New England town facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Town |

|

|---|---|

| Also known as: New England town |

|

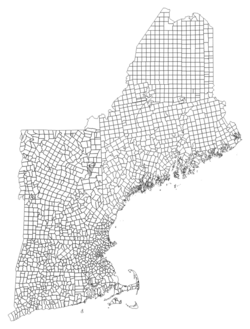

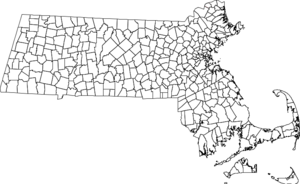

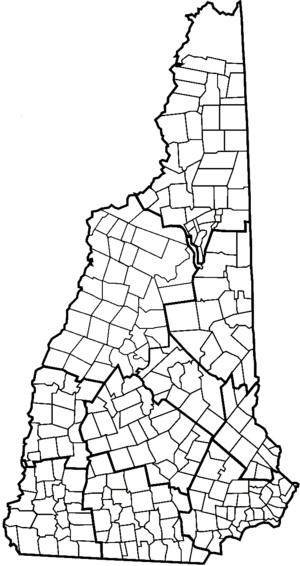

| This map shows the six New England states and their local political subdivisions. | |

| Category | Municipality |

| Location | New England |

| Found in | County |

| Created by | Various colonial agreements followed by state constitutions |

| Created | 1620 (Plymouth) |

| Number | 1,360 |

| Populations | 29 (Frenchboro) – 64,083 (West Hartford) |

| Areas | 0.8 sq mi. (New Castle) – 281.3 sq mi. (Pittsburg) |

| Government | Town meeting Select Board |

| Subdivisions | Village Neighborhood |

In the six New England states (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island), a town is the main way local government works. Unlike most other U.S. states, where counties often handle many services, New England towns are very powerful. They act like both cities and counties in other parts of the country.

New England towns cover almost all the land in these states. This means that if you leave one town, you immediately enter another town or city. Many towns are run by a town meeting, where all eligible residents can gather to make decisions. This is a form of direct democracy, like in some parts of Switzerland.

In New England, county governments are usually not very strong. In some states, like Connecticut and Rhode Island, county governments don't even exist anymore. Counties mainly serve as boundaries for courts and some state services.

Contents

What Makes a New England Town Special?

New England towns have some unique features that make them different from local governments elsewhere:

- Everywhere is a Town: Almost all land in New England is part of a town or other local government. There are very few places that are not part of a town.

- Strong Local Power: Towns are like mini-governments with a lot of power to manage their own affairs. They can make many decisions for their residents, similar to how cities operate in other states.

- Direct Democracy: Many towns use a town meeting system. This means citizens can directly vote on local laws and budgets. A group called the board of selectmen usually handles the day-to-day running of the town.

- Town Centers: A town almost always has a main developed area, often called the "town center." This center usually has the same name as the town. You might also find other smaller communities or neighborhoods within a town.

- No Gaps: When you travel in New England, you're always in a town or city. There are no empty spaces between them. Towns often have unique shapes and sizes, not like a perfect grid.

- Local Services: Most local services, like schools, police, and fire departments, are managed by the town government. County governments provide very few services, especially in the southern New England states.

- Community Identity: People in New England often feel a strong connection to their town. They see the whole town as one community.

- Towns are Common: Over 90% of local governments in New England are called "towns." Even cities in New England often started as towns and work in a similar way.

How New England Towns Developed

New England towns have a long history, going all the way back to the first English settlers. They were created even before counties in the region. As more people settled, new areas were organized into towns.

In the early days, towns were often connected to local churches. By the 1700s, colonial governments started to officially set up new towns. The town meeting style of government became common, and many towns still use it today.

Originally, towns were the only type of local government in New England. Even big cities like Boston were towns for their first 200 years!

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, almost all the land in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts was divided into towns. Maine took a bit longer, but by the end of the 1800s, most settled areas there were also towns.

In Vermont and much of New Hampshire, towns were sometimes "chartered" (officially created) even before anyone moved there. This was common in the 1700s. Once enough people arrived, they would simply start their town government.

Many early towns were very large. As they grew, new towns were often created by splitting off parts of existing towns. This happened a lot in the 1700s and 1800s. Today, it's very rare for new towns to be formed this way.

Other Types of Local Governments in New England

While towns are the main type, New England also has cities and a few other special types of local governments.

Cities

Every New England state has cities. However, cities are treated very much like towns under state law. The main difference is how they are governed. Most cities used to be towns that grew too big for a town meeting. So, they switched to a city government with an elected city council and a mayor or city manager.

People in New England often just call all local communities "towns," whether they are officially cities or not. There are far fewer cities than towns. Cities are more common in the southern, more populated states.

Cities in New England are quite old, with some dating back to the late 1700s. However, they didn't become widespread until the 1800s. Boston became a city in 1822.

In most of New England, a community's population doesn't decide if it's a city or a town. A town can sometimes have more people than a nearby city! However, in Massachusetts, a town usually needs at least 10,000 people to become a city.

Over time, the differences between towns and cities have become less clear. Many towns have adopted forms of government that are very similar to cities, even though they still call themselves "towns." For example, 13 communities in Massachusetts legally function as cities but still use the name "town."

Plantations in Maine

Besides towns and cities, Maine has a special type of community called a plantation. These are like small towns that don't have enough people to need a full town government. Plantations are usually found in less populated areas. They are "organized" but not fully "incorporated" like towns. No plantation in Maine has more than about 300 residents.

The term "plantation" was also used in colonial Massachusetts for communities that were still developing before becoming full towns. Maine got the term from Massachusetts, as it was part of Massachusetts until 1820.

Boroughs and Villages

Two New England states have smaller types of local governments within towns:

- Connecticut has incorporated boroughs.

- Vermont has incorporated villages.

These boroughs and villages are still part of their larger parent town. They handle some local services within their smaller boundaries. However, they are generally less important than towns and their numbers have been decreasing. Many have chosen to become fully part of their parent town again.

The word "village" is also often used in New England to describe a distinct area within a town or city, like a town center. These informal "villages" are not separate governments. For example, the town of Barnstable, Massachusetts includes several "villages" like Hyannis. These are not separate towns but are parts of Barnstable.

Unorganized Territory

The three northern New England states (Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine) have some areas that are "unincorporated" and "unorganized." This means they are not part of any town, city, or plantation. Maine has much more of this type of land than the other two states.

These areas are usually very sparsely populated. Most have no local government at all, and some have no permanent residents. They are definitely the exception in New England.

Leftover Areas

Sometimes, when town boundaries were drawn long ago, small areas were left out. These were called "gores," "grants," "locations," or "purchases." They were often smaller than a normal town. Over time, most of these areas in more populated regions were added to nearby towns or became towns themselves. Today, a few still exist in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine.

Unorganized Townships

These are town-sized areas that were planned as "future towns" but never had enough people to start a formal town government. They are often just called "townships."

- In New Hampshire and Vermont, there are a few of these, mostly in northern counties.

- Maine has hundreds of unorganized townships, especially in its interior. Many of these were never meant to become towns.

Towns That Disappeared

Some towns in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine used to be active towns but lost their official status, usually because their population became too small. They then became "unorganized territory."

- For example, the town of Livermore, New Hampshire disincorporated in 1951 because it had almost no residents.

- In Maine, many towns and plantations have given up their local government over the years. This often happened even if they had a few hundred residents, as Maine has a system to manage these unorganized areas.

- In Massachusetts, a few towns were disincorporated in 1938 to make way for the Quabbin Reservoir. Their land was then divided among neighboring towns.

How the Census Counts New England Towns

The United States Census Bureau counts New England towns differently from how it counts local governments in most other states.

Towns and the Census

The Census Bureau calls New England towns "minor civil divisions" (MCDs). This is the same category as "civil townships" in other states. They do this because New England towns cover a whole area, not just a single developed place.

This can be confusing because New England towns are fully incorporated governments, just like cities. But the Census Bureau's way of counting means they don't call towns "incorporated places." This is just for how the Census collects and organizes its data.

The Census Bureau does recognize New England towns in one special way: it uses town boundaries (instead of county boundaries) to define metropolitan areas in New England.

Cities and the Census

The Census Bureau does classify cities in New England as "incorporated places." They do this because cities are usually more developed and easier to compare to cities in other states. Boroughs in Connecticut and incorporated villages in Vermont are also counted as incorporated places.

Again, this can be confusing. Even though New England states treat cities and towns very similarly, the Census Bureau counts them differently. This doesn't mean cities are "more incorporated" than towns. It's just how the Census organizes its information.

Census-Designated Places (CDPs)

To provide more detailed population data, the Census Bureau sometimes creates "census-designated places" (CDPs) within New England towns. These CDPs often match town centers or other villages. However, CDPs are only found within towns, not cities.

It's important to know that CDPs in New England are not separate governments. They are just areas the Census Bureau defines for data collection. Most New Englanders identify with their entire town, not just a CDP within it.

List of New England Towns

To find a list of all towns and other town-level governments in each New England state, you can check these articles:

- List of towns in Connecticut

- List of towns in Maine

- List of municipalities in Massachusetts

- List of cities and towns in New Hampshire

- List of municipalities in Rhode Island

- List of towns in Vermont

Town Statistics

Here are some interesting facts about New England towns and cities, based on the 2020 United States census data.

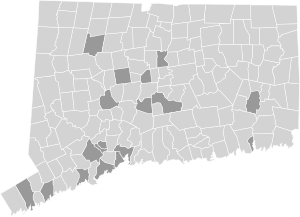

Connecticut

Connecticut has 169 official towns and cities. All of Connecticut's land is part of one of these municipalities. There are no unincorporated areas.

- The largest city by population is Bridgeport (148,654 people).

- The largest town by population is West Hartford (64,083 people).

- The smallest city by population (that is also a town) is Derby (12,325 people).

- The smallest town by population is Union (785 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is the town of New Milford (61.6 square miles).

- The smallest town-level municipality by land area is Derby (5.06 square miles).

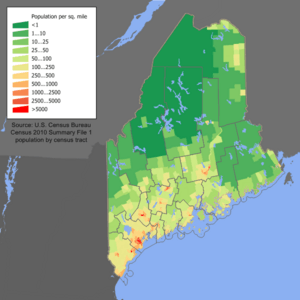

Maine

Maine has 485 organized municipalities. This includes 23 cities, 430 towns, and 32 plantations. These cover most of Maine, but some parts of the state are still unorganized.

- The largest city by population is Portland (68,408 people).

- The largest town by population is Scarborough (22,135 people).

- The smallest city by population is Eastport (1,288 people).

- The smallest town by population is Frenchboro (29 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is the town of Allagash (128.6 square miles).

- The smallest is the island plantation of Monhegan (0.85 square miles).

Massachusetts

Massachusetts has 351 municipalities, which are all cities or towns. All of Massachusetts's land is part of a municipality; there are no unincorporated areas.

- The largest city by population is Boston (675,647 people).

- The smallest city by population is Palmer (12,448 people).

- The largest town by population is Brookline (63,191 people).

- The smallest municipality overall by population is the town of Gosnold (70 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is the town of Plymouth (96.4 square miles).

- The smallest town by land area is the town of Nahant (1.08 square miles).

New Hampshire

New Hampshire has 234 incorporated towns and cities: 13 cities and 221 towns. Most of the state is covered by these, but there are some unincorporated areas in the northern part.

- The largest city by population is Manchester (115,644 people).

- The largest town by population is Derry (34,317 people).

- The smallest city by population is Franklin (8,741 people).

- The smallest incorporated municipality overall is the town of Hart's Location (68 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is the town of Pittsburg (281.3 square miles).

- The smallest is the town of New Castle (0.81 square miles).

Rhode Island

Rhode Island has 39 incorporated towns and cities: 8 cities and 31 towns. These cover the entire state; there are no unincorporated areas.

- The largest city by population is Providence (190,934 people).

- The largest town by population is Cumberland (36,405 people).

- The smallest city by population is Central Falls (22,583 people).

- The smallest overall municipality by population is the town of New Shoreham (1,410 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is Coventry (59.1 square miles).

- The smallest is Central Falls (1.19 square miles).

Vermont

Vermont has 246 incorporated towns and cities: 9 cities and 237 towns. These cover almost all of the state, but there are some unincorporated areas in mountainous regions.

- The largest city by population is Burlington (44,743 people).

- The largest town by population is Essex (22,094 people).

- The smallest city by population is Vergennes (2,553 people).

- The smallest incorporated town by population is Victory (70 people).

- The largest municipality by land area is the town of Chittenden (72.7 square miles).

- The smallest town-level municipality by land area is the city of Winooski (1.38 square miles).

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |