Helicoverpa zea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Helicoverpa zea |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Superfamily: | Noctuoidea |

| Family: | Noctuidae |

| Genus: | Helicoverpa |

| Species: |

H. zea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helicoverpa zea (Boddie, 1850)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Helicoverpa zea, commonly known as the corn earworm, is a type of moth in the family Noctuidae. The young form, called a larva, is a big problem for farmers. This is because it eats many different plants during its larval stage. Because of this, it has many names, like the cotton bollworm and the tomato fruitworm. It also eats many other crops.

This moth lives across the Americas, but not in northern Canada or Alaska. It has become strong against many pesticides. But farmers can control it using special methods. These include deep ploughing, using trap crops, and biological controls.

The corn earworm moth travels long distances at night. It can be carried by the wind for up to 400 kilometers (about 250 miles). Its pupae can go into a resting state called diapause. This helps them survive bad weather, especially in cold places or during dry times.

Contents

Where Corn Earworms Live

The corn earworm lives in warm and mild areas of North America. It cannot survive winter in places like northern Canada or Alaska. Even in the eastern United States, many do not survive cold winters. They live in states like Kansas, Ohio, Virginia, and southern New Jersey. How well they survive depends on how cold the winter is.

These moths often fly from warmer southern areas to northern areas when the weather gets better. They are also found in Hawaii, the Caribbean islands, and most of South America. This includes countries like Peru, Argentina, and Brazil. Cotton earworms have also been seen in China since 2002.

Corn Earworm Life Cycle

Eggs

Female moths lay their eggs one by one on plant hairs or corn silks. The eggs are light green at first. Then they turn yellow and later grey. Each egg is about 0.5 millimeters tall and 0.55 millimeters wide. They hatch after about 66 to 72 hours.

When a larva hatches, it spends most of its time breaking out of its shell. It makes the exit hole bigger than its head. After leaving the shell, the larva makes a silk net around the hole. This helps it escape and find the shell again to eat it. After eating its shell, the larva rests for a few minutes. Then it starts eating the plant around it.

Larvae

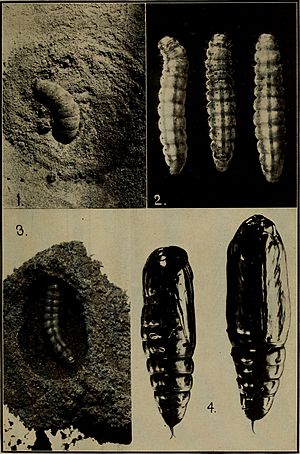

After hatching, the young larvae eat the plant's parts that help it reproduce. They usually grow through four to six stages, called instars. At first, young larvae eat together. This is when they cause the most damage.

As they grow older, the larvae become more aggressive. They may even eat other larvae. This means only one or two larvae are usually found at each feeding spot. Their heads are often orange, and their bodies can be black, brown, pink, green, or yellow. They have many tiny spines. When they are fully grown, the larvae move into the soil. There, they turn into pupae for 12 to 16 days.

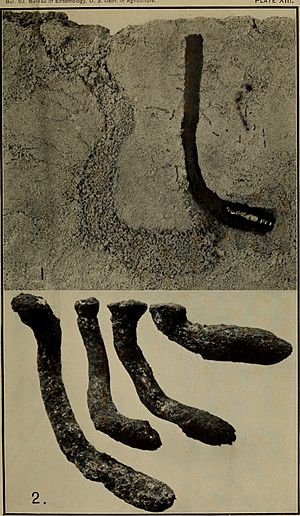

Pupae

Larvae turn into pupae about 5 to 10 centimeters (2 to 4 inches) under the soil. Pupae are brown. They are about 5.5 millimeters wide and 17 to 22 millimeters long. The soil temperature is the most important thing for how fast pupae grow. Cold soil below 0 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) can kill many pupae.

Soil moisture also affects pupae. Too much water (18-25% moisture) can kill them. Not enough water (1-2% moisture) can also cause many deaths.

Adults

Adult moths have yellowish-brown front wings. They have a dark spot in the middle of their body. Their wingspan is about 32 to 45 millimeters (1.2 to 1.8 inches). They can live for over 30 days in perfect conditions. But usually, they live for 5 to 15 days.

These moths are active at night. During the day, they hide in plants. Adult moths drink nectar or other plant liquids from many different plants. Female moths can lay up to 2,500 eggs in their lifetime.

Economic Impact of Corn Earworms

Damage to Crops

The corn earworm is a major pest for farmers. It eats many different crops, including corn. It is one of the most damaging insect pests in North America. The cost of damage from these moths is over $100 million each year. Farmers spend up to $250 million on insecticides to fight them.

These moths cause so much trouble because:

- Females lay many eggs (500 to 3,000).

- Larvae eat many different plants.

- Adults can fly long distances.

- Pupae can pause their growth during bad weather.

How to Control Them

Farmers use different ways to control these pests. Since the 1800s, two main ideas have been used. One tries to reduce the total number of pests. The other tries to protect specific crops. Today, farmers use integrated pest management (IPM). This means using many different methods to control pests.

Some methods include:

- Deep ploughing the soil.

- Destroying pests with machines.

- Using trap crops to lure pests away.

- Applying mineral oil to corn ears to suffocate young larvae.

Pesticides are also used, but corn earworms have become resistant to many of them. Farmers also use biological controls. This means using natural enemies like the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis or tiny worms called nematodes. However, these methods have challenges. The moths are not always affected by the bacterium. Nematodes only work when larvae have turned into pupae in the soil.

Some corn plants have been genetically modified to make the same toxin as the bacterium. These are called Bt-corn.

How Corn Earworms Survive

Natural Enemies

More than 100 types of insects eat H. zea eggs and larvae. For example, the insidious flower bug eats the eggs. This makes it a helpful biological control agent.

Some plants release chemicals when H. zea damages them. These chemicals attract other insects that are parasites. For example, the wasp Cardiochiles nigriceps uses these plant chemicals to find H. zea. When the wasps find damaged plants, they fly around. Then they use their antennae to search for the host. When a female wasp finds a larva, she lays her eggs inside it.

Another important parasitoid wasp is Microplitis croceipes. It lays its eggs inside living caterpillars, including H. zea. If there are many larvae, a fungal pathogen called Nomuraea rileyi can cause a disease outbreak. However, many pupae die not from predators, but from bad weather, collapsing soil chambers, or disease.

Larvae Eating Other Insects

As larvae grow, they become more aggressive. Even with plenty of plants to eat, H. zea larvae will attack and eat other insects. For example, if they find a young Urbanus proteus larva, the corn earworm larva will grab it. It then rolls onto its side and starts eating the other insect from the back. If the U. proteus tries to bite back, the H. zea larva turns it around. It then uses its mandibles to bite the head, killing it. Then, the H. zea larva turns the U. proteus back and eats it all.

Corn earworm larvae prefer to eat other caterpillars over plants. Larvae that grow in dry places are smaller as pupae and take longer to develop. This shows that eating other insects helps them get enough food when conditions are tough.

How Corn Earworms Move

Migration

Helicoverpa zea moths travel at night during certain seasons. Adults fly away when there are not enough good places to lay eggs. For short trips, moths fly low over crops. This flight does not depend much on the wind. For long trips, adults fly up to 10 meters (33 feet) above the ground. They let the wind carry them from one crop to another.

Long-distance flights can happen 1 to 2 kilometers (0.6 to 1.2 miles) high and last for hours. It is common for moths to travel 400 kilometers (250 miles) when carried by the wind. Sometimes, Helicoverpa zea caterpillars are found on produce shipped by air-freight. Most of their activity happens at night. Some moths fly straight up into the air. This helps them get into higher wind systems for long migrations. During mating, males fly fast to find female pheromones.

Diapause

Pupae can enter a special resting state called diapause. This is when their growth stops because of changes in the environment. By doing this, they can survive bad conditions and have more babies later. More pupae go into diapause in colder, northern areas. In warm, tropical places, moths breed all the time. Only a few pupae (2-4%) go into diapause there. In mild and warm regions, most individuals go into diapause. Those that do not, often hatch in late fall and die without having babies. Diapause has also been seen in summer when there is a drought.

What Corn Earworms Eat

Host Plants

Helicoverpa zea eats many different plants. It attacks vegetables like corn, tomato, artichoke, asparagus, cabbage, cantaloupe, collards, cowpea, cucumber, eggplant, lettuce, lima bean, melon, okra, pea, pepper, potato, pumpkin, snap bean, spinach, squash, sweet potato, and watermelon. However, not all these plants are equally good for them. Corn and lettuce are great hosts, but tomatoes are less helpful. Broccoli and cantaloupe are poor hosts. Corn and sorghum are the corn earworm's favorites.

You can spot these moths by certain signs:

- Young corn plants have holes in their leaves.

- Eggs can be found on the silks of larger corn plants.

- Corn silks show signs of being eaten.

- The soft, milky grains at the top of corn cobs are eaten as the corn grows. Usually, only one larva is found per cob.

- Holes are seen in cabbage and lettuce hearts, flower heads, cotton bolls, and tomato fruits.

- Sorghum heads are eaten, and seeds in legume pods are consumed.

Corn

Helicoverpa zea is called the corn earworm because it causes a lot of damage to cornfields. It eats every part of the corn plant, including the kernels. When larvae eat a lot at the tip of the kernels, it can let diseases and mold grow.

Larvae start eating the kernels once they reach their third stage of growth. They can go 9 to 15 centimeters (3.5 to 6 inches) deep into the ear. They go deeper as the kernels get harder. Larvae do not eat the hard kernels. Instead, they bite many kernels, which lowers the quality of the corn for processing.

Soybeans

Helicoverpa zea is the most common and damaging pest for soybeans in Virginia. About one-third of Virginia's soybean fields are treated with insecticides each year. This costs farmers around $2 million. The amount of damage depends on how many pests there are, when they attack, and the plant's growth stage.

Soybean plants can handle a lot of damage without losing too much yield. This depends on soil moisture, planting time, and weather. If the damage happens early, it mostly affects the leaves. Plants can make up for this by growing bigger seeds in the pods that are left. Most damage happens in August when the plants are flowering. Attacks after August cause less damage. This is because many pods have tougher walls that H. zea cannot get through.

Infestations that affect pod formation and seed filling can reduce yields. Since this happens later in the plant's life, they have less time to recover. Female moths are drawn to flowering soybean fields. The worst infestations happen between flowering and when pods are fully grown. Large outbreaks happen when many plants are flowering and many moths are flying. Moths are also attracted to soybeans that are stressed by drought or not growing well. Dry weather makes corn plants dry out quickly, forcing moths to find other plants. Heavy rain also reduces corn earworm numbers. It can drown pupae in the soil, limit moth flight, wash eggs off leaves, and create good conditions for fungal diseases that kill caterpillars.

Mating and Reproduction

Pheromone Production

A special hormone from the female moth's brain controls the production of sex pheromones. This hormone is released into the moth's blood to start pheromone making. A peptide called PBAN (Pheromone Biosynthesis Activating Neuropeptide) helps control pheromone production in moths. It works on the pheromone gland cells using calcium and cyclic AMP.

Even though the time of day affects PBAN release, chemical signals from the host plant are more important. Female Helicoverpa zea in cornfields do not make pheromones at night until they find corn. Certain natural chemicals from corn silk, like the plant hormone Ethylene as a plant hormone#ethylene, make H. zea produce pheromones. Just the presence of corn silk is enough to cause pheromone production. The female moths do not even need to touch the corn. This helps the moths time their mating with when food is available.

After mating, female moths often lose their sex pheromone within two hours. A protein from the male's body, called pheromonostatic peptide (PSP), causes this. Males have evolved this ability because it helps them have more offspring. If a female does not have a sex pheromone, other males will not be attracted to her. This means the female will only have babies from the first male. If a male transfers sperm without these special proteins, the female will still make pheromones, but she will stop calling for mates. This shows that males have evolved ways to control female reproduction.

If females are infected with a virus called Helicoverpa zea nudivirus 2, they produce 5 to 7 times more sex pheromone than healthy females.

Mortality

Mating can have a negative effect on moths. For females, competition for sperm and chemicals from the male can shorten their lives. For males, making sperm and other chemicals also shortens their lives. As moths mate more often, their death rate goes up for both males and females.

Flight Behavior

Males must first sense a female's pheromones to find her. Before flying to find a female, males warm up. They shiver their flight muscles to reach the best temperature for flying, around 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit).

When males smell female pheromones, they warm up faster. They also take off at a lower body temperature than males who smell other chemicals. Warming up to the right temperature leads to better flight. But flying immediately means they might not fly as well. So, there is a trade-off. Helicoverpa zea males exposed to female pheromones shiver less and heat up faster. This behavior is linked to competing for females. It shows how their actions are shaped by their environment.

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Helicoverpa zea para niños

In Spanish: Helicoverpa zea para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |