Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition facts for kids

The Rae–Richardson Arctic expedition of 1848 was an early British journey to find out what happened to the lost Franklin Polar Expedition. Led by Sir John Richardson and John Rae, the team traveled over land. They explored areas near the Mackenzie and Coppermine rivers, which were part of Franklin's planned route. They did not find Franklin's group, and the search for them continued for several more years.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Journey

By 1847, people thought that Franklin's ships were probably stuck in ice. The British Admiralty, which was like the navy's headquarters, planned a three-part rescue mission. They wanted to check the three most likely ways Franklin's crew might have escaped. These were east through Lancaster Sound, south towards the Mackenzie River, or west through the Bering Strait.

Sir John Richardson had been on earlier Arctic trips with Franklin. He was given the job of searching the Mackenzie River area. His plan was to explore the coast between the Mackenzie and Coppermine rivers. He also planned to check the shores of Victoria Island and the Wollaston Peninsula.

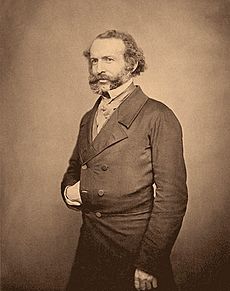

It was thought there was a passage between these lands. This would have been the most direct way to travel, matching Franklin's original orders. John Rae, from the Hudson's Bay Company, joined this effort. Rae had 15 years of experience in the region. He also had great respect for the local Indigenous people. The plan was for the expedition to search further by staying for winter near Great Bear Lake.

Hunting in Rupert's Land, the Hudson's Bay Company area, had been poor recently. So, extra supplies were sent there in 1847 before Richardson left. These supplies included over 17,000 lb (7,700 kg) of canned pemmican, a type of dried meat. Four half-ton boats were built for river travel. Each boat was about 30 by 6 ft (9.1 by 1.8 m). The two smaller boats could fit inside the two larger ones for shipping.

Five sailors and fifteen soldiers, called sappers and miners, were chosen for the crew. Many of them were also good at carpentry, blacksmithing, and engineering. The crew and supplies left England on June 15, 1847. They were heading for Hudson Bay.

Ice in the Hudson Straits delayed the supply and crew landing until September 8. Meanwhile, Richardson finished his preparations in England. The Hudson's Bay Company helped by moving extra supplies along their planned route. Workers were sent to fish and cut firewood for the expedition. Richardson and Rae left Liverpool on March 25, 1848. They landed in New York on April 10, and reached Montreal four days later.

Two canoes, mostly paddled by Iroquois and Chippewa people, took Richardson, Rae, and their gear. They arrived at Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River on June 13. Traveling by canoe and carrying their boats over land, Richardson and Rae met the advance team. This happened at Methy Portage on June 28. They continued down the Slave River with them until mid-July. On the 17th, they reached Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake, where the Mackenzie River begins.

Reaching the Winter Camp

They kept traveling through areas where several native tribes lived. On August 2, they passed the tree line, where trees stop growing. The group sometimes met Inuit people in their kayaks and umiaks. They started trading with them. These Inuit were asked questions but said they had not seen any Europeans or ships. This included during Rae's trip through the area in 1826. They kept going, hunting as they went. They passed Franklin Bay and Cape Parry, where they first saw drifting pack ice. Their journey slowed down for the rest of the month. Wind, winter, and ice often made it hard to move forward.

By the end of August, they found a path through the ice towards the Coppermine River. But the ice stopped them from reaching their autumn goal of Wollaston Land by water. They continued to gather information, trade, and get help from Inuit groups they met. They kept going over land. On September 5, they crossed the Richardson River in small groups using a portable Halkett boat.

As they traveled, they threw away equipment to make their loads lighter. By September 15, they reached the advance team. This team had already started building their winter home, called Fort Confidence. They had also gathered supplies for winter. Here, they spent the winter. They regularly hunted, fished, and traded with the local Inuit to make their food last longer. Throughout the winter, Rae explored the lands between the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. In December, the temperature dropped to −60 °F (−51 °C). By late May, the snow was melting, and seasonal wildlife began to return.

Rae's Summer Journey in 1849

Only one boat was available, so it was decided that Rae would continue the search alone. Rae started setting up supply points and sending out hunters in April using dog sleds. On June 7, Rae left with six men. This included two Cree Indians and an Inuk named Albert One-eye. Their goal was to explore the Coppermine River to the Arctic Ocean. They also wanted to search the coasts of Wollaston and Victoria Lands for Franklin. At first, they moved slowly over the frozen Dease River by sledge. They reached the open waters near Point Mackenzie on July 14.

Here, seven Inuit visited them. They said that the people of Wollaston Land had not seen any Europeans, boats, or ships. On the 16th, they reached Back's Inlet. They spent three days with these Inuit hosts, mapping the area. Bad weather and ice slowed their progress along the coast. They finally made camp until conditions allowed them to travel. They finally pushed off from the coast into ice-filled waters on August 19.

They made some slow progress through the pack ice. But by the 23rd, they decided to give up on reaching Wollaston Land. The return to their base was hard. A portaging accident caused the death of the Inuk, Albert, and they lost their only boat at Bloody Falls. This was the only death during Rae's exploration. They continued back across land. They reached the Coppermine River on the 29th. Two days later, they returned to Fort Confidence.

At the same time, the same bad conditions stopped another expedition from reaching the Coppermine River from the north. The next summer, Rae left messages for the local native people. He asked them to prepare for a possible meeting with the Ross expedition in 1850.

Richardson's Return Journey

Richardson's main group left Fort Confidence on May 7. This was a full month before Rae set out for Wollaston Land. They traveled mostly by boat. The warming weather meant they couldn't use sleds much. They camped on the shores of Great Bear River for a month. They were waiting for a large boat to ship their supplies. By June 8, they learned that the ice would not let the boat reach them. So, the group started walking along the river.

By June 14, they had reached Fort Simpson. They stayed there until the 25th. They continued their journey through August and September. They reached Sault Ste. Marie on September 25. There, a steam vessel took them further to Lake Huron. Richardson returned to Liverpool on November 6, 1849.

Rae Continues the Search

Rae kept exploring and searching for Franklin for several more years. He did this for the Hudson's Bay Company. He set up a base at Fort Confidence on Great Bear Lake starting in 1850.

In 1851, he left Fort Confidence. He went down the Coppermine River and explored the south shore of Victoria Island. During the harsh winters, they shared their limited food with the local Inuit. This made their cooperation stronger. None of the expedition members died. During these trips, Rae kept asking the local native people questions. But no one had any information about Franklin's expedition. No physical evidence was found either.

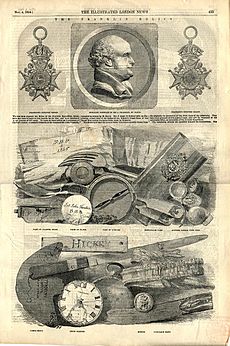

In the spring of 1853, Rae returned to Back's Great Fish River. He went northeast from its mouth to explore more of Boothia. Here, he met Inuit who had objects he recognized as belonging to the Franklin expedition. Rae bought as many of these objects as he could. Talking to others in the area showed that the Inuit had met the last members of Franklin's crews in the spring of 1850.

What Happened to Franklin?

In July 1854, John Rae sent a message from his camp at Repulse Bay to the head of the Admiralty.

"Repulse Bay, July 29.

SIR: – I have the honor to mention, for the information of my Lord's Commissioners of the Admiralty, that during my journey over the ice and snow this spring, with the view of completing the survey of the West shore of Boothia, I met with Esquimaux in the Pelly Bay, from one of whom I learned that a party of "white men" (Kablounans) had perished from want of food some distance to the westward, and not far beyond a large river containing many falls and rapids. Subsequently, further particulars were received, and a number of articles purchased, which place the fate of a portion, if not of all, of the then survivors of Sir John Franklin's long lost party beyond a doubt – a fate terrible as the imagination can conceive.

In the spring, four winters past, (spring, 1850,) a party of "white men," amounting to about forty, were seen travelling southward over the ice, and dragging a boat with them, by some Esquimaux, who were killing seals near the North shore of King William's Land, which is a large island. None of the party could speak the Esquimaux language intelligibly, but by the signs of the natives were made to understand that their ship or ships, had been crushed by the ice, and that they were now going to where they expected to find deer to shoot. From the appearance of the men, all of whom, except one officer, looked thin, they were then supposed to be getting short of provisions, and purchased a small seal from the natives. At a later date the same season, but previous to the breaking up of the ice, the bodies of some thirty persons were discovered on the continent, and five on an island near it, about a long day's journey to the N. W. of a large stream, which can be no other than Back's Great Fish River, (named by the Esquimaux Doot-ko-hi-calik,) as its description, and that of the low shore in the neighborhood of Point Ogle and Montreal Island, agree exactly with that of Sir George Back.

[...]

There appeared to have been an abundant stock of ammunition, as the powder was emptied in a heap on the ground by the natives, out of the kegs or cases containing it; and a quantity of ball and shot was found below high-water mark, having probably been left on the ice close to the beach. There must have been a number of watches, compasses, telescopes, guns (several doubled barrelled,) &c., all of which appear to have been broken up, as I saw pieces of those different articles with the Esquimaux together with some silver spoons and forks. I purchased as many as I could get. A list of the most important of these I enclose, with a rough sketch of the crest and initials of the forks and spoons. These articles themselves shall be handed over to the Secretary of the Hudson's Bay Company on my arrival in London.

None of the Esquimaux with whom I conversed had seen the "whites," nor had they ever been at the place where the bodies were found, but had their information from those who had been there, and who had seen the party when travelling.

I offer no apology for taking the liberty of addressing you, as I do so from a belief that their Lordships would be desirous of being put in possession at as early date as possible of any tidings, however meagre and unexpectedly obtained, regarding this painfully interesting subject.

I may add that, by means of our guns and nets, we obtained an ample supply of provisions last autumn, and my small party passed the winter in snow houses in comparative comfort, the skins of the deer shot affording abundant warm clothing and bedding. My spring journey was a failure, in consequence of an accumulation of obstacles, several of which my former experience in Arctic travelling had not taught me to expect. I have &c.,

JOHN RAE, C.F.,

Commanding Hudson's Bay Company's Arctic Expedition."

Rae later stopped charting the area. Instead, he focused on answering questions from those interested in Franklin's fate. He returned to England on October 22. He found that the Admiralty had given his private message to the newspapers. It was published in the London Times on October 23. This caused a lot of public sadness and anger.

Rae's Lasting Impact

Rae not only found out what happened to Franklin's lost expedition. He also completed a large survey of the west coast of Boothia. He proved that King William's Land was, in fact, an island. His furthest point north was near Cape Porter.

Rae received a £10,000 reward for solving the Franklin mystery. But by then, he was largely forgotten by history. Even though Francis Leopold McClintock later found bones on King William Island that supported Rae's story, Rae was never fully forgiven for bringing the bad news. Rae retired from exploring soon after. His contributions as an explorer were finally recognized when he was chosen as a member of the Royal Society in 1880.

Several places in Canada were named after Rae. These include Rae Strait (between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula), Rae Isthmus, and Rae River in Nunavut. Also, Mount Rae in the Canadian Rockies of Alberta, and Fort Rae and the village of Rae-Edzo (now Behchokǫ̀) in the Northwest Territories.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |