History of Metz facts for kids

Metz, a historic city in France, has a rich past stretching back over 2,000 years! It has been many things: a Celtic town, an important Gallo-Roman city, a capital for kings, the birthplace of a famous royal family (the Carolingian dynasty), and even a place where Gregorian chant music began. Located in the heart of Europe, Metz has seen many changes, including being part of the Roman Empire, becoming Christian, facing attacks from different groups, experiencing religious wars, the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and even being part of the German Empire and living through World War II.

Contents

Ancient History of Metz

The Celtic Mediomatrici tribe ruled the city from 450 BC. They made it their main town, or oppidum. Metz became a busy trading center for metal and clay pots. When Julius Caesar conquered Gaul in 52 BC, Metz became part of the Roman Empire.

Metz in the Roman Empire

Metz, then called Divodurum, was a strong city with many military roads. It became one of the most important towns in Gaul, even bigger than Lutetia (which is now Paris). The city was rich from selling its wine. It had one of the largest amphitheaters in Gaul. A long aqueduct, about 23 kilometers (14 miles) long with 118 arches, was built in the 2nd century AD. This aqueduct brought water from Gorze to Metz for the public baths, called thermae. You can still see parts of this aqueduct today in towns like Jouy-aux-Arches. You can also visit the remains of the thermae in the basement of the Golden Courtyard museum.

Around the 3rd century AD, groups like the Alemanni and Franks began to attack the city. In 451, the city was attacked and damaged by the Huns led by Attila. Metz was one of the last Roman strongholds to fall. By the end of the 5th century, it was taken over by the Franks.

A Difficult Time in 69 AD

In 69 AD, soldiers of Vitellius were passing through Divodurum on their way to Italy. For reasons that are not fully clear, they killed almost 4,000 people in the city.

How Christianity Came to Metz

People believe that Saint Clement of Metz was the first bishop of Metz. He was supposedly sent by Saint Peter in the 1st century. However, the first bishop whose existence is fully proven was Sperus or Hesperus, who was bishop in 535.

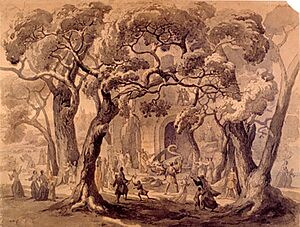

Saint Clement of Metz is famous for a legend where he defeats a local dragon called the Graoully. The story says that the Graoully and many other snakes lived in the Roman amphitheater. Their breath made the air so bad that people in the town were trapped. Clement promised to get rid of the dragon if the people became Christians. After they agreed, Clement went into the amphitheater. When the snakes attacked, he made the sign of the cross, and they immediately became calm. Clement then led the Graoully to the edge of the Seille River. He told the dragon to disappear to a place where there were no people or animals. Many authors see this legend as a symbol of Christianity winning over older, non-Christian beliefs.

Metz: A Capital for Kings

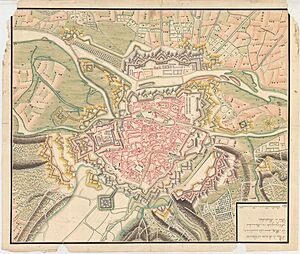

Capital of the Austrasia Kingdom

From the time of King Sigibert I, Metz was often where the Merovingian kings of the Austrasia kingdom lived. When the Carolingian family became kings, they still liked Metz. This was because their ancestors, Saint Arnuff and Chlodulf, had been bishops of Metz. Emperor Charlemagne thought about making Metz his main capital, but he chose Aachen instead. His sons, King Louis the Pious and Bishop Drogo of Metz, were buried in the Basilica of Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains in 840 and 855.

Capital of the Lotharingia Kingdom

After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, Metz became the capital of the Kingdom of Lotharingia. This kingdom was ruled by Emperor Lothair I. After his son, King Lothair II, died, the kingdoms of East Francia and West Francia fought over Lotharingia and its capital. In 869, Charles the Bald was crowned king of Lotharingia in Metz.

In 910, Metz became part of East Francia and later the Holy Roman Empire. This gave the city some independence. By 959, Metz was the capital of Upper Lotharingia, which became known as Lorraine. During this time, the Bishops of Metz gained more political power. The Prince-Bishops became independent from the Dukes of Lorraine, making Metz their capital.

In 1096, Metz saw a difficult time for its Jewish community during the First Crusade. Some crusaders entered Metz, and some Jewish people were forced to change their religion.

The Carolingian Renaissance in Metz

Metz was an important center for culture during the Carolingian Renaissance. Gregorian chant music was created in Metz in the 8th century. It combined local Gallican music with old Roman songs. This music is still used today and is the oldest form of music still sung in Western Europe. Bishops of Metz, like Saint-Chrodegang, helped spread this music. The Metz chant added two important things: it fit the music into an ancient Greek system and invented a new way to write music using neumes. Metz was also a key place for making beautiful illuminated manuscripts, like the Drogo Sacramentary.

-

Map of the Merovingian Austrasia kingdom (darkest green). Metz was its capital from 511 to 751.

-

The basilica and former church of Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains was important for the start of Gregorian chant.

Metz: A Free Imperial City

In 1189, Metz became a Free Imperial City. This meant the bishops had much less power over the city. The bishops moved away, and the citizens, called burgesses, created their own government, a republic.

The Messin Republic

The Republic of Metz had three main parts: a Head-Alderman who represented the city, a group of 13 aldermen who advised, and a House of Burgesses who gave their opinions. Over time, the government changed to an oligarchy, where 21 aldermen ruled the city, and the Head-Alderman was chosen by them. This Republic of Metz lasted until the 15th century. It was a very successful time, and Metz was known as "Metz the Rich." The city was a major banking center, first run by Jewish bankers and then by the Lombards. Today's Saint-Louis square used to be a place for money changers and trade fairs.

The Republic of Metz often had to fight to stay free. In 1324, it fought against the Dukes of Luxembourg and Lorraine in the War of Metz, where cannons were used early on. It also fought against Archbishop Baldwin von Luxemburg of Trier. In 1363 and 1365, it fought against English groups. In 1444, it faced Duke René and King Charles VII of France. In 1473, it fought Duke Nicholas I of Lorraine. Because it stayed independent, Metz was called "The Maid" and "The Unviolated."

Emperor Charles IV held important meetings in Metz in 1354 and 1356. During one of these, the Golden Bull was issued, which set important rules for the Holy Roman Empire. The rulers of Metz wanted to avoid paying imperial taxes and attending imperial meetings. This caused problems between Metz and the other states of the Empire, especially during the religious and political troubles of the Schmalkaldic War.

In 1546, the French writer François Rabelais came to Metz after facing trouble for his ideas. While there, he wrote his fourth book, describing a parade in the city with a statue of the Graoully dragon.

-

The building of the Gothic Saint-Stephen Cathedral began in 1220. It is the main church of the Catholic Diocese of Metz.

Metz Joins the Kingdom of France

In 1552, King Henry II of France and some German princes signed the Treaty of Chambord. This meant Metz became part of France. The people of Metz accepted this peacefully. Emperor Charles V tried to take Metz back by force. He attacked the city in 1552–1553. But his troops were defeated by the French army, led by Francis, Duke of Guise. Metz stayed French. A 13th-century bridge castle, the Porte des Allemands (German Gate), was very important in defending the city during this attack. You can still see it today, and even bullet marks from the muskets used during the siege!

Under French rule, big changes happened to the Republic of Metz. Aldermen still ran the city, but a Royal Governor, representing the king, appointed them. The Bishops also returned to Metz. Later, other officials were sent to make sure the king's power was followed. This ended the Republic of Metz in 1634. In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia officially recognized Metz as part of France. The city became the capital of the Three Bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun. Metz was now a very important fortified town for France. Strong forts were built by famous engineers like Vauban and Cormontaigne.

The French Revolution in Metz

Between 1736 and 1761, Duke of Belle-Isle helped modernize the center of Metz. He hired architect Jacques-François Blondel in 1755 to make the town square beautiful. They built the city hall, the parliament building, and housing for the guards. He also helped develop the Royal Governor's palace and an opera house. In 1760, he created the National Academy of Metz, which is still active today.

During the 18th century, people in Metz embraced new ideas from the Enlightenment and later the French Revolution. In 1775, Lafayette met important people in Metz and decided to support the American Revolutionary War. Also, future revolutionary leader Maximilien de Robespierre and abolitionist Abbé Grégoire were honored by the National Academy of Metz. They wrote essays about important topics like fairness and helping people. When France created new departments, Metz became the capital of the Moselle Department. General François Christophe Kellermann led the local army during the French Revolutionary Wars. They won an important battle at Battle of Valmy against the Prussian troops. The French Revolution also brought hard times. A guillotine was set up for executions in front of the opera house, in a square then called Place de l'égalité (Equality Square). Today, it's called Place de la comédie.

Metz Under French Empires

Later, Metz was attacked by a group of armies during the 1814 campaign against Napoleon's France. But the attackers could not take the city, which was defended by General Pierre François Joseph Durutte and his army. In 1861, during the Second French Empire, Metz hosted a big international fair in the Place de la république and the Esplanade gardens.

-

An example of the work by Jacques-François Blondel, who helped modernize the center of Metz.

Metz Under German Rule (First Time)

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871)

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, Metz was the main base for the French army led by General Bazaine. After several battles, Bazaine and his army retreated into Metz's defenses. After many months of being surrounded, they surrendered. During the siege, the first airmail was sent from the city by Doctor Julien-François Jeannel using a balloon. French officer Louis Rossel, who helped defend Metz, later joined the Paris Commune. He was against General Bazaine's decision to surrender Metz to the Germans.

Metz as a German Garrison Town

After the Treaty of Frankfurt in 1871, Metz became part of the new German Empire. It was part of the Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine, which was directly managed by the German government from Berlin. Metz became the capital of the German part of Lorraine. The local parliament for Lorraine also met in Metz.

The city remained a very important military location. The Germans built new fortified lines around Metz. Parts of the old medieval walls were taken down to allow the city to grow. A new area called the Imperial Quarter was built. Architects, guided by Emperor Wilhelm II, had to plan this new district carefully. It needed to meet military needs, especially for a possible war between Germany and France. For example, the Metz railway station was directly connected to Berlin by a special railway line. At the same time, the new district was meant to show how modern and lively the city was, with fancy homes for the wealthy. Emperor Wilhelm II often stayed in Metz in his headquarters in this new district.

Between Wars: Metz Returns to France

After the armistice with Germany ended First World War, the French army entered Metz in November 1918. Philippe Pétain received his special marshal's staff from French President Raymond Poincaré and Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau in the Esplanade garden. The city officially returned to France under the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Second German Annexation: World War II

However, after the Battle of France in 1940 during Second World War, the city was again taken over by Nazi Germany. It became part of a German region called Westmark. As a symbol of German control, Chancellor Adolf Hitler celebrated Christmas 1940 in Metz. But most local people did not like the German occupation. Many French Resistance groups were active around Metz, like the Mario and Derhan groups. They collected weapons, handed out flyers, helped prisoners, and carried out sabotage. Some resistance fighters were held and tortured in the Fort of Queuleu in Metz. Jean Moulin, a famous resistance leader, died in Metz's railway station while on a train to Germany. In 1944, the U.S. Third Army, led by General George S. Patton, attacked the city. The German forces defended it strongly. The Battle of Metz lasted several weeks. Metz was finally captured by the Americans in November 1944. After the war, the city returned to France.

Metz Today: After the War

In the 1950s, Metz was chosen as the capital of the new Lorraine region. With the creation of the European Communities (which later became the European Union), Metz became a central place in the wider European region. In 1979, Metz hosted an important meeting of the French Socialist Party. During this meeting, François Mitterrand, who would later become French President, won the nomination for the 1981 French presidential election. Later, Pope John Paul II held a Mass in the Saint-Stephen Cathedral during his visit to Metz in 1988. In his speech, he spoke about the importance of European unity during the Cold War. In 2010, Metz opened a branch of the French National Museum of Modern Art, called the Centre Pompidou-Metz. It was designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban and opened by French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

See also

- Timeline of Metz

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |