Origen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Origen

|

|

|---|---|

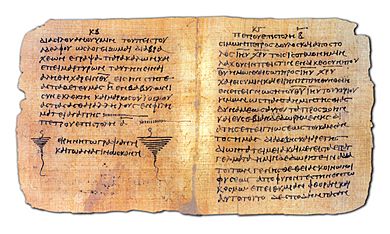

Representation of Origen writing, from a manuscript of In numeros homilia XXVII, c. 1160

|

|

| Born | c. 185 AD |

| Died | c. 253 AD (aged c. 69) Probably Tyre, Phoenice

|

| Alma mater | Catechetical School of Alexandria |

|

Notable work

|

Contra Celsum De principiis |

| Era | Ancient philosophy Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism Alexandrian school |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 – c. 253) was an important early Christian scholar and theologian. He was also known as Origen Adamantius . He was born in Alexandria, Egypt, and spent the first part of his life there.

Origen wrote about 2,000 books and papers on many religious topics. These included looking closely at Bible texts, explaining Bible meanings, and discussing spiritual ideas. He was one of the most important and talked-about people in early Christian thought. Many people called him "the greatest genius the early church ever produced."

Origen wanted to become a martyr like his father when he was young. But his mother stopped him from giving himself up to the authorities. When he was 18, Origen became a teacher at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. He studied very hard and lived a simple, strict life. Later, he had problems with Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria. This happened after Origen was made a presbyter (a type of priest) by a friend in another city.

Origen then started the Christian School of Caesarea. There, he taught logic, how the universe works, natural history, and theology. Churches in Palestine and Arabia saw him as the top expert on religious matters. In 250, he was tortured for his faith during a time when Christians were persecuted. He died a few years later from his injuries.

Origen wrote many books because his friend, Ambrose of Alexandria, helped him. Ambrose gave him a team of people to copy his works. One of Origen's most important books was On the First Principles. It explained the main ideas of Christian theology. He also wrote Contra Celsum, which defended Christianity against a pagan philosopher named Celsus. Origen also created the Hexapla, which was the first critical edition of the Hebrew Bible. It showed the original Hebrew text next to four different Greek translations. He wrote many sermons, often explaining Bible stories as symbolic.

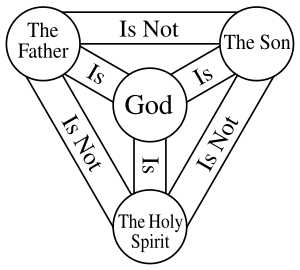

Origen taught that before God made the world, He created all intelligent beings as souls. These souls were close to God but then moved away from Him. They were then given physical bodies. Origen was also the first to fully explain the ransom theory of atonement. This idea says that Jesus's death was a payment to free humanity from evil. He also helped develop the idea of the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). Origen hoped that everyone might eventually be saved, but he said this was just his idea. He believed in free will and supported Christian pacifism, which means not fighting in wars.

Some Christian groups see Origen as a Church Father. However, Orthodox Christianity does not give him this title. He is still seen as one of the most important Christian thinkers. His ideas were very popular in the East. But arguments about his teachings led to problems, known as the Origenist crises. In 543, Emperor Justinian I ordered his writings to be burned. The Second Council of Constantinople in 553 might have officially condemned Origen. But it might have only condemned certain ideas that people thought came from him. His ideas about souls existing before birth were rejected by the Church.

Contents

Life of Origen

Early Years

Most of what we know about Origen's life comes from a book called Ecclesiastical History. It was written by a Christian historian named Eusebius around 260–340 AD. Eusebius wrote about Origen almost 50 years after Origen died. He showed Origen as a perfect Christian scholar and a saint.

Origen was born in Alexandria in 185 or 186 AD. His father, Leonides of Alexandria, was a respected teacher and a strong Christian. He was later killed for his faith. Origen's mother's name is not known. She might not have been a Roman citizen. This means Origen probably wasn't a Roman citizen either. Origen's father taught him about books, philosophy, and the Bible. Eusebius said Origen's father made him learn parts of the Bible every day. Origen became very knowledgeable about the Bible at a young age.

In 202 AD, when Origen was young, the Roman Emperor ordered Christians to be killed if they openly practiced their faith. Origen's father was arrested and put in prison. Origen wanted to give himself up too, but his mother hid his clothes to stop him. His father was killed, and the family lost everything. Origen was the oldest of nine children. It became his job to support his family.

When he was 18, Origen became a teacher at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. He lived a very simple and strict life. He taught all day and wrote at night. He walked barefoot and owned only one cloak. He ate simple food and often went without eating for long times.

A rich Gnostic woman (someone with different Christian beliefs) took Origen in. She also helped a Gnostic theologian. Origen studied in her home but did not share their religious practices. Later, Origen helped a rich man named Ambrose of Alexandria become an orthodox Christian. Ambrose was so impressed that he gave Origen a house. He also gave him secretaries and copyists. Ambrose paid for all of Origen's writings to be published.

When he was in his early twenties, Origen sold his Greek books. He used the money to keep studying the Bible and philosophy. He studied at many schools in Alexandria. He learned from Ammonius Saccas at the Platonic Academy.

Travels and Early Writings

In his early twenties, Origen became more interested in being a philosopher. He gave his teaching job to a younger colleague. Origen's new role as a Christian philosopher caused problems with Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria. Demetrius was a powerful leader. He wanted the bishop of Alexandria to have more authority. Origen's independent role challenged this.

Origen started writing his huge book, On the First Principles. This book explained Christian theology for many years to come. He also began traveling to schools around the Mediterranean Sea. In 212, he went to Rome, a big center for philosophy. In 213 or 214, the governor of Arabia asked to meet Origen. He wanted to learn about Christianity from him. Origen went to Arabia for a short time and then returned to Alexandria.

In 215, the Roman Emperor Caracalla visited Alexandria. Students protested and made fun of him. Caracalla got angry and ordered his soldiers to attack the city. He also told them to kick out all teachers and thinkers. Origen fled Alexandria and went to Caesarea Maritima in Palestine. There, the bishops Theoctistus of Caesarea and Alexander of Jerusalem admired him. They asked him to give talks about the scriptures in their churches. This meant Origen was giving sermons, even though he wasn't officially a priest. This made Demetrius very angry. He saw it as a challenge to his power. Demetrius demanded that Origen return to Alexandria. He also said it was wrong for someone not ordained to preach. The Palestinian bishops disagreed. They said Demetrius was just jealous of Origen's fame.

Origen went back to Alexandria. He brought an old scroll of the Hebrew Bible that he had bought in Jericho. This scroll was found "in a jar." It became a key text for his Hexapla. Origen studied the Old Testament deeply. Some scholars believe he even learned Hebrew.

Origen also studied the entire New Testament, especially the letters of Paul and the Gospel of John. He thought these were the most important writings. With Ambrose's help, Origen wrote the first five books of his Commentary on the Gospel of John. He also wrote commentaries on Genesis, Psalms, and Lamentations. These works contained many new ideas. This led to more disagreements with Demetrius.

Conflict and Move to Caesarea

Origen often asked Demetrius to make him a priest, but Demetrius always said no. Around 231, Demetrius sent Origen to Athens. On his way, Origen stopped in Caesarea. The bishops there, Theoctistus and Alexander, were his friends. Origen asked Theoctistus to ordain him as a priest. Theoctistus happily did so. When Demetrius heard about this, he was furious. He said Origen's ordination by a foreign bishop was an act of rebellion.

Eusebius says Origen decided to stay in Caesarea because of Demetrius's anger. The bishops in Palestine declared Origen the main theologian of Caesarea. Firmilian, a bishop from another city, admired Origen so much that he begged him to come and teach there.

Demetrius complained to other church leaders, including the church in Rome. Demetrius also claimed that Origen taught that even Satan would eventually be saved. Origen strongly denied this. This accusation likely came from a misunderstanding. Origen had argued that Satan's fate was due to his own free will, not because he was absolutely evil.

Demetrius died in 232. The accusations against Origen became less strong but did not disappear. Origen wrote a letter denying that he ever taught Satan would be saved. He said the idea was "ludicrous."

Work and Teaching in Caesarea

When Origen first arrived in Caesarea, his main goal was to start a Christian school. Caesarea was already a learning center for Jews and Greek philosophers. But it didn't have a Christian higher education center. The school Origen founded was for young non-Christians interested in Christianity. It aimed to explain Christian ideas using Middle Platonism (a type of Greek philosophy). Origen started by teaching his students Socratic reasoning. Then he taught them about the universe and natural history. Finally, he taught them theology, which he saw as the highest form of philosophy.

Origen's reputation grew greatly in Caesarea. He became known as a brilliant thinker across the Mediterranean. Church leaders in Palestine and Arabia saw him as the top expert on all religious matters. While teaching in Caesarea, Origen continued his Commentary on John. He also wrote On Prayer for his friends Ambrose and Tatiana. In this book, he looked at different types of prayers in the Bible. He also explained the Lord's Prayer in detail.

Non-Christians were also interested in Origen. The philosopher Porphyry traveled to Caesarea to hear Origen's lectures. Porphyry said Origen had studied the ideas of Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle. But Porphyry accused Origen of putting Christian scriptures above true philosophy. Eusebius also reported that Origen was asked to go to Antioch. Julia Avita Mamaea, the mother of Emperor Severus Alexander, wanted him to discuss Christian philosophy with her.

In 235, Emperor Alexander Severus, who was kind to Christians, was killed. The new Emperor, Maximinus Thrax, started persecuting those who supported his predecessor. Christian leaders were targeted. Origen went into hiding. His friend Ambrose was arrested. Origen wrote Exhortation to Martyrdom to honor them. This book is now seen as a great work of Christian resistance. After Maximinus died, Origen came out of hiding. He founded another school where Gregory Thaumaturgus was a student. Origen preached regularly, sometimes daily.

Later Life and Death

Between 238 and 244, Origen visited Athens. There, he finished his Commentary on the Book of Ezekiel. He also started writing his Commentary on the Song of Songs. He then visited Ambrose in Nicomedia. Some say Origen also met Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism.

The Christians in the eastern Mediterranean still respected Origen as a very orthodox theologian. When a bishop named Beryllus of Bostra started teaching that Jesus was only human at birth, they sent Origen to talk to him. Origen debated Beryllus in public. Beryllus was convinced and promised to teach Origen's ideas from then on. Another time, a Christian leader taught that the soul died with the body. Origen argued against this, saying the soul is immortal.

Around 249, a terrible plague began. In 250, Emperor Decius blamed Christians for the plague. He ordered them to be persecuted. This time, Origen could not escape. The governor of Caesarea ordered that Origen not be killed until he publicly gave up his Christian faith. Origen was imprisoned and tortured for two years. But he refused to give up his faith. In June 251, Decius was killed in battle. Origen was released from prison. However, his health was broken by the torture. He died less than a year later, at 69 years old. A later story says he died and was buried in Tyre.

Origen's Writings

Bible Studies

Origen was a very active writer. Some say he wrote about 6,000 works in his lifetime, though this might be too high. Jerome listed nearly 2,000 titles by Origen.

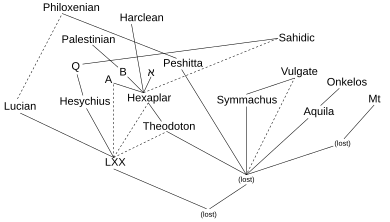

His most important work on Bible texts was the Hexapla (meaning "Sixfold"). This huge study compared different translations of the Old Testament. It had six columns: Hebrew, Hebrew in Greek letters, the Septuagint (a Greek translation), and Greek translations by Theodotion, Aquila of Sinope, and Symmachus. Origen was the first Christian scholar to add special marks to a Bible text. He used signs from the Great Library of Alexandria. For example, a passage in the Septuagint not found in the Hebrew text was marked with an asterisk (*).

The Hexapla was the main book in the Great Library of Caesarea, which Origen started. It was still important when Jerome used it centuries later. When Emperor Constantine the Great ordered 50 copies of the Bible to be made, Eusebius used the Hexapla for the Old Testament. The original Hexapla is lost, but parts of it survive. A nearly complete Syriac translation of the Greek column also exists. For some parts, like the Book of Psalms, Origen included even more Greek translations. This section was called Enneapla ("Ninefold"). Origen also made a shorter version called Tetrapla ("Fourfold"). It only had the four Greek translations.

Origen wrote many detailed notes on books like Exodus, Leviticus, Isaiah, and the Gospel of John. None of these notes have survived completely. But parts of them were used in later collections of Bible comments by Church Fathers. Origen also wrote many sermons, called homilies. There are over 200 of his homilies still existing today. They cover almost the entire Bible.

In 2012, 29 new homilies by Origen were found in a old manuscript. Experts confirmed they were real. Origen is a main source of information about the texts that later became the New Testament. He accepted books like 1 John, 1 Peter, and Jude as real. He also mentioned 2 John, 3 John, and 2 Peter, but noted that people thought these might be fake. Origen helped lay the groundwork for the idea of a Bible canon (the official list of books).

Main Commentaries

Origen's commentaries on specific Bible books focused on explaining the text in a deep way. He used careful methods, like those used by scholars in Alexandria. These writings also show his wide knowledge of many subjects. He could cross-reference words, listing every place a word appeared in the scriptures. This was amazing, as Bible concordances (word indexes) didn't exist then.

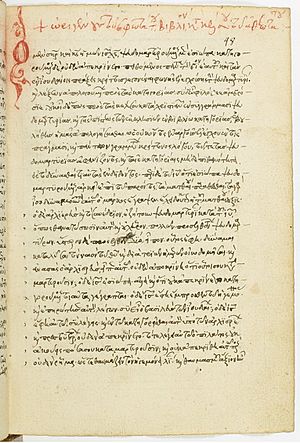

Origen's huge Commentary on the Gospel of John had over 32 volumes. He wrote it to explain the Bible correctly and to argue against the ideas of a Gnostic teacher. Only nine of the original 32 books have survived.

Of his 25 books on the Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, only eight survive in Greek. A Latin translation also exists. This commentary was seen as a classic. It helped make the Gospel of Matthew the main gospel. Origen's Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans was 15 books long. Only tiny parts of the Greek original remain. A shorter Latin translation was made by Tyrannius Rufinus in the late 300s.

Origen also wrote a Commentary on the Song of Songs. He explained why this book was important for Christians. This was his most famous commentary. Jerome said that in this work, Origen "excelled himself." Origen saw the Song of Songs as a symbolic story. The bridegroom was God's Word, and the bride was the believer's soul. This idea was very influential.

On the First Principles

Origen's On the First Principles was the first book to explain Christian theology in a systematic way. He wrote it when he was young, between 220 and 230 AD. Only parts of the original Greek text remain. Most of the book survives in a shorter Latin translation by Tyrannius Rufinus from 397 AD.

On the First Principles starts by explaining what theology is. Book One talks about the heavenly world. It describes God's oneness, the relationship between the three parts of the Trinity, and angels. Book Two describes the human world. It covers Jesus becoming human, the soul, free will, and what happens at the end of time. Book Three discusses how the universe works, sin, and salvation. Book Four explains the purpose of things and how to understand the scriptures.

Against Celsus

Against Celsus (Greek: Κατὰ Κέλσου; Latin: Contra Celsum) was Origen's last major work, written around 248 AD. It is fully preserved in Greek. This book defends orthodox Christianity against attacks from the pagan philosopher Celsus. Celsus was a major critic of early Christianity. In 178, Celsus wrote a book called On the True Word. It made many arguments against Christianity. The church first ignored Celsus. But Origen's friend Ambrose brought it to his attention. Origen decided to write a response.

In the book, Origen carefully answers each of Celsus's arguments. He argues that Christian faith has a logical basis. Origen uses ideas from Plato. He says that Christianity and Greek philosophy are not against each other. He believes philosophy has much truth, but the Bible has even greater wisdom. Celsus claimed Jesus used magic for his miracles. Origen replied that Jesus did miracles to change people, not just for show. Contra Celsum became the most important early Christian defense of the faith. Before this book, many saw Christianity as a simple religion for uneducated people. Origen's work helped Christianity gain academic respect.

Other Writings

Between 232 and 235, Origen wrote On Prayer. The full Greek text of this book has survived. It talks about why we pray and how to pray. It also explains the Lord's Prayer. On Martyrdom, or Exhortation to Martyrdom, also survives completely in Greek. He wrote it during a time of persecution. In it, Origen warns against worshipping idols. He stresses the duty of bravely suffering for faith.

In 1941, two new works by Origen were found in Egypt. One is On the Pascha (Passover). The other is Dialogue with Heracleides. This is a record of a debate between Origen and a bishop named Heracleides. Heracleides believed the Father and Son in God were the same. Origen used questions to convince Heracleides to believe in the "Logos theology." This idea says the Son (Logos) is separate from God the Father. This debate was known for being very polite and respectful.

Many of Origen's letters have been lost. Only a few fragments and three full letters remain. One letter is to his friends in Alexandria. Another is a short letter to Gregory Thaumaturgus. The third is a letter to Sextus Julius Africanus. In it, Origen defends parts of the book of Daniel.

Origen's Ideas

Christology (Ideas about Jesus)

Origen wrote that Jesus was "the firstborn of all creation." He believed Jesus had a human body and a human soul. He strongly believed Jesus was truly human. Origen saw Jesus's human nature as the one soul that stayed closest to God. This soul remained perfectly faithful. When Jesus became human, his soul joined with the Logos (God's Word). They became one. So, Origen believed Christ was both human and divine.

Origen was the first to fully explain the ransom theory of atonement. This idea says that Jesus's death on the cross was a payment to Satan. This payment freed humanity. The theory suggests that Satan was tricked by God. Jesus was without sin and was God in human form. So, Satan could not keep him enslaved. This theory was later developed by other theologians. But in the 1000s, it became less popular in Western Europe. However, it is still somewhat popular in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Cosmology and Eschatology (Ideas about the Universe and End Times)

One of Origen's main ideas was the preexistence of souls. He taught that before God made the physical world, He created many "spiritual intelligences" (souls). These souls were devoted to God. But over time, most of them grew tired of thinking about God. Their love for Him "cooled off." When God created the world, these souls were given physical bodies. Those whose love for God lessened the most became demons. Those whose love lessened moderately became human souls. Those whose love lessened the least became angels. But one soul stayed perfectly devoted to God. This soul became one with the Word (Logos) of God. The Logos later became human as Jesus Christ.

It is debated whether Origen believed in reincarnation. He clearly rejected "the false doctrine of the transmigration of souls into bodies." But this might refer to only a specific type of reincarnation. Origen did reject the idea of eternal return (the universe repeating itself exactly). But he did think there were many different worlds.

Origen believed that eventually, the whole world would become Christian. He thought the Kingdom of Heaven had not yet fully arrived. But he believed Christians should make its reality present in their lives. Origen is often seen as a Universalist. This means he suggested that all people might eventually be saved. But this would happen after their sins were cleansed by "divine fire." This fire was not literal. It was the inner pain of knowing one's own sins. Origen always said that universal salvation was just a possibility, not a definite teaching.

Ethics (Ideas about Right and Wrong)

Origen strongly believed in free will. He rejected the idea that some people were chosen for salvation and others for damnation. Origen believed that even souls without bodies could make their own choices. He used the story of Jacob and Esau to support his idea. He argued that the conditions a person is born into (rich, poor, sick, healthy) depend on what their souls did before birth. Origen said that God's knowing future events, like Judas's betrayal, does not mean people don't have free will. It just means God knows what choices they will make. Origen believed that choosing good makes you free, while choosing evil makes you a slave.

Origen was a strong pacifist. In Against Celsus, he said that Christianity's peaceful nature was very clear. He admitted some Christians served in the Roman army. But he insisted that fighting in earthly wars went against Christ's teachings. Origen believed that a Christian could not fight in a war without hurting their faith. He said Christ had forbidden all violence. Origen explained violent parts of the Old Testament as symbolic. He pointed to other Old Testament passages that he saw as supporting nonviolence. He believed that if everyone were peaceful like Christians, there would be no wars.

Hermeneutics (How to Interpret the Bible)

For who that has understanding will suppose that the first, and second, and third day, and the evening and the morning, existed without a sun, and moon, and stars? And that the first day was, as it were, also without a sky? And who is so foolish as to suppose that God, after the manner of a husbandman, planted a paradise in Eden, towards the east, and placed in it a tree of life, visible and palpable, so that one tasting of the fruit by the bodily teeth obtained life? And again, that one was a partaker of good and evil by masticating what was taken from the tree? And if God is said to walk in the paradise in the evening, and Adam to hide himself under a tree, I do not suppose that anyone doubts that these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, the history having taken place in appearance, and not literally.

Origen based his religious ideas on the Christian scriptures. He was careful not to go against what he believed the Bible said. But he did like to think beyond what was clearly stated in the Bible. This sometimes put him between accepted beliefs and ideas that were seen as wrong.

Origen believed there were two types of Bible writings: historia (history or stories) and nomothesia (laws or rules). He said the Old and New Testaments should be read together. Origen taught that Bible passages could be understood in three ways:

- The "flesh" was the literal, historical meaning.

- The "soul" was the moral lesson.

- The "spirit" was the eternal, deeper meaning.

Origen saw the "spiritual" meaning as the most important. He believed some passages had no literal meaning at all. Their meanings were purely symbolic. But he also said that "the passages which are historically true are far more numerous."

Origen noticed that the stories of Jesus's life in the four gospels had some differences. But he argued that these differences did not take away from the spiritual meanings. Origen's idea of two creations came from a symbolic reading of the Book of Genesis. The first creation (Genesis 1:26) was of pure spirits. The second creation (Genesis 2:7) was when human souls got spiritual bodies. The "tunics of skin" (Genesis 3:21) meant these spiritual bodies became physical. Each step meant a move away from the original perfect state.

Theology (Ideas about God)

Origen believed God the Father was a perfect unity. He was invisible and without a body. He was beyond all material things, so He could not be fully understood. God was also unchanging and beyond space and time. But His power was limited by His goodness, justice, and wisdom. God revealed Himself through the Logos (God's Word). The Logos was the first creation of God. It helped connect God and the world.

The Logos is the logical and creative power that fills the universe. It guides all humans towards God's truth through their ability to think. As people think more rationally, they become more like Christ. But they still keep their own unique selves. Creation happened only through the Logos.

Origen greatly helped develop the idea of the Trinity. He said the Holy Spirit was part of God. He believed the Holy Spirit lived within every person. He thought the Holy Spirit's inspiration was needed to talk about God. Origen taught that all three parts of the Trinity were needed for a person to be saved.

In some writings, Origen seemed to use the term homooúsios (meaning "of the same substance") for the Father and the Son. But it's hard to be sure if these quotes truly came from Origen. In other places, Origen rejected the idea that the Son and Father were one hypostasis (meaning one being) as wrong.

Origen was a subordinationist. This means he believed the Father was superior to the Son. And the Son was superior to the Holy Spirit. This idea came from Platonic thinking. Jerome wrote that Origen believed God the Father was invisible to everyone, even the Son and Holy Spirit. And the Son was invisible to the Holy Spirit. At one point, Origen suggested the Son was created by the Father, and the Holy Spirit by the Son. But he also wrote that he found no Bible passage saying the Holy Spirit was created. In Origen's time, the official ideas about the Trinity were not yet fully formed. Subordinationism was not yet seen as wrong. Most theologians before the Arian controversy (a big debate about Jesus's nature) were subordinationists to some degree. Origen's ideas might have come from his efforts to defend God's unity against Gnostics.

Influence on the Church

Before the Crises

Origen is often seen as the first major Christian theologian. Even though his ideas were questioned in Alexandria during his life, after his death, Pope Dionysius of Alexandria became a strong supporter of his theology. Every Christian theologian after him was influenced by his ideas. Origen's contributions were so big that his followers often focused on different parts of his teachings. Dionysius emphasized Origen's ideas about subordination. This led Dionysius to question the unity of the Trinity, causing problems in North Africa. At the same time, another follower of Origen taught that the Father and Son were "of one substance."

For centuries after his death, Origen was seen as a strong defender of accepted Christian beliefs. His philosophy greatly shaped Eastern Christianity. Origen was respected as one of the greatest Christian teachers. Monks especially loved him. They saw themselves as continuing his strict, simple lifestyle. But as time went on, Origen was judged by later standards of belief, not by the standards of his own time. In the early 300s, some writers criticized his more speculative ideas. But they agreed with him on most other points. Others, however, called him a heretic.

Both accepted and non-accepted theologians claimed to follow Origen's ideas. Athanasius of Alexandria, a key supporter of the Holy Trinity at the First Council of Nicaea, was deeply influenced by Origen. So were Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (known as the "Cappadocian Fathers"). At the same time, Origen also influenced Arius of Alexandria and his followers. Many Christians in ancient times believed Origen was the real source of the Arian heresy.

First Origenist Crisis

The First Origenist Crisis started in the late 300s. It happened as monasticism (monk life) grew in Palestine. The first problems came from Epiphanius of Salamis, a bishop from Cyprus. He wanted to get rid of all wrong beliefs. Epiphanius attacked Origen in his books. He listed ideas Origen had that Epiphanius thought were wrong. Epiphanius said Origen was a good Christian who was corrupted by "Greek education." Epiphanius especially disliked Origen's ideas about subordination. He also disliked Origen's "too much" use of symbolic Bible interpretation. And he didn't like Origen's habit of suggesting ideas as "exercises" rather than as definite teachings.

Epiphanius asked John, the bishop of Jerusalem, to condemn Origen. John refused. He said a person could not be called a heretic after they had died. In 393, a monk asked for Origen's writings to be criticized. Tyrannius Rufinus, a priest and a long-time admirer of Origen, rejected this. But Rufinus's friend Jerome, who had also studied Origen, agreed with the request. Around this time, John Cassian, a monk from the East, brought Origen's teachings to the West.

In 394, Epiphanius wrote to John of Jerusalem again. He asked him to condemn Origen. He said Origen's writings spoke badly of human reproduction. John again said no. By 395, Jerome had joined the anti-Origenists. He begged John to condemn Origen, but John still refused. Epiphanius then started a campaign against John. He openly preached that John was a follower of Origen.

In 397, Rufinus published a Latin translation of Origen's On First Principles. Rufinus believed that wrong ideas had been added to Origen's original book by heretics. So, he changed Origen's text a lot. He left out or changed parts that didn't agree with accepted Christian beliefs of his time. In his introduction, Rufinus said Jerome had studied with Origen's follower, implying Jerome was an Origenist. Jerome was so angry that he decided to make his own Latin translation. He promised to translate every word exactly. He wanted to show Origen's wrong ideas to everyone. Jerome's translation is now lost.

In 399, the crisis reached Egypt. Pope Theophilus I of Alexandria at first supported Origen. He even preached that God had no body. But a large group of monks who believed God had a human-like body protested. To stop a riot, Theophilus suddenly changed his mind. He began to speak against Origen. In 400, Theophilus held a council in Alexandria. It condemned Origen and his followers. They were called heretics for teaching that God had no body. The council said the only true belief was that God had a physical body like a human.

Theophilus called Origen the "hydra of all heresies." He convinced Pope Anastasius I to sign the council's letter. In 402, Theophilus forced Origenist monks out of Egyptian monasteries. He also banished four monk leaders. John Chrysostom, the leader of Constantinople, gave these monks a safe place. Theophilus used this to get John condemned and removed from his position in 403. After John Chrysostom was removed, Theophilus made peace with the Origenist monks in Egypt. The first Origenist crisis ended.

Second Origenist Crisis

The Second Origenist Crisis happened in the 500s. It was during a time when Byzantine monasticism (monk life) was very strong. This crisis is not as well documented as the first one. It seems to have been mostly about the ideas of Origen's later followers. Origen's follower, Evagrius Ponticus, taught about quiet, spiritual prayer. But other monks focused on strict practices like fasting and hard work.

Some Origenist monks in Palestine, called "Isochristoi" (meaning "those who would be equal to Christ"), emphasized Origen's idea of souls existing before birth. They believed all souls were originally equal to Christ's. They thought they would become equal again at the end of time. Another group of Origenists in the same area were more moderate. They believed Christ was the "leader of many brethren," as the first-created being. Both groups accused each other of wrong beliefs. Other Christians accused both of them of wrong beliefs.

The moderate group asked Emperor Justinian I to condemn the Isochristoi. In 543, Justinian received documents against Origen. These included a letter from the Patriarch of Constantinople and parts of Origen's On First Principles. A church meeting decided that the Isochristoi's teachings were wrong. They saw Origen as the cause of this problem. So, they also condemned Origen as a heretic. Emperor Justinian ordered all of Origen's writings to be burned. In the West, a document from between 519 and 553 listed Origen as an author whose writings should be banned.

In 553, at the start of the Second Council of Constantinople, the bishops condemned Origen. They said he was the leader of the Isochristoi. This letter was not part of the council's official acts. It mostly repeated the earlier condemnation from 543. It mentioned wrong ideas attributed to Origen. But these ideas were actually from Evagrius Ponticus, not Origen himself. Some experts believe Origen's name was added to the text later. Even if his name was in the original text, the ideas condemned were those of later followers. They had little to do with what Origen actually wrote.

After the Condemnations

If orthodoxy were a matter of intention, no theologian could be more orthodox than Origen, none more devoted to the cause of the Christian faith.

Because of the many condemnations, only a small part of Origen's many writings have survived. Still, these surviving texts are a large number of Greek and Latin works. Many more writings exist as fragments, quoted by later Church Fathers. It is likely that his most unusual ideas have been lost. This makes it hard to know if Origen truly held all the wrong views he was accused of.

Despite the condemnations, the church still admired Origen. He remained a key figure in Christian theology for the first thousand years. He was still seen as the founder of Bible interpretation. Anyone serious about understanding the scriptures would have known Origen's teachings.

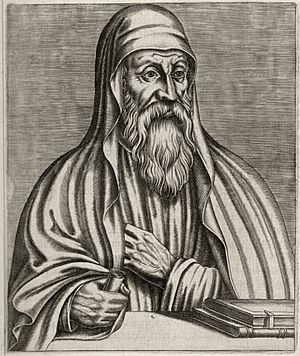

| Saint Origen the Scholar | |

|---|---|

portrait by Guillaume Chaudière (1584)

|

|

| Teacher and theologian | |

| Born | c. 185 Alexandria |

| Died | c. 253 Tyre |

| Venerated in | Evangelical Church in Germany, Anglican Communion, Reformed Tradition, Oriental Orthodox Churches |

| Feast | April 27 |

| Attributes | monastic habit |

| Controversy | Lack of formal canonization, accusations of heresy |

Jerome's Latin translations of Origen's sermons were widely read in Europe during the Middle Ages. Origen's ideas greatly influenced the Byzantine monk Maximus the Confessor and the Irish theologian John Scotus Eriugena. Since the Renaissance, the debate about Origen's accepted beliefs has continued.

Basilios Bessarion, a Greek scholar, translated Origen's Contra Celsum into Latin in 1481. In 1487, a big argument started. The Italian scholar Giovanni Pico della Mirandola said it was "more reasonable to believe that Origen was saved than he was damned." A church group condemned Pico's view because of the earlier condemnations against Origen.

The most famous supporter of Origen during the Renaissance was Desiderius Erasmus. He thought Origen was the greatest Christian writer. Erasmus said he learned more from one page of Origen than from ten pages of Augustine. Erasmus especially liked Origen's clear writing style. Erasmus used Origen's ideas about free will in his own important book, On Free Will. In the 1500s, Erasmus published the most complete edition of Origen's writings up to that time.

Origen's focus on human effort in salvation appealed to Renaissance thinkers. But it made him less popular with the leaders of the Reformation. Martin Luther thought Origen's ideas about salvation were wrong. He ordered Origen's writings to be banned. However, earlier reformer Jan Hus was inspired by Origen. He believed the church was a spiritual reality, not just an official organization. And Huldrych Zwingli, another reformer, used Origen's ideas for his symbolic interpretation of the Eucharist.

In the 1600s, the English scholar Henry More was a devoted follower of Origen. He accepted most of Origen's teachings, though he rejected universal salvation. Pope Benedict XVI admired Origen. He called him "a figure crucial to the whole development of Christian thought" and "a true 'maestro'." He also called him "not only a brilliant theologian but also an exemplary witness of the doctrine he passed on." Modern Protestant evangelicals admire Origen's strong devotion to the Bible. But they are often confused or upset by his symbolic interpretation of it. Many believe it ignores the literal truth.

Origen is often noted for not being officially recognized as a saint by all Christian groups. However, some notable people have referred to him as Saint Origen. These include Anglicans, Calvinists, and Oriental Orthodox Christians. Origen's father, Saint Leonides of Alexandria, has a feast day on April 22 in the Catholic tradition. The Evangelical Church in Germany celebrates April 27 as Origen's feast day.

Translations

- The Commentary of Origen On S. John's Gospel, the text revised and with a critical introduction and indices, A. E. Brooke (2 volumes, Cambridge University Press, 1896): Volume 1, Volume 2

- Contra Celsum, trans Henry Chadwick, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965)

- On First Principles, trans GW Butterworth, (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1973) also trans John Behr (Oxford University Press, 2019) from the Rufinus trans.

- Origen: An Exhortation to Martyrdom; Prayer; First Principles, book IV; Prologue to the Commentary on the Song of Songs; Homily XXVII on Numbers, trans R Greer, Classics of Western Spirituality, (1979)

- Origen: Homilies on Genesis and Exodus, trans RE Heine, FC 71, (1982)

- Origen: Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1–10, trans RE Heine, FC 80, (1989)

- Treatise on the Passover and Dialogue of Origen with Heraclides and his Fellow Bishops On the Father, the Son and the Soul, trans Robert Daly, ACW 54 (New York: Paulist Press, 1992)

- Origen: Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 13–32, trans RE Heine, FC 89, (1993)

- The Commentaries on Origen and Jerome on St Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians, RE Heine, OECS, (Oxford: OUP, 2002)

- The Commentary of Origen on the Gospel of St Matthew, 2 vols., trans RE Heine, OECS, (Oxford: OUP, 2018)

- Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books 1–5, 2001, Thomas P. Scheck, trans., The Fathers of the Church series, Volume 103, Catholic University of America Press, ISBN: 0-8132-0103-9 ISBN: 9780813201030

- Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books 6–10 (Fathers of the Church), 2002, The Fathers of the Church, Thomas P. Scheck, trans., Volume 104, Catholic University of America Press, ISBN: 0-8132-0104-7 ISBN: 9780813201047

- On Prayer in Tertullian, Cyprian and Origen, "On the Lord's Prayer", trans and annotated by Alistair Stewart-Sykes, (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2004), pp. 111–214

- Translations available online

- Translations of some of Origen's writings can be found in Ante-Nicene Fathers or in The Fathers of the Church. () Material not in those collections includes:

- Dialogue with Heracleides ()

- On Prayer ()

- Philocalia ()

See also

In Spanish: Orígenes para niños

In Spanish: Orígenes para niños

- Adamantius (Pseudo-Origen)

- Allegorical interpretations of Plato

- Apocatastasis

- Descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross

- Pre-existence of the soul

- Priesthood of all believers