History of Roman and Byzantine domes facts for kids

Domes were a special part of buildings in Ancient Rome and the Byzantine Empire. These round roofs influenced many styles, from Russian and Ottoman architecture to the Italian Renaissance and modern buildings.

Most domes were shaped like half-spheres. But some were octagonal (eight-sided) or segmented (like slices of a pumpkin). Their design and use changed a lot over hundreds of years. Early domes often sat right on the walls of round rooms. They had a central hole called an oculus for light and air. Later, in the Byzantine period, special triangular supports called Pendentives helped domes sit over square rooms.

We only know about early wooden domes from old writings. But the Romans used wooden molds (called formwork) and concrete to build huge domes. One early example is the "Temple of Mercury" bath hall in Baiae. Emperor Nero started using domes in palaces in the 1st century. These domed rooms were often used for banquets or important meetings.

The Pantheon's dome, built in the 2nd century, is the most famous Roman dome. It was made of concrete and might have been a meeting hall for Emperor Hadrian. Starting in the 3rd century, imperial tombs, like the Mausoleum of Diocletian, also had domes. Some smaller domes were built using ceramic tubes instead of wooden molds. But by the 4th and 5th centuries, light bricks became the preferred building material. Brick ribs made domes thinner and allowed for windows in the supporting walls, so an oculus was no longer needed for light.

Christian baptisteries (places for baptisms) and shrines (holy places) started having domes in the 4th century. Examples include the Lateran Baptistery and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Emperor Constantine's octagonal church in Antioch might have inspired similar buildings for centuries. The first domed basilica (a type of church) might have been built in the 5th century in southern Turkey. But it was Emperor Justinian in the 6th century who made domed churches common across the eastern Roman Empire. His famous churches, Hagia Sophia and the Church of the Holy Apostles, inspired many others.

Churches shaped like a cross with domes at their center became popular in the 7th and 8th centuries. Examples include Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki. Supporting a dome with barrel vaults (rounded ceilings) on all four sides became the standard way to build them. After the 9th century, domes were often built higher up on round or many-sided walls called drums, which had windows. In later times, smaller churches usually had smaller domes, often less than 6 meters (20 feet) wide. The "cross-in-square" plan, with one dome in the middle or five domes in a pattern like a dice (quincunx), was very popular from the 10th century until Constantinople fell in 1453.

Contents

- How Roman Domes Were Built

- Byzantine Dome Design

- History of Domes

- Early Roman Domes

- Domes in the First Century AD

- Domes in the Second Century AD

- Domes in the Third Century AD

- Domes in the Fourth Century AD

- Domes in the Fifth Century AD

- Domes in the Sixth Century AD

- Domes in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries AD

- Domes in the Ninth Century AD

- Domes in the Tenth Century AD

- Domes in the Eleventh Century AD

- Domes in the Twelfth Century AD

- Domes in the Thirteenth Century AD

- Domes in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries AD

- How Domes Influenced Other Cultures

- Images for kids

- See also

How Roman Domes Were Built

Roman architecture used rounded arches, vaults, and domes. This was possible because they used concrete and brick. By changing the weight of the materials in the concrete, they could make the top layers lighter.

Building concrete domes needed expensive wooden molds (formwork). These molds had to stay in place while the concrete dried. They often had to be destroyed to be removed. Molds for brick domes didn't need to stay as long and could be reused. Roman concrete was laid by hand in horizontal layers against the wooden molds. The Romans used rubble as a base, but lighter materials at the top of the dome helped reduce stress. Sometimes, empty vases or jugs were hidden inside to make the dome lighter.

Roman domes were used in baths, villas, palaces, and tombs. They often had oculi (central holes). Most were shaped like half-spheres and were often hidden from the outside. To support large domes, the walls beneath them were built very thick. Sometimes, a conical or polygonal roof was built over the dome. Other dome shapes included shallow "saucer domes" and "ribbed domes." Stone or brick ribs were usually hidden inside the dome.

Domes were often found in imperial palaces and cities connected to the emperor. They were also common over garden pavilions. Some old Roman coins show wooden, bulbous domes covered in metal on towers in the eastern part of the empire. After the western Roman Empire declined, dome building slowed down in the west.

Byzantine Dome Design

In Byzantine architecture, a new support system used four arches with pendentives (curved triangles) between them. This allowed domes to be built over square rooms, which was more practical. Pendentives helped spread the dome's weight to just four points.

Until the 9th century, Byzantine domes were low and had thick supports. They didn't stick out much from the building's exterior. After the 9th century, domes became taller and sat on polygonal (many-sided) drums. These drums were often decorated with columns and arches. By the 12th century, outside dome decoration became even fancier. Many buildings had multiple domes.

Domes were important for baptisteries, churches, and tombs. They were usually half-spherical and had windows in their drums. Dome roofs were made from simple ceramic tiles or more expensive lead sheets. Domes and drums often had wooden rings inside to help them stay strong and build faster. Metal clamps and chains also helped stabilize the buildings. Wooden belts at the base of domes helped walls during earthquakes, but the domes themselves could still collapse. Ribbed or "pumpkin" domes were common. These could be built with less wooden support.

History of Domes

Early Roman Domes

Roman baths were very important for developing domes. Small domes from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC can be seen in Pompeii. These domes were cone-shaped. According to the Roman writer Vitruvius, bronze discs under an oculus could control the temperature in warm rooms. Domes were perfect for hot rooms in baths because they helped spread heat evenly. However, domes weren't widely used until the 1st century AD.

Old writings describe a wooden dome in a birdcage (aviary) that rotated. Wooden domes could span very wide areas. Their early use might have inspired the building of large stone domes. Complex wooden molds were needed to support domes during construction.

Domes became huge during the Roman Imperial period. The "Temple of Mercury" in Baiae is an early example. It was actually a concrete pool for a bath. It dates to the late Roman Republic or the time of Emperor Augustus. This makes it the first large Roman dome. It has a central oculus and four square skylights. This dome is 21.5 meters (70 feet) wide. It is the largest known dome built before the Pantheon. It is also the oldest concrete dome still standing.

Domes in the First Century AD

Dome building grew under Emperor Nero and the Flavian dynasty in the 1st century AD. Important halls in palaces began to feature domes. These were used for state banquets or as throne rooms.

Emperor Nero's amazing palace, the Domus Aurea (Golden House), shows important dome development. A large octagonal room had an octagonal dome that then became a round dome with an oculus. This is the first known dome in Rome itself. The Domus Aurea was built after 64 AD. Its dome was over 13 meters (43 feet) wide. The dome was made of concrete, and the oculus was brick. Walls around the room supported the dome. This allowed for large openings and made the room very bright. The dome might have been covered by a fabric canopy. The oculus was very large. It might have held a light structure or a rotating dome, as old writings suggest.

According to the writer Suetonius, the Domus Aurea had a dome that spun like the sky. Recent discoveries suggest this might have been a rotating dining hall. The palace was so fancy that it was abandoned after Nero's death. Public buildings like the Baths of Titus and the Colosseum were built on its site.

Emperor Domitian also built domes. His villa at Albano Laziale has a 16.1-meter (53-foot) wide dome. His palace on the Palatine Hill used domes over square rooms. It had three domes over walls with curved and rectangular openings.

Domes in the Second Century AD

Under Emperor Trajan, domes and half-domes were common in Roman buildings. This was likely due to his architect, Apollodorus of Damascus. The Baths of Trajan had two round rooms 20 meters (66 feet) wide.

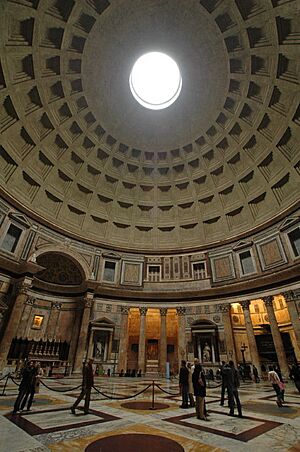

The Pantheon in Rome is the most famous and best-preserved Roman dome. Emperor Hadrian completed it. Its dome is more than twice as wide as any earlier dome. Some believe Apollodorus designed it. The Pantheon's dome is 43.4 meters (142 feet) wide. It rests on a circular wall (rotunda) 6 meters (20 feet) thick. This rotunda has many arches and empty spaces to lighten the load. The dome's only opening is a 9-meter (30-foot) wide oculus at the top. This oculus provides light and air.

The dome's shallow coffers (sunken panels) are mostly for decoration. The concrete used in the dome gets lighter as it goes up. This greatly reduces stress on the structure. The Pantheon is a great example of how Roman concrete changed architecture. However, cracks appeared early on. This suggests the dome acts more like a series of arches than a single solid unit. The Pantheon's roof was originally covered with gold-plated bronze tiles. These were removed in 663 AD.

The Pantheon's purpose is still debated. It was unusual for a temple. Its name means "all gods," but it wasn't officially a temple to all gods. It looks more like imperial palaces or baths. Hadrian might have used it as a court. The Pantheon remained the largest dome in the world for over 1,000 years. It is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.

Emperor Hadrian's villa in Tivoli shows complex dome shapes. The Small Thermal Baths had an octagonal domed hall. Segmented domes, made of curved or alternating curved and flat sections, also appeared under Hadrian. These domes needed complex wooden supports. Hadrian was an amateur architect. Trajan's architect, Apollodorus, supposedly made fun of Hadrian's "pumpkin" domes. This insult may have led to Apollodorus's exile and death.

In the mid-2nd century, huge domes were built near Naples for bath complexes. The "Temple of Venus" had a collapsed dome 26.3 meters (86 feet) wide. The "Temple of Diana" had a larger, half-collapsed dome 29.5 meters (97 feet) wide. The "Temple of Apollo" was even larger, over 36 meters (118 feet) wide.

In North Africa, a new technique developed using interlocking hollow ceramic tubes. These tubes formed a permanent support for concrete domes, avoiding wooden molds. This method spread mainly in the western Mediterranean.

Pendentive domes were known in the 2nd century Roman architecture, though rarely used. They would become much more common in the Byzantine period.

Domes in the Third Century AD

The large rotunda of the Baths of Agrippa in Rome was rebuilt in the early 3rd century.

In the 3rd century, imperial tombs (mausolea) began to be built as domed rotundas. Christian and pagan domed mausolea differed. Pagan ones were two stories, dimly lit, with a crypt below. Christian ones had a single, well-lit space and were usually attached to a church.

Examples include the brick dome of the Mausoleum of Diocletian. The Villa Gordiani also has dome ruins. The Mausoleum of Diocletian used a "stepped squinches dome" pattern. This pattern was popular in the Middle East. Diocletian's Palace also had a domed rotunda, possibly a throne room.

Stone domes were less common in Roman provinces. The "Temple of Venus" at Baalbek had a stone dome 10 meters (33 feet) wide.

The technique of building lightweight domes with interlocking hollow ceramic tubes continued to develop in North Africa and Italy. By the 4th century, this method was used in early Christian buildings in Italy. The dome of the Baptistry of Neon in Ravenna is an example.

Domes in the Fourth Century AD

In the 4th century, Roman domes became more common. This was due to better building techniques, including the use of brick ribbing. The "Temple of Minerva Medica" used brick ribs and lightweight concrete. Building materials slowly changed from stone or concrete to lighter brick. Ribs made domes thinner and allowed for windows in the walls. The Mausoleum of Santa Costanza has windows under its dome.

The 24-meter (79-foot) dome of the Mausoleum of Galerius was built around 300 AD. It was later turned into a church. Emperor Constantine built the "Domus Aurea" (Golden Octagon) in Antioch in 327. It had a domed roof, probably made of wood and covered with gilded lead. This church may have been a model for later octagonal churches.

Constantine also built the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem around 333. It was a large basilica with an octagonal dome over the cave where Jesus was said to be born.

Round or octagonal buildings became popular for baptisteries and reliquaries. The octagonal Lateran Baptistery might have been the first. The style spread in the 5th century. The brick Church of St. George in Sofia was originally a bath hall. It was converted into a church in the mid-5th century. It is a round building with four curved niches. Its dome is about 14 meters (46 feet) high.

In the mid-4th century in Rome, domes were built as part of the Baths of Constantine. Domed tombs for rich families were built next to churches.

Christian tombs and shrines developed into "centralized churches" with a dome over a raised central area. The Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, built by Constantine's successor Constantius, combined a church with a central shrine. It had a central rotunda with Constantine's tomb. The center might have had a wooden dome covered in bronze and gold.

The largest early Christian church, Milan's San Lorenzo Maggiore, was built in the mid-4th century. It might have had a light dome, perhaps of timber. The original dome collapsed in 1103 and was rebuilt.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem likely had a wooden dome over the shrine by the late 4th century. The dome was about 21 meters (69 feet) wide. It was destroyed in 1009 and rebuilt in 1048. The current dome is from 1977.

Domes in the Fifth Century AD

By the 5th century, small domed churches shaped like a cross were found across the Christian world. Examples include the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. Small brick domes are also found in the towers of Constantinople's early 5th-century walls. Underground cisterns in Constantinople, like the Cistern of Philoxenos, had grids of columns supporting small domes. The square space with a dome on pendentives became a basic unit in early Byzantine architecture.

The last imperial domed tomb in Rome was for Emperor Honorius, built in 415. It was demolished in 1519. The last domed church in Rome for centuries was Santo Stefano al Monte Celio around 460. It had an unusual plan and a 22-meter (72-foot) wide dome. Domes would not be built in Rome again until 1453.

With the end of the Western Roman Empire, domes became a key feature of the Eastern Roman Empire's church architecture. Churches changed from timber-roofed basilicas to vaulted churches between the late 5th and 7th centuries. The first known domed basilica might have been a church at Meriamlik in southern Turkey, built between 471 and 494.

Domes in the Sixth Century AD

The 6th century was a turning point for domed churches. Emperor Justinian used the domed cross design on a grand scale. His architects made the domed brick-vaulted central plan standard in the Roman east. This difference from the Roman west marks the beginning of "Byzantine" architecture.

The earliest of Justinian's domed buildings might be the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, finished by 536. Its dome rests on an octagonal base and is divided into sixteen sections.

After the Nika riots destroyed much of Constantinople in 532, Justinian rebuilt the churches of Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene. Both were rebuilt as domed basilicas. The Hagia Sophia was built between 532 and 537. It is an original and innovative design. Earthquakes have caused the dome to collapse partially three times. The original dome was bolder than the current one. The writer Procopius said the original dome seemed to "cover the space with its golden dome suspended from heaven."

The current central dome is about 750 mm (30 inches) thick. It is about 32 meters (105 feet) wide and has 40 ribs. Windows at its base help prevent cracks. Iron clamps helped stabilize the dome. The dome and its supports rest on four large arches and four piers. Two huge half-domes are on opposite sides of the central dome. The Hagia Sophia is considered one of the greatest buildings in the world.

The city of Ravenna, Italy, also had important domed buildings. The Basilica of San Vitale, completed in 547, has a terracotta dome. Hollow amphorae (jars) were fitted inside to make the dome lightweight. This dome is 18 meters (59 feet) wide.

Justinian also rebuilt the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople between 536 and 550. It was shaped like a cross with a central dome and four smaller domes. The central dome had windows at its base. This church was later destroyed. Justinian's Basilica of St. John at Ephesus and Venice's St Mark's Basilica were inspired by Holy Apostles.

The Golden Triclinium (Chrysotriklinos) of the Great Palace of Constantinople was an audience hall and chapel for the Emperor. It had a "pumpkin dome" with sixteen windows. It was begun under Emperor Justin II and improved by later rulers.

Domes in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries AD

The period of Byzantine Iconoclasm (7th to 9th centuries) was a time of change. The cathedral of Sofia combines a barrel-vaulted cross-shaped church with a central dome.

Earthquakes and invasions in the 7th to 9th centuries led to more masonry domes and experiments with vaults over churches in Anatolia. The Church of St. Nicholas at Myra had a dome on pendentives over its main area.

Byzantine domes became part of more modest new buildings as the empire's resources declined. The Hagia Irene church was rebuilt after an earthquake in 740. Its central dome was replaced with one on a high, windowed drum. Bracing the dome with wide arches on all four sides made the structure more stable. This "cross-domed unit" became standard in later Byzantine churches.

A small monastic community may have developed the "cross-in-square" church plan during this time. This plan led to smaller churches.

Domes in the Ninth Century AD

From the 9th century onward, domed churches replaced timber-roofed basilicas as the standard. In the Middle Byzantine period, domes usually highlighted separate functional spaces. Domes on circular or polygonal drums with windows became the standard style.

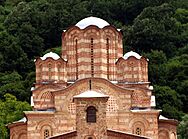

The "cross-in-square" plan, with one dome in the middle or five domes in a pattern like a dice (quincunx), became very popular. The Nea Ekklesia of Emperor Basil I, built around 880, had five domes. The five-domed design of St. Panteleimon at Nerezi (1164) is thought to be based on the Nea Ekklesia.

Domes in the Tenth Century AD

More complex church plans appeared in the Middle Byzantine period. The Theotokos of Lips in Constantinople, built around 907, had four small chapels that might have been domed.

The "cross-in-square" plan was the most common church plan from the 10th century until 1453. This plan, with four columns supporting the dome, worked best for domes less than 7 meters (23 feet) wide. Most Byzantine domes from the 10th to 14th centuries were less than 6 meters (20 feet) wide. For wider domes, builders used piers instead of columns and added more support.

The palace chapel of the Myrelaion in Constantinople, built around 920, is a good example of a cross-in-square church. The earliest cross-in-square church in Greece is the Panagia church at Hosios Loukas, from the late 10th century. This type of church was used for many purposes, including homes, parishes, monasteries, palaces, and tombs.

The unique "rippling eaves" design for dome roofs began in the 10th century. In mainland Greece, round or octagonal drums became very common.

Domes in the Eleventh Century AD

In Constantinople, drums with twelve or fourteen sides were popular from the 11th century. Rock-cut churches in Cappadocia, like Karanlik Kilise, had shallow domes without drums because they were inside caves.

The "domed-octagon" plan is a type of cross-in-square. The earliest example is the katholikon at Hosios Loukas, with a 9-meter (30-foot) wide dome built in the early 11th century. This dome had no drum and was supported by eight piers. The use of squinches (arches across corners) to connect the octagon to the dome might show influences from Arab or Caucasian architecture. The smaller monastic church at Daphni (c. 1080) uses a simpler version of this plan.

The katholikon of Nea Moni, built between 1042 and 1055, had a nine-sided, ribbed dome. This dome collapsed in 1881 and was rebuilt. This unique technique in Byzantine architecture is called the "island octagon" type.

Domes in the Twelfth Century AD

Some larger Byzantine buildings in the 12th century needed stronger dome supports than the slender columns of the cross-in-square type. Churches like Kalenderhane Mosque and Gül Mosque had domes larger than 7 meters (23 feet). They used piers in their plans, which had been out of style for centuries. The "atrophied Greek cross plan" also provided more support for a dome by using four piers from the corners of a square room. This design was used in the Chora Church in Constantinople after an earthquake.

The Pantokrator monastic complex (1118–36) had three churches. The south church had a ribbed dome. The middle church had two oval domes. One covered an imperial tomb, and the other a worship space.

A written account from the late 12th century describes a Persian-style dome in an imperial palace in Constantinople. This "Mouchroutas Hall" might have been built to ease tensions between the Byzantine emperor and the Sultanate of Rum.

Domes in the Thirteenth Century AD

The Late Byzantine Period (1204 to 1453) saw changes in church design. The empire was fragmented, leading to regional innovations.

The church of Hagia Sophia in the Empire of Trebizond (1238–1263) had a variation of the quincunx plan. Its brick pendentives and dome drum were Byzantine in style.

After 1261, new churches in Constantinople were often additions to existing monasteries. This led to buildings with many domes arranged unevenly on their roofs. This might have copied the earlier Pantokrator complex.

In the Despotate of Epirus, the Church of the Parigoritissa (1282–9) is a complex example. It has a domed octagon core and a domed walkway. Its upper level has five domes.

Domes in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries AD

In Mystras, several churches had domes over their galleries, creating a five-domed cross-in-square plan over a basilica. The Aphentiko at Brontochion Monastery (c. 1310–22) and the Pantanassa Monastery (1428) are examples. The Pantanassa also included Western elements, like hidden domes in its porch.

In Thessaloniki, a unique church dome style developed in the early 14th century. It had a polygonal drum with rounded columns at the corners. The five domes of the Hagioi Apostoloi (c. 1329) make it a late Byzantine example. The Gračanica monastery in Serbia (c. 1311) also shows this style. Its architects likely came from Thessaloniki.

An old account from the 15th century mentions an abandoned domed hall in Constantinople. It was said to have the sun, moon, and stars moving like in the sky.

How Domes Influenced Other Cultures

Armenia

Constantinople's influence spread far and wide. Armenia, located between the Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian empires, was influenced by both. The relationship between Byzantine and Caucasus architecture is not fully clear. Georgia and Armenia built many central, domed buildings in the 7th century. After a break during Arab invasions, dome building grew again.

Armenian church domes were first made of wood. Etchmiadzin Cathedral (c. 483) originally had a wooden dome. This was replaced with stone in 618. Stone domes became standard after the 7th century. Some later stone examples looked like wooden designs. Armenian churches often combined central and long plans. Domes were supported by squinches (used in Sasanian Empire) or pendentives (like Byzantium). An 11th-century Armenian source says an Armenian architect, Trdat, rebuilt the dome of Hagia Sophia after an earthquake in 989.

The Balkans

In the Balkans, domed architecture might show Byzantine influence. Or, in 9th-century Dalmatia, it might be a revival of earlier Roman tomb styles. This interest in Roman models might have been about religious differences between Constantinople and Rome. Examples include churches in Kotor, Split, and Zadar. The Church of Sv. Donat in Zadar was originally domed. It might have been a palace church.

The architecture of the First Bulgarian Empire is debated. The Round Church in Preslav was a domed palace chapel. Its features resemble 3rd and 4th century Roman tombs.

The Rus'

Byzantine architecture came to the Rus' people in the 10th century. Churches after Prince Vladimir of Kiev converted were modeled after Constantinople's, but made of wood. The Russian onion dome came later. By the 12th century, masonry domes in Kiev and Vladimir-Suzdal were similar to Byzantine ones. They were slightly pointed, like a "helmet."

The Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev (1018–37) was unique with thirteen domes, representing Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. These domes have since been changed. Bulbous onion domes on tall drums developed in northern Russia. This might be due to heavy snow and ice. The central dome of the Cathedral of St. Sophia (1045–62) in Novgorod shows a transitional stage.

Romanesque Europe

In Romanesque Italy, Byzantine influence is clear in Venice's St Mark's Basilica (c. 1063). It is also seen in domed churches in southern Italy. In Norman Sicily, architecture mixed Byzantine, Islamic, and Romanesque styles. The dome of the Palatine Chapel (1132–43) in Palermo was decorated with Byzantine mosaics.

The unusual use of domes on pendentives in many Romanesque churches in the Aquitaine region of France suggests Byzantine influence. St. Mark's Basilica was modeled after the lost Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles. Périgueux Cathedral in Aquitaine (c. 1120) also has five domes on pendentives.

Orthodox Africa and Europe

The Throne Hall of Dongola, built in the 9th century in Old Dongola, had a small dome. It copied the audience halls of Byzantine emperors. Bulgarian tsars had similar halls.

Byzantium's neighboring Orthodox countries in Europe became important architectural centers. Churches in Nesebar, Bulgaria, are similar to those in Constantinople. The style of churches like Christ Pantocrator is similar to Constantinople examples. After the Gračanica monastery was built, Serbian architecture used the "Athonite plan." In Romania, Wallachia was influenced by Serbian architecture. Moldavia had more original designs, like the Voroneț Monastery with its small dome. Moscow became the most important architectural center after Constantinople fell in 1453. The Cathedral of the Assumption (1475–79) in the Kremlin was designed in a traditional Russian style by an Italian architect.

Italian Renaissance

Italian Renaissance architecture combined Roman and Romanesque styles with Byzantine structures. This included domes with pendentives over square spaces. The Cassinese Congregation used windowed domes in the Byzantine style. They often arranged them in a quincunx pattern.

The technique of using wooden tension rings inside domes to prevent damage, often credited to Filippo Brunelleschi, was common in Byzantine architecture. Double shells for domes, used in the Renaissance, also came from Byzantine practice. The dome of the Pantheon was a symbol of Rome's past. It was studied and copied, inspiring domes in Western architecture for centuries. Examples include St. Peter's Basilica and the Library Rotunda of the University of Virginia.

Ottoman Empire

Ottoman architecture adopted and developed the Byzantine dome. One type of mosque was modeled after Justinian's Church of Sergius and Bacchus. The dome and half-domes of the Hagia Sophia were especially copied and improved. This "universal mosque design" spread worldwide. The mosque of Beyazit II was the first Ottoman mosque to use a dome and half-dome design like Hagia Sophia. Other Ottoman mosques, like the Süleymaniye Mosque (1550–57), also used this style. When Mimar Sinan built the Selimiye Mosque (1569–74), he used a more stable octagonal support structure.

Modern Revival

A Byzantine revival style appeared in the 19th and 20th centuries. An early example in Russia was the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (1839–84). This style became popular after Greece and the Balkans gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. It spread across Europe and North America, being most popular between 1890 and 1914. Examples include St Sophia's Cathedral (1877–79) and Westminster Cathedral (begun 1895) in London. The throne room of Neuschwanstein Castle (1885–86) in Bavaria also used this style.

In the late 19th century, the Hagia Sophia became a model for Greek Orthodox churches. In southeastern Europe, large national cathedrals used Neo-Classical or Neo-Byzantine styles. Sofia's Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and Belgrade's Church of Saint Sava used Hagia Sophia as a model. Synagogues in the United States also used the Byzantine Revival style in the 1920s.

In the United States, Greek Orthodox churches from the 1950s often used a large central dome with a ring of windows, like Hagia Sophia. Examples include Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church (1961) designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. This trend continued into the 1960s and 1970s.

Images for kids

-

The circular oculus of the Pantheon, at the center of the domed ceiling

-

Ruins at Villa Gordiani

-

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna

-

The Church of the Parigoritissa in Arta, Greece

-

The Gračanica monastery in Kosovo, built under the medieval Kingdom of Serbia

-

The Hosios Loukas Panagia church near Distomo, Greece

-

The katholikon of the monastery of Hosios Loukas near Distomo, Greece

-

Ravanica Monastery, Serbia

-

Cathedral of the Assumption, Moscow

See also

In Spanish: Historia de las cúpulas romanas y bizantinas para niños

In Spanish: Historia de las cúpulas romanas y bizantinas para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |