Sam Houston and Native American relations facts for kids

Sam Houston had a special connection with Native Americans, especially the Cherokee people from Tennessee. He was adopted by them and later became a negotiator, planner, and creator of fair laws for Native Americans. He served as a lawmaker, governor, and president of the Republic of Texas.

Around 1808, Houston left his home and was welcomed by John Jolly, a leader of the Cherokee. Houston lived in Jolly's village for three years. He learned Cherokee customs and traditions, which taught him to be honest and fair. He also learned to speak the Cherokee language. Houston felt that Native Americans were often treated unfairly in treaties with the United States government. This belief guided his decisions as a military officer, treaty negotiator, and in his roles as governor of Tennessee and Texas, and as president of the Republic of Texas.

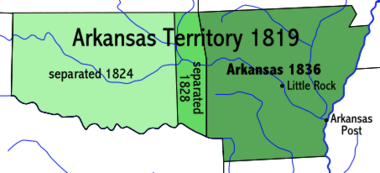

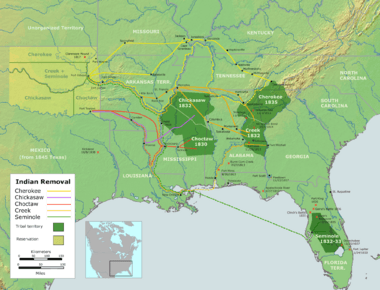

Houston was a close friend and supporter of Andrew Jackson. He fought with the Cherokee against the Creek at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, where he was injured. In 1817 and 1818, he helped arrange treaties that moved Cherokee people southwest to the Arkansas Territory. He worked as a lawyer for about ten years. Then he was elected a congressman from Tennessee, and later governor of the state.

In 1829, Houston resigned as governor of Tennessee. He returned to the Cherokee who had moved to the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). This move was based on a treaty from 1828. He became a legal citizen of the Cherokee Nation and lived like other tribal members. He worked as a representative for the Cherokee, negotiating with the United States government and other Native American tribes. He helped find dishonest Indian agents and pushed for proper land titles for the Cherokee in their new lands.

Houston married Diana Rogers Gentry under Cherokee law in 1830. Houston and Diana ran a trading post called Wigwam Neosho near Fort Gibson, in what is now Oklahoma. In 1832, he accepted a job to negotiate with the Comanche tribe in Texas.

The Alabama–Coushatta Tribe were allies of Houston during the Texas Revolution. In 1836, they gave supplies to Texans fleeing Antonio López de Santa Anna's army during the Runaway Scrape. They also guided Houston's army. Houston negotiated a treaty for the tribe to get land between the Sabine and Neches Rivers.

As the United States expanded westward, Native American tribes were pushed further west. As president of the Republic of Texas, Houston created policies to offer trading chances, safety, and peace for Native Americans. He strongly supported the right of Native Americans to own land. In 1854, as a senator from Texas, Houston helped create the Alabama–Coushatta Indian Reservation.

Houston became governor of Texas when the country was moving towards the American Civil War. He believed Texas should not leave the Union. But Texas did leave, and all state officials except Houston took an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy. Because he refused, he was removed from office. However, he was able to get the Confederate States War Department to release all draftees from the Alabama-Coushatta tribe, who had stayed out of the conflict.

Contents

Growing Up with the Cherokee

Early Life and Cherokee Friends

Sam Houston was born in Virginia. His father died in 1806 when Sam was eleven. Two years later, his mother moved the family to the wilderness of Blount County, Tennessee. They settled near Maryville on a large piece of land. The Houstons built a cabin and opened a store.

Sam did not like farm work or working in the store. He often went into the woods, where he met Cherokee people. He found them peaceful and friendly. The family farm was close to the Cherokee Nation's border. Cherokee members often traded at the Houstons' store. The Cherokee were one of the Five Civilized Tribes.

Houston did not like school much. He preferred reading books from his father's library, especially Greek classics. These books taught him about faraway lands and history.

In 1809, Houston went to live with the Cherokees along the Hiwassee River. His brothers found him at John Jolly's home. Houston told them he preferred living with the Cherokee, which he did for three years. Jolly, also known as Ahuludegi, led the tribe. He taught the importance of fairness and honesty. Houston called Jolly his "Indian Father" and saw the Cherokees as his family. Jolly adopted him and gave him the Cherokee name Colonneh, meaning "the Raven." Houston wore their clothes, spoke their language, danced, and played their games. He hunted with the boys and explored with the girls. These experiences helped shape his character and gave him skills for his military and leadership roles.

Houston visited his family sometimes for clothes or money. He wrote to his cousins, showing care for his younger brother and sisters. He sometimes got into debt from buying gifts for tribal members. So, he took a job in a store in Kingston.

In 1812, Houston returned home and opened a school at age 19. He charged eight dollars per term, payable in cash, cotton, or corn. His school was successful. He later said he felt more pride from this than from any other job. Facing debts again, he joined the United States Army in March 1813. He became a sergeant the same day. Houston fought in the Creek War and led a charge against the Creek. He rose in rank and formed a lifelong friendship with Andrew Jackson. He fought with the Cherokee during the War of 1812 at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Houston was badly hurt by an arrow in his thigh. He was not expected to live but recovered enough to go home. He was promoted to first lieutenant under Jackson in May 1817.

Helping Tribes Move West

As white settlers moved west, there was pressure to move Native Americans from the Southern United States to land west of the Mississippi River. This idea was suggested by Thomas Jefferson in 1803. By 1816, Jackson wanted all Cherokee to move west and thought Houston could help. In 1817, after a treaty with the Cherokee, Jackson appointed Houston to help carry out the treaty. Houston could speak Cherokee and knew many of the people who were to move. He believed the removal of Cherokee from East Tennessee was going to happen. He felt the Cherokee were moving to a place where they could live in peace. The Cherokee knew him as the Great Chief of the whites.

In February 1818, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun strongly criticized Houston. Houston had worn Native American clothing to a meeting with Calhoun and Cherokee leaders. Houston thought it showed respect, but Calhoun felt it was wrong for an army officer. Houston resigned from the army in 1818.

Houston continued to work with the Cherokee. The treaty he negotiated in 1818 said tribal members should get the same amount of land they had in Tennessee. They were to have free use of waterways and receive money for improvements. Unlike the later Trail of Tears, there was no forced removal of the Cherokee. Their move was well-organized, often by river boat. But when they arrived, they found their new land was hunting grounds for the Osage and Quapaw tribes.

Returning to the Cherokee

Arrival

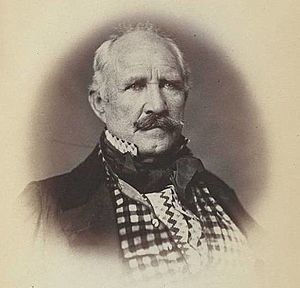

After becoming a lawyer in 1819, Houston was elected a congressman in 1823. In October 1827, he became governor of Tennessee. In January 1829, Houston married Eliza Allen. Their marriage quickly ended, and in April 1829, Houston resigned as governor. Soon after, he traveled west to rejoin the Cherokee. He reunited with Jolly's tribe in mid-1829.

After a difficult journey, Houston arrived by steamboat. Chief Jolly had been told Houston was coming and met him. The old chief hugged him warmly. He said, "My son, many years have passed since we met. I heard you were a great chief among your people. Now you have returned to our wigwam. I am glad. The Great Spirit sent you to help us. We are in trouble, and you can give us advice. My home is yours, my people are yours. Rest with us."

Houston sought peace from white society. He went to Jolly's lodge to live among the people who gave him the happiest time of his life. In a letter to Jackson, he described himself as being in "the darkest, direst hour of human misery" after his marriage failed.

Life Among the Cherokee

Jolly had a large farm with many enslaved people and cattle. He was a kind host. Wealthy Cherokee lived like southern planters. They bought fine goods and built nice homes. But they still enjoyed their own cultural traditions. For example, Houston and Jolly shared food from a common spoon, an old tradition among friends.

On October 31, 1829, Houston became a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. This gave him all the rights and duties of a native member. A committee approved him after looking at his past contributions and future plans. Being a Cherokee citizen made him a more important representative for the tribe. He was also a Council leader. He was uniquely able to help them because he knew how the U.S. government worked, spoke Cherokee, and understood their needs.

Wanting to fully fit in, he avoided white people. He wore native clothing and turbans, grew a goatee, and braided his hair. He reportedly would not speak English and used an interpreter for white men. He carried only a bow and arrow, which he learned to use as a boy. In 1829, Houston took part in a seven-day Green Corn Ceremony. This celebration involved cleansing past wrongs, dancing, and games. He also joined tribal government and religious events. Houston lived by Cherokee customs and traditions. He understood their view of the world better. He shared their love for the land and forests. He saw how white men had deceived them, brought diseases, and changed their way of life. Houston worked to protect them and act in their best interests.

Houston was often sad into 1831. He tried to get a seat on the Cherokee tribal council but lost. After his mother died in September 1831, he decided to stop drinking and change his life.

Marriage to Diana Rogers Gentry

Houston married Diana Rogers Gentry under Cherokee law in the summer of 1830. Diana was the daughter of Chief John "Hellfire" Rogers, a Scots-Irish trader, and Jennie Due, Jolly's sister. John Rogers was a captain in the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. He fought under Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, alongside his sons and Houston.

Diana was a tall, beautiful woman with Scottish and English background and some Cherokee heritage. She may have been known as Tiana among the Cherokee. She had been married before to David Gentry. David died in a battle with the Osage people.

Houston called Diana "Hina." They lived near Fort Gibson on the Neosho River and ran a trading post from 1829 to 1833. Diana stayed in Indian Territory when Houston went to Texas in 1832. Their marriage ended peacefully, and she later remarried. Diana died in 1838.

Protecting Native American Rights in Texas

Because of Houston's government experience and his connection with President Jackson, many local Native American tribes asked him to help settle disputes. This allowed them to speak directly to the Jackson administration. In December 1829, Houston, as an ambassador for Chief Jolly, went to Washington, D.C. He met with Jackson, who then removed dishonest Indian agents. Jackson also ordered surveys of Cherokee lands so they could get proper titles.

Houston accepted a mission from Jackson to negotiate with the Comanche. He wanted to stop them from attacking other Native Americans moving westward. He crossed into Texas on December 2, 1832, and met with the Comanche in San Antonio. They agreed to meet with government officials in May 1833.

First Term as President of Texas (1836–1838)

One of the first jobs for the new Republic of Texas was to create a policy for Native American tribes. Houston, who became president in 1836, planned to protect the frontier, create trade, and promote peace. On December 5, 1836, a law was passed giving Houston the power to protect Native Americans by setting up trading posts. Houston had sympathy for native peoples. He provided riflemen and militia to protect the frontier. The law allowed for treaties, agents, and giving goods to Native American tribes.

Relations between white settlers and native peoples became harder as Native Americans were pushed west and their land was taken. Houston strongly believed in Native Americans' rights. He worked hard for the Republic to find common ground with different tribes. He insisted on their right to own land. Many tribes came to respect him as a friend. Sometimes, hundreds of Native Americans would camp, eat, and celebrate at his farm. In 1836–1837, Houston used the peaceful Texas Delaware tribe to guard the Texas border.

In 1838, Houston often disagreed with the United States Congress. He had to stop the Córdova Rebellion, a plan to help Mexico reclaim Texas with help from the Kickapoo Indians. By keeping troops out of Native American lands, Houston avoided some serious conflicts. By the end of his first term in December 1838, the native peoples of Texas were worried about white settlers moving onto their lands.

Houston could not run for re-election right away. Mirabeau B. Lamar became president in 1838. Lamar wanted to remove or even destroy hostile tribes. He wanted friendlier tribes moved to reservations. Lamar's policies led to the Texas–Indian wars. The Cherokee were forced out of Texas in 1839.

Houston's policy of friendship and peace, even with tribes that raided white settlements, had better results for Native Americans. It also cost fewer lives and less money for the Republic. Houston's defense of his Native American friends was often discussed in newspapers and debated in the Texas Congress. Houston was elected president again in 1841.

Second Term as President of Texas (1841–1844)

When Houston left the presidency the first time, many Texans supported Lamar's strong anti-Indian policies. But after the Great Raid of 1840 and many smaller raids, Texans wanted to end the fighting. They favored more peaceful talks, which led to Houston's re-election.

Houston's Native American policy was to reduce the army and create four new companies of rangers to patrol the frontier. Houston ordered the Texas Rangers to protect Native American lands from settlers and illegal traders. He wanted to end the cycle of anger and revenge that had grown under Lamar. Under Houston's policies, the Texas Rangers could punish wrongs by native peoples, but they were never to start conflicts. Troops were told to find and punish the actual wrongdoers, not to attack innocent people just because they were Native Americans.

Houston began to negotiate with the Native tribes. The Caddo were the first to agree in August 1842. Houston then expanded this to include all tribes except the Comanche, who still wanted war. In March 1843, Houston reached an agreement with the Delaware, Wichitas, and other tribes. At this point, Buffalo Hump, a Comanche war chief who trusted Houston, began to talk. In August 1843, a temporary agreement led to a ceasefire between the Comanches and Texans. On September 29, 1843, his government negotiated the Treaty of Bird's Fort with many tribes. In October 1843, the Comanche agreed to meet Houston to negotiate a similar treaty. In early 1844, Buffalo Hump and Old Owl made the Treaty of Tehuacana Creek. They agreed to return all white captives and stop raiding Texan settlements. In return, military action against them would stop, more trading posts would be built, and their chosen boundaries for the Comancheria would be recognized.

Comanche allies, including the Waco, Tawakoni, Kiowa, and Wichita, also agreed to join the treaty. However, the Texas Senate changed the treaty. They removed the boundary that would have kept white settlers out of the Comanche lands. This caused Buffalo Hump to reject the changed treaty, and fighting started again.

A Voice for Native Americans in the U.S. Senate (1846–1859)

In February 1846, the Texas legislature chose Houston as one of the first two U.S. senators from the state. Houston joined the Democratic Party. He was reelected to the Senate in January 1853. He remained a strong supporter of Native American rights for thirteen years, even though it was not popular and upset many Texans.

Houston was the only southern Democrat in the U.S. Senate who voted against the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854. This bill would have allowed new territories to decide on slavery themselves. During debates, Houston asked what would happen to the forty thousand Native Americans living in the area. He spoke for them, saying there was "little hope that any appeal I can make for the Indians will do any good." He often spoke in the Senate to ask for justice for "a race of people whom I am not ashamed to say have called me brother."

Also in 1854, Houston helped Texas set aside 1,280 acres for the Alabama-Coushatta Indian Reservation. This reservation has since grown to 4,500 acres. In January 1855, Senator Houston gave a speech in the U.S. Senate defending the Comanche and other Texas tribes. He remembered a time of peace in Texas from 1835 to 1838. He said the Comanches would visit peacefully and return home happy, unless they were treated badly. He noted that this peace cost the government very little money each year.

He explained that a new government came in and wanted to "exterminate the Indians." They attacked a friendly tribe living near settlements. Houston said they wanted to "kill off 'Houston's pet Indians'."

In early 1855, conflict grew along the Texas border. Native American war parties from north of the Red River raided white settlements. These attacks caused a political uproar. White settlers demanded that Texas fight the raiders. Houston lost his Senate seat because he opposed harsh actions against Native Americans.

Houston's Final Years

During Houston's last term as Governor of Texas, the Texas Secession Convention voted for Texas to leave the Union on February 1, 1861. Texas became part of the Confederate States of America on March 1. Houston, like all other officials, was expected to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy. He refused and was removed from office on March 16. In his final years, Houston's friends from the Alabama-Coushatta tribe visited him. Houston managed to get the Confederate War Department to release all draftees from the Alabama-Coushatta tribe, who had stayed out of the conflict.

Legacy

The Cherokee Removal Memorial Park, overlooking Hiwassee Island, honors the relationship between Sam Houston and Native Americans who lived in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. It is near Dayton, Tennessee.

Samuel Houston Mayes, named after his parents' friend, was the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory from 1895 to 1899.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |