition of Poland, Lviv became part of Austria. It was renamed Lemberg (its German name) and became the capital of the Austrian province called the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. At first, Austrian rule was quite open. In 1773, Lviv's first newspaper, Gazette de Leopoli, began to be published.

The city grew a lot during the 19th century. Its population increased from about 30,000 in 1772 to 196,000 by 1910. This fast growth also led to more poverty in the region.

In 1784, Emperor Joseph II reopened the University of Lviv. Most classes were taught in Latin. Some classes, like Pastoral Theology, were in Polish. German was also used in some courses, especially in Medicine. The university even created a special institute in 1787 for Greek Catholic students.

Wojciech Bogusławski opened the first public theater in Lviv in 1794. Józef Maksymilian Ossoliński started the Ossolineum in 1817, which was a scientific institute. In the early 1800s, Lviv also became the main center for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Early 19th Century Developments

In the 19th century, the Austrian government tried to make the city's education and government more German. The university was closed in 1805 and reopened in 1817 as a German-only academy. Many other social and cultural groups were also banned. A lot of German-speaking people moved to Lviv, making the city feel very German by the 1840s. This created some tension between the new German leaders and the older Polish leaders.

The 1848 Revolution

The strict rules from the Habsburg Austrian Empire led to protests in 1848. People sent a request to Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria. They asked for local self-government, education in Polish and Ukrainian, and for Polish to be an official language. National Guard groups were formed, some Polish and some Ukrainian. However, the Polish revolutionaries soon made the Ukrainian groups join them, which caused problems between the two groups.

After an uprising in Vienna was stopped, unrest spread to Lviv. Arguments broke out between the National Guard and Austrian soldiers. On November 6, 1848, the Austrian Army started bombing the city center for three hours. The town hall, academy, library, museum, and many houses caught fire. A group of important citizens surrendered to the general that day. The city was put under strict control, and all houses could be searched.

Mid-19th Century Progress

After the 1848 revolution, Ukrainian and Polish languages were brought back to the university. Around this time, a special way of speaking Polish, called the Lwów dialect, developed in the city. It included words from many other languages.

Most of the requests from the 1848 revolution were granted in 1861. A Galician parliament (Sejm Krajowy) was opened. In 1867, Galicia gained a lot of freedom in its culture and economy. The university was also allowed to teach in Polish again.

In 1853, Lviv became the first European city to have street lights! This was thanks to innovations by Lviv residents Ignacy Łukasiewicz and Jan Zeh. They introduced kerosene lamps as street lights. These were updated to gas lights in 1858 and then to electricity in 1900.

After 1867, the Austrian Empire became Austria-Hungary. Austrian rule in Galicia slowly became more liberal. From 1873, Galicia was mostly an independent province of Austria-Hungary. Polish and, to a lesser extent, Ukrainian were official languages. Germanization (making things German) stopped, and censorship was lifted. The Galician Sejm (parliament) and local government in Lviv had many special rights, especially in education, culture, and local matters.

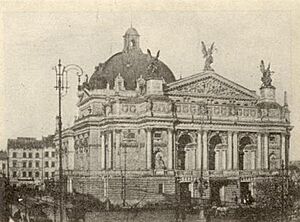

In 1894, the city hosted the General National Exhibition. Lviv grew very fast, becoming the 4th largest city in Austria-Hungary by 1910. Many beautiful public buildings and apartment houses were built during this time. Buildings from the Austrian period, like the opera theater, still make up much of the city center.

End of Habsburg Rule

During Habsburg rule, Lviv became a very important cultural center for Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish people. The city was a meeting place for these cultures. In 1910, according to an Austrian census, 51% of the city's people were Roman Catholics, 28% were Jews, and 19% belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. In terms of language, 86% spoke Polish, and 11% spoke Ukrainian.

Galicia was the only part of the former Polish state that had some cultural and political freedom. Lviv became a major Polish cultural center. It was home to the Polish Ossolineum (with a huge collection of Polish books), the Polish Academy of Arts, and the Polish Historical Society.

Lviv was also a key center for the Ukrainian patriotic movement and culture. Unlike other parts of Ukraine under Russian rule, where Ukrainian publications were banned, Lviv had many important Ukrainian institutions. These included the Prosvita society (for spreading Ukrainian literacy) and the Shevchenko Scientific Society. It was also the main seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Lviv was also a major center of Jewish culture, especially for the Yiddish language. It was home to the world's first Yiddish-language daily newspaper.

20th Century

During World War I, the city was captured by the Russian army in September 1914. After a short Russian occupation, Austria-Hungary took it back in June 1915. When the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of World War I, the local Ukrainian people declared Lviv the capital of the West Ukrainian People's Republic on November 1, 1918.

Polish–Ukrainian Conflict

As the Austro-Hungarian government fell apart, the Ukrainian National Council was formed in Lviv on October 18, 1918. This council wanted to unite the western Ukrainian lands into one state. While the Poles were also trying to take over Lviv, Ukrainian officers took control of the city during the night of October 31 – November 1. The West Ukrainian People's Republic was announced on November 1, 1918, with Lviv as its capital.

This announcement surprised the Poles, who were the majority in the city and considered the territory Polish. While Ukrainian residents were excited, the Polish residents were shocked. Ukrainian soldiers tried to arrest the Austrian governor, but he refused to formally hand over power. He eventually gave his authority to his Ukrainian deputy, who then gave it to Ukrainian leaders.

Immediately, the Polish majority in Lviv started an armed uprising. The Ukrainian soldiers, many of whom were young peasants unfamiliar with the city, could not stop it. The Poles soon took control of most of the city center. Ukrainian forces then surrounded the city, which was defended by Polish volunteers, including the Lwów Eaglets (young Polish defenders).

After an international group agreed to leave the city under Polish control, Polish regular forces arrived on November 19. By November 22, the Ukrainian troops were forced out. When the Polish forces captured the city, some Polish soldiers looted and burned parts of the Jewish and Ukrainian areas. After taking control, Polish authorities closed Ukrainian institutions and arrested many Ukrainians. Ukrainian members of the city council resigned in protest.

In the following months, Polish forces captured other parts of Galicia controlled by the West Ukrainian People's Republic. An agreement in April 1920 between Poland and Symon Petlura, the Ukrainian leader, recognized Poland's control of Lviv. This was in exchange for Polish military help against the Bolsheviks.

Polish–Soviet War

During the Polish–Soviet War of 1920, the city was attacked by the Red Army. In mid-June 1920, the Red Army tried to reach the city. Lviv prepared its defense. The people of Lviv formed three infantry regiments and two cavalry regiments and built defensive lines. The city was defended by Polish and Ukrainian forces.

After almost a month of heavy fighting, the Red Army crossed the Bug River on August 16 and began an attack on the city. The fighting was intense, with many casualties on both sides. But after three days, the attack was stopped, and the Red Army retreated. For its brave defense, the city was given the Virtuti Militari medal.

Between the World Wars

After the Peace of Riga, Lviv remained part of Poland. It became the capital of the Lwów Voivodeship. Lviv was the third-largest city in Poland and became a very important center for science, sports, and culture. For example, the Lwów School of Mathematics was famous for its mathematicians.

Population of Lwów, 1931 (by religion)

| Roman Catholic: | 157,500 | (50.4%) |

| Judaism: | 99,600 | (31.9%) |

| Greek Catholic: | 49,800 | (16.0%) |

| Protestant: | 3,600 | (1.2%) |

| Orthodox: | 1,100 | (0.4%) |

| Other denominations: | 600 | (0.2%) |

| Total: | 312,200 |

Source: 1931 Polish census

Population of Lwów, 1931 (by first language)

| Polish: | 198,200 | (63.5%) |

| Yiddish or Hebrew: | 75,300 | (24.1%) |

| Ukrainian or Ruthenian: | 35,100 | (11.2%) |

| German: | 2,500 | (0.8%) |

| Russian: | 500 | (0.2%) |

| Other denominations: | 600 | (0.2%) |

| Total: | 312,200 |

Source: 1931 Polish census

During this time, Lwów grew a lot, from 219,000 people in 1921 to 312,200 in 1931. By 1939, it had an estimated 318,000 residents. Even though Poles were the majority, Jews made up more than a quarter of the population. There was also a significant Ukrainian minority. Other groups like Germans and Armenians also lived there, adding to Lwów's diverse culture.

Lwów was the second most important cultural and academic center in Poland, after Warsaw. It had five higher education facilities, including a well-known university. Lwów also hosted the Targi Wschodnie (The Eastern Trade Fair) every year, which helped the city's economy grow.

At the same time, the Polish government reduced the rights of local Ukrainians. Many Ukrainian schools were closed or changed to be mostly Polish. More Polish people moved to the city, which reduced the percentage of Ukrainians. At the university, most Ukrainian departments were closed, and many Ukrainian professors were fired. This led to an underground university in Lwów. Polish authorities also started using the old word "Ruthenians" instead of "Ukrainians" in official documents, which many Ukrainians disliked.

The Polish government also wanted to highlight the city's Polish character. Unlike Austrian times, when all cultural groups had public celebrations, limits were placed on Jewish and Ukrainian public displays. Celebrations for the Polish defense of Lviv became a major Polish event. Military parades and memorials for battles against Ukrainians in 1918 became common. A large memorial for Polish soldiers from that conflict was built in the city's Lychakiv Cemetery. The Polish government promoted the idea of Lviv as a strong Polish outpost in the east.

World War II

Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. German troops reached Lviv's suburbs on September 12 and began to surround the city. The city's defenders were ordered to hold out at all costs. This was because Lviv's location was important for preventing the enemy from moving further. Polish troops from central Poland were also trying to reach the city to organize a defense. This led to a 10-day battle, known as the Battle of Lwów.

On September 19, a Polish attack failed. Then, Soviet troops (who had invaded Poland on September 17 as part of a secret agreement with Germany) replaced the Germans around the city. On September 21, the Polish commander officially surrendered to Soviet troops.

The Soviet and Nazi forces divided Poland between them. The Soviet-occupied eastern part of Poland, including Lviv, was absorbed into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. At first, some Jewish and Ukrainian people welcomed the Soviet takeover, believing it would protect the Ukrainian population. However, the Soviets immediately began to remove Polish influence. Many Poles and Jews from Lviv were sent eastward into the Soviet Union. About 30,000 were deported in early 1940 alone. Some Ukrainians were also deported.

When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Soviet secret police (NKVD) quickly executed prisoners in Lviv's jails. Around 8,000 people were killed.

Initially, many Ukrainians saw the German troops as liberators after two years of harsh Soviet rule. However, from the very beginning of the German occupation, the situation for the city's Jewish residents became terrible. After suffering deadly attacks, Jewish people were forced into a new ghetto. Most were then sent to German concentration camps or killed locally. Poles and some Ukrainians in the city also faced harsh policies, leading to many killings. Among the first to be murdered were professors from the city's universities and other Polish leaders.

On June 30, 1941, the first day of German occupation, a Ukrainian nationalist group declared the restoration of an independent Ukrainian state. This was done without German approval, and the organizers were arrested. The policy of the occupying power quickly became harsh towards Ukrainians as well. Some Ukrainian nationalists went underground and fought against the Nazis, Poles, and Soviet forces.

As the Red Army approached Lviv in 1944, the Polish Home Army ordered an armed uprising on July 21. After four days of fighting and the Red Army's advance, the city was handed over to the Soviet Union. Again, Soviet authorities quickly became hostile to the city's Poles, including members of the Polish Home Army.

Lviv and the Holocaust

Before the war, Lviv had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland. This number grew even more as war refugees arrived, reaching over 200,000 Jews. Immediately after the Germans entered the city, groups of soldiers and local helpers organized a massive pogrom (violent attack). They claimed it was revenge for earlier Soviet killings. During a four-week period in June and July 1941, nearly 4,000 Jews were murdered. On July 25, 1941, another pogrom occurred, and nearly 2,000 more Jews were killed.

The Lwów Ghetto was created after these attacks. It held about 120,000 Jews. Most of them were sent to the Belzec extermination camp or killed locally over the next two years. The terrible conditions in the ghetto and deportations to death camps, like the Janowska labor camp, led to the near complete destruction of the Jewish population. By the time Soviet forces returned in 1944, only 200–300 Jews remained.

Simon Wiesenthal (who later became a famous Nazi hunter) was one of the few Jews from Lviv to survive the war. Many city residents tried to help and hide Jews from the Nazis, even though it meant a death penalty if caught. For example, Leopold Socha helped two Jewish families survive in the sewers. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky also made a big effort to save Jewish people.

Post-War Soviet Period

After World War II, Lviv remained part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, despite Polish efforts to keep it. During the Yalta Conference, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin insisted on keeping the territory the Soviet Union had taken at the start of the war. Although U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted Poland to keep Lviv, they reluctantly agreed.

Most of the remaining Polish population was sent to new Polish territories that were gained from Germany. People from Ukrainian-speaking rural areas around Lviv, as well as from other parts of the Soviet Union, moved to the city. They were attracted by the city's fast-growing industries. This movement of people changed the city's traditional ethnic makeup, which had already been drastically altered by the displacement or murder of Polish, Jewish, and German populations.

The Soviet government had a general policy of Russification (making things more Russian) in post-war Ukraine. In Lviv, this included closing down the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. However, after Joseph Stalin died, Soviet cultural policies became more relaxed. This allowed Lviv, as a major center of Western Ukraine, to become an important hub for Ukrainian culture.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city grew significantly in both population and size. Many important factories were built or moved from other parts of the USSR, bringing workers with them. This also led to some Russification of the city. Some notable factories included the bus factory (Lvivsky Avtomobilny Zavod), which made most of the buses in the Soviet Union, and the TV factory Elektron, which made popular televisions. Most of these factories still exist today, though they face economic challenges.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, during a period of Soviet openness (called Glasnost and Perestroika), Lviv became the center of Rukh (People's Movement of Ukraine). This was a political movement that pushed for Ukraine's independence from the USSR.

Independent Ukraine

When the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Lviv became part of the newly independent Ukraine. It serves as the capital of the Lviv Oblast (a region). Today, Lviv remains one of the most important centers of Ukrainian culture, economy, and politics. It is known for its beautiful and varied architecture.

In its recent history, Lviv strongly supported Viktor Yushchenko during the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election. It played a key role in the Orange Revolution. Hundreds of thousands of people gathered in freezing temperatures to protest for the "Orange" side. Acts of civil disobedience forced the local police chief to resign, and the local assembly refused to accept the unfair election results.

Lviv celebrated its 750th anniversary in September 2006. A big event was a light show around the Lviv Opera House.

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lviv has been hit by Russian missile and aerial attacks. Military and infrastructure targets have been attacked, and sadly, there have been civilian casualties and damage to residential buildings.

See also

- Timeline of Lviv

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |