John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of St Vincent

|

|

|---|---|

The Earl of St Vincent, by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1795, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

|

|

| Born | 9 January 1735 Meaford Hall, Staffordshire |

| Died | 13 March 1823 (aged 88) Rochetts, Brentwood, Essex |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1749–1823 |

| Rank | Admiral of the Fleet |

| Commands held | HMS Porcupine HMS Scorpion HMS Albany HMS Gosport HMS Alarm HMS Kent HMS Foudroyant Leeward Islands Station Mediterranean Fleet Channel Fleet First Lord of the Admiralty |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath |

John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent (born January 9, 1735 – died March 13, 1823) was a very important admiral in the Royal Navy. He was also a Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom. Jervis served for a long time, from the mid-1700s into the early 1800s.

He was a leader during major conflicts like the Seven Years' War, the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary War, and the Napoleonic Wars. He is most famous for his big win at the Battle of Cape Saint Vincent in 1797. This victory earned him his noble titles.

Jervis was also a mentor to another famous admiral, Horatio Nelson. Even though Jervis was known for being very strict, his sailors liked him a lot. They even called him Old Jarvie.

People saw Jervis as a great organizer and someone who made the Navy better. As the leader of the Mediterranean Fleet from 1795 to 1799, he brought in tough rules to stop sailors from rebelling. He applied these rules to everyone, officers and sailors alike, which made him a bit controversial.

Later, as the First Lord of the Admiralty (the head of the Navy), he made many changes. These changes made the Navy more efficient, even if they weren't popular at the time. He introduced new ideas, like machines to make wooden blocks for ships at Portsmouth Royal Dockyard.

Jervis was known for being generous to officers who did well. But he was also quick and harsh with those he felt deserved punishment. A book called the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says he was important because he "organized victories" and created "well-equipped, highly efficient fleets." He also trained officers to be as professional and dedicated as he was.

Contents

John Jervis was born in Meaford Hall, Staffordshire, England, on January 9, 1735. He was the second son of Swynfen and Elizabeth Jervis. His father was a lawyer who worked for the Navy. Swynfen Jervis wanted John to become a lawyer too.

Young Jervis went to school at Burton Grammar School and then an academy in Greenwich, London.

When he was just thirteen, Jervis ran away to join the Navy in Woolwich, London. He soon went home because his family was very upset. But some important ladies, Lady Jane Hamilton and Lady Burlington, helped him. They convinced his family and introduced him to Admiral George Townshend. The Admiral agreed to take John on one of his ships.

On January 4, 1749, Jervis officially joined the Navy as an able seaman. He sailed on the 50-gun Gloucester to Jamaica. In the West Indies, he served on the sloop Ferret. There, he often fought against Spanish ships and privateers (ships allowed to attack enemy ships).

Jervis was later rated as a midshipman, a junior officer. He studied navigation and read a lot. Once, he got into debt in Jamaica because his father couldn't send him money. This experience taught him a valuable lesson about managing money.

He continued to serve on various ships, learning more about naval life. In 1755, he passed his lieutenant's exam. He became a lieutenant on the huge 100-gun Royal George.

By March 1756, he was on the 60-gun Nottingham. He helped Admiral Edward Boscawen try to stop French ships from reaching New France (Canada). The Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France had just begun.

In 1757, Jervis temporarily commanded HMS Experiment. He fought a French privateer in a battle that didn't have a clear winner. He then moved to other ships, always following his senior officer, Captain Charles Saunders.

Quebec and Becoming a Captain

In February 1759, Jervis's fleet sailed to North America to capture French lands in Canada. They went up the Saint Lawrence River to attack Quebec City.

On May 15, 1759, Jervis was made acting commander of the sloop HMS Porcupine. He greatly impressed General James Wolfe during the preparations for the famous Battle of the Plains of Abraham. His ship, Porcupine, helped lead the transport ships past Quebec to land troops upriver. General Wolfe and the famous explorer James Cook even boarded Porcupine to make sure the mission succeeded.

Because of his good work, Jervis was promoted to commander. He took command of HMS Scorpion. He returned to England but soon went back to North America.

In October 1760, he became a post-captain and commanded the 44-gun Gosport. A young midshipman named George Elphinstone, who later became Viscount Keith, served under him. In 1762, Gosport helped protect British trade ships from a French squadron.

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, Jervis was without a ship for several years. In 1769, he was given command of the 32-gun HMS Alarm. This was the first Royal Navy warship with a coppered hull, which protected it from worms and made it faster. He sailed to Genoa to deliver money to English merchants.

While in Genoa, two enslaved Turks escaped a Genoese ship and hid on Alarm. They were taken back, but Jervis protested strongly and got them returned to his ship. In 1770, Alarm ran aground near Marseilles, France. But with Jervis's efforts and help from the French, the ship was saved and repaired.

In 1771, Alarm brought the Duke of Gloucester, King George III's brother, to Italy. Jervis returned to England in 1772 and his ship was taken out of service.

Traveling Europe

From 1772 to 1775, Jervis traveled a lot. He went to France to study the language and learn about French life. He also visited Russia with Captain Samuel Barrington. They saw the Navy's dockyards and ships in Saint Petersburg and Kronstadt.

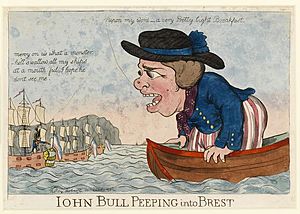

They continued their travels to Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. Jervis always took detailed notes on defenses, harbor maps, and safe places to anchor. They returned through the Netherlands, where Jervis again made many useful observations. He and Barrington then sailed along the English Channel coast, mapping harbors like Brest. These detailed maps later helped Jervis greatly when he commanded the Channel Fleet. He said that if he hadn't made those maps as a young captain, he wouldn't have been able to block Brest so well later on.

American War of Independence

When the American War of Independence began in 1775, Jervis was given command of HMS Kent. But the ship was found to be unfit. So, he was given command of HMS Foudroyant, a ship he had helped capture 17 years earlier.

At first, France secretly helped the Americans. But in 1778, France and America signed a treaty, and the war became bigger. Jervis spent the first few years patrolling the English Channel in Foudroyant.

First Battle of Ushant

In July 1778, Jervis was under the command of Admiral Augustus Keppel. The British fleet spotted the French fleet near Brest. On July 27, they fought in what became known as the First Battle of Ushant. The battle didn't have a clear winner. Afterward, Jervis strongly defended Admiral Keppel at his trial, helping him to be found innocent.

Relieving Gibraltar and Capturing Pégase

Jervis stayed with Foudroyant in the Channel Fleet. In 1780 and 1781, he helped Admiral Rodney and Admiral George Darby relieve Gibraltar, which was under siege.

On April 19, 1782, Jervis's squadron spotted a French convoy leaving Brest. Foudroyant chased and fought the French 74-gun Pégase. After more than an hour, Pégase surrendered. Jervis was wounded in the fight. For his bravery, he was made a Knight of the Bath in May 1782.

He was again at the relief of Gibraltar with Earl Howe's fleet in 1782. He also took part in the Battle of Cape Spartel, which was another indecisive battle. In December 1782, Jervis was promoted to commodore.

Marriage and Politics

During a time of peace, Jervis married his cousin, Martha Parker. He also became a MP for Launceston in 1783. Jervis supported Pitt's ideas for parliamentary reforms.

In 1784, Jervis became an MP for Great Yarmouth. He mostly spoke about naval matters in Parliament. In 1792, he suggested a plan to help older, retired sailors who were struggling financially.

In 1794, he left his political seat and did not run for office again.

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

Jervis was promoted to Vice-Admiral of the Blue. He was put in charge of the Leeward Islands. He led a joint military expedition with the army commander, Sir Charles Grey, who was a friend. Their goal was to capture French colonies and hurt France's trade.

Jervis used HMS Boyne as his main ship. His flag-captain was Captain George Grey, Sir Charles Grey's son. Their combined forces captured the French colonies of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint Lucia.

However, the French fought back and recaptured Guadeloupe in June 1794. Jervis and Grey tried to take it back but were pushed away by the strong French forces.

In November 1794, Admiral Benjamin Caldwell replaced Jervis. There were arguments about prize money (money from captured enemy ships). Despite this, Jervis and Grey received thanks from both Houses of Parliament for their service. On April 12, 1794, Jervis was promoted to vice-admiral of the white.

Leading the Mediterranean Fleet

Jervis was promoted to admiral of the blue on June 1, 1795. He was then put in charge of the Mediterranean Fleet. His ship, Boyne, had accidentally caught fire and exploded, so Jervis lost almost all his belongings.

Jervis took command of the Mediterranean fleet on HMS Victory. Among his officers were famous captains like Horatio Nelson and Cuthbert Collingwood.

Jervis began a close blockade of Toulon, a French port. Nelson helped the Austrian army along the Italian coast. But by September 1796, Britain's position in the Mediterranean became difficult. Napoleon had defeated Britain's Austrian allies. In October, Spain joined forces with the French.

Jervis had to pull his forces back to Gibraltar. He abandoned Corsica between September and November 1796.

Battle of Cape St. Vincent

A Spanish fleet of 24 large warships and seven frigates sailed from Toulon on February 1, 1797. Jervis's fleet of ten warships was patrolling off Cape Saint Vincent. Five more ships joined him. The Spanish admiral, José de Córdoba, was heading to Cadiz when the two fleets saw each other on February 14, 1797.

The British fleet had 15 warships against the Spanish 24. On the deck of Victory, Jervis and his flag captain, Robert Calder, counted the enemy ships. Jervis realized he was outnumbered almost two to one. He famously said, "Enough, sir, no more of that; the die is cast, and if there are fifty sail I will go through them."

During the battle, Nelson, commanding HMS Captain, bravely broke from the battle line. He managed to capture two enemy ships very quickly. Nelson and his crew boarded one ship, then crossed its deck to board and capture a second ship that had crashed into the first. This daring move was called "Nelson's patent bridge for boarding first-rates" by the public.

When the Spanish retreated, Jervis didn't chase them. Instead, he focused on repairing his ships and helping his crews. The British had 73 killed and 227 wounded.

Jervis didn't mention Nelson's amazing actions in his first report to the Admiralty. But he did mention Nelson in later reports. When his flag-captain, Sir Robert Calder, brought up Nelson's disobedience, Jervis replied, "It certainly was so, and if you ever commit such a breach of your orders, I will forgive you also."

Even though only four Spanish ships were captured, the Battle of Cape Saint Vincent was seen as a huge victory. It boosted the spirits of the British people and politicians, who were worried about a French invasion.

Both Jervis and Nelson were celebrated as heroes. Jervis was made a Baron and an Earl, becoming Earl St Vincent. He was given a pension of £3,000 a year for life. The City of London gave him a special gold box and a presentation sword. Nelson was also honored.

Jervis then continued his blockade of the Spanish fleet in Cadiz.

Mutiny and Discipline

In 1797, there was a lot of unhappiness among Royal Navy sailors. This led to major mutinies at Spithead and the Nore. Most of the Channel Fleet rebelled against their officers.

These mutinies were not very violent. Officers were put ashore, and the mutineers set up their own committees to control the ships. They demanded better pay, better treatment, and more time ashore. Other mutinies, like those on HMS Hermione, were more violent. Crews killed their officers and took their ships to enemy ports.

Jervis was known for his strict discipline. He created a new system to prevent mutiny in the Mediterranean fleet. He wrote new rules. For example, he separated sailors and marines, placing marines between the officers and the sailors. This created a barrier to prevent trouble.

Jervis also ordered marines to parade every morning with their weapons. He made sure his crews stayed active. He even ordered nightly bombardments of Cadiz to keep the men busy and to show the Spanish that the British fleet was still strong.

He kept ships isolated from each other to stop sailors from planning mutinies together. But Jervis also made sure his men were well cared for. When tobacco ran low, he bought more with his own money. He set up a post office on his flagship, HMS Ville de Paris, to make sure letters from home reached the sailors.

Jervis followed the Articles of War (Navy rules) very strictly. He treated officers and sailors with the same harsh discipline. For example, an officer who let his crew steal from a fishing boat was publicly stripped of his uniform. Jervis also ordered that the officer's head be shaved and that he clean the ship's toilets.

In another case, Jervis ordered two men tried for mutiny on a Saturday to be executed on Sunday. When an admiral objected to Sunday executions, Jervis demanded that admiral be removed. The Admiralty removed the objecting admiral. Nelson supported Jervis's decision.

But Jervis could also be very kind. Once, a sailor lost all his savings (prize money and back pay) when his bank notes got wet while he was swimming. Jervis heard about it and called the sailor forward. He praised the sailor's bravery in battle. Then, Jervis gave the surprised sailor £70 of his own money, saying, "but no more tears mind, no more tears Sir."

When Nelson returned to the Mediterranean, St Vincent was thrilled. He wrote to the First Lord of the Admiralty, saying Nelson's arrival gave him "new life." St Vincent sent Nelson to chase Napoleon, who was invading Egypt.

Rear-Admiral Sir John Orde, who was senior to Nelson, complained about Nelson being given command. Jervis sent Orde home. Orde tried to have Jervis put on trial, but the Navy Board refused.

Jervis also improved the dockyards and defenses of Gibraltar. He built large water tanks for fresh water and planned a new yard to resupply ships. After the Battle of the Nile, the dockyards, under Jervis's supervision, successfully repaired most of Nelson's fleet.

On February 14, 1799, St Vincent was made admiral of the white. He was getting older and his health was failing. He had to resign his command and return to England. He lived at Rochetts, in South Weald, Essex, with his wife.

Leading the Channel Fleet Again

As his health improved, Jervis was given command of the Channel Fleet. He said, "The King and the government require it and the discipline of the British Navy demands it."

He took command of the Channel fleet on April 26, 1800, on HMS Namur. He began a close blockade of Brest, a French port. He later moved to Ville de Paris and brought Sir Thomas Troubridge as his flag captain. He also had his personal doctor, Andrew Baird, with him.

Jervis's appointment was not popular with all officers. His strict reputation had followed him. He immediately ordered that officers and captains could not sleep ashore or travel far from their ships. One captain's wife reportedly toasted, "May his next glass of wine choke the wretch."

He also ordered that ships be repaired at sea whenever possible. He made Ushant the official meeting point for the fleet, instead of the traditional Torbay. Ships were not allowed to go to Spithead without his specific written orders. Jervis stayed with the fleet and earned respect for sharing their hardships.

His old maps of Brest, made with Barrington in 1775, helped the inshore squadron keep a very tight blockade. In one incident, French ships tried to leave Brest. Sir Edward Pellew chased them, but his rear admiral called him back, fearing his ship would run aground. The French escaped.

Jervis was very upset. He sailed his entire offshore squadron between the inshore squadron and the shore. This showed that the ships could have chased the French. He then suggested the rear admiral go home for some rest.

Jervis was also generous in the Channel. He hosted a dinner for 50 officers. He told them he had received a letter from an orphanage near Paddington in London. The orphanage needed money to support children of sailors who had died serving their country. Jervis asked each captain and lieutenant for money and added his own large donation. He gave the orphanage £1,000.

Jervis was excellent at managing the fleet's health. Based on Doctor Baird's advice, he brought in fresh vegetables and lemon juice to prevent illnesses like scurvy. The results were amazing. The hospital ship was sent home because it wasn't needed. In November 1800, there were only 16 hospital cases among 23,000 men. Jervis called Doctor Baird "the most valuable man in the Navy."

In 1801, Jervis famously said, "I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea." This meant he believed the French would not be able to cross the sea to invade Britain because of the strong British Navy. Later in 1801, Jervis was replaced by Admiral William Cornwallis. The new Prime Minister, Henry Addington, promoted St Vincent to First Lord of the Admiralty.

First Lord of the Admiralty

As First Lord, St Vincent wanted to fix the corruption in the Navy, especially in the Royal Dockyards. He believed these problems were hurting the Navy's efforts.

Investigating Corruption

After a peace treaty with France in 1802, St Vincent ordered an investigation into fraud and corruption in the Royal Dockyards. He quickly found that the investigations were not working well. He ordered all records to be sealed and planned to inspect the yards himself.

The investigation began seriously in 1802. St Vincent found clear abuses. Some people were paid for work they didn't do. Others were listed as workers ashore and also as sailors getting paid on ships. Work was charged multiple times. In one yard, an entire department seemed to be made up of people who were too old, sick, or disabled to work.

St Vincent realized that small officials were part of a much bigger problem. He asked the government to create a special group to question people under oath. The government allowed this, but suspects could refuse to answer questions that might get them into trouble. This made the investigation less effective.

The Commission of Inquiry produced twelve reports. They found that valuable British wood was rotting because it wasn't being used. Ships were rotting because they were built with poor materials.

Making Reforms

One important change St Vincent made was introducing block making machinery at the Navy yard in Portsmouth. These machines were designed by Marc Isambard Brunel and Samuel Bentham. By 1808, 45 machines were making 130,000 pulley blocks each year. This meant that only a few unskilled men could do the work of 100 skilled blockmakers. The machines paid for themselves in three years. This made the Navy self-sufficient in making these important parts.

This self-sufficiency also helped reduce corruption. It stopped bad contractors from making poor quality goods that put sailors' lives at risk. It also reduced bribes to officials who awarded contracts. The buildings that housed these machines are still part of the Historic Portsmouth Dockyard today.

As First Lord, St Vincent also decided to build a breakwater in Plymouth. He hired a civil engineer, John Rennie, to design it. Work didn't start until 1811, but St Vincent is given credit for pushing for its construction.

St Vincent also spoke to the King about the important role of marines in the Navy. He suggested adding the word "Royal" to their name, leading to the creation of the Royal Marines.

During his time, workers in the Royal dockyards asked for more pay. St Vincent fired the leaders of the strike. But he eventually agreed to a small temporary payment for bread while prices were high.

St Vincent looked at every part of the Navy. He tried to disband the Sea Fencibles, civilian groups of merchant seamen who used their own boats. He thought they were not very useful. Doctor Baird, St Vincent's personal doctor, was appointed to inspect all Navy hospitals.

Promotions and Challenges

As First Lord, St Vincent received many letters from officers and their families asking for promotions. It was common practice to use influence to get a good position. But jobs were scarce because of the peace with France. St Vincent had to reject many requests.

St Vincent had publicly stated that officers would be promoted based on their achievements, not on their social or political influence. He often wrote strong letters to those who tried to use their influence. For example, he told the Earl of Portsmouth that someone who stayed home during the war didn't deserve promotion as much as someone who risked their life.

However, he was kinder to others. To a lady of no high rank, he wrote that he admired her for trying to help her brother get promoted.

A famous example involves Commander Lord Cochrane. Cochrane captured a Spanish frigate with a much smaller ship. This amazing feat usually earned a promotion. But the letter about his victory was delayed. Cochrane was later captured by the French and faced a trial for losing his ship (a common formality). He could only be promoted after being cleared.

Cochrane believed St Vincent deliberately held back his promotion. He had many powerful friends who kept asking for his promotion. This might have annoyed Jervis.

Leaving the Admiralty

St Vincent's detailed investigation into corruption made him very unpopular. Many powerful men were involved in the schemes. The inquiry even led to the trial of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, a very powerful politician. Melville was accused of misusing public money and resigned. Although he was later found not guilty, St Vincent had made an enemy of Prime Minister William Pitt.

Pitt used the unpopularity of the naval reforms to attack St Vincent. St Vincent left his office on May 14, 1804, when Pitt became Prime Minister again. In 1806, Lord Howick and Charles James Fox praised St Vincent in Parliament for his hard work in naval reform.

On May 14, 1806, a Member of Parliament tried to blame St Vincent for neglecting ship building and leaving the Navy in a worse state. But this idea was rejected. Instead, Parliament voted to thank Earl St Vincent for his excellent work in the Navy.

Later Commands and Retirement

On November 9, 1805, St Vincent was promoted to admiral of the red. He took command of the Channel Fleet again on the 110-gun HMS Hibernia. He spent much of his time at a rented house in Rame. He brought back his strict but effective orders, which were still unpopular with some.

In 1806, he briefly gave command to his second-in-command to travel to Portugal. He was ordered to help the Portuguese royal family escape to Brazil if Portugal was invaded. The invasion was delayed, and St Vincent was called back to the Channel Fleet.

St Vincent always tried to promote officers based on their skill, not their family connections. He was frustrated that young nobles and sons of MPs often got promotions over more deserving officers. He told the King that the Navy was "overrun by the younger branches of nobility." He said he would rather promote the son of a deserving old officer than any noble.

St Vincent had poor health for a long time. A change in government led to his retirement on April 24, 1807.

Final Years and Legacy

In his retirement, he rarely attended the House of Lords. He gave a lot of money to charities and individuals. He donated £500 to those wounded in the Battle of Waterloo and £300 to help people starving in Ireland. He also gave £100 to build a Jewish chapel in Whitechapel, London.

In 1807, St Vincent spoke against a law to end the slave trade. He argued that if Britain banned it, other countries would continue it, and Britain would lose money.

In 1816, his wife Martha died. They had no children. In 1818–1819, St Vincent went to France to improve his health. When he arrived in Toulon, a French admiral said he was "as much the father of the French as of the English Navy."

Further Honors

In 1800, St Vincent was made an honorary lieutenant-general of Marines. In 1814, he was promoted to general. These were honorary titles with no official duties.

In 1801, St Vincent was given the title Viscount St Vincent. Since he had no children, this title later passed to his nephew, Edward Jervis Ricketts. In 1806, he became one of the 31 elder brothers of Trinity House, an important organization for maritime safety.

In 1809, King John VI of Portugal gave him the Royal Portuguese Military Order of the Tower and Sword. This honored his role in helping the Portuguese Royal Family escape to Brazil when Napoleon invaded Portugal.

In May 1814, he was promoted to acting admiral of the fleet. He was confirmed as Admiral of the Fleet on July 19, 1821. King George IV sent him a gold-topped baton, a symbol of this high office. The baton is now at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

On January 2, 1815, he was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath, the highest rank in that order.

Death and Memorial

St Vincent died on March 13, 1823. Because he had no children, his noble titles (Barony of Jervis and Earldom of St Vincent) ended. His nephew, Edward Jervis Ricketts, became the 2nd Viscount St Vincent and changed his last name to Jervis to honor his uncle. St Vincent was buried in the family tomb in Stone, Staffordshire, as he wished. A monument was built for him in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London.

Legacy

Several ships and shore bases have been named HMS St Vincent in his honor or after his famous battle. HMS St Vincent, launched in 1910, was the first of her class of battleships. The St Vincent-class battleship class included HMS Collingwood and HMS Vanguard.

Jervis, a destroyer launched before World War II, was named after him. HMS Jervis served throughout the war and was known as a lucky ship because she never lost a man to enemy fire. HMS Jervis Bay, an armed merchant ship, was indirectly named after him. She was sunk heroically in 1940 by the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer.

Jervis is also remembered in schools. There is a boarding house named Saint Vincent at the Royal Hospital School in Holbrook, Suffolk. St Vincent College in Gosport, England, is named after his most famous battle.

Many places around the world are named after him. These include Cape Jervis and Gulf St Vincent in South Australia, and Jervis Bay in New South Wales, Australia. The town of Vincentia and Jervis Bay National Park are also named for him. Jervis Inlet in British Columbia, Canada, also bears his name.

Jervis appears as a character in two Horatio Hornblower novels, Hornblower and the Atropos and Lord Hornblower.

Images for kids

-

Howe's Relief of Gibraltar 1782

by Richard Paton -

Capture of Fort Louis, Martinique 20 March 1794

by William Anderson -

Plan of the fleet deployment during the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, 14 February 1797

by Alfred Thayer Mahan

See also

- Letters of Admiral of the fleet, the John Jervis, Earl of St. Vincent whilst the first lord of the Admiralty, 1801–1804, edited by David Bonner-Smith. Publications of the Navy Records Society, vols. 55, 61 ([London]: Printed for the Navy Records Society, 1922–27).

In Spanish: John Jervis para niños

In Spanish: John Jervis para niños