History of U.S. foreign policy, 1913–1933 facts for kids

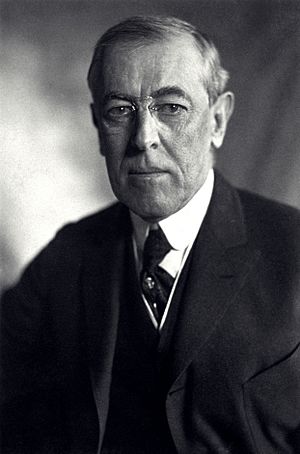

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1913–1933 tells the story of how the United States dealt with other countries during World War I and the years after. This time period covers the presidencies of Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. They each faced big challenges in how America interacted with the rest of the world.

President Wilson first tried to keep the U.S. out of World War I. But in 1917, he led the country into the war alongside the Allied Powers like Britain and France. After the war ended in 1918, Wilson played a key role at the Paris Peace Conference. He suggested his "Fourteen Points" plan, which aimed to create a "common peace" and stop future wars. Other Allied leaders didn't agree with all of Wilson's ideas, but they did agree to create the League of Nations. However, in the U.S., Senator Henry Cabot Lodge stopped the Treaty of Versailles from being approved. So, the U.S. never joined the League of Nations.

Warren G. Harding became president in 1921. He had campaigned against Wilson's policies. Harding rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and the U.S. still didn't join the League. His Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes, helped create the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. This agreement helped stop a race to build more warships among the big naval powers. Efforts to reduce weapons continued, leading to the 1930 London Naval Treaty. European countries also owed a lot of money from the war. The U.S. didn't forgive these debts, but Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover made deals to lower the amount owed. President Coolidge's main foreign policy effort was the Kellogg–Briand Pact. In this pact, countries agreed to stop using war to solve problems. The Great Depression started when Hoover was president, causing a worldwide economic crisis. During this time, Japan invaded Manchuria, and Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany.

In Latin America, Wilson sent soldiers to support governments the U.S. liked, similar to earlier presidents. But President Hoover eventually stopped these "Banana Wars". The U.S. also got involved in the Mexican Revolution during Wilson's time. Mexico remained an important foreign policy topic throughout the 1920s. After the October Revolution in Russia, Wilson sent American soldiers there as part of a larger Allied effort. Russia later became the Soviet Union in 1922. The U.S. didn't officially recognize the Soviet Union until 1933.

Contents

- Leading the Country's Foreign Policy

- Latin America: U.S. Actions (1913–1933)

- Other Countries and Regions (1913–1933)

- Images for kids

Leading the Country's Foreign Policy

This section looks at the presidents and their main advisors who shaped America's foreign policy during this time.

President Wilson's Approach (1913–1921)

Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, made all the big foreign policy decisions as president. This was from 1913 until he became very ill in late 1919. Other important people in his team included Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan and "Colonel" Edward M. House. Colonel House was Wilson's main foreign policy helper until 1919. Bryan quit in 1915 because he didn't agree with Wilson's tough stance against Germany after the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania. Robert Lansing then took his place.

Wilson believed in an idealistic way of dealing with other countries. He wanted nations to work together for peace and freedom. This was different from earlier presidents like Theodore Roosevelt, who focused more on America's own power and interests.

President Harding's Approach (1921–1923)

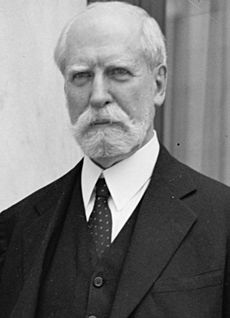

Warren G. Harding, a Republican, was president from March 1921 until he passed away in August 1923. Harding chose Charles Evans Hughes as his Secretary of State. Hughes had been a Supreme Court Justice and ran for president in 1916. Harding made it clear that Hughes would be in charge of foreign policy. This was different from Wilson, who managed international affairs very closely. Harding and Hughes talked often, and the president knew what was happening in the world. But he rarely changed Hughes's decisions.

Peace with Europe After World War I

Harding became president less than two years after World War I ended. His government faced many issues left over from the war. Harding decided that the U.S. would not join the League of Nations, not even a smaller version of it.

Since the Treaty of Versailles was not approved by the U.S. Senate, America was still technically at war with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. To make peace, the U.S. passed the Knox–Porter Resolution. This declared the U.S. was at peace and kept any rights given by the Versailles Treaty. New treaties were signed with Germany, Austria, and Hungary in 1921. These treaties included many parts of the Treaty of Versailles that didn't involve the League of Nations.

The U.S. government at first ignored messages from the League of Nations. But by 1922, the U.S. started working with the League through its consul in Geneva. The U.S. didn't join any League meetings about politics. However, it sent observers to meetings about technical or humanitarian issues. Harding also surprised many by supporting the U.S. joining the Permanent Court of International Justice, also known as the "World Court." But most senators didn't like this idea, and the proposal was stopped. The U.S. never joined the World Court.

Dealing with War Debts

After Harding took office, other countries asked the U.S. to reduce the huge war debts they owed. Germany also wanted to pay less in World War I reparations. The U.S. refused to make a big deal for all countries. Hughes worked out a deal for Britain to pay off its war debt over 62 years with low interest. This agreement was approved by Congress in 1923 and became a model for deals with other nations. Later, talks with Germany led to the Dawes Plan in 1924, which helped reduce their reparations payments.

Disarming the Military

After World War I, the U.S. had the biggest navy and one of the largest armies. But since there was no major threat to the U.S., Harding and the presidents after him reduced the size of the military. The army shrank to 140,000 soldiers. The navy was reduced to be equal in size to Britain's navy.

To stop a naval arms race, Senator William Borah pushed for a resolution to cut the American, British, and Japanese navies by 50 percent. With Congress's support, Harding and Hughes prepared for a naval disarmament conference in Washington. The Washington Naval Conference started in November 1921. Representatives from the U.S., Japan, Britain, France, Italy, China, and other countries attended. Secretary of State Hughes played a big role. He suggested that the U.S. would reduce its warships by 30 if Britain cut 19 ships and Japan cut 17. One journalist said Hughes "sank in thirty-five minutes more ships than all of the admirals of the world have sunk in a cycle of centuries."

The conference resulted in six treaties and twelve resolutions. These agreements limited the size of naval ships and dealt with other issues. The U.S., Britain, Japan, and France signed the Four-Power Treaty. In this treaty, they agreed to respect each other's territories in the Pacific Ocean. These four powers, plus Italy, also signed the Washington Naval Treaty. This treaty set limits on the size of battleships each country could have. In the Nine-Power Treaty, all countries agreed to respect China's "Open Door Policy." Japan also agreed to return Shandong to China. These treaties only lasted until the mid-1930s. Japan later invaded Manchuria, and the limits on weapons were ignored.

Relations with Latin America

Harding had spoken against Wilson's decision to send U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic during his campaign. Secretary of State Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries. These countries were worried about the U.S. using the Monroe Doctrine to interfere. When Harding became president, U.S. troops were also in Cuba and Nicaragua. Troops in Cuba left in 1921, but forces stayed in the other two nations. In April 1921, Harding approved the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia. This gave Colombia $25,000,000 because of the U.S. role in Panama becoming independent in 1903. Latin American nations were not fully happy because the U.S. wouldn't promise to stop interfering. But Hughes did promise to limit it to countries near the Panama Canal.

The U.S. had interfered many times in Mexico under Wilson. The Mexican government, led by President Álvaro Obregón, wanted the U.S. to officially recognize them. Hughes wanted a treaty first, which would include promises to pay Americans for losses since the 1910 Mexican Revolution. Obregón didn't want to sign a treaty before being recognized. He worked to improve relations with American businesses. This helped, and the U.S. officially recognized Obregón's government on August 31, 1923, shortly after Harding's death.

President Coolidge's Time (1923–1929)

Calvin Coolidge, a Republican, became president after Harding's death. He won a full term in 1924 and served until 1929. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes continued to lead foreign policy until he resigned in early 1925. Frank B. Kellogg then took over. Other important officials included Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon and Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover.

Reducing War Debts and Promoting Peace

Coolidge at first didn't want to forgive Europe's debt. But when France occupied the Ruhr region of Germany in 1923, he took action. Coolidge appointed Charles G. Dawes to lead a group to make a deal on Germany's reparations. The Dawes Plan restructured Germany's debt. The U.S. also loaned money to Germany to help it pay other countries. This plan helped the German economy grow and encouraged international cooperation.

Coolidge's main foreign policy effort was the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928. This treaty was named after Secretary of State Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The treaty, approved in 1929, made countries like the U.S., Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan agree to "renounce war, as an instrument of national policy." The treaty didn't stop all wars, but it became an important idea for international law after World War II. Coolidge's focus on reducing weapons helped cut military spending.

Immigration Changes

Immigration to the U.S. had grown a lot in the early 1900s, with many people coming from Southern and Eastern Europe. Many Americans were suspicious of these new immigrants. World War I and the "First Red Scare" (fear of communism) made these fears even stronger. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 reduced the number of immigrants allowed into the U.S. to 3 percent of a country's population based on the 1910 Census. This law greatly reduced immigration.

Later, Congress debated a permanent immigration law. Most leaders wanted to greatly limit immigration. Secretary of State Hughes didn't like the total ban on Japanese immigration, which went against an earlier agreement. But Coolidge signed the strict Immigration Act of 1924. This act limited annual immigration to 2 percent of each nationality's population in the U.S. as of the 1890 census. Asian immigrants were completely excluded. This law severely limited the flow of immigrants and aimed to keep America's existing ethnic makeup. It also helped protect American jobs by reducing competition from new arrivals.

President Hoover and the Great Depression (1929–1933)

Herbert Hoover, a Republican, became president after Coolidge in 1929. He kept many of the previous administration's officials, including Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. Henry L. Stimson became Hoover's Secretary of State. In October 1929, the Stock Market Crash happened, and the world economy plunged into the Great Depression. Because of this worldwide crisis, Hoover and Stimson became more involved in world affairs than earlier Republican presidents.

Dealing with Debts and Disarmament

When Hoover took office, a group in Paris created the Young Plan. This plan set up the Bank for International Settlements and partly forgave Germany's war reparations. Hoover was careful about agreeing to the plan. But he eventually supported it. However, the Great Depression hit Germany hard, and they couldn't pay reparations. Hoover then issued the Hoover Moratorium, a one-year pause on war loans from the Allies, if Germany also paused its reparations payments. This helped stabilize the European economy.

Hoover also made disarmament a priority. He hoped it would allow the U.S. to spend less on the military and more on domestic needs. Hoover and Stimson worked to extend the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. In 1930, the U.S. and other major naval powers signed the London Naval Treaty. This was the first time they agreed to limit the size of smaller warships. At the 1932 World Disarmament Conference, Hoover suggested worldwide cuts in weapons and banning tanks and bombers. But his ideas were not adopted.

Japan Invades Manchuria

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria in China. They defeated China's army and set up a puppet state called Manchukuo. The Hoover government didn't like the invasion. But they also wanted to avoid making Japan angry. Hoover saw Japan as a possible ally against the Soviet Union, which he thought was a bigger threat.

In response to Japan's invasion, Hoover and Secretary of State Stimson created the Stimson Doctrine. This stated that the U.S. would not recognize any territories gained by force. This idea was based on the 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact, where nations agreed to solve problems peacefully. After the invasion, Stimson and others thought war with Japan might be unavoidable. But Hoover kept pushing for disarmament. The Stimson Doctrine didn't have a big immediate impact. But it set the stage for strong American support for China against Japan later on.

The Rise of Hitler

In early 1933, during Hoover's last days in office, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. At first, many in the U.S. didn't take Hitler seriously. But Hitler quickly gained full control in Germany. He attacked the post-war order set by the Treaty of Versailles. Hitler preached a racist idea of Aryan superiority. His main foreign policy goal was to take over territory to Germany's east.

Latin America: U.S. Actions (1913–1933)

The Panama Canal and U.S. Influence

The Panama Canal opened in 1914. This was a long-term American goal to build a canal across Central America. The canal allowed ships to travel quickly between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. This created new opportunities for trade and allowed the Navy to move warships fast. In April 1921, the U.S. approved a treaty with Colombia. This treaty gave Colombia $25,000,000 for the U.S. role in Panama becoming independent in 1903. Latin American nations were not fully happy because the U.S. wouldn't promise to stop interfering. But Hughes did promise to limit it to countries near the Panama Canal.

U.S. Military Interventions

President Wilson wanted closer ties with Latin America. He hoped to create a Pan-American group to settle international disputes. But Wilson often sent troops into Latin American countries. He once said in 1913: "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men." In 1915, the U.S. intervened in Haiti after a revolt. This occupation lasted until 1919. The Dominican Republic had been under U.S. influence since Theodore Roosevelt's time. But it was still unstable. In 1916, Wilson sent troops to occupy that country too. Wilson also sent military forces to Cuba, Panama, and Honduras. A treaty in 1914 made Nicaragua another country under U.S. influence. U.S. soldiers stayed there throughout Wilson's presidency.

Harding had spoken against Wilson's military actions in Latin America. Secretary of State Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries. These nations were worried about the U.S. using the Monroe Doctrine to interfere. U.S. troops in Cuba left in 1921. But U.S. forces stayed in Nicaragua and Haiti throughout Harding's presidency.

The U.S. occupations of Nicaragua and Haiti continued under Coolidge. But Coolidge did pull American troops out of the Dominican Republic in 1924. Coolidge also attended a conference in Havana, Cuba, in 1928. There, he tried to make peace with Latin American leaders who were upset about America's interventions in the region.

President Hoover largely kept his promise not to interfere in Latin America's internal affairs. In 1930, he released the Clark Memorandum. This document rejected the idea that the U.S. could intervene in Latin American countries. Hoover did not completely stop using the military. He threatened to intervene in the Dominican Republic three times. He also sent warships to El Salvador to support the government against a revolution. But he ended the Banana Wars. He ended the occupation of Nicaragua and almost ended the occupation of Haiti. Franklin Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor policy" would continue this trend of less intervention in Latin America.

Mexico and U.S. Relations

Wilson became president during the Mexican Revolution. This revolution began in 1911. Shortly before Wilson took office, a military leader named Victoriano Huerta took power. Wilson didn't recognize Huerta's government and demanded democratic elections. When Huerta arrested U.S. Navy personnel, Wilson sent the Navy to occupy the Mexican city of Veracruz. This intervention helped convince Huerta to leave the country. A group led by Venustiano Carranza gained control, and Wilson recognized Carranza's government in October 1915.

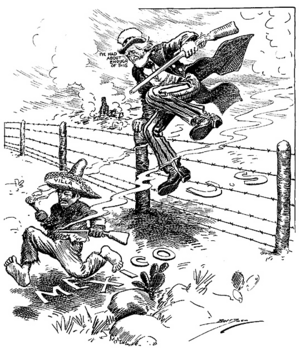

Chasing Pancho Villa

In early 1916, Pancho Villa attacked Columbus, a small American town in New Mexico. He killed eighteen Americans. This made many Americans demand action. Wilson ordered John J. Pershing and 4,000 troops to go into Mexico to capture Villa. Pershing's forces broke up Villa's groups. But Villa remained free, and Pershing continued to chase him deep into Mexico. President Carranza then turned against the Americans, saying they were invading. Tensions grew, almost leading to war. But the situation calmed down. Wilson ended Pershing's mission in Mexico in February 1917. This chase didn't catch Villa, but it made Pershing a national hero. Wilson later chose him to lead American forces in France during World War I.

Germany's Offer to Mexico

In January 1917, Germany's foreign minister sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram. This secret message invited Mexico to join Germany in a war against the U.S. Washington learned about this on February 23. It was important to improve relations with Mexico. Wilson officially recognized Carranza's government in April, after Congress declared war on Germany. Mexico was then free to continue its revolution without American pressure.

After the Revolution

A new Mexican government under President Álvaro Obregón sought recognition. But the Wilson government refused. Under Harding, Secretary of State Hughes sent a draft treaty to Mexico in May 1921. This treaty included promises to pay Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution. Obregón didn't want to sign a treaty before being recognized. He worked to improve relations with American businesses. This helped, and the U.S. officially recognized Obregón's government on August 31, 1923.

In 1924, Plutarco Elías Calles became President of Mexico. Calles wanted to limit American property claims and take control of Catholic Church properties. However, U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow convinced Calles to let Americans keep their property rights from before 1917. Mexico and the U.S. had good relations for the rest of Coolidge's presidency. Morrow also helped end the Cristero War, a Catholic revolt against Calles's government.

To help with unemployment, Hoover wanted to cut immigration to the United States. In 1930, he ordered that people needed a job before moving to the U.S. Secretary of Labor William N. Doak also started a campaign to find and deport illegal immigrants. This campaign mostly affected Mexican Americans, especially those in Southern California. Many people were sent back to Mexico. During the 1930s, about one million Mexican Americans were forced to return to Mexico. About sixty percent of them were U.S. citizens by birth.

Other Countries and Regions (1913–1933)

Russia and the Soviet Union

After Russia left World War I in 1917, the Allies sent troops there. They wanted to stop Germany or the Bolsheviks from taking weapons and supplies. Wilson didn't like the Bolsheviks, but he worried that foreign interference would only make them stronger. Britain and France pushed him to intervene. Wilson agreed, hoping it would help him in post-war talks and limit Japan's influence in Siberia. The U.S. sent armed forces to help Czech soldiers leave along the Trans-Siberian Railway. They also held key port cities. Even though they were told not to fight the Bolsheviks, U.S. forces did have some armed conflicts with the new Russian government.

Commerce Secretary Hoover led the policy on Russia in the Harding administration. He supported aid and trade with Russia. When a famine hit Russia in 1921, Hoover's American Relief Administration worked with the Russians to provide help. This effort may have saved as many as 10 million people from starving. American business people invested in the Russian economy. But many of these investments failed due to Russian trade rules. Russian and Soviet leaders hoped these connections would lead to the U.S. recognizing their government. But communism was very unpopular in the U.S., so this didn't happen.

By the late 1920s, the Soviet Union had normal relations with most European countries. By 1933, American fears of communism had lessened. Businesses and newspapers called for diplomatic recognition. After the Soviets promised not to spy, Roosevelt officially recognized relations in November 1933.

Japan

Relations with Japan improved after the Washington Naval Treaty was signed. They got even better when the U.S. helped Japan after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. This earthquake killed up to 200,000 Japanese people and left 2 million homeless. However, relations worsened with the Immigration Act of 1924. This law banned immigration from Japan to the U.S. U.S. officials encouraged Japan to protest the ban. But Japanese threats actually made supporters of the law more determined. The immigration law caused a big backlash in Japan. It made those in Japan who favored expansion over cooperation with Western powers stronger.

China

The Coolidge administration at first avoided getting involved with the Republic of China. This government was led by Sun Yat-sen and later by Chiang Kai-shek. The U.S. protested when China's Northern Expedition led to attacks on foreigners. The U.S. also refused to change old treaties made with China when it was under the Qing dynasty. In 1927, Chiang removed Communists from his government and started seeking U.S. support. Secretary of State Kellogg agreed to let China set its own import duties on American goods. This was a step towards closer relations with China.

Images for kids

-

Gen. John J. Pershing

-

The "Big Four" leaders at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Wilson is standing next to Georges Clemenceau on the right.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |