Madonna (art) facts for kids

In art, a Madonna is a picture or statue of Mary, either by herself or with her son, Jesus. These artworks are very important icons for both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian churches. The word "Madonna" comes from Italian and means "my lady."

The most common type of Madonna art is called the Madonna and Child. This shows Mary with baby Jesus. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, there are many different styles of these images. They are often named after where a famous artwork is located, like the Theotokos of Vladimir. Sometimes, they are named for how Mary and Jesus are shown, like Hodegetria (meaning "she who shows the way") or Eleusa (meaning "tenderness").

The word "Madonna" started being used in English in the 1600s. It mostly referred to art from the Italian Renaissance. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, these images are usually called Theotokos, which means "God-bearer." A Madonna image usually focuses on Mary as the main figure. She might be surrounded by angels or saints. Other types of art that show stories from Mary's life, like the Annunciation to Mary (when the angel Gabriel told her she would have Jesus), are not usually called "Madonnas."

The very first pictures of Mary appeared in early Christian art around the 2nd or 3rd centuries. These were found in the Catacombs of Rome. They usually showed Mary as part of a story. The classic "Madonna" or "Theotokos" images began to appear around the 5th century. This was after the Council of Ephesus in 431, which officially recognized Mary as the "Mother of God" or Theotokos. This made devotion to Mary much more important. The Theotokos style of art became very significant in the Middle Ages, from the 12th to 14th centuries, in both Eastern and Western Christianity.

An old story says that the first images of Mary were drawn by Luke the Evangelist. Some icons, like the Panagia Portaitissa, are believed to be copies of this original drawing. In Western art, famous artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael created many different kinds of Madonna paintings. Eastern Orthodox art tends to stick more closely to the older, traditional styles.

Contents

What Does "Madonna" Mean?

The word "Madonna" comes from the Italian words Ma Donna, meaning "My Lady." This is similar to the French "Nostre Dame" or "Our Lady." These names show how important Mary became in the Middle Ages. They also show how art was used to honor her.

During the 13th century, Mary was often shown as the Queen of Heaven. She was sometimes seated on a throne, like in the Ognissanti Madonna painting. The idea of the Madonna also reminded people about the importance of purity. Mary's clothing often showed this. The color blue, especially Ultramarine (a very expensive blue pigment), was used for her robes. This color symbolized purity, virginity, and royalty.

While "Madonna" was used in Italy for Mary, it became an art history term in English in the 1640s. It specifically referred to art of Mary from the Italian Renaissance. So, "a Madonna" or "a Madonna with Child" usually means an Italian artwork. You might also hear Mary called "Virgin" or "Our Lady." However, "Madonna" is not usually used for Eastern Orthodox artworks. For example, the Theotokos of Vladimir is often called "Our Lady of Vladimir," but less often the "Madonna of Vladimir."

Different Ways to Show the Madonna

Artists have shown the Madonna in many different ways. Here are some common types:

- Mary Alone: Some Madonna images show Mary by herself, standing. She often looks glorious and is shown praying or giving a blessing. You can see this type in old mosaics in church ceilings.

- Standing Madonna with Jesus: More often, standing images of Mary include baby Jesus. He might look at the viewer or raise his hand to give a blessing. The famous Byzantine image, the Hodegetria, was originally this type. This style is common in sculptures made from ivory, stone, or wood. Raphael's Sistine Madonna is a famous painting of this type.

- Madonna Enthroned: This style shows Mary and Jesus seated on a throne. It started in the Byzantine period and was popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. These images were often large altarpieces (artworks behind an altar). In older examples, angels or saints might surround the throne. In Renaissance art, saints might be grouped more casually, a style called a Sacra conversazione.

- Madonna of Humility: In these images, Mary is sitting on the ground or on a low cushion. She often holds Jesus on her lap. This style became popular because of the Franciscan religious group. It spread quickly through Italy and other parts of Europe.

- Half-Length Madonnas: These show Mary and Jesus from the waist up. This is a very common style for painted icons in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Each painting often shows a specific quality of the "Mother of God." Half-length paintings are also common in Italian Renaissance painting, especially in Venice.

- Seated Madonna and Child: This style became popular in 15th-century Florence. These artworks are usually small, made for a small altar or for use at home. They show Mary holding Jesus in a relaxed, motherly way. These paintings often include symbols that hint at the future suffering of Jesus.

- Adoring Madonna: Popular during the Renaissance, these images show Mary kneeling and adoring the Christ Child. They were usually small and meant for personal prayer. Many were made from glazed clay or paint. Examples include Madonna Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child.

- Nursing Madonna: Also called Virgo Lactans or Madonna Lactans, this shows Mary breastfeeding baby Jesus. Leonardo da Vinci's Madonna Litta is an example.

- Woman of the Apocalypse: This style shows Mary based on descriptions from the Bible's Book of Revelation.

- Hodegetria: This type of icon shows Mary holding Jesus and pointing to him. She is "showing the way" to salvation. In Western churches, it's sometimes called Our Lady of the Way.

- Eleusa Icon: Also known as the "Virgin of Tenderness," this icon shows Jesus nestled close against Mary's cheek.

- Rest on the Flight into Egypt: This artwork shows Mary, Joseph, and baby Jesus resting during their escape to Egypt. They are usually shown in a natural setting.

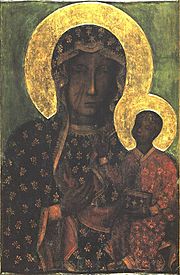

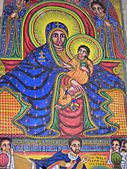

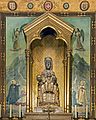

- Black Madonna: These are statues or paintings of Mary and Jesus where both figures are shown with dark skin. They are found in both Catholic and Orthodox countries.

- Mary in Islam: Mary (Maryam) is a very respected figure in Islam. She is sometimes shown in Islamic art, even though Islam usually avoids pictures of people.

- Girlhood of Mary: This shows Mary as a child, often learning to sew. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's The Girlhood of Mary Virgin is a famous example.

- Annunciation: This art shows the angel Gabriel telling Mary that she will have a son, Jesus, through a virgin birth.

- Death, Assumption, and Coronation of the Virgin: These artworks show Mary's death, her being taken up to Heaven, and her being crowned Queen of Heaven by Jesus. They often include birds, symbolizing the Holy Spirit.

- Holy Family: This shows Mary, Joseph, and Jesus together. Sometimes other saints are included.

- Marian Apparition: This shows Mary appearing to people. The icon of Our Lady of Guadalupe is very famous and shows Mary with a sunburst behind her.

History of Madonna Art

One of the earliest images of the Madonna and Child is a painting on a wall in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome. It shows Mary sitting and feeding Jesus, who looks out at the viewer.

The first clear images of Mary and Jesus were developed in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium). Even though some people there didn't like pictures in churches, images of Mary became very important. When Pope Agapetus I visited Constantinople in 536, he was accused of not respecting images of Mary. Early Eastern examples show Mary on a throne, wearing a crown, with Jesus on her lap.

In Western Europe, artists first copied these Byzantine styles. But as devotion to Mary grew in the 12th and 13th centuries, many new styles appeared. In Gothic and Renaissance art, Mary often sits with Jesus on her lap or in her arms. In older pictures, Mary is on a throne, and Jesus might be raising his hand to give a blessing. Later, in 15th-century Italy, baby John the Baptist might also be in the picture.

Late Gothic sculptures sometimes show Mary standing with Jesus in her arms. Some images, like Mary feeding Jesus (the Madonna Litta), were mostly for private prayer at home.

Early Images

After the First Council of Ephesus in 431, devotion to Mary greatly increased. This council confirmed her title as Theotokos ("God-bearer"). In mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome from 432–440, Mary doesn't yet have a halo. She also wasn't shown in Nativity (birth of Jesus) scenes at this time, though she was in pictures of the Adoration of the Magi.

By the next century, the image of Mary enthroned with Jesus was common. An example is from Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt. This style, with small changes, has remained popular for showing Mary. The image at Mount Sinai shows Mary's humility and her importance. It also has the Hand of God above, which angels look up to. An early icon of Mary as queen is in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, from 705–707. It shows Pope John VII kneeling, and Jesus reaching out to him.

During this time, the way the Nativity was shown in art became set, especially in the Eastern Orthodoxy. Western art also followed these ideas until the High Middle Ages. Other stories from Mary's life were also developed, often using stories not found in the Bible. The Western Roman Empire was struggling, so the Western Church relied a lot on Byzantine art ideas.

The earliest surviving image of the Madonna and Child in a Western illuminated manuscript is from the Book of Kells (around 800 AD). While beautifully decorated, the figures are simpler compared to Byzantine art of that time. Images of Mary didn't appear in many manuscripts until the 13th century, when book of hours became popular.

The Madonna of humility by Domenico di Bartolo, painted in 1433, is seen as a very new and important religious image from the early Renaissance.

Byzantine Art's Influence on the West

Very few early images of Mary have survived. However, the way the Madonna is shown has roots in old art traditions across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Byzantine icons were very important to Italian art. These icons, made in Constantinople (now Istanbul), were famous for their miraculous powers. Byzantium saw itself as the true Roman Empire. Italians lived there, took part in Crusades, and sometimes even took treasures from Byzantine churches. Later in the Middle Ages, artists from the Cretan school were a main source of icons for the West. They could change their style to fit Western art if needed.

Byzantine art had a long and important role in Western Europe. This was especially true when Byzantine lands included parts of Eastern Europe, Greece, and much of Italy. Byzantine manuscripts, ivory carvings, gold, silver, and fancy fabrics were sent all over the West. In Byzantium, Mary was usually called the Theotokos or Mother of God. People believed that salvation came when God became human. This idea is shown in art by Mary holding her baby son.

The earliest independent images of Mary are found in Rome, the center of Christianity in the medieval West. One is a treasured item in Santa Maria in Trastevere, a Roman church dedicated to Mary. Another, though damaged and repainted, is honored at the Pantheon. Both of these artworks show Byzantine traditions in how they were made. They were originally painted with tempera (egg yolk and ground colors) on wooden panels. This connects them to the ancient Roman history of Byzantine icons. Also, they share the same iconography, or subject matter. Each image highlights Mary's role as a mother, showing her with her infant son. These early images seem to be mostly from the 7th and 8th centuries.

Later Medieval Art

It wasn't until the 12th and 13th centuries that large panel paintings of the Madonna became popular outside of Rome, especially in Tuscany, Italy. Religious groups like the Franciscan and Dominican Orders were among the first to order these paintings. Soon, they became popular in churches, monasteries, and homes. Some Madonna images were paid for by groups called confraternities. These groups met to sing praises to Mary in chapels. Paying for such art was seen as a way of showing devotion.

The cost of these artworks was clear from the use of thin sheets of real gold leaf on parts of the painting not covered by paint. This made the image glow in the light of oil lamps and candles. Even more precious was the bright blue cloak, colored with lapis lazuli, a stone brought from Afghanistan.

A famous example is the Rucellia Madonna (around 1285) by Duccio. This large painting was a visual focus for the Laudesi confraternity in Florence as they sang praises. Duccio made an even bigger Madonna image for the main altar of Siena Cathedral, his hometown. This work, called the Maesta (1308–1311), shows Mary and Jesus at the center of a crowded court. A smaller, more personal image by Duccio, showing Mary holding her son closely, is in the National Gallery in London. This was clearly made for a wealthy Christian's private prayers.

The owner of such a private artwork didn't need to go to church to pray. They could simply open the shutters of their small altar at home. Duccio and other artists of his time used older art styles. This helped connect their new works to the authority of tradition.

Even with new ideas from painters in the 13th and 14th centuries, Mary can usually be recognized by her clothes. When she is shown as a young mother with her newborn child, she typically wears a deep blue cloak over a red dress. This cloak usually covers her head, sometimes with a thin veil. She holds Jesus, who shares her halo and royal look. Often, Mary looks out at the viewer. She acts as a go-between, taking prayers from Christians to her son. However, late medieval Italian artists also followed Byzantine icon painting styles. They developed their own ways of showing the Madonna. Sometimes, Mary's close bond with her child is shown as a tender, sad moment where she only has eyes for him.

Besides paintings, Mary's image also appears in mosaics and fresco paintings on church walls. She is often found high up in the apse (the curved part at the east end of a church). She is also shown in sculptures, from small ivory carvings for private prayer to large stone carvings and free-standing statues. Her image inspired one of the most important fresco series in Italian painting: Giotto's story cycle in the Arena Chapel in Padua, from the early 14th century.

Italian artists from the 15th century onwards built on the traditions set in the 13th and 14th centuries for showing the Madonna.

-

Rest on The Flight into Egypt, around 1510, by Gerard David. It shows a close, tender moment where Mary only has eyes for her Child.

-

Lorenzo Monaco, Florence, around 1410.

The Renaissance Period

The 15th and 16th centuries were a time when Italian painters started to create art about historical events, individual people, and myths. However, Christianity remained very important to their work. Most artworks from this time were religious. While artists painted scenes from the Old Testament and images of saints, the Madonna remained a very popular subject in Renaissance art.

Some of the most famous Italian painters of the 16th century who painted the Madonna were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, Giovanni Bellini, and Titian. They built on the ideas of 15th-century artists like Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Mantegna, and Piero della Francesca. The Madonna was also very popular in Early Netherlandish painting and other parts of Northern Europe.

The most powerful theme for all these artists remained the bond between a mother and child. Even though other subjects, like the Annunciation and later the Immaculate Conception, led to more paintings of Mary alone, the mother-child image was central. The Pietà, which shows Mary holding the dead body of Jesus, became an important subject. It was no longer just part of a story series. This type of art grew from popular statues in Northern Europe. Traditionally, Mary is shown feeling compassion, sadness, and love in these emotional artworks. Even Michelangelo's famous early Pietà shows deep emotion. The tenderness a mother feels for her child is captured, reminding viewers of the moment Mary first held baby Jesus. The viewer is meant to feel sympathy and share in the mother's sadness as she holds her crucified son.

-

The Madonna on a Crescent Moon in Hortus Conclusus by an anonymous painter.

-

Leonardo da Vinci, a study of the Head of Madonna, around 1484.

Modern Madonna Images

In some European countries, like Germany, Italy, and Poland, you can find sculptures of the Madonna on the outside of houses and buildings, or along roads in small shrines.

In Germany, a statue placed on the outside of a building is called a Hausmadonna. Some are very old, from the Middle Ages, while others are still being made today. They are often found on the second floor or higher, sometimes on a corner of a house. Many cities used to have hundreds of them. For example, Mainz had over 200 before World War II. These statues show many different styles. Some Madonnas hold grapes, others are "immaculate" (pure white without child or accessories), and some have roses, symbolizing her life.

In Italy, the roadside Madonna is a common sight. These statues are meant to bring comfort to people who pass by. Some Madonna statues are placed in Italian towns and villages for protection or to remember a reported miracle.

In the 1920s, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed statues called the Madonna of the Trail across the United States. These statues marked the paths of old roads like the old National Road and the Santa Fe Trail.

The painter Ray Martìn Abeyta created works inspired by old Madonna paintings from the Cusco School. He mixed traditional and modern Latino themes, showing the meeting of European and Mesoamerican cultures.

In 2015, artist Mark Dukes created the icon Our Lady of Ferguson. This Madonna and child image is related to the Shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

Mary in Islam

An important event involving Islam and the image of the Madonna happened during the Prophet Muhammad's conquest of Mecca. In 629 CE, Muhammad and a Muslim army conquered Mecca. His first action was to "cleanse" the Kaaba, a holy building, by removing all pagan images and idols from inside.

However, according to historical reports, Muhammad protected a painting of Mary and Jesus, and a fresco of Abraham. He put his hand over them to keep them from being erased. Historian Barnaby Rogerson wrote that Muhammad "raised his hand to protect an icon of the Virgin and Child and a painting of Abraham."

The Islamic scholar Martin Lings described the event in his book about the Prophet. He said that Christians sometimes visited the Kaaba to honor Abraham. One Christian had been allowed to paint an icon of the Virgin Mary and the child Christ on an inside wall of the Kaaba. This painting was very different from the other pagan images. Muhammad placed his hand over the icon of Mary and Jesus, and a painting of Abraham. He told his companion to erase all the other pagan paintings.

Madonna Art in India

In the art history of India, there are interesting similarities between images of the Madonna and Christ Child, and images of Yashoda or Devaki with Krishna. Both the Hindu and Christian figures of the "eternal child" are shown lovingly held on their mother's laps.

There is a temple in Goa, the Shree Devakikrishna Temple at Marcel. When the Portuguese saw the idol of Krishna-Devaki there, they did not destroy the temple. It reminded them of the Virgin Mary and Jesus.

The temple has an impressive idol of Devaki carrying baby Krishna on her hip. This image is unusual because while there are many temples dedicated to Krishna, there are almost no images of Devaki. Historian Anant Dhume compares this idol to the image of Madonna and the Christ child because of their similarities.

During the Portuguese rule in Goa, starting in the 16th century, Indo-Portuguese ivory statues were made that showed these similarities. The Portuguese wanted to control the spice trade and spread their Christian faith. These small, portable ivory statues were used to decorate church altars and Goan homes. They were also sent abroad. Indian artists carved these figures under the guidance of the Jesuits. Art historian Gauvin Alexander Bailey notes that the Jesuit art projects were a partnership. Artists were encouraged to use their own ideas for sacred art. The Jesuits provided small paintings, prints, and sculptures from Europe for Indian sculptors to use as examples. The local artists used their own traditions to create these figures.

One great example of this mix of cultures is the figure called the Good Shepherd Rockery. This artwork shows how different cultures came together in its style and features. It shows how Goan sculptors created images of the divine that were Catholic, European, and South Asian. The child Jesus in this figure, with a round face and smooth skin, might have been inspired by sculptures of baby Krishna.

In Bengal, art studios like Chore Bagan Art Studio produced local prints in the late 1800s. These artists were influenced by European prints of Christ that were available at the time. They might have seen a close connection between the child Christ and Krishna. Jyotindra Jain says that the Chore Bagan Art Studio published a popular picture called "Birth Of Krishna." It was almost entirely based on popular prints of "The Birth Of Jesus Christ." It even copied the presence of the three wise men.

Artists like Jamini Roy also used this image. Jesus and Mary appeared in the paintings of Tyeb Mehta, Krishnen Khanna, Madhvi Parekh, and others. Their art showed a glimpse of Indian society. Churches in India, like Tamil Nadu's Sanctuary of Our Lady of Vailankanni, also have statues of Mary dressed in a traditional saree. These examples show how art and faith traditions can blend. Symbols and images merge, creating new cultures that stand against hate and strict interpretations. Nirendranath Chakraborty, a famous modern poet from Bengal, wrote a well-known poem called "Kolkatar Jishu" (The Jesus of Calcutta).

The lasting tenderness of the mother-child figure, of motherhood and the strong bond of love, is what the Christ child on Madonna's lap represents. This feeling is also seen in the image of Krishna-Yashoda or Devaki. This shared feeling perhaps defines the "culture of love" and explains why this symbol is interpreted in so many ways in art and poetry across India.

Famous Madonna Artworks

There are many famous artworks of the Virgin Mary. The term "Madonna" is often used for images of Mary, even if they were not created by Italian artists. Here are a few examples:

- Golden Madonna of Essen: This is the earliest large sculpture of Mary in Western Europe. It was a model for later wooden sculptures.

- Madonna of humility: This shows Mary sitting on the ground or on low cushions.

- Madonna and Child: A painting by Duccio di Buoninsegna from around 1300.

- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa: This icon in Poland is said to have been painted by St. Luke the Evangelist on a cypress table top from the Holy Family's home.

- Madonna and Child with Flowers: Possibly one of two works started by Leonardo da Vinci.

- Madonna Eleusa: This "tenderness" style has been shown in both Eastern and Western churches.

- Madonna of the Steps: A carved relief by Michelangelo.

- Madonna della seggiola: A painting by Raphael.

- Madonna with the Long Neck: A painting by Parmigianino.

- The Madonna of Port Lligat: The name of two paintings by Salvador Dalí created in 1949 and 1950.

Paintings

- Madonna in Art

-

Madonna and Angels, by Duccio, 1282.

-

Mary and the child shown as a hodegetria. A mosaic icon in a grand style, early 13th century. From Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai, Egypt.

-

Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, by Jan van Eyck, Burgundy, around 1435.

-

Madonna del Granduca, by Raphael, 1505.

-

Madonna of the Pinks, by Raphael, probably before 1507.

-

Madonna and Child Surrounded by Angels by Quentin Matsys, around 1509.

-

Maria Hilf by Lucas Cranach the Elder, around 1530.

-

Virgin Mary by El Greco, around 1600 (at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg).

-

The Virgin in Prayer by Sassoferrato, 1640–1650. At the National Gallery, London.

-

Virgin and Child with Angels and Saints, by Felice Torelli, 17th century.

-

A fresco of a black Madonna and Jesus at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum, Ethiopia.

Statues

-

Black Madonna, Barcelona.

-

Statue outside Moscow's New Tretyakov Gallery.

-

Statue at Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

-

La Conquistadora, Santa Fe, New Mexico, before 1625.

-

Our Lady of Walsingham shrine at Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania).

Manuscripts and Covers

-

Svanhild Evangeliary, an Illuminated manuscript from Essen, 1058–1085.

See Also

- Christian art

- Art in Roman Catholicism

- Mary (mother of Jesus)

- Roman Catholic Marian art

- Pietà

- Nursing Madonna

- Life-giving Spring

- Eleusa icon

- Theotokos

- Icon of the Hodegetria

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- La Conquistadora

- Nativity of Jesus in art

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |