Hugo Sperrle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hugo Sperrle

|

|

|---|---|

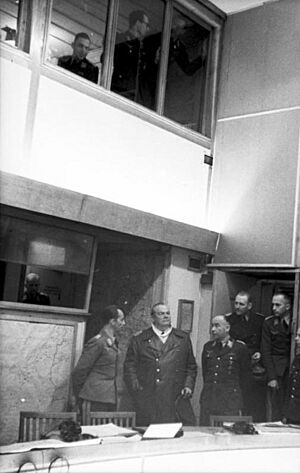

Hugo Sperrle in 1940

|

|

| Born | 7 February 1885 Ludwigsburg, German Empire |

| Died | 2 April 1953 (aged 68) Munich, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1903–1944 |

| Rank | Generalfeldmarschall |

| Unit | Condor Legion |

| Commands held | 1 Fliegerdivision Luftflotte 3 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross Spanish Cross |

Wilhelm Hugo Sperrle (born February 7, 1885 – died April 2, 1953), also known as Hugo Sperrle, was a German military leader. He was an aviator in World War I and later became a high-ranking officer, a Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal), in the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) during World War II.

Sperrle joined the German Army in 1903. He started in the artillery but later joined the air service in 1914. He became an observer and then a pilot. By the end of World War I, he was a Captain in charge of an aerial reconnaissance unit. After the war, he continued to serve in the military. When the Nazi Party came to power, he joined the newly formed Luftwaffe. He played a key role in the Spanish Civil War and later in major battles of World War II, including the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain.

Early Life and World War I Service

Hugo Sperrle was born in Ludwigsburg, Germany, on February 7, 1885. His father owned a brewery. Sperrle joined the Imperial German Army in 1903 as an officer cadet. He was assigned to an infantry regiment.

In 1912, he became a Leutnant (Second Lieutenant). By October 1913, he was promoted to Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant). When World War I started, Sperrle was training as an artillery spotter for the German Army Air Service. He became a Captain in November 1914. Sperrle was known for his strong record in aerial reconnaissance.

He first served as an observer, then trained as a pilot. He commanded several flying units. After being injured in a plane crash, he moved to an air observer school. When the war ended, he was in charge of flying units attached to the German 7th Army. For his service, he received the House Order of Hohenzollern.

Between the World Wars

After World War I, Sperrle joined the Freikorps, which were volunteer military units. He then joined the Reichswehr, the German army during the Weimar Republic. He commanded aviation units and fought near the border with Poland in 1919.

Sperrle helped study Germany's war experiences for the air service. He worked on the air staff in Stuttgart from 1919 to 1923. He also traveled to a secret German air base in Lipetsk, Soviet Union. There, German pilots were secretly trained between 1924 and 1932. Sperrle was a senior director at this base.

In 1927, Sperrle became head of the air staff at the Weapons and Troop Office. He was chosen for his technical skills and combat experience. He pushed for a separate air force. In 1929, the term "Luftwaffe" was first used for an embryonic air headquarters.

Sperrle was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1931 and to Colonel in 1933. After Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party took power, Hermann Göring created the Reich Air Ministry. Sperrle was given command of the First Air Division. He was responsible for coordinating air support for the army.

Sperrle was critical of some early German aircraft designs. He worked with other officers to improve aircraft production. They decided to use the Junkers Ju 52 as a temporary solution while newer planes like the Dornier Do 23, Junkers Ju 86, and Heinkel He 111 were developed.

On March 1, 1935, Göring officially announced the existence of the Luftwaffe. Sperrle was transferred to the Reich Air Ministry. He commanded Air District II and then Air District V in Munich. He was promoted to Brigadier General in October 1935.

Leading the Condor Legion in Spain

Sperrle became the first commander of the Condor Legion in November 1936. This was a group of German airmen sent to support General Franco and his Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War. Sperrle was in charge of all German forces in Spain until October 1937.

The Legion grew to 6,000 men by January 1937. German volunteers were rotated, allowing many to gain combat experience. Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen became Sperrle's chief of staff. They worked well together, advising Franco on how to use air power effectively. They believed German support should be limited.

Sperrle arrived in Spain in November 1936. His first mission was to airlift 20,000 men of the African Army. These experienced soldiers became a strong core for Franco's forces.

Spanish Civil War Battles

Sperrle started the war with 120 aircraft. For the first four months, the German aviators struggled. They lost 20% of their strength trying to capture Madrid in 1936. Soviet-designed fighter aircraft used by the Republican forces gained air superiority. Bombing raids against cities like Cartagena and Alicante failed. Sperrle personally led an attack on the Republican Navy at Cartagena, but most ships escaped.

Attacks on Madrid also failed, causing many civilian casualties. The Legion's bombers temporarily stopped daylight bombing. Sperrle's airmen then focused on attacking key points around Madrid. Pilots faced challenges flying in the mountains. Morale was also affected by poor living conditions and illness.

The German air force needed better fighter aircraft. The Heinkel He 51 was not good enough. Sperrle asked Berlin for modern planes. In January 1937, the Legion began receiving Dornier Do 17, Heinkel He 111, Junkers Ju 86 bombers, and Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters. Sperrle was promoted to Major General on April 1, 1937.

In the summer of 1937, the Nationalists aimed to destroy the Republican army in the Bay of Biscay area. Sperrle moved his headquarters to Vitoria. The Biscay Campaign began on March 31 with the Bombing of Durango. Sperrle protested to the Nationalists about the "waste of resources" when bombers hit the town instead of military targets.

Later, Sperrle's staff planned to bomb the Rentaria Bridge in Guernica. The town was an important transport hub for Republican forces. On April 26, 1937, 43 bombers dropped 50 tons of bombs on the town. This attack has been very controversial. While it was not meant to target civilians, about 300 Spanish people died. The attack did prevent Republican forces from moving heavy equipment across the bridge. Sperrle was not punished for the Guernica bombing.

The Condor Legion helped the Nationalists win the Battle of Bilbao. They also played a big role in defeating a Republican attack in the Battle of Brunete. By using fighter escorts and attacking airfields, the Nationalists gained air superiority. Sperrle's men helped defeat infantry and tanks. From then on, the Legion usually had control of the air.

In August and September 1937, Sperrle's Legion helped Franco win the Battle of Santander. They had only 68 aircraft. The Republicans lost many men. The Germans then focused on the Asturias Offensive, which ended the War in the North. Sperrle lost 12 aircraft and 22 men. The bombing was effective, causing heavy losses for Republican infantry.

Sperrle left Spain and returned to Germany on October 30, 1937. He was promoted to General of the Aviators on November 1, 1937.

Intimidation Tactics: Austria and Czechoslovakia

On February 1, 1938, Sperrle was given command of Luftwaffe Group 3, which later became Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet 3). He commanded this air fleet for the rest of his military career.

Hitler used Sperrle to intimidate smaller countries with the Luftwaffe's reputation. In February 1938, Hitler invited Sperrle to a meeting about Anschluss, the Nazi takeover of Austria. Sperrle's air fleet was mobilized for an invasion. His airmen dropped leaflets over Vienna. His combat units moved to airfields around Linz and Vienna during the invasion.

In April 1938, Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 had a fighter wing, two bomber wings, and a dive-bomber wing. His air fleet was used to threaten the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha. The goal was to force Czechoslovakia to accept Nazi rule. Sperrle had 650 aircraft. The Munich Agreement prevented war, and Sperrle's forces landed at Aš airfield when Germany annexed the Sudetenland in October 1938.

In March 1939, Hitler decided to take over all of Czechoslovakia. He again used the threat of air power. Hitler told Hácha that half of Prague could be destroyed in two hours. Sperrle was asked to talk about the Luftwaffe to intimidate the Czech president. Hácha reportedly fainted. He then ordered the Czechoslovakian Army not to resist. Sperrle's Air Fleet 3, with 500–650 aircraft, carried out the aerial part of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.

World War II Operations

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 stayed in western Germany to guard German airspace. It did not participate in the invasion of Poland. His air fleet was much smaller at this time.

Sperrle was known for his love of good food. His private transport plane even had a refrigerator for his wines. He was seen as reliable and tough. Sperrle wanted his air fleet to be more aggressive. He was allowed to conduct long-range reconnaissance missions. He lost some aircraft but got good information.

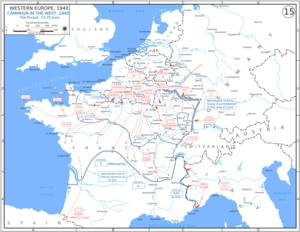

Battle of France

In the spring of 1940, Air Fleet 3 was greatly strengthened. Sperrle's headquarters was in Bad Orb. He had 1,788 aircraft, with 1,272 ready for operations. The French Air Force had fewer planes.

The Battle of France began on May 10, 1940. Sperrle's air fleet supported German ground forces. His initial attacks on Allied airfields were not very effective. However, his men claimed to have destroyed many Allied aircraft. Sperrle's air fleet lost 39 aircraft on the first day.

On May 10, 1940, one of Sperrle's units accidentally bombed Freiburg, causing civilian casualties. The Nazis blamed the British and French for this mistake.

Sperrle's bombers helped create breakthroughs for the German army. His air corps commanders targeted railways and roads to stop French troop movements. They also bombed airfields. On May 13, Sperrle's air fleet supported the German breakthrough at Sedan. The bombing helped the ground forces cross the Meuse river. Sperrle's fighters also defended the captured bridges from Allied attacks.

As German forces advanced to the English Channel, Sperrle's units continued to attack railways. This prevented Allied forces from regrouping. The British left France on May 19. Sperrle's forces also supported the German 4th Army near Arras.

Sperrle and Albert Kesselring, another air fleet commander, did not agree with the order to halt during the Battle of Dunkirk. They believed air power alone could not defeat the trapped Allied forces. Sperrle's men attacked shipping around Dunkirk. Despite flying many missions, Sperrle and Kesselring failed to prevent the Dunkirk evacuation.

For the next phase of the campaign, Sperrle's air fleet was reorganized. He had about 1,000 aircraft. Sperrle had planned to bomb Paris, but the city was declared an open city before the attack could happen. His forces then supported the German army's advance southward. They bombed bridges over the Loire river. On June 17, German forces reached the Swiss border, completing the encirclement.

The campaign ended on June 25, 1940. Sperrle was promoted to Field Marshal in the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony.

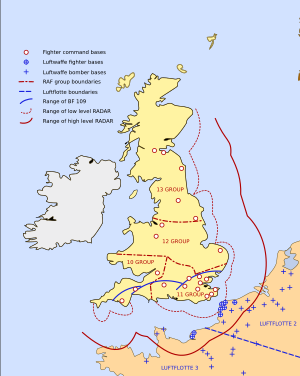

Battle of Britain

In July 1940, Winston Churchill's government refused Hitler's peace offers. Hitler decided to try and defeat Britain. The German air force planned Operation Eagle Attack to destroy RAF Fighter Command and gain air superiority.

Sperrle believed the RAF could be defeated. He wanted to attack ports and merchant ships. However, Göring overruled him. Sperrle and Kesselring underestimated the number of British fighter aircraft. German intelligence often provided incorrect information, which made German commanders overconfident.

The Luftwaffe was organized into three air fleets. Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 was based in western France. It was responsible for targets in the western and north-western parts of Britain. Sperrle's bombers were mainly used for night bombing.

Sperrle's first task was to attack Channel shipping during the Kanalkampf (Channel Battle). The goal was to draw out British fighters. His air fleet claimed to have sunk many ships, but these claims were too high. Sperrle became concerned about the loss of experienced officers.

On August 13, 1940, Sperrle's air fleet took part in the failed Operation Eagle Attack. That night, his bombers attacked a factory in Birmingham, but it was not successful. Göring was angry about the poor results. August 15, 1940, became known as "Black Thursday" for the Luftwaffe due to heavy losses.

On August 18, 1940, "The Hardest Day" was disastrous for Sperrle's air fleet. His intelligence was poor, and his units attacked British airfields that were not involved in the main air battle. Göring ordered Sperrle to bomb Liverpool. Three days later, Sperrle's air fleet was ordered to only conduct night attacks. His fighter units were transferred to Kesselring.

On the night of August 28, Air Fleet 3 attacked Liverpool. This was considered the first major night attack on the United Kingdom. Sperrle's air fleet sent many bombers to Liverpool and Birkenhead for three nights. The docks were not hit, and most damage was to suburban areas. Sperrle lost only a few crews because British night fighter defenses were weak.

By early September 1940, Sperrle had 350 bombers and about 100 fighters. He was skeptical about the reported losses of British Fighter Command. He had seen exaggerated claims before. He wanted to continue attacking the RAF and its bases.

However, Göring decided to attack London instead. Kesselring agreed, but Sperrle did not. Sperrle believed the British still had about 1,000 fighters, which was more accurate. Kesselring's view won out. This change in strategy relieved pressure on Fighter Command. On September 15, 1940, German aviators faced a prepared enemy and suffered heavy losses.

The Blitz

Bombing operations continued into October 1940, with more focus on industrial cities. The goal was to continue the war against Britain without an invasion. However, the damage to the British war economy and morale was minimal. More night operations were flown than day operations, which reduced German losses. Sperrle's command flew most of these missions.

Sperrle's air fleet received new units with special night navigation aids. He prepared for large-scale night operations. His air fleet helped start The Blitz, which began on September 7, 1940. That night, about 250 aircraft dropped many bombs on London.

In November 1940, Sperrle's airmen flew 4,525 bombing missions. His air fleet played a big role in the Birmingham and Coventry Blitz. Sperrle provided 304 of the 448 bombers for the Coventry attack. The goal was to disrupt production and make workers leave their homes. The city center was destroyed.

In November, Sperrle's bombers also attacked Southampton, destroying much of the city. They also bombed Birmingham and Liverpool. The bombing of Liverpool was not followed up the next night, allowing the city to recover.

In December 1940, Sperrle's air groups flew 2,750 bombing missions against British cities. Manchester was bombed in December 1940. Sheffield was also attacked. London remained a main target. On December 29, 1940, bombing caused what became known as the Second Great Fire of London. Sperrle's air fleet dropped many incendiary bombs that night.

In November 1940, Sperrle's bombers began the Bristol Blitz. Many bombs were dropped, killing 207 people and destroying thousands of houses. By January 1941, Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 was reorganized with more air corps and bomber wings.

In February 1941, bad weather limited bombing operations. Sperrle's bombers attacked Swansea, disrupting the railway. In March, bombing increased. Attacks on Cardiff caused some people to leave the city. Other cities like Liverpool, Glasgow, Bristol, London, Portsmouth, and Plymouth were also bombed.

In April 1941, the Midlands region of Britain was heavily bombed by Sperrle's air fleet. Birmingham and Coventry were attacked on consecutive nights. British ports like Plymouth, Glasgow, and Belfast were also bombed. April was the busiest month of the Blitz for Sperrle's air fleet in 1941.

In May 1941, Sperrle's air fleet made a navigation error and bombed Dublin, the capital of Ireland, instead of their targets in Liverpool. Units from his air fleet were also involved in the Hull and Nottingham Blitz. A final major attack was made on London on May 10. Sperrle's men carried out most of the night operations that month.

By early June 1941, most German bomber units moved east to prepare for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Air Defence and Later Offensives

After Kesselring's departure in mid-1941, Sperrle commanded all German air forces in France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Air Fleet 3 was responsible for defending German-occupied territory from RAF attacks, known as the Circus offensives. Sperrle had fewer fighter forces, only two wings, to cover a large coastal area.

From July to December 1941, Sperrle's fighters flew many missions and lost 93 aircraft. The number of German fighter aircraft in the west actually increased by September 1942.

In February 1942, Sperrle's air fleet helped the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Prinz Eugen escape from the French port of Brest in Operation Cerberus. This operation was a success for the Luftwaffe.

The Circus offensives in 1942 put pressure on Sperrle's air defenses. The largest air battle happened on August 19, 1942, during the Dieppe Raid. Sperrle's units won a significant victory, with the British losing many more aircraft than the Germans.

The Luftwaffe also launched offensive attacks in 1941 and 1942. Sperrle's air fleet carried out intense air attacks on Britain. The Baedeker Blitz was the largest air offensive against Britain in 1942. Hitler ordered Sperrle to bomb British cities that had cultural importance, as a form of "reprisal" for the bombing of Lübeck. These attacks aimed to affect civilian morale.

The Baedeker offensive began on April 23, 1942, with attacks on Exeter and Bath. York was also attacked. Sperrle's bombers flew at low altitudes to maximize damage. The offensive was halted on May 9. Sperrle's bombers suffered losses. Bombing operations continued against Birmingham and Canterbury. In 1942, Air Fleet 3 flew 2,400 night bomber missions against Britain.

On November 8, 1942, Allied forces landed in North Africa (Operation Torch). Hitler ordered Sperrle's forces to occupy the French-Mediterranean coast. Sperrle's command in the south supported the army and carried out reconnaissance. This gave Sperrle's fleet bases to attack shipping in the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1943, the Luftwaffe's offensive abilities declined. German bomber units flew fewer missions. In March 1943, Hitler ordered an officer named Dietrich Peltz to coordinate attacks on Britain. Peltz's command was part of Sperrle's air fleet. Peltz gathered 501 bombers for this task. German operations against Britain continued, but with fewer sorties and more losses.

Defence of the Reich and Normandy

In 1942, the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) began bombing targets in Belgium and France. In 1943, they extended their operations into Germany. Sperrle's fighter pilots bore the brunt of the defense. The air war escalated. Sperrle resisted attempts to centralize fighter forces, wanting to preserve his command.

On June 10, 1943, Air Fleet 3 had only one complete fighter wing. The Combined Bomber Offensive began, with round-the-clock bombing of German-occupied Europe. The goal was to destroy the Luftwaffe and gain air superiority before Operation Overlord (the D-Day landings). Sperrle's fighter forces suffered heavy losses.

Sperrle's headquarters remained in Paris. He had control of several fighter divisions. However, these divisions did not receive the reinforcements they needed. The Luftwaffe was forced into a battle of attrition it could not win.

In February 1944, Big Week targeted German and French bases. The German fighter force was severely weakened. By June 1944, Sperrle's air fleet was weak, with few ground-attack aircraft. He had at most 300 fighter aircraft on D-Day, while the Allies had 12,837 aircraft.

Another part of the air war was the night offensive against Germany by British Bomber Command. Hitler ordered Sperrle to use Peltz's bombers to strike back at Britain. This offensive was called Operation Steinbock and began in January 1944. Peltz was in charge, bypassing Sperrle. The offensive was weak and resulted in heavy German bomber losses. Sperrle had wanted to use his bombers to attack the invasion forces at their landing grounds in England, but Hitler and Göring rejected this idea.

Normandy and Dismissal

Allied intelligence knew the location and strength of German fighter units because they had cracked German codes. Allied attacks in May 1944 severely impacted Sperrle's air fleet. They destroyed German bases and forced Sperrle's air fleet to abandon efforts to prepare bases near the English Channel. Many German radar sites were also destroyed, blinding his fighter corps.

The Germans had planned to send reinforcements to Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 when the invasion happened. However, Allied intelligence knew about these plans. The Allied air offensive had already devastated German fighter bases and units.

On June 5, the eve of the Normandy Campaign, Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 had 600 aircraft of all types. However, only a small number were operational. German weather reports were wrong, so the invasion caught them by surprise.

The Allies had complete air superiority on June 6, 1944. They flew 14,000 missions to support the invasion. Sperrle's Air Fleet 3 barely reacted, launching less than 100 missions on the first day. Sperrle lost 39 aircraft.

Air Fleet 3 received 200 fighters from Germany within 36 hours, and another 100 by June 10. However, their effectiveness was reduced because air bases were constantly attacked. In the first two weeks of operations, Sperrle's air fleet lost nearly 75% of its aircraft. From June 6 to 30, the Germans lost 1,181 aircraft.

German fighters loaded with bombs suffered heavy losses and achieved little. Sperrle's air fleet also used new weapons like the Mistel and radio-guided missiles, but they had little effect on Allied shipping.

By July 9, Sperrle's units were ordered to save fuel. By August 1944, as the German army retreated from France, Sperrle's air fleet could only fly 250 missions to cover them.

Sperrle was dismissed from his post on August 23, 1944, just hours before Allied forces liberated Paris and overran his headquarters. Hitler blamed Sperrle for the collapse of the German front. Sperrle's command was downgraded to an air command.

By the time of his dismissal, Sperrle had reportedly lost faith in the German war effort. He was seen as lazy and enjoying the luxuries of occupied France. He was deemed unfit for a senior command and spent the rest of the war in the reserve. On May 1, 1945, Sperrle was captured by the British Army.

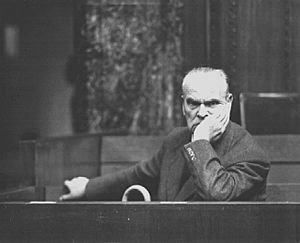

Later Life and Trial

After the war, Sperrle was charged with war crimes at the High Command Trial in Nuremberg. However, he was found not guilty. He was also acquitted in June 1949 after another hearing in Munich. The court found that Sperrle had never been a member of the Nazi Party. After the war, he lived a quiet life. He died in Munich on April 2, 1953, and was buried in Thaining, Bavaria.

Summary of Career

Awards

- Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd Class

- Military Merit Order (Württemberg)

- Military Merit Order (Bavaria) 4th Class with Swords

- Order from the Grand Duke of Baden Orden vom Zähringer Löwen (de) Knights Cross 2nd Class with Swords and oak leafs

- House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords

- The Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918

- Wehrmacht Long Service Award 1st to 4th Class

- Pilot/Observer Badge, In Gold with Diamonds]]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 17 May 1940 as General der Flieger and chief of Luftflotte 3

Dates of Rank

| 25 February 1904: | Fähnrich (Officer Candidate) |

| 18 October 1904: | Leutnant (Second Lieutenant) |

| 18 October 1912: | Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant) |

| 28 November 1914: | Hauptmann (Captain) |

| 1 October 1926: | Major |

| 1 February 1931: | Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) |

| 1 August 1933: | Oberst (Colonel) |

| 1 October 1935: | Generalmajor (Brigadier General) |

| 1 April 1937: | Generalleutnant (Major General) |

| 1 November 1937: | General der Flieger (General of the Aviators) |

| 19 July 1940: | Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hugo Sperrle para niños

In Spanish: Hugo Sperrle para niños