History of libraries facts for kids

Imagine a world without books! For thousands of years, people have collected writings to share knowledge and stories. The history of libraries is all about how these collections grew, changed, and became places for everyone to learn. From ancient clay tablets to digital books, libraries have always been important centers for learning and culture. They show how people have kept records, shared ideas, and learned from each other throughout time.

Contents

- Ancient Libraries: Clay Tablets and Papyrus Scrolls

- Libraries in the Classical World

- Libraries in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages

- Islamic Libraries: Centers of Learning

- Asian Libraries: Paper and Printing

- European Libraries in the Middle Ages

- Renaissance Libraries: New Ideas and Collections

- Enlightenment Era Libraries: Opening to the Public

- Libraries in Colonial British America

- National Libraries: Collections for a Nation

- Modern Public Libraries: For Everyone

- Images for kids

Ancient Libraries: Clay Tablets and Papyrus Scrolls

The very first libraries appeared about 5,000 years ago in a region called the Fertile Crescent. This area, from Mesopotamia to Egypt, is where writing began. These early libraries were mostly archives, holding records of business deals and inventories.

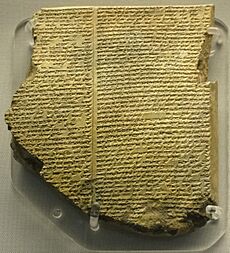

The first "books" were clay tablets. They were about an inch thick and came in different shapes. People wrote on soft, damp clay, then let it dry in the sun or baked it in a kiln to make it hard. For storage, tablets were stacked on their sides. A title written on the edge helped people know what was inside.

In Ancient Egypt, government and temple records were kept on papyrus scrolls. One famous ancient library was the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. Over 30,000 clay tablets were found there! These tablets contained amazing stories, religious texts, and scientific information. They included the Epic of Gilgamesh and texts about stars and planets.

These tablets were stored in wooden boxes, baskets, or on clay shelves. Librarians used "colophons" (like a title on the spine of a book) to identify the contents. Tablets were organized by subject and size.

Legend says the philosopher Laozi was a book keeper in China's earliest library, belonging to the Imperial Zhou dynasty. This shows that even then, people were organizing books.

Libraries in the Classical World

Ancient Persia, during the Achaemenid Empire, had great libraries. They kept administrative documents like records of transactions and government orders. They also collected books on science, astronomy, history, and philosophy. A huge collection of clay tablets found in Persepolis shows how well the Achaemenids recorded information. These tablets covered everything from sales to daily life.

Some historians believe that many books from Persian libraries were moved to Egypt after Alexander III of Macedon conquered Persia. These books were then translated and became part of the famous Library of Alexandria.

The Library of Alexandria in Egypt was the biggest and most important library of the ancient world. It was a major center for learning for centuries. It was started by Ptolemy I Soter or his son Ptolemy II of Egypt. This library had an early system for organizing its scrolls.

Another important library was the Library of Celsus in Ephesus, Turkey. It was built around 135 AD to hold 12,000 scrolls. It also served as a tomb for Celsus, a Roman Senator. Today, only the front of the building remains.

Roman Libraries: Public Access and Private Collections

In ancient Greece, private libraries of written books began to appear in the 5th century BC. By the time of Augustus, Rome had public libraries near its forums. These included libraries in the Porticus Octaviae and the Ulpian Library.

Private libraries also became popular among wealthy Romans. Some owners cared more about showing off their collections than reading them! These libraries were often found in grand homes and villas. For example, at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, a Greek library was partly saved by volcanic ash.

Rome's first public library was created by Asinius Pollio, a supporter of Julius Caesar. He wanted a library that would make Rome as prestigious as Alexandria. His library, the Anla Libertatis, was the first to separate books into Greek and Latin sections. Later, Emperor Augustus built two more public libraries.

Emperors Tiberius and Vespasian also added libraries. The Ulpian Library, built by Emperor Trajan around 112 AD, was one of the best preserved. It had separate rooms for Greek and Latin texts.

Unlike Greek libraries, Roman readers could directly access the scrolls. They would read or copy books in the same room where they were stored. Most large Roman baths also had libraries, usually with two rooms: one for Greek and one for Latin texts.

Libraries used scrolls made of parchment (animal skin) or papyrus (plant material). Most collections were private, but some institutional libraries were open to educated people. Books were usually kept in a small room, and staff would get them for readers. Many books were religious, like the Bible. In the early Middle Ages, Aristotle was very popular.

In China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered most books destroyed in 213 BC. But the Han Dynasty later reversed this. They created three imperial libraries. Liu Xin, a library curator, created the first library classification system. At this time, library catalogs were written on silk scrolls.

New inventions like paper and block printing helped books spread. Wood-block printing allowed many copies of Buddhist texts to be made. In the 11th century, movable type was developed in China and Korea.

Libraries in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages

In Persia, during the Sassanid Empire, rulers and priests again focused on collecting books. Many Zoroastrian fire temples had libraries. The Academy of Gundeshapur, built by Shapur I, had a huge library, a hospital, and an academy. They sent people to China, Rome, and India to collect and translate manuscripts.

As the Roman Empire changed, books and libraries moved east to the Byzantine Empire. Four types of libraries were created there: imperial, patriarchal, monastic, and private.

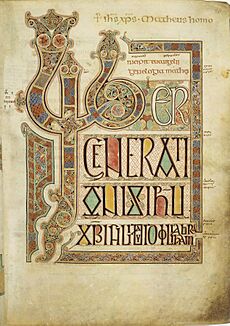

Christianity became a major force. In the West, many classical Greek works were lost because only Christian texts were preserved. But in the East, many Greek and Roman texts were copied. Monks in scriptoriums (writing rooms) worked hard to copy these texts into codexes (early forms of books). These monastic libraries became very large and important for preserving knowledge.

The Imperial Library of Constantinople was a huge storehouse of ancient knowledge. Emperor Constantius II made this dream a reality. He hired a philosopher named Themistius to build the library and collect classical authors like Plato and Aristotle. At its peak in the 5th century, it had 120,000 volumes, making it the largest library in Europe. Sadly, it was destroyed by fires several times.

Patriarchal libraries were theological libraries, often connected to the church. They also faced destruction due to religious conflicts. Small private libraries were owned by church members, aristocrats, and wealthy book lovers.

In the 6th century, the great libraries of Constantinople and Alexandria were still important. Cassiodorus tried to preserve Greek and Roman texts in his monastery library in Italy, but it was eventually lost. The theological school of Caesarea had a huge library with over 30,000 manuscripts.

Islamic Libraries: Centers of Learning

Muslims were inspired to collect writings to preserve the Quran and the teachings of Muhammad. Mosques became centers of learning, with libraries holding books on philosophy, geography, and science.

By the 8th century, Muslims learned papermaking from China and turned it into a big industry. This made books easier to make and more widely available. With a focus on science and translation, public and private libraries grew across Islamic lands.

The Abbasid Caliphs were big supporters of learning. They created amazing royal libraries in Baghdad. They paid translators and copyists to translate books from Persian, Greek, Roman, and Sanskrit into Arabic. Libraries became places where books were collected, read, copied, and borrowed. Many scholars and wealthy people donated their book collections to mosques, shrines, and schools.

Local rulers also built beautiful public libraries. A Muslim geographer named Al-Maqdisi was amazed by a library in Shiraz. It had buildings surrounded by gardens, lakes, and waterways, with 360 rooms! Each department had catalogs, and the rooms were furnished with carpets.

This golden age of Islamic learning ended when many libraries were destroyed by Mongol invasions or wars. Some valuable manuscripts were moved to European libraries. However, some medieval libraries, like those in Chinguetti, West Africa, still exist today.

Christian monks in Spain and Sicily copied books from these Islamic libraries. These copies, along with others preserved by Christian monks, became the foundation of modern libraries.

Famous Islamic Libraries

- Bait al Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad (9th Century): Founded by Caliph Al-Ma'mun, this science center had an observatory and a rich library. It was famous for translating Greek, Persian, Indian, and Syriac texts into Arabic.

- Nuh Ibn Mansour Samani Library in Bukhara (10th century): The Samanid rulers loved culture and science. The famous scholar Avicenna visited this library and described it as extraordinary, with many rooms full of books.

- Baha al-Dowleh and Azod al-Dowleh Daylami Library in Shiraz (10th century): These rulers owned one of the most important libraries in Islamic lands. A historian said it had a copy of every book he had ever seen.

- Abu-Nasr Shapur Ibn Ardeshir Library in Baghdad (10th century): This public library was said to hold 10,000 volumes before it was destroyed in a fire.

- Sahib ibn Abbad Library in Rey (10th century): This legendary public library had around 200,000 volumes. Its catalog alone was said to be 10 volumes long!

- Greater Merv Libraries: A geographer named Yaqut al-Hamawi found ten amazing libraries here. He said some books were unique and could not be found anywhere else. Patrons could borrow many books for long periods.

- Rab'-e Rashidi Library in Maragheh (13th century): Founded by Rashid al-Din Hamadani, this library allowed researchers to study and copy resources. Books could be used inside, and borrowing required a deposit.

- Timbuktu Library (11th century): In Africa, this library held many important manuscripts for over 600 years. Sadly, many were destroyed in an invasion, but about 700,000 manuscripts still survive.

Asian Libraries: Paper and Printing

The spread of religion and philosophy in South and East Asia led to the growth of writing and books. Chinese emperors strongly supported this. Chinese printing and papermaking, which came before Western methods, created a thriving book culture.

Several Asian religions and philosophies encouraged learning and book collecting: Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Jainism. Jainism, a faith in India, had a tradition of scholarship. Early Jains created religious writings and some of Asia's first libraries. These "Jain Knowledge Warehouses" preserved hundreds of thousands of handwritten manuscripts.

The invention of paper in China allowed for early forms of printing, like stone-rubbing. Later, the Chinese used inked woodblocks to print materials. A major Buddhist text, the Tripiṭaka, was published in 5,000 volumes using over 130,000 woodblocks. In the 11th century, movable type was developed in China and Korea.

In Southeast Asia, Buddhist scriptures and histories were stored in libraries. In Burma, the royal Pitakataik library was said to be founded by King Anawrahta. In Thailand, libraries called ho trai were built on stilts above ponds to protect books from insects.

European Libraries in the Middle Ages

During the Early Middle Ages, monastery libraries grew, like the one at the Abbey of Montecassino in Italy. Books were very valuable because they were copied by hand. Sometimes, books were even chained to shelves to prevent theft. Scribes often added "book curses" to the last page, warning thieves of bad luck!

Despite this, many libraries loaned books if people left a deposit. Lending helped books be copied and spread. In 1212, a council in Paris said that lending books was "one of the chief works of mercy."

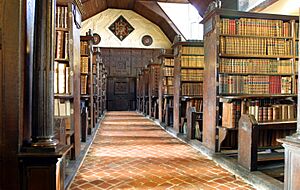

Early monastery libraries had lecterns with chained books. Shelves built above these lecterns were the start of modern bookcases. The chain was attached to the front edge of the book, not the spine. Bookcases were often placed perpendicular to walls to get the most light from windows.

Monasteries were where most books were made. Monks and lay brothers copied and bound books. Artists added beautiful designs and pictures. A large monastery might have 40 scribes, with each scribe copying about two books a year.

Monastery librarians, called armarius, kept track of the books. They organized the library and the scriptorium, managed inventory, and oversaw the scribes. Their lists helped them know what books they had.

Medieval libraries, being part of the Catholic Church, often did not include books considered "heretical" or "pagan," like some works by Plato and Aristotle.

In Eastern Christianity, monastery libraries also kept important manuscripts. Famous ones include those on Mount Athos and the Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt. Jewish medieval libraries were mostly private or semi-private, as there were few institutions dedicated to making and keeping manuscripts.

Renaissance Libraries: New Ideas and Collections

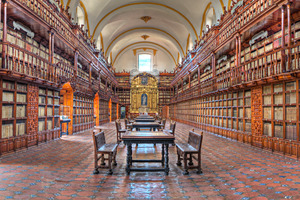

From the 15th century, libraries in Italy became centers for humanist scholars. Malatesta Novello founded the Malatestiana Library. Cosimo de Medici started his own collection, which became the Laurentian Library in Florence. In Rome, Pope Nicholas V brought together papal collections, which Pope Sixtus IV later housed in the Vatican Library.

The Bibliotheca Corviniana in Hungary, started by King Matthias Corvinus, was one of the first and largest Renaissance Greek-Latin libraries. It had about 3,000 valuable books.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, more private libraries were created in Rome, like the Biblioteca Vallicelliana and the Biblioteca Angelica. This trend spread outside Italy, for example, the Bibliotheca Palatina in Heidelberg.

These libraries had fewer books than modern ones, but they held many valuable Greek, Latin, and Biblical manuscripts. After the invention of the printing press, libraries began collecting printed books as well as manuscripts. This shift, from about 1550 to 1650, meant libraries started focusing on practical information, not just rare, beautiful books. For example, the library at the Ducal Palace in Urbino, Italy, had an old section for family history and a new section for research and discussion.

The Tianyi Chamber, founded in China in 1561, is the oldest existing library there. It once had 70,000 old books.

Enlightenment Era Libraries: Opening to the Public

The 17th and 18th centuries were a "golden age" for libraries in Europe. Many important libraries were founded. The Francis Trigge Chained Library in Grantham, England, founded in 1598, is considered an "ancestor of public libraries" because anyone could use it, not just members of a college or church. It had over 350 books, including both Catholic and Protestant texts, which was unusual for the time.

Thomas Bodley founded the Bodleian Library in 1602, which was open to "the whole republic of the learned." Chetham's Library in Manchester, opened in 1653, claims to be the oldest public library in the English-speaking world.

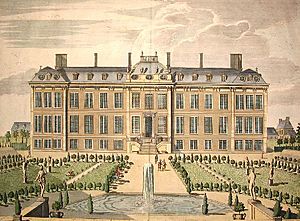

The Bibliothèque Mazarine in Paris started as the personal library of Cardinal Mazarin. He opened it to scholars in 1643 and later left it to a college he founded. Other major libraries established during this time include the Austrian National Library in Vienna and the Prussian State Library in Berlin.

This period also saw conflicts, like the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). Books were often taken as spoils of war. For example, the contents of the Bibliotheca Palatina were sent to the Vatican. This movement of books helped new libraries grow across Europe.

The printing press made books more common and easier to trade. Book fairs became popular places for merchants to sell books.

Collectors of this period helped shape how libraries look today. Cardinal Mazarin's library was "open to everybody without exception." Sir Robert Cotton, 1st Baronet, of Connington, organized his library by placing busts of ancient Romans on his shelves and cataloging books based on the bust and their position.

By the 18th century, libraries were becoming more public and often lent books. Before this, public libraries were often connected to churches and chained their books. Access was not always open to everyone.

Even though the British Museum had over 50,000 books, it was not fully open to the public. People needed passes, and tours were often too short. However, some libraries, like the Ducal Library at Wolfenbüttel, were open every weekday and had many different types of users.

Libraries in Colonial British America

The first library in British America was founded by John Harvard. He donated his collection of 400 books and his estate to a seminary, which became Harvard University. This library grew to be the largest in British America, with 5,000 books by 1764. Sadly, a fire destroyed it that year, but the university rebuilt it.

Benjamin Franklin helped start the first subscription library in Colonial British America. He and his friends formed a club called Junto. They shared books, and Franklin suggested putting all their books in one place. In 1731, they started the Library Company of Philadelphia. Members paid a fee and annual dues. This idea became very popular, and many subscription libraries opened across the colonies.

Subscription Libraries: Sharing Books for a Fee

At the start of the 19th century, there were almost no public libraries that were free and funded by the public. Most libraries were private or institutional.

The growth of secular literature led to more lending libraries, especially commercial subscription libraries. These libraries charged high fees or required members to buy shares. They often focused on subjects like biography, history, and philosophy, rather than just fiction.

Unlike public libraries today, access was usually limited to members. Some of the earliest were in England in the late 17th century, like Chetham's Library (1653). In the American colonies, Benjamin Franklin's Library Company of Philadelphia (1731) was a famous example.

Parochial libraries, connected to churches, also appeared in Britain in the early 18th century. They helped pave the way for local public libraries.

The demand for fiction led to the rise of circulating libraries. These also charged fees and offered popular novels alongside serious subjects.

Subscription libraries were often created by local communities. They aimed to build permanent collections of books. Members elected committees to choose books that would benefit everyone.

By 1800, there were over 200 commercial circulating libraries in Britain. These were like today's rental collections, often focusing on fashionable clients.

Private Libraries: Exclusive Collections

Private subscription libraries were similar to commercial ones but had more control over who could join and what books they had. Many were "gentlemen only" libraries. Membership was limited to proprietors or shareholders.

The Liverpool Subscription library became the Athenaeum in 1798. It had a newsroom and coffeehouse. Its most popular sections were history, antiquities, geography, and literature.

Private subscription libraries usually avoided cheap fiction and focused on respectable books. Subscribers were often landowners, gentry, and professionals.

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the need for books grew among the working classes due to the Industrial Revolution. Libraries for tradesmen began to appear, like the Economical Library in Kendal (1797) and the Artizans' library in Birmingham (1799).

Benjamin Franklin's "Junto" club in Philadelphia was a key example. Members pooled their money to buy books, creating a shared library.

National Libraries: Collections for a Nation

National libraries began as royal collections. This era is sometimes called the "golden age of libraries" because libraries became symbols of national pride.

In England, John Dee proposed a national library in 1556, but it wasn't built. Sir Robert Cotton, 1st Baronet, of Connington, a wealthy collector, gathered the richest private collection of manuscripts. After monasteries were dissolved, many valuable manuscripts were scattered. Sir Robert bought and saved these ancient documents. His grandson later donated the library to the nation, forming the basis of the British Library.

Growth of National Libraries

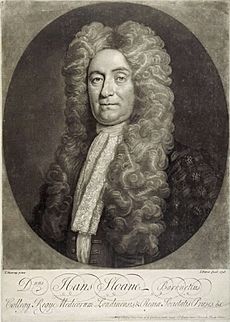

The first true national library was founded in 1753 as part of the British Museum. This new institution was unique: national, not belonging to a church or king, open to the public, and aiming to collect everything. It was based on the collection of Hans Sloane, who left his 40,000 books and 7,000 manuscripts to the nation. The British Museum Act 1753 also included the Cotton and Harleian libraries. In 1757, King George II granted it the right to a copy of every book published in the country, ensuring its collection would grow forever.

Anthony Panizzi became the head librarian of the British Library in 1856. He modernized it, and its collection grew to 540,000 volumes, making it the largest in the world at the time. Its famous circular Reading Room opened in 1857. Panizzi also created new cataloging rules that influenced library catalogs for centuries.

In France, the Bibliothèque Mazarine started as a royal library in 1368. After being dispersed, it was rebuilt and became the largest and richest collection of books in the world under librarian Jacques Auguste de Thou. It opened to the public in 1692. During the French Revolution, the private libraries of aristocrats were seized, and the library's collection grew to over 300,000 volumes. It was renamed the Bibliothèque Nationale and became the property of the French people.

Expanding National Collections

In the United States, James Madison first suggested a congressional library in 1783. The Library of Congress was established in 1800. It started with 740 books and 3 maps. In 1814, British troops burned Washington D.C., destroying most of the library. Soon after, Thomas Jefferson sold his personal library to Congress to replace what was lost. His collection, much larger and more diverse, became the core of the modern Library of Congress.

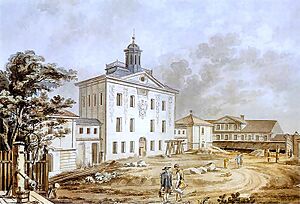

The Imperial Public Library was founded in 1795 by Catherine the Great. Its foreign-language department began with the Załuski's Library from Poland, which had 420,000 volumes.

Germany's first national library, the Reichsbibliothek, was set up during the German revolutions of 1848. In 1912, the German National Library was founded in Leipzig, collecting all German publications.

Modern Public Libraries: For Everyone

Canada: Early Public Library Laws

Personal book collections came to Canada with French settlers in the 16th century. In Quebec City, the Jesuit College was established in 1635. In 1882, the province of Ontario passed laws for free public libraries.

United Kingdom: The Birth of Free Public Libraries

By the mid-19th century, England and Scotland had many subscription libraries. However, the modern public library system in Britain began with the Public Libraries Act 1850. This law allowed local towns to create free public libraries. It was a big step towards providing free access to information for everyone.

In the 1830s, there was a movement for social reform in the UK. People worried that workers had too much free time and wanted to encourage them to do morally uplifting activities, like reading. James Silk Buckingham introduced a bill in 1835 to allow towns to tax for libraries and museums. This influenced William Ewart and Joseph Brotherton, who helped pass the Museums Act 1845.

Ewart and Brotherton then pushed for public libraries. Their report suggested that libraries would encourage good habits. They recommended government grants and allowing taxes for libraries. The Public Libraries Act passed in 1850, allowing cities over 10,000 people to tax for libraries. Most Members of Parliament believed libraries would help people improve themselves and reduce crime.

The Francis Trigge Chained Library (1598) was an early example of a library for the general public in England. The modern free public library system really started in the UK in 1847. The Public Libraries Act of 1850 allowed cities to levy taxes for libraries.

Salford Museum and Art Gallery opened in 1850 as the first unconditionally free public library in England. The library in Manchester was the first to offer free lending without a subscription in 1852. By 1900, over 300 cities had established free libraries. This marked the true beginning of the public library as we know it. These laws influenced similar ones in other countries, like the US.

World War II brought nightly bombing raids from Germany, and many libraries in England suffered. Some libraries lost entire collections, like Coventry and Plymouth. At Liverpool, a bomb attack destroyed many books and the main catalog.

United States: Libraries for All Communities

In the early US, community subscription libraries, mercantile libraries (for trade groups), and athenaeum libraries (combining libraries, art galleries, and museums) grew. The Boston Athenæum and Redwood Library and Athenaeum are examples.

Americans believed that independent thought, democracy, and morality needed access to information and reading. As the country grew, libraries followed. Public education also expanded, increasing the need for books in communities. The American School Library, a 50-book set, was published in 1839 to provide essential education.

The first wholly tax-supported public library in the US was in Peterborough, New Hampshire (1833). It was funded by a town meeting and state funds. Reverend Abiel Abbot proposed it as a central collection owned by the people and free to all. New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law allowing towns to raise money for libraries in 1849.

The year 1876 was important for libraries in the US. The American Library Association was formed, The American Library Journal was founded, and Melvil Dewey published his Dewey Decimal Classification system. After the Civil War, many public libraries were started, often led by women's clubs. They donated books, raised money, and lobbied for financial support. They helped establish 75-80% of libraries across the country.

Philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie also helped build many public libraries. Carnegie, who made his money in steel, gave away much of his fortune. He built over 2,000 libraries in the US and 660 Carnegie Libraries in Britain. Carnegie required communities to provide land and governments to pay staff and maintain the libraries. This ensured libraries were part of the community and received ongoing funding.

In 1997, Bill and Melinda Gates started the U.S. Library Program. It gave grants to over 5,800 libraries, providing computers and internet access, especially in low-income communities.

Segregation in Libraries: A Difficult Past

In the southern United States, public libraries followed Jim Crow laws, separating services for white and non-white patrons. Sometimes, black individuals were not allowed to enter at all.

Desegregation during the civil rights movement was a challenging time for librarians. Libraries in the North and South had very different experiences. In the South, some industries wanted low literacy rates to ensure cheap labor. Libraries for black people often relied on fundraising efforts by black citizens. Funds were often unequal; for example, a branch for black patrons in Birmingham received only 8% of the library's budget, even though black people made up 40% of the population.

African American Libraries and Literary Societies

African Americans have a rich history with libraries. The first library started by and for African Americans in the US was the Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons (1833). It had 600 books by 1838.

The 19th century saw many African American literary societies. These societies provided libraries to their members, often through subscriptions. They were vital for black Americans to access books when they were excluded from white societies. Examples include the Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Banneker Institute. Black women also formed societies, like the Female Literary Association (1831), which had a librarian role.

Andrew Carnegie's philanthropy greatly helped "Colored Library Associations" get funding to build libraries. In the South, some black public libraries had independent governance. The first public library for African Americans in the South funded by Carnegie was the Western Colored Branch in Louisville, Kentucky (1908).

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal," also funded libraries, especially in African American communities in the South. The WPA's library project aimed to develop libraries in underserved areas and create jobs. By 1939, the WPA funded 29 segregated libraries, most of which employed African Americans.

Disaster Recovery: Libraries as Community Hubs

The US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now sees libraries as essential community services. Libraries can get emergency funding after disasters to restore services quickly. They provide internet, air conditioning, charging stations, and water access.

20th Century Libraries: Modern Design

In the 20th century, many public libraries were built in modern architectural styles. The quality of the interior spaces, with good lighting and atmosphere, became more important than just the outside look. Modern architects like Alvar Aalto focused on making library spaces comfortable and easy to use. His Municipal Library in Wolfsburg, Germany (1958–62), has a large central room with special skylights to bring in natural light.

21st Century Libraries: Digital and Community Spaces

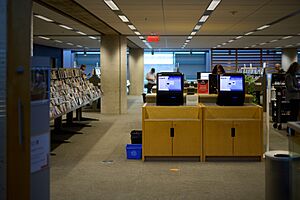

In the 21st century, libraries continue to change with new ways people read books and use media. The 21st-century library is increasingly a digital library. By 2017, all US libraries offered internet access, and 90% helped people with internet skills. Librarians now manage both physical and digital collections. Digital collections include online resources and scanned physical documents.

With more demand for digital resources, libraries worldwide have expanded their digital offerings. Ebook and audiobook use in libraries reached a record high in 2018, with 326 million loans. Libraries like the Toronto Public Library and the National Library Board of Singapore are leaders in providing digital books.

Digital libraries bring new challenges, like how to distribute resources, user authentication, and device compatibility. Initially, there was concern that ebooks might reduce community feeling in libraries. However, technology has actually increased community use, as people visit libraries more often to access these resources. Libraries also had to negotiate lower license fees for ebooks.

Libraries now offer other digital resources that attract patrons beyond books. Makerspaces (also called Hackerspaces) are a new trend. They are spaces for creativity where users can tinker, invent, and socialize. Makerspaces often have advanced technology like 3D printing or Virtual reality, making them available to people who might not otherwise have access. Many also have video and audio recording studios.

A common challenge for 21st-century libraries is budget cuts. This forces librarians to manage funds efficiently and advocate for their libraries. Libraries are adapting by providing digital services at home and creating more user-friendly spaces.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed how libraries operated. Many libraries moved to online-only resources like ebook lending. Book returns were delayed, and books were sometimes quarantined before being handled by staff. In 2021, the "Ocean Sea Public Library," the largest library in Asia, was announced to open in Hong Kong, with a museum connected to it.

Images for kids

-

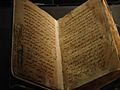

Qur'an manuscript on display at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |