Jōmon period facts for kids

|

|---|

|

The Jōmon period (Japanese: 縄文 時代, Hepburn: Jōmon jidai) was a very long time in Japanese history, lasting from about 14,000 to 300 BCE. During this period, Japan was home to the Jōmon people. These people were mostly hunter-gatherers, but they also started some early farming. They shared a common culture and lived in settled communities.

The Jōmon people created many interesting things. They made tools and jewelry from bone, stone, shells, and antlers. They also crafted beautiful pottery figurines and vessels, as well as lacquerware. Jōmon pottery is famous for its unique decorations, made by pressing cords into the wet clay. Similar cultures, where complex societies grew from hunting and gathering, also existed in places like the North American Pacific Northwest and the Valdivia culture in Ecuador.

Contents

Understanding the Jōmon Period

The Jōmon period lasted for about 14,000 years. Scientists divide this long time into several shorter phases: Incipient (13,750–8,500 BCE), Initial (8,500–5,000 BCE), Early (5,000–3,520 BCE), Middle (3,520–2,470 BCE), Late (2,470–1,250 BCE), and Final (1,250–500 BCE). Even though it all has the same name, there were many differences across regions and over time. For example, the time between the earliest Jōmon pottery and the well-known Middle Jōmon period is twice as long as the time from the building of the Great Pyramid of Giza to today.

Scientists figure out the dates for these phases mainly by looking at the styles of Jōmon pottery. They also use radiocarbon dating, a special method to find the age of ancient materials. Recent discoveries have helped refine the end date of the Jōmon period to 300 BCE. The next period, called the Yayoi period, began between 500 and 300 BCE.

It's important to know that the Jōmon period didn't apply to all parts of Japan in the same way. For example, in Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands, people often use the term Shellmidden Period instead. In Hokkaido and northern Tohoku, the Jōmon people were later joined by related groups, leading to the Zoku-Jōmon Period.

Who Were the Jōmon People?

The Jōmon people were diverse. Their ancestors came from different parts of Asia, including Northeast Asia, the Korean Peninsula, China, and Southeast Asia. Studies of ancient remains and genetics show that Jōmon people were related to other East Asians.

Modern Japanese people have ancestors from both the ancient Jōmon hunter-gatherers and the later Yayoi farmers. These two main groups arrived in Japan at different times and from different places. Scientists believe that about 30% of the male ancestry in modern Japanese people comes from the Jōmon. This shows how important the Jōmon people were in shaping Japan's population.

Scientists like Mitsuru Sakiya suggest that the Jōmon people were a mix of several very old populations. Studies also show that the Jōmon population in Hokkaido was made up of two distinct groups that later combined to form the ancestors of the Ainu people. This means the Jōmon people were more varied than once thought.

The Jōmon people came from different ancient groups who moved into Japan over many years. This means the Jōmon culture was shared by various peoples. Modern Japanese people are descended from three main groups: hunter-gatherers from the Jōmon era (around 15,000 BCE), farmers who arrived around 900 BCE (leading to the Yayoi period), and people who came during the Kofun period (300-700 CE).

Some studies have found unique genetic traits in certain Ainu individuals, who are largely descended from Hokkaido Jōmon groups. These traits are usually seen in Europeans but not other East Asians. This suggests that some people from an unknown source joined the Jōmon population in Hokkaido. However, other studies suggest that Jōmon people across Japan looked quite similar.

Recent detailed genetic studies in 2020 and 2021 gave us more information. They show that different groups mixed in Japan even during the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age). There was also a steady flow of people from coastal East Asia. This led to a diverse population that became more similar over time, until the arrival of the Yayoi people. Some Jōmon ancestors came from Northeast Asia, and others from the Tibetan Plateau and Southern China. There was also movement of people from Siberia into northern Hokkaido.

Archaeological findings suggest links between southern Jōmon culture (in Kyushu, Shikoku, and parts of Honshu) and cultures in southern China and Northeast India. These areas shared a "broadleaf evergreen forest culture," which included growing Azuki beans.

Some experts believe that the Japonic languages (the family of languages that includes Japanese) were already present in Japan and coastal Korea before the Yayoi period. They might have been spoken by some Jōmon groups in southwestern Japan. Later, during the Yayoi period, Japonic speakers expanded, adopting rice farming and mixing new technologies with local traditions.

There is also evidence that Austronesian peoples (who speak languages found in Southeast Asia and the Pacific) were in Japan during the Jōmon period. They arrived before the Yayoi migrants and were later absorbed into the Japanese population. Some words in modern Japanese might even come from unknown Jōmon languages that are now extinct.

Life in Early Jōmon Times

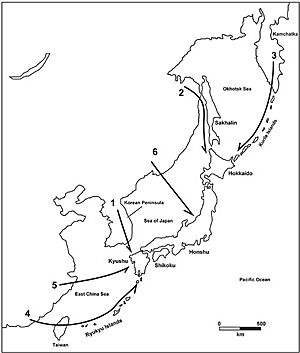

The earliest "Incipient Jōmon" phase began when Japan was still connected to mainland Asia by a narrow strip of land. Around 12,000 BCE, as the glaciers melted after the last ice age, sea levels rose. This separated the Japanese archipelago from the Asian mainland. The closest point to the Korean Peninsula (in Kyushu) was about 190 kilometers away. This distance allowed the people on the Japanese islands to develop their own unique culture.

After the Ice Age, the plants in Japan changed. In southwestern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, forests were full of broadleaf evergreen trees. In northeastern Honshu and southern Hokkaido, there were broadleaf deciduous trees and conifers. Many native trees, like beeches, buckeyes, chestnuts, and oaks, produced edible nuts and acorns. These were important food sources for both people and animals. People stored these nuts, especially in eastern Japan, in underground pits for winter.

In the northeast, the cold Oyashio Current brought a lot of marine life, especially salmon, which was another major food source. People living along both the Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean ate huge amounts of shellfish. They left behind large mounds of discarded shells and other trash, called middens. These middens are very valuable for archaeologists today. Other important foods included Sika deer, wild boar, wild plants like yam-like tubers, and freshwater fish.

Growing Communities and Early Farming

The Early Jōmon period saw a big increase in population. This is shown by the many large villages from this time. This period happened during a time when the local climate became warmer and more humid.

Early agriculture

Scientists still discuss how much farming the Jōmon people did. It's not clear if they were only hunter-gatherers. There is evidence that they cared for groves of lacquer and chestnut trees. They also grew plants like soybeans, bottle gourds, hemp, Perilla, and adzuki beans. These activities suggest they were somewhere between pure hunter-gatherers and full-time farmers.

An early type of domesticated peach appeared at Jōmon sites between 4700 and 4400 BCE. This peach was already similar to modern cultivated types. It seems this domesticated peach came to Japan from China.

A study of the adzuki bean's genes showed that all modern adzuki beans came from wild adzuki plants in eastern Japan, around 3000–5000 years ago. The changes that made them domesticated also started in Japan. These changes began to appear and increase in frequency around 10,000 years ago. This suggests that people were selecting for domesticated traits much earlier than we see clear signs of large-scale farming.

Middle Jōmon: Art and Homes

During the Middle Jōmon period, people created highly decorated pottery figurines called dogū and vessels, some with famous "flame style" designs. They also made beautiful lacquered wood objects. While pottery decoration became more complex, the clay itself remained quite rough. During this time, magatama (curved stone beads) changed from being common jewelry to important items buried with the dead. This period also saw large burial mounds and monuments.

Homes became more complex during this time. The most common type of house was a pit-house, which was partly dug into the ground. Some even had paved stone floors. A 2015 study found that these types of homes continued to be used by later cultures. This phase was the warmest of all the Jōmon periods. Towards the end, the climate started to cool down.

Later Jōmon: Changes and New Arrivals

After 1500 BCE, the climate became cooler, entering a period of neoglaciation (a time of glacier growth). The number of people living in Japan seemed to drop a lot. Fewer archaeological sites are found from after 1500 BCE.

The Japanese chestnut tree became very important. Not only did it provide nuts, but its wood was also very strong in wet conditions. It became the most used wood for building houses during the Late Jōmon phase.

During the Final Jōmon period, changes began in western Japan. People had more and more contact with the Korean Peninsula. This led to Korean-style settlements appearing in western Kyushu around 900 BCE. These new settlers brought new technologies, like wet rice farming and working with bronze and iron. They also brought new pottery styles, similar to those from the Mumun pottery period. These new settlements seemed to live alongside Jōmon and Yayoi communities for about a thousand years.

Outside of Hokkaido, the Final Jōmon period was followed by a new farming culture, the Yayoi period (around 300 BCE – 300 CE). This period is named after an archaeological site near Tokyo. In Hokkaido, the Jōmon period was followed by the Okhotsk culture and the Zoku-Jōmon (post-Jōmon) or Epi-Jōmon culture. These cultures later replaced or mixed with the Satsumon culture around the 7th century.

Population decline

At the end of the Jōmon period, the number of people living in Japan dropped sharply. Scientists think this might have been caused by food shortages and other environmental problems. They found that not all Jōmon groups suffered, but the overall population decreased. Studies of human remains show that these deaths were not caused by large-scale wars or violence.

Amazing Jōmon Pottery

The earliest pottery in Japan was made at or before the start of the Incipient Jōmon period. Jōmon hunter-gatherers created the world’s oldest known ceramics around 14,500 BCE. Small pieces of pottery, dated to 14,500 BCE, were found at the Odai Yamamoto I site in 1998. Pottery of similar age was later found at other sites like Kamikuroiwa and the Fukui cave.

The name "cord-marked" was first used by Edward S. Morse, an American zoologist. He discovered pieces of pottery in 1877 and translated "straw-rope pattern" into Japanese as Jōmon. This pottery style, decorated by pressing cords into wet clay, is considered among the oldest in the world. It has been found at many sites. Archaeologists have identified about 70 different styles of Jōmon pottery, with even more local variations.

Scientists used radiocarbon dating after World War II to confirm how old Jōmon pottery was. The earliest pots were mostly small, round-bottomed bowls, about 10-50 cm high. People likely used them for boiling food and perhaps storing it. Since these early people were hunter-gatherers, the small size might have made the pots easier to carry. As people settled down more, later bowls became larger. These pottery styles continued to develop, with more detailed decorations, wavy rims, and flat bottoms so they could stand easily.

Making pottery usually means people are living in one place, or are at least semi-settled. Pottery is heavy, bulky, and fragile, so it's not good for people who move around all the time. It seems that the Japanese islands had so much food that they could support fairly large, semi-settled populations. The Jōmon people used chipped stone tools, ground stone tools, traps, and bows. They also made tools and jewelry from bone, stone, shells, and antlers. They were skilled at fishing in both coastal and deep waters.

Ancient Stories and Modern Connections

The ancient stories about the origins of Japanese civilization go back to times that are now part of the Jōmon period. However, these stories, like those in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki (written much later, from the 6th to 8th centuries CE), don't match what archaeologists have found about Jōmon culture. For example, the traditional founding date of Japan by Emperor Jimmu is February 11, 660 BCE.

Some parts of modern Japanese culture might have come from the Jōmon period. These include early forms of Shinto religion, certain architectural styles, and technologies like lacquerware, laminated bows called yumi, and early metalworking. These influences show a mix of ideas from northern Asia, the southern Pacific, and the local Jōmon people.

Today, people's view of Jōmon culture has changed from seeing it as primitive to finding it fascinating:

- In the early 21st century, Jōmon cord marking patterns were used again in clothing, accessories, and even tattoos.

- In the 1970s, a movement began to recreate ancient Jōmon pottery using old techniques, like firing in a bonfire.

- Jōmon artifact designs inspire modern items like vessels, origami, cookies, candies, notebooks, and neckties.

- A Jōmon exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum in 2018 attracted 350,000 visitors, much more than expected.

- Jōmon-style pit houses have been rebuilt in places like the Jōmon Village Historic Garden.

- Magazines like Jōmonzine cover this prehistoric period, showing its lasting appeal.

Learn More About Japan's Past

- Comb Ceramic

- Genetic and anthropometric studies on Japanese people

- History of Japan

- Jade

- Unofficial nengō system (私年号)

- Japanese Paleolithic

- Ko-Shintō

- Prehistoric Asia

- Proto-Japonic language

- Shellmidden Period

See also

In Spanish: Período Jōmon para niños

In Spanish: Período Jōmon para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |