Humpback whale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Humpback whale |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

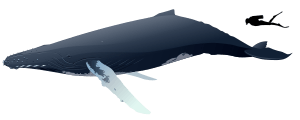

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Megaptera

|

| Species: |

novaeangliae

|

|

|

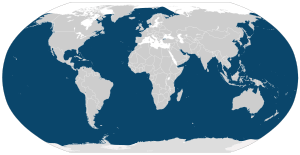

| Humpback whale range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

A humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a very large baleen whale. It has long flippers and a bumpy head. You can find these amazing creatures in every ocean around the world.

Humpback whales can grow to be about 15–16 meters (49–52 feet) long. They can weigh as much as 40 metric tons. That's like eight large elephants!

Contents

About Humpback Whales

Humpbacks are easy to spot because of their strong bodies and a clear hump on their back. They are black on top and have very long pectoral fins (side fins). Their head and lower jaw have special bumps called tubercles. These bumps are actually hair follicles and are unique to humpbacks. When a humpback dives, its tail fin often rises out of the water. The edges of its tail are wavy.

Inside their mouths, humpbacks have 270 to 400 dark baleen plates on each side. These plates are like giant combs. They help the whale filter small food from the water. The plates are about 18 inches (45 cm) long at the front and up to 3 feet (0.9 m) long at the back.

Humpbacks also have grooves on their underside, from their jaw to their belly button. These grooves are wide and help the whale's throat expand when it eats.

Female humpbacks have a round bump about 15 cm (6 inches) wide near their tail. This helps tell males and females apart.

How Big Are Humpback Whales?

Adult male humpbacks are usually about 13–14 meters (43–46 feet) long. Females are a bit bigger, around 15–16 meters (49–52 feet) long. One very large female was recorded at 19 meters (62 feet) long! Her pectoral fins were each 6 meters (20 feet) long.

Most humpbacks weigh between 25–30 metric tons. Some very big ones can weigh over 40 metric tons.

When a baby humpback whale is born, it's about the length of its mother's head. Newborn calves are about 6 meters (20 feet) long and weigh 2 metric tons. They drink their mother's milk for about six months. After that, they start eating on their own but might still drink milk for a few more months. Humpback milk is very rich, with 50% fat, and it's pink!

Female humpbacks can start having babies when they are five years old. Males become ready to mate around seven years old.

Humpback Fins

The humpback's long black and white tail fin can be up to one-third the length of its whole body. Their pectoral fins are the longest of any whale or dolphin. Scientists think these long fins help humpbacks move easily in the water. They might also help the whales control their body temperature when they travel between warm and cold places.

Identifying Individual Whales

Each humpback whale has unique patterns on its tail flukes (the two halves of its tail). These patterns are like fingerprints for humans. Scientists use photos of these tail patterns to tell individual whales apart.

One study from 1973 to 1998 used this method to learn about whales in the North Atlantic. It helped researchers understand how long whales are pregnant, how fast they grow, and when they have babies. This also helped them guess how many whales there are. Many similar photo projects are happening all over the world.

-

Humpback whale skeleton on display at The Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

-

Identifying whales in Vava'u, Tonga

-

Humpback whale skeleton of "Snow" at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

Humpback Behavior

Humpback whales can live for 45 to 100 years.

Social Interactions

Humpbacks usually live alone or in small groups that don't stay together for long. These groups often break up after a few hours. In the summer, groups might stay together longer to hunt and eat together. It's rare to see humpbacks stay together for months or years. Some female whales might keep bonds they made while feeding together for their whole lives.

Humpback whales often jump out of the water, which is called "breaching." They also slap the water with their fins or tails.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Humpback whales find partners during the winter months. This happens after they travel from their summer feeding grounds near the poles to warmer waters closer to the equator. Males often compete fiercely for females. Several males might gather around one female and fight to mate with her. They might breach, spyhop (stick their head out of the water), slap their tails or fins, or charge at each other.

The special songs that male whales sing are thought to be important for attracting females. However, other males also come closer to a singing whale, which can lead to fights. So, singing might also be a way for males to challenge each other.

Female humpbacks usually have a baby every two or three years. They are pregnant for about 11.5 months. Most babies are born in January or February in the northern hemisphere, and in July or August in the southern hemisphere.

Interactions with Other Animals

Humpbacks are friendly whales and sometimes interact with other ocean animals, like bottlenose dolphins and Right whales. These interactions have been seen in all oceans.

Scientists have even seen humpback whales protecting other animals, like seals and other whales, from killer whales. This protective behavior seems to happen all over the world. In one amazing event in 2017, two humpback whales protected a human snorkeler from a large tiger shark in the Cook Islands. One whale pushed the woman away, while the other used its tail to block the shark. This might be the first time humpbacks have been seen protecting a human!

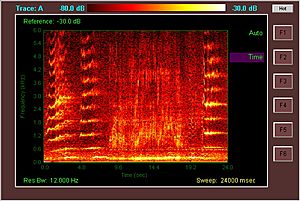

Humpback Whale Song

Both male and female humpback whales make sounds, but only males sing the long, loud, and complex "song" they are famous for. Each song has many low sounds that change in how loud they are and how high or low they sound. A song usually lasts 10 to 20 minutes. Some whales can sing for more than 24 hours straight! Whales don't have vocal cords like humans. They make sound using a special structure in their throat. They don't even need to breathe out to make sounds.

All the whales in a large area will sing the same song. For example, all humpbacks in the North Atlantic sing one song, while those in the North Pacific sing a different one. Each group's song slowly changes over many years and never repeats.

Scientists are not completely sure why whales sing. Since only males sing, one idea is that it's to attract females. But other males often come close to a singer, which can lead to a fight. So, singing might also be a way to challenge other males. Some scientists also think the song might help whales find things using sound, like echolocation.

When humpbacks are feeding, they make different sounds, not songs. These sounds help them gather fish into their "bubble nets." Humpbacks also make other noises to talk to each other, like grunts, groans, snorts, and barks.

How Humpbacks Breathe

Whales are mammals that breathe air. They must come to the surface to get air. When a humpback surfaces, you can see its small dorsal fin right after it blows air out of its blowhole. The blow (exhalation) is about 3 meters (10 feet) high and looks like a heart or a bushy cloud.

Humpbacks don't usually sleep at the surface. They need to keep breathing, so it's thought that only half of their brain sleeps at a time. This way, one half can make sure the whale surfaces to breathe without waking up the other half.

Where Humpbacks Live

Humpback whales live in all the main oceans. They are found from the edge of the Antarctic ice to as far north as 77° N latitude. There are four main groups of humpbacks: North Pacific, Atlantic, Southern Ocean, and Indian Ocean. These groups are usually separate.

Even though humpbacks live all over the world, they usually don't cross the equator. However, some observations suggest that whales from both hemispheres might meet near Cape Verde. Some humpbacks also stay in certain areas all year, like near British and Norwegian waters.

Humpbacks were once rare in the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea. But as their numbers have grown, they are now seen more often in these waters. They are also returning to places they haven't been seen in decades, like Scotland and fjords in Scandinavia.

In the North Atlantic, humpbacks feed from Scandinavia to New England. They have their babies in the Caribbean and near Cape Verde. In the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, they might have babies off Brazil and along the coasts of Africa, including Madagascar.

A large group of humpbacks gathers around the Hawaiian Islands every winter. These whales feed in areas from California to the Bering Sea.

In 2007, scientists found seven humpbacks off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica that had traveled from the Antarctic. This journey was about 8,300 kilometers (5,157 miles)! This is the longest migration ever recorded for a mammal. In Australia, there are two main groups that migrate, one off the west coast and one off the east coast.

In Panama and Costa Rica, humpback whales arrive from both the Southern Hemisphere (July–October) and the Northern Hemisphere (December–March). Populations in the South Pacific, like those near New Zealand and Tasmania, are growing.

Some humpbacks are returning to old habitats, especially in the North and South Atlantic (like the English and Irish coasts). They are also returning to parts of Asia, like the Philippines and Japan. Since 2015, whales have been gathering near Hachijō-jima in Japan. This makes it the northernmost place where humpbacks are known to have their babies.

Arabian Sea Humpbacks

There's a special group of humpback whales in the Arabian Sea that doesn't migrate. They stay there all year. Most humpbacks travel up to 25,000 kilometers (15,500 miles) each year, making them one of the most well-traveled mammals. But the Arabian Sea group is very isolated and is the most endangered, with possibly fewer than 100 animals left.

Humpbacks used to be common in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Aden. Now, more whales are being seen there, even with mothers and babies. It's not known if whales seen in the Red Sea are from this group, but sightings have increased since 2006.

What Humpbacks Eat

Humpbacks mainly eat in the summer and live off the fat they stored during winter. They rarely eat in their warm winter waters. Humpbacks are active hunters. They eat krill (tiny shrimp-like animals) and small schooling fish. This includes young salmon, herring, capelin, and sand lance. In the North Atlantic, they also eat Atlantic mackerel, pollock, and haddock. They have even been seen eating salmon fry released from fish farms in Alaska.

Humpbacks hunt by directly attacking their prey or by stunning them. They do this by hitting the water with their pectoral fins or tails.

Bubble Net Feeding

Humpbacks have the most varied ways of hunting among all baleen whales. Their most clever method is called bubble net feeding. A group of whales swims in a shrinking circle, blowing bubbles below a school of fish. The bubbles form a shrinking ring that traps the fish in a smaller and smaller space. This ring can start as wide as 30 meters (100 feet) and involve up to a dozen whales working together.

Scientists used cameras attached to whales' backs to study this. They found that some whales blow the bubbles, some dive deeper to push the fish towards the surface, and others use sounds to herd the fish into the net. Then, the whales suddenly swim upward through the "net" with their mouths wide open. They swallow thousands of fish in one gulp! The pleated grooves in their mouths help them drain the water, leaving only the fish.

Another feeding method seen in the North Atlantic is called lobtail feeding. The whale slaps the ocean surface with its tail one to four times before making the bubble net. Studies suggest that whales learn this behavior from other whales in their group.

Killer Whale Attacks

Scars on humpbacks show that killer whales (orcas) can attack young humpbacks. Until recently, no one had seen these attacks happen, and it was thought they were only minor. However, a 2014 study off Western Australia saw that when there are many young humpbacks, orcas can attack and sometimes kill them. Mothers and other adult humpbacks will protect baby whales from these attacks. It's thought that when humpbacks were nearly extinct from whaling, orcas started hunting other prey. Now that humpback numbers are growing, orcas might be going back to hunting them. There is also evidence that humpbacks will defend against or attack killer whales that are attacking either humpback calves or other species.

Humpbacks and Humans

Whaling History

Humpback whales were hunted as early as the 18th century. By the 19th century, many countries, especially the United States, hunted them heavily in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. In the late 1800s, the invention of the explosive harpoon made whaling much faster. This, along with hunting in the Antarctic Ocean starting in 1904, greatly reduced whale populations. In the 20th century, over 200,000 humpbacks were caught. This reduced the global population by more than 90%. North Atlantic populations dropped to as few as 700 whales.

The Ban on Whaling

In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was created to manage whaling. They set rules and hunting seasons. To stop humpbacks from becoming extinct, the IWC banned commercial humpback whaling in 1966. By then, there were only about 5,000 humpbacks left in the world. This ban is still in place today.

Before commercial whaling, there might have been as many as 125,000 humpbacks. The Soviet Union secretly caught many more whales than they reported. They said they caught 2,820 humpbacks between 1947 and 1972, but the real number was over 48,000!

As of 2004, only a few humpbacks are hunted each year off the Caribbean island of Bequia in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. This small hunt is not thought to harm the local whale population. Japan had planned to hunt 50 humpbacks for research in 2007/08. This caused protests around the world. Japan later agreed not to hunt humpbacks for two years to try and reach an agreement with other countries.

In 2010, the IWC allowed Greenland's native people to hunt a few humpback whales for three years. In Japan, some humpbacks are still illegally caught. Their meat can sometimes be found in markets.

Whale Watching

Whale watching is a fun activity where people observe humpbacks in the wild. People watch from the shore or from special touring boats. Humpbacks are usually curious about boats. Some whales, called "friendlies," will come very close to whale-watching boats. They might stay under or near the boat for many minutes.

Because humpbacks are often easy to approach, curious, and show many interesting behaviors, they have become a main attraction for whale tourism worldwide. Hawaii has used "ecotourism" to benefit from these whales without harming them. This business brings in $20 million each year for Hawaii's economy.

Images for kids

-

Humpback whales taken by whalers off Vancouver Island, early 20th century

-

A dead humpback washed up near Big Sur, California

-

Professor John Struthers about to dissect the Tay Whale, Dundee, photographed by George Washington Wilson in 1884

-

Possible Migaloo sighted off the Royal National Park

See also

In Spanish: Ballena jorobada para niños

In Spanish: Ballena jorobada para niños