History of atomic theory facts for kids

Atomic theory is a big idea in science. It says that everything around us, called matter, is made up of tiny particles called atoms. For a long time, people thought atoms were the smallest things and couldn't be split. But scientists later found out that atoms themselves are made of even smaller parts! This theory is super important. It helps us understand how the world works, from tiny particles to huge stars.

Contents

- Early Ideas About Atoms

- Chemistry Before Atoms

- Dalton's Atomic Theory

- Avogadro's Law

- Defining Atoms and Molecules

- Isomers: Different Arrangements of Atoms

- Mendeleev's Periodic Table

- Kinetic Theory of Gases

- Thomson's Plum Pudding Model

- Discovery of the Nucleus

- Discovery of Isotopes

- The Atomic Number

- Bohr's Model of the Atom

- Discovery of the Proton

- Quantum Mechanical Models

- Discovery of the Neutron

- See also

Early Ideas About Atoms

The idea that everything is made of tiny, unbreakable pieces is very old. Ancient thinkers, like the Greeks, had this idea. They even gave us the word "atom," which means "indivisible." But these early ideas were based on thinking, not on scientific experiments. Modern atomic theory uses experiments and evidence to understand atoms.

Chemistry Before Atoms

Before we fully understood atoms, chemists made important discoveries. In the late 1600s, Robert Boyle helped us understand what a chemical element is. He showed it's different from a chemical compound.

Later, in the 1700s, Antoine Lavoisier made big steps. He proved that elements like hydrogen and oxygen combine in fixed ways to make compounds like water. He also showed that matter is never created or destroyed in a chemical reaction. This is called the law of conservation of mass. It means the total weight of substances stays the same, even if they change form.

Then, Joseph Proust discovered the law of definite proportions. This law says that a specific chemical compound always has the same elements in the same proportions by weight. For example, water is always H₂O, no matter where it comes from.

Dalton's Atomic Theory

In the early 1800s, a scientist named John Dalton looked at how elements combine. He noticed a cool pattern: when two elements form different compounds, the amounts of one element combine with a fixed amount of the other in simple whole-number ratios. This is called the law of multiple proportions.

For example, Dalton studied compounds of nitrogen and oxygen. He found that for a certain amount of nitrogen, the oxygen amounts were in ratios like 1:2:4. This made him think that elements combine in specific, tiny units. He called these units atoms.

Dalton's atomic theory had a few main ideas:

- All atoms of one element are exactly alike and have the same weight.

- Atoms of different elements have different weights.

- Atoms cannot be created or destroyed in chemical reactions. They just rearrange.

- Atoms combine in simple whole-number ratios to form compounds.

Dalton's ideas helped explain many chemical laws. He thought of atoms as tiny, solid spheres. He even used the term "compound atom" for what we now call a molecule. For example, he thought water was made of one hydrogen atom and one oxygen atom (HO). We now know it's H₂O. His system for measuring atomic weights wasn't perfect, but it was a huge step forward!

Avogadro's Law

Later, in 1811, Amedeo Avogadro helped fix some issues with Dalton's ideas. He proposed an important law about gases. Avogadro's law states that if you have equal amounts of any two gases, at the same temperature and pressure, they will contain the same number of molecules.

This idea helped scientists figure out the correct formulas for many compounds. For example, it showed that water is H₂O (two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom), not just HO as Dalton first thought. Avogadro's work was key to understanding how atoms combine to form molecules.

Defining Atoms and Molecules

For a while, scientists had different ideas about what "atom" and "molecule" meant. The word "atom" suggested something that couldn't be divided. But Dalton used "compound atom" for things like carbon dioxide, which could be broken down.

In 1860, chemists held a big meeting called the Karlsruhe Congress. Here, they finally agreed on clear definitions. An atom is the basic particle of an chemical element. A molecule is a group of two or more atoms joined together. This helped everyone in chemistry speak the same language.

Isomers: Different Arrangements of Atoms

Scientists discovered that some substances could have the exact same atoms but different properties. For example, silver fulminate and silver cyanate both have silver, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms. But they are different chemicals!

In 1830, Jöns Jacob Berzelius called this phenomenon isomerism. Later, in 1860, Louis Pasteur suggested that the atoms in isomers might just be arranged differently.

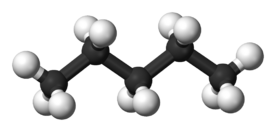

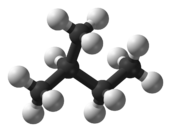

In 1874, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff proposed that carbon atoms bond in a special shape, like a pyramid with four sides (a tetrahedron). This idea helped explain how different arrangements of atoms could lead to different isomers. For example, he correctly predicted there would be three different ways to arrange the atoms in pentane (C₅H₁₂).

Mendeleev's Periodic Table

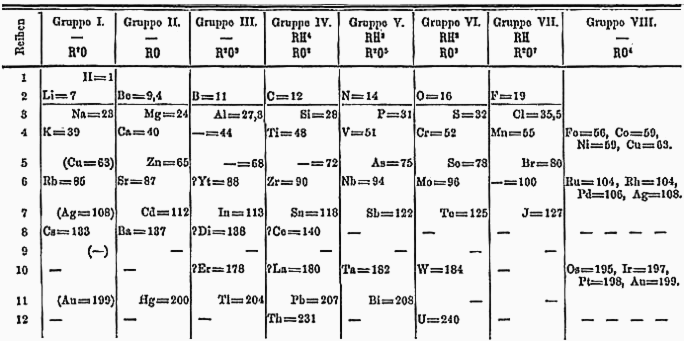

In 1869, Dmitrii Mendeleev made a huge breakthrough. He arranged the known elements by their atomic weight and noticed a repeating pattern in their properties. This was the first periodic table.

Mendeleev's table was amazing because it could predict new elements! He left gaps for elements that hadn't been discovered yet, like scandium, gallium, and germanium. When these elements were found later, their properties matched his predictions. The periodic table showed that elements could be grouped by their atomic weight and how they combine with other atoms.

Today, the periodic table is arranged by atomic number (the number of protons), not just atomic weight. This change happened after more discoveries about the atom's inner structure.

Kinetic Theory of Gases

In 1738, Daniel Bernoulli suggested that the pressure and heat of gases come from their tiny particles constantly moving. This idea, called the kinetic theory of gases, helped explain how gases behave.

Later, in the 1800s, scientists like James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann further developed this theory. They showed that gas particles move at different speeds, and that temperature is related to their average speed.

Brownian Motion: Seeing Evidence of Atoms

In 1827, a botanist named Robert Brown noticed something strange. Tiny dust particles floating in water constantly jiggled around. He didn't know why.

In 1905, Albert Einstein figured it out! He theorized that the jiggling was caused by invisible water molecules bumping into the dust particles. He even created a mathematical model to describe this "Brownian motion."

In 1908, Jean Perrin proved Einstein's theory with experiments. He used Einstein's equations to measure the size of atoms, providing strong evidence that atoms really exist and are always moving.

Thomson's Plum Pudding Model

For a long time, atoms were thought to be the smallest things. But in 1899, J. J. Thomson discovered something even smaller: the electron! He found these tiny, negatively charged particles using special glass tubes called Crookes tubes.

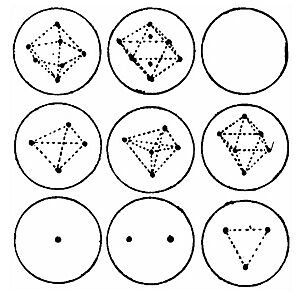

Thomson realized that if atoms contain negative electrons, they must also have something positive to balance the charge and make the atom neutral. In 1904, he proposed a new model for the atom. He imagined the atom as a sphere of positive charge, with tiny negative electrons scattered throughout it, like raisins in a plum pudding. This was called the plum pudding model.

Thomson's model was a big step, but it couldn't explain everything about atoms, like why they emit specific colors of light.

Discovery of the Nucleus

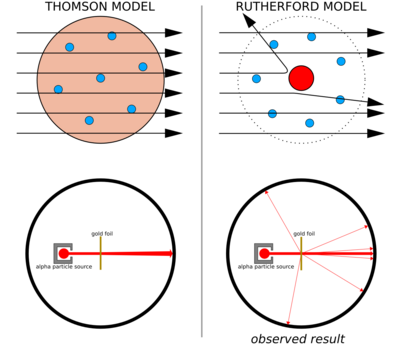

Thomson's plum pudding model was challenged in 1911 by his former student, Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford and his team, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, conducted famous experiments. They shot tiny, positively charged particles (called alpha particles) at a very thin sheet of gold foil.

They expected the alpha particles to pass straight through the gold atoms, with only slight deflections. But to their surprise, some particles bounced back! It was like shooting a cannonball at tissue paper and having it bounce back.

Rutherford realized this meant the positive charge and most of the mass of an atom must be concentrated in a tiny, dense center. He called this center the atomic nucleus. This discovery completely changed our understanding of the atom.

Discovery of Isotopes

Around the same time, Frederick Soddy was studying radioactive materials. He found that some elements, even though they were chemically identical, had different atomic weights. He called these variations isotopes.

In 1919, Francis Aston built a special machine called a mass spectrograph. This machine could separate atoms based on their mass. Aston used it to confirm Soddy's idea, finding isotopes for many elements.

Aston also noticed that the mass of an isotope was almost always a whole number multiple of hydrogen's mass. The small differences he found helped scientists understand that some mass is converted into energy when atoms form, according to Albert Einstein's famous E=mc² equation.

The Atomic Number

Before 1913, the periodic table was mostly organized by atomic weight. But some elements seemed out of place. For example, cobalt was heavier than nickel, but its chemical properties suggested it should come before nickel.

In 1913, Antonius van den Broek suggested that elements should be ordered by their nuclear charge, not just their weight. This charge was called Z.

Later, Henry Moseley used X-ray experiments to confirm this. He found that each element had a unique number of positive charges in its nucleus. This number, called the atomic number, became the true way to organize the periodic table. It perfectly explained why cobalt and nickel were placed where they were. The atomic number is the number of protons in an atom's nucleus.

Bohr's Model of the Atom

After Rutherford discovered the nucleus, scientists still wondered how electrons were arranged around it. In 1912, Niels Bohr joined Rutherford's lab and developed a new model.

Bohr used ideas from Max Planck and Albert Einstein about energy coming in tiny packets called quanta. Bohr proposed two main ideas: 1. Electrons orbit the nucleus in specific paths or "energy levels." 2. Electrons can jump between these energy levels by absorbing or emitting light. When they jump, they release or absorb a specific amount of energy.

Bohr's model successfully explained why hydrogen atoms emit light in specific colors, matching a formula discovered earlier by Johann Balmer. This was a huge success! However, Bohr's model couldn't fully explain more complex atoms or all the details of hydrogen's light spectrum.

Discovery of the Proton

In 1917, Ernest Rutherford made another important discovery. He bombarded nitrogen gas with alpha particles and saw hydrogen ions being released. He realized that the alpha particles were hitting the nitrogen nuclei and knocking out these hydrogen ions.

Rutherford concluded that the hydrogen nucleus was a fundamental particle with a positive charge. He named this particle the "proton" in 1920. This meant that the nucleus of every atom contains protons. The number of protons in an atom is its atomic number.

Quantum Mechanical Models

Bohr's model was good, but it wasn't perfect. In 1924, Louis de Broglie suggested that all particles, including electrons, could also behave like waves. This was a revolutionary idea!

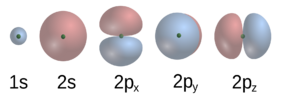

Inspired by this, Erwin Schrödinger developed an equation that described electrons as "wave functions" instead of tiny points orbiting the nucleus. This new approach, called quantum mechanics, could explain many things Bohr's model couldn't.

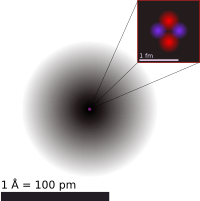

Instead of fixed orbits, quantum mechanics describes atomic orbitals. These are regions around the nucleus where an electron is most likely to be found. The shapes of these orbitals are complex and depend on the electron's energy. This wave-like view of electrons is part of what we call Wave–particle duality, meaning particles can act like both waves and particles.

Discovery of the Neutron

For a while, scientists thought atomic nuclei contained protons and "nuclear electrons" to explain their mass and charge. But this idea had problems.

In 1932, James Chadwick discovered a new particle. He found that when beryllium was hit with alpha particles, it released a very penetrating, electrically neutral radiation. He realized this radiation was made of particles that had about the same mass as a proton, but no electric charge. He called this new particle the "neutron."

The discovery of the neutron completed our understanding of the basic parts of the atom. We now know that the nucleus contains both protons (positive charge) and neutrons (no charge). Electrons (negative charge) orbit the nucleus. This model helps us understand the mass of atoms and why isotopes exist.

See also

- Spectroscopy

- Atom

- History of molecular theory

- Discovery of chemical elements

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

- Kinetic theory of gases