Taíno facts for kids

The Taínos were an indigenous people who lived in the Caribbean islands long before Christopher Columbus arrived. They originally came from the coast of South America. Around the year 1200 CE, they started moving north. They settled in the island chains known as the Lesser Antilles and the Greater Antilles.

When Christopher Columbus first reached the Americas, the Taínos were living in places like the Bahamas, Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (which is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and Puerto Rico. They were also on some islands in the northern Lesser Antilles. The Taínos had a unique culture, different from other groups like the Arawak people. They were the very first people the Spanish explorers met in the Americas.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Taíno" was given by Columbus. When he met some of the native men, they said "Taíno, Taíno." This meant "We are good, noble." Columbus thought this was the name of their people.

Experts often divide the Taínos into three main groups. The Classic Taíno lived on Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. The Western Taíno (sometimes called sub-Taíno) were found in Jamaica, Cuba (most of it), and the Bahamas. The Eastern Taíno lived from the Virgin Islands to Montserrat.

The Taínos living in the Bahamas were known as the "Lucayan." At that time, the Bahamas were called the Lucayas. The Lucayan Taínos had a simpler culture compared to other Taíno groups.

Where Did They Come From?

Most experts believe the Taínos' ancestors traveled from the central Amazon Basin area. From there, they moved to the Orinoco Valley. Then, they journeyed through Guyana and Venezuela to reach the Caribbean islands.

Another idea suggests that their ancestors might have come from the Colombian Andes mountains. The Taíno culture as we know it developed mainly on the larger islands of the Greater Antilles.

Daily Life and Culture

Taíno society had two main classes. There were the naborias, who were the common people. Then there were the nitaínos, who were the nobles. Both classes were led by chiefs called caciques. A cacique could be a man or a woman. There were also bohiques, who were like medicine men or spiritual leaders.

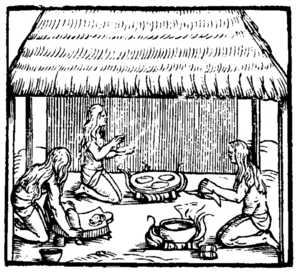

The Taínos lived in villages called yucayeques. The villages in the Bahamas were usually the smallest. They built large, round houses called bohio. Many families lived together in one bohio. The cacique and their family lived in a rectangular house called a caney. People slept in cotton hammocks, which they called hamacas.

The Taínos loved to play a ball game called batey. The playing field was also called batey, and it was a place for dances and other gatherings. The cacique would sit on a special wooden chair called a duho or dujo during these events.

Social Structure

The caciques inherited their leadership position through their mother's noble family line. This means social status was passed down through the female side of the family. The nitaínos often served as sub-chiefs in villages, helping to organize the work of the naborias. The bohiques were respected for their healing abilities and their power to communicate with the gods. People would ask them for permission before starting important tasks.

Caciques had special privileges. They wore golden pendants called guanín. They lived in square bohíos instead of the round ones used by common villagers. They also sat on wooden stools to be higher than their guests.

Taíno women were very skilled at farming, which was a main source of food. The men also fished and hunted. They made fishing nets and ropes from cotton and palm trees. Their dugout canoes, called kanoa, came in different sizes. Some were small for two people, while others could hold up to 150! For hunting, they used bows and arrows, sometimes adding poisons to their arrowheads.

Taíno women often wore their hair with bangs in front and longer in the back. They sometimes wore gold jewelry, paint, or shells. Taíno men and unmarried women usually didn't wear clothes. After marriage, women wore a small cotton apron called a nagua.

The villages, or yucayeques, had a central plaza. This plaza was used for games, festivals, religious ceremonies, and public events. Here, they performed areitos, which were ceremonies celebrating the achievements of their ancestors.

The Taíno played a ceremonial ball game called batey. Teams had 10 to 30 players and used a solid rubber ball. Usually, men played, but sometimes women joined too. The Classic Taíno played in the village's main plaza or on special rectangular courts called batey. These games might have been used to settle disagreements between communities. Chiefs often made bets on the game's outcome.

The Taínos spoke an Arawakan language. They also used an early form of writing with petroglyphs, which are designs carved into rocks. You can still find these at Taíno archeological sites in the West Indies.

Many words we use today came from the Taíno language. These include barbacoa ("barbecue"), hamaca ("hammock"), kanoa ("canoe"), tabaco ("tobacco"), sabana (savanna), and juracán ("hurricane").

For fighting, the men made wooden war clubs called macanas. They also decorated their faces with war paint to look fierce to their enemies.

Food and Farming

Taíno meals included vegetables, fruit, meat, and fish. Even though there weren't large animals in the Caribbean, they hunted and ate small ones. These included hutia (a type of rodent), lizards, turtles, and birds. They used spears to catch manatees and caught fish with nets, spears, traps, or hooks. They even used trained birds to decoy wild parrots. The Taínos kept live animals like fish, turtles, hutias, and dogs in special pens until they were ready to eat them.

The Taíno people were very skilled fishermen. One clever method involved hooking a remora (a suckerfish) to a line from their canoe. They would wait for the remora to attach itself to a larger fish or a sea turtle. Once it did, someone would dive in to get the catch. Another method involved crushing poisonous senna plants and throwing them into streams. The fish would get stunned and be easy to collect. This didn't make the fish unsafe to eat. The Taínos also gathered mussels and oysters from mangrove roots in shallow waters.

Taíno groups on islands like Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, and Jamaica relied more on farming. They prepared fields for important root crops like yuca (also known as cassava) by making mounds of soil called conucos. This helped the soil drain better, made it more fertile, and prevented erosion. It also allowed them to store crops in the ground for longer. Less important crops like corn were grown in clearings made by cutting and burning plants (the slash-and-burn method).

The main root crop was yuca or cassava. It's a woody plant grown for its edible, starchy root. They planted it using a coa, a kind of hoe made entirely of wood. Women processed the poisonous type of cassava by squeezing out its toxic juices. Then, they ground the roots into flour to make bread. Batata (sweet potato) was another important root crop.

Tobacco was grown by people in the Americas for centuries before Columbus arrived. Columbus wrote in his journal about how the native people smoked dried herbs wrapped in a leaf. Tobacco, a word that comes from Taíno, was used in medicine and religious ceremonies. The Taíno people smoked dried tobacco leaves using pipes and cigars. They also crushed the leaves finely and inhaled them through a hollow tube. Their farming tools were simple but effective. Their main tool was a planting stick called a "coa," about five feet long with a sharp point hardened by fire.

Unlike people on the mainland, the Taínos didn't grind corn into flour for bread. They cooked and ate it right off the cob. Corn bread would get moldy too quickly in the Caribbean's humid climate. Corn was also used to make an alcoholic drink called chicha. The Taínos also grew squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, and pineapples. Around their houses, they grew tobacco, calabashes (bottle gourds), and cotton. They also gathered fruits and vegetables from the wild, such as palm nuts, guavas, and Zamia roots.

Taíno People Today

Even though the word Taíno was originally a name given to them by outsiders, many people today who are descendants of the Taínos are now proudly using the name. They are showing their Taíno Caribbean-Indigenous identity. You can find rural communities that have kept Taíno customs and identities on Caribbean islands like Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico.

Modern Taíno Communities

Cuba

In some isolated parts of eastern Cuba, like Yateras and Baracoa, communities with strong Taíno ancestry still exist today. They continue to practice cultural traditions that came from the Taíno people.

Dominican Republic

A historian named Frank Moya Pons found that Spanish colonists often married Taíno women. Over time, some of their mixed-race children married Africans, creating a new mixed culture. Records from 1514 show that 40% of Spanish men on Hispaniola had Taíno wives. However, Spanish documents in the 16th century mistakenly said the Taíno were extinct.

Despite this, experts note that people in the rural Dominican Republic still have parts of Taíno culture. This includes how they speak, their farming methods, food, medicine, fishing, technology, architecture, oral history, and religious beliefs. Even though these traditions might be seen as old-fashioned in cities, some families and individuals in these rural communities identify as Taíno.

Jamaica

There is evidence that some Taíno women and African men married and lived in isolated Maroon communities in the mountains. These communities were quite independent from Spanish rule. For example, when Jamaica was a Spanish colony, both Taíno men and women escaped to the Bastidas Mountains (now the Blue Mountains). There, the Taíno mixed with escaped enslaved Africans. They were among the ancestors of the Jamaican Maroons in the east. Today, the Maroons of Moore Town say they are descended from the Taíno.

United States

In the 2010 U.S. census, many people in Puerto Rico identified as Native American. Specifically, 1,098 people said they were "Puerto Rican Indian," 1,410 said "Spanish American Indian," and 9,399 identified as "Taíno." In total, 35,856 Puerto Ricans identified as Native American.

The Guainía Taíno Tribe has been recognized as a tribe by the governor of the US Virgin Islands.

Taíno DNA Today

In 2018, a DNA study looked at the genome from a tooth of a woman who lived in the Bahamas between the 8th and 10th centuries. The study found that modern Puerto Ricans are more closely related to this ancient Taíno woman than to any other indigenous group in the Americas. Researchers compared her genome to 104 Puerto Ricans who had 10 to 15 percent Indigenous American ancestry. This ancestry was "closely related to the ancient Bahamian genome."

DNA evidence shows that a large part of the people living in the Greater Antilles today have Taíno ancestry. For example, 61% of Puerto Ricans, up to 30% of Dominicans, and 33% of Cubans have mitochondrial DNA that comes from Taíno origins.

Images for kids

-

Taíno zemí sculptureWalters Art Museum

-

Cohoba Spoon, 1200–1500Brooklyn Museum

See also

In Spanish: Taíno para niños

In Spanish: Taíno para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |